The rise and fall of peer review

Why the greatest scientific experiment in history failed, and why that's a great thing

For the last 60 years or so, science has been running an experiment on itself. The experimental design wasn’t great; there was no randomization and no control group. Nobody was in charge, exactly, and nobody was really taking consistent measurements. And yet it was the most massive experiment ever run, and it included every scientist on Earth.

Most of those folks didn’t even realize they were in an experiment. Many of them, including me, weren’t born when the experiment started. If we had noticed what was going on, maybe we would have demanded a basic level of scientific rigor. Maybe nobody objected because the hypothesis seemed so obviously true: science will be better off if we have someone check every paper and reject the ones that don’t pass muster. They called it “peer review.”

This was a massive change. From antiquity to modernity, scientists wrote letters and circulated monographs, and the main barriers stopping them from communicating their findings were the cost of paper, postage, or a printing press, or on rare occasions, the cost of a visit from the Catholic Church. Scientific journals appeared in the 1600s, but they operated more like magazines or newsletters, and their processes of picking articles ranged from “we print whatever we get” to “the editor asks his friend what he thinks” to “the whole society votes.” Sometimes journals couldn’t get enough papers to publish, so editors had to go around begging their friends to submit manuscripts, or fill the space themselves. Scientific publishing remained a hodgepodge for centuries.

(Only one of Einstein’s papers was ever peer-reviewed, by the way, and he was so surprised and upset that he published his paper in a different journal instead.)

That all changed after World War II. Governments poured funding into research, and they convened “peer reviewers” to ensure they weren’t wasting their money on foolish proposals. That funding turned into a deluge of papers, and journals that previously struggled to fill their pages now struggled to pick which articles to print. Reviewing papers before publication, which was “quite rare” until the 1960s, became much more common. Then it became universal.

Now pretty much every journal uses outside experts to vet papers, and papers that don’t please reviewers get rejected. You can still write to your friends about your findings, but hiring committees and grant agencies act as if the only science that exists is the stuff published in peer-reviewed journals. This is the grand experiment we’ve been running for six decades.

The results are in. It failed.

A WHOLE LOTTA MONEY FOR NOTHIN’

Peer review was a huge, expensive intervention. By one estimate, scientists collectively spend 15,000 years reviewing papers every year. It can take months or years for a paper to wind its way through the review system, which is a big chunk of time when people are trying to do things like cure cancer and stop climate change. And universities fork over millions for access to peer-reviewed journals, even though much of the research is taxpayer-funded, and none of that money goes to the authors or the reviewers.

Huge interventions should have huge effects. If you drop $100 million on a school system, for instance, hopefully it will be clear in the end that you made students better off. If you show up a few years later and you’re like, “hey so how did my $100 million help this school system” and everybody’s like “uhh well we’re not sure it actually did anything and also we’re all really mad at you now,” you’d be really upset and embarrassed. Similarly, if peer review improved science, that should be pretty obvious, and we should be pretty upset and embarrassed if it didn’t.

It didn’t. In all sorts of different fields, research productivity has been flat or declining for decades, and peer review doesn’t seem to have changed that trend. New ideas are failing to displace older ones. Many peer-reviewed findings don’t replicate, and most of them may be straight-up false. When you ask scientists to rate 20th century discoveries in physics, medicine, and chemistry that won Nobel Prizes, they say the ones that came out before peer review are just as good or even better than the ones that came out afterward. In fact, you can’t even ask them to rate the Nobel Prize-winning discoveries from the 1990s and 2000s because there aren’t enough of them.

Of course, a lot of other stuff has changed since World War II. We did a terrible job running this experiment, so it’s all confounded. All we can say from these big trends is that we have no idea whether peer review helped, it might have hurt, it cost a ton, and the current state of the scientific literature is pretty abysmal. In this biz, we call this a total flop.

POSTMORTEM

What went wrong?

Here’s a simple question: does peer review actually do the thing it’s supposed to do? Does it catch bad research and prevent it from being published?

It doesn’t. Scientists have run studies where they deliberately add errors to papers, send them out to reviewers, and simply count how many errors the reviewers catch. Reviewers are pretty awful at this. In this study reviewers caught 30% of the major flaws, in this study they caught 25%, and in this study they caught 29%. These were critical issues, like “the paper claims to be a randomized controlled trial but it isn’t” and “when you look at the graphs, it’s pretty clear there’s no effect” and “the authors draw conclusions that are totally unsupported by the data.” Reviewers mostly didn’t notice.

In fact, we’ve got knock-down, real-world data that peer review doesn’t work: fraudulent papers get published all the time. If reviewers were doing their job, we’d hear lots of stories like “Professor Cornelius von Fraud was fired today after trying to submit a fake paper to a scientific journal.” But we never hear stories like that. Instead, pretty much every story about fraud begins with the paper passing review and being published. Only later does some good Samaritan—often someone in the author’s own lab!—notice something weird and decide to investigate. That’s what happened with this this paper about dishonesty that clearly has fake data (ironic), these guys who have published dozens or even hundreds of fraudulent papers, and this debacle:

Why don’t reviewers catch basic errors and blatant fraud? One reason is that they almost never look at the data behind the papers they review, which is exactly where the errors and fraud are most likely to be. In fact, most journals don’t require you to make your data public at all. You’re supposed to provide them “on request,” but most people don’t. That’s how we’ve ended up in sitcom-esque situations like ~20% of genetics papers having totally useless data because Excel autocorrected the names of genes into months and years.

(When one editor started asking authors to add their raw data after they submitted a paper to his journal, half of them declined and retracted their submissions. This suggests, in the editor’s words, “a possibility that the raw data did not exist from the beginning.”)

The invention of peer review may have even encouraged bad research. If you try to publish a paper showing that, say, watching puppy videos makes people donate more to charity, and Reviewer 2 says “I will only be impressed if this works for cat videos as well,” you are under extreme pressure to make a cat video study work. Maybe you fudge the numbers a bit, or toss out a few outliers, or test a bunch of cat videos until you find one that works and then you never mention the ones that didn’t. 🎶 Do a little fraud // get a paper published // get down tonight 🎶

PEER REVIEW, WE HARDLY TOOK YE SERIOUSLY

Here’s another way that we can test whether peer review worked: did it actually earn scientists' trust?

Scientists often say they take peer review very seriously. But people say lots of things they don’t mean, like “It’s great to e-meet you” and “I’ll never leave you, Adam.” If you look at what scientists actually do, it’s clear they don’t think peer review really matters.

First: if scientists cared a lot about peer review, when their papers got reviewed and rejected, they would listen to the feedback, do more experiments, rewrite the paper, etc. Instead, they usually just submit the same paper to another journal. This was one of the first things I learned as a young psychologist, when my undergrad advisor explained there is a “big stochastic element” in publishing (translation: “it’s random, dude”). If the first journal didn’t work out, we’d try the next one. Publishing is like winning the lottery, she told me, and the way to win is to keep stuffing the box with tickets. When very serious and successful scientists proclaim that your supposed system of scientific fact-checking is no better than chance, that’s pretty dismal.

Second: once a paper gets published, we shred the reviews. A few journals publish reviews; most don't. Nobody cares to find out what the reviewers said or how the authors edited their paper in response, which suggests that nobody thinks the reviews actually mattered in the first place.

And third: scientists take unreviewed work seriously without thinking twice. We read “preprints” and working papers and blog posts, none of which have been published in peer-reviewed journals. We use data from Pew and Gallup and the government, also unreviewed. We go to conferences where people give talks about unvetted projects, and we do not turn to each other and say, “So interesting! I can’t wait for it to be peer reviewed so I can find out if it’s true.”

Instead, scientists tacitly agree that peer review adds nothing, and they make up their minds about scientific work by looking at the methods and results. Sometimes people say the quiet part loud, like Nobel laureate Sydney Brenner:

I don’t believe in peer review because I think it’s very distorted and as I’ve said, it’s simply a regression to the mean. I think peer review is hindering science. In fact, I think it has become a completely corrupt system.

CAN WE FIX IT? NO WE CAN'T

I used to think about all the ways we could improve peer review. Reviewers should look at the data! Journals should make sure that papers aren’t fraudulent!

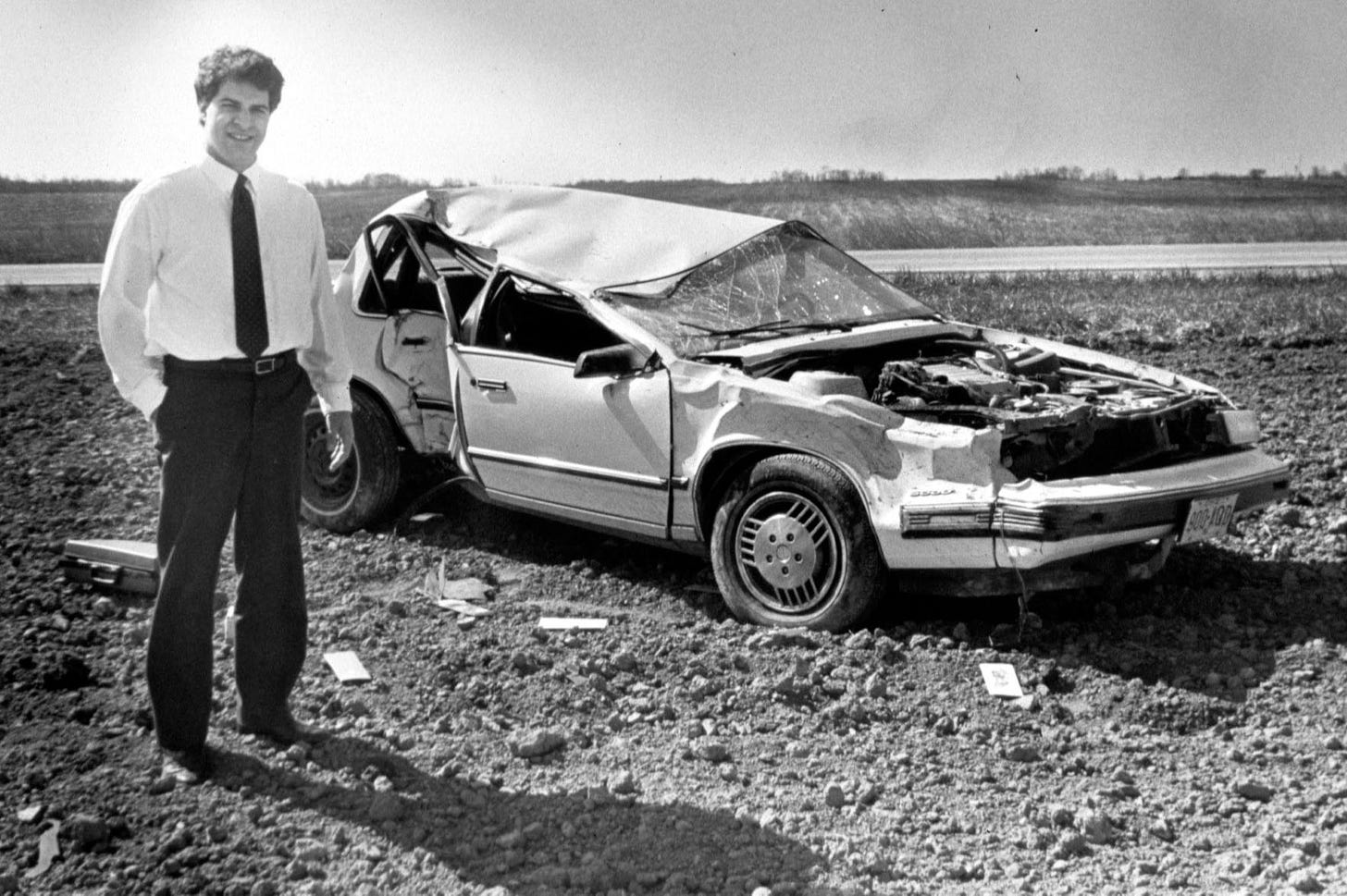

It’s easy to imagine how things could be better—my friend Ethan and I wrote a whole paper on it—but that doesn’t mean it’s easy to make things better. My complaints about peer review were a bit like looking at the ~35,000 Americans who die in car crashes every year and saying “people shouldn’t crash their cars so much.” Okay, but how?

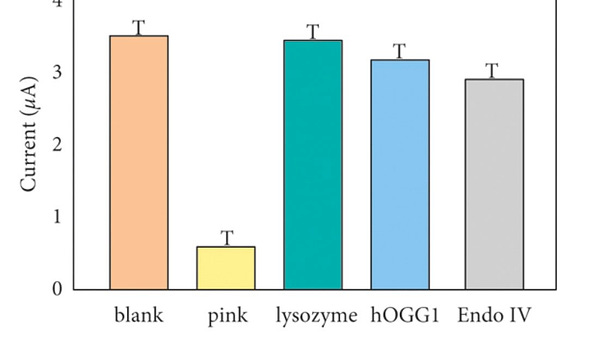

Lack of effort isn’t the problem: remember that our current system requires 15,000 years of labor every year, and it still does a really crappy job. Paying peer reviewers doesn’t seem to make them any better. Neither does training them. Maybe we can fix some things on the margins, but remember that right now we’re publishing papers that use capital T’s instead of error bars, so we’ve got a long, long way to go.

What if we made peer review way stricter? That might sound great, but it would make lots of other problems with peer review way worse.

For example, you used to be able to write a scientific paper with style. Now, in order to please reviewers, you have to write it like a legal contract. Papers used to begin like, “Help! A mysterious number is persecuting me,” and now they begin like, “Humans have been said, at various times and places, to exist, and even to have several qualities, or dimensions, or things that are true about them, but of course this needs further study (Smergdorf & Blugensnout, 1978; Stikkiwikket, 2002; von Fraud et al., 2018b)”.

This blows. And as a result, nobody actually reads these papers. Some of them are like 100 pages long with another 200 pages of supplemental information, and all of it is written like it hates you and wants you to stop reading immediately. Recently, a friend asked me when I last read a paper from beginning to end; I couldn’t remember, and neither could he. “Whenever someone tells me they loved my paper,” he said, “I say thank you, even though I know they didn’t read it.” Stricter peer review would mean even more boring papers, which means even fewer people would read them.

Making peer review harsher would also exacerbate the worst problem of all: just knowing that your ideas won’t count for anything unless peer reviewers like them makes you worse at thinking. It’s like being a teenager again: before you do anything, you ask yourself, “BUT WILL PEOPLE THINK I’M COOL?” When getting and keeping a job depends on producing popular ideas, you can get very good at thought-policing yourself into never entertaining anything weird or unpopular at all. That means we end up with fewer revolutionary ideas, and unless you think everything’s pretty much perfect right now, we need revolutionary ideas real bad.

On the off chance you do figure out a way to improve peer review without also making it worse, you can try convincing the nearly 30,000 scientific journals in existence to apply your magical method to the ~4.7 million articles they publish every year. Good luck!

PEER REVIEW IS WORSE THAN NOTHING; OR, WHY IT AIN’T ENOUGH TO SNIFF THE BEEF

Peer review doesn’t work and there’s probably no way to fix it. But a little bit of vetting is better than none at all, right?

I say: no way.

Imagine you discover that the Food and Drug Administration’s method of “inspecting” beef is just sending some guy (“Gary”) around to sniff the beef and say whether it smells okay or not, and the beef that passes the sniff test gets a sticker that says “INSPECTED BY THE FDA.” You’d be pretty angry. Yes, Gary may find a few batches of bad beef, but obviously he’s going to miss most of the dangerous meat. This extremely bad system is worse than nothing because it fools people into thinking they’re safe when they’re not.

That’s what our current system of peer review does, and it’s dangerous. That debunked theory about vaccines causing autism comes from a peer-reviewed paper in one of the most prestigious journals in the world, and it stayed there for twelve years before it was retracted. How many kids haven’t gotten their shots because one rotten paper made it through peer review and got stamped with the scientific seal of approval?

If you want to sell a bottle of vitamin C pills in America, you have to include a disclaimer that says none of the claims on the bottle have been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Maybe journals should stamp a similar statement on every paper: “NOBODY HAS REALLY CHECKED WHETHER THIS PAPER IS TRUE OR NOT. IT MIGHT BE MADE UP, FOR ALL WE KNOW.” That would at least give people the appropriate level of confidence.

SCIENCE MUST BE FREE

Why did peer review seem so reasonable in the first place?

I think we had the wrong model of how science works. We treated science like it’s a weak-link problem where progress depends on the quality of our worst work. If you believe in weak-link science, you think it’s very important to stamp out untrue ideas—ideally, prevent them from being published in the first place. You don’t mind if you whack a few good ideas in the process, because it’s so important to bury the bad stuff.

But science is a strong-link problem: progress depends on the quality of our best work. Better ideas don’t always triumph immediately, but they do triumph eventually, because they’re more useful. You can’t land on the moon using Aristotle’s physics, you can’t turn mud into frogs using spontaneous generation, and you can’t build bombs out of phlogiston. Newton’s laws of physics stuck around; his recipe for the Philosopher’s Stone didn’t. We didn’t need a scientific establishment to smother the wrong ideas. We needed it to let new ideas challenge old ones, and time did the rest.

If you’ve got weak-link worries, I totally get it. If we let people say whatever they want, they will sometimes say untrue things, and that sounds scary. But we don’t actually prevent people from saying untrue things right now; we just pretend to. In fact, right now we occasionally bless untrue things with big stickers that say “INSPECTED BY A FANCY JOURNAL,” and those stickers are very hard to get off. That’s way scarier.

Weak-link thinking makes scientific censorship seem reasonable, but all censorship does is make old ideas harder to defeat. Remember that it used to be obviously true that the Earth is the center of the universe, and if scientific journals had existed in Copernicus’ time, geocentrist reviewers would have rejected his paper and patted themselves on the back for preventing the spread of misinformation. Eugenics used to be hot stuff in science—do you think a bunch of racists would give the green light to a paper showing that Black people are just as smart as white people? Or any paper at all by a Black author? (And if you think that’s ancient history: this dynamic is still playing out today.) We still don’t understand basic truths about the universe, and many ideas we believe today will one day be debunked. Peer review, like every form of censorship, merely slows down truth.

HOORAY WE FAILED

Nobody was in charge of our peer review experiment, which means nobody has the responsibility of saying when it’s over. Seeing no one else, I guess I’ll do it:

We’re done, everybody! Champagne all around! Great work, and congratulations. We tried peer review and it didn’t work.

Honesty, I’m so relieved. That system sucked! Waiting months just to hear that an editor didn’t think your paper deserved to be reviewed? Reading long walls of text from reviewers who for some reason thought your paper was the source of all evil in the universe? Spending a whole day emailing a journal begging them to let you use the word “years” instead of always abbreviating it to “y” for no reason (this literally happened to me)? We never have to do any of that ever again.

I know we all might be a little disappointed we wasted so much time, but there's no shame in a failed experiment. Yes, we should have taken peer review for a test run before we made it universal. But that’s okay—it seemed like a good idea at the time, and now we know it wasn’t. That’s science! It will always be important for scientists to comment on each other’s ideas, of course. It’s just this particular way of doing it that didn’t work.

What should we do now? Well, last month I published a paper, by which I mean I uploaded a PDF to the internet. I wrote it in normal language so anyone could understand it. I held nothing back—I even admitted that I forgot why I ran one of the studies. I put jokes in it because nobody could tell me not to. I uploaded all the materials, data, and code where everybody could see them. I figured I’d look like a total dummy and nobody would pay any attention, but at least I was having fun and doing what I thought was right.

Then, before I even told anyone about the paper, thousands of people found it, commented on it, and retweeted it.

Total strangers emailed me thoughtful reviews. Tenured professors sent me ideas. NPR asked for an interview. The paper now has more views than the last peer-reviewed paper I published, which was in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. And I have a hunch far more people read this new paper all the way to the end, because the final few paragraphs got a lot of comments in particular. So I dunno, I guess that seems like a good way of doing it?

I don’t know what the future of science looks like. Maybe we’ll make interactive papers in the metaverse or we’ll download datasets into our heads or whisper our findings to each other on the dance floor of techno-raves. Whatever it is, it’ll be a lot better than what we’ve been doing for the past sixty years. And to get there, all we have to do is what we do best: experiment.

(This post now has a followup here.)

I think your key connection here, which I, a military historian, had not made until now, is that peer review came out of those heady days of the early Cold War when THE EXPERTS arrived at the Pentagon. The most famous of these was MacNamara. I leave the Vietnam analogy in your capable hands. From my perspective, this is the moment when scientists were being asked to think unthinkable things and question every set of assumptions until they had exhausted all cognitive powers, for the stakes were so very, very high. We may forgive the motivations and still see the shortcomings here.

I should also note that this all fits with Max Weber's theory that specialist classes make informational gatekeeping processes into safeguards for their own status. Terry Shinn wrote about it studying L'Ecole Polytechnique and I have encountered it in my own study of the French naval engineering school. If you want to add this to the social history of how entire professions can fail together, for decades, there is historiography.

I don't think it failed perhaps as much as it stopped working, especially as the number of scientists exploded. A good idea becomes a bureaucratic nightmare with scale.

Also the weak link point is excellent!