Photo cred: my dad.

(This is a followup to my recent post about grant funding. It generated a lot of discussion, so at the end of this post I respond to some of the critiques and questions.)

We apply for everything: scholarships, internships, jobs, promotions, apartments, loans, grants, clubs, conferences, prizes, and even dating apps. A kid today might apply for every school they ever attend, from preschool to graduate school. Even if they get in, they’ll find they’ve merely entered the lobby, and every room beyond requires another application. Want to join the student radio station, take a seminar, or work in a professor’s lab? You’ll have to apply. In undergrad, being unpaid tour guide required an application––and 50% of people were rejected!

Google ngrams suggests the application apocalypse is about a generation old:

All of this applying takes an incalculable toll. How much of our lives do we spend writing personal statements and cover letters, formatting resumes, taking standardized tests (and, if you have a few bucks and a clue, test prep), bugging people for recommendations, filling out forms, prepping for interviews, flying to interviews, crying after interviews, doing second-round interviews, crying after second-round interviews, waiting weeks to hear back, and getting rejected more often than not? To say nothing of the people on the other side of the process who have to sift through every application, conduct every interview, and turn down most people. That’s a bit like coming home with bag full of groceries, taking out the one frozen pizza you actually wanted, and throwing the rest away.

And then there’s the literal costs. Harvard, for example, charges a $75 application fee, and 57,786 people applied last year. Let’s assume that the average number of applicants used a fee waiver (44%), even though actual proportion is probably much lower. That means applicants pay Harvard at least $2.4 million every year, and the only thing 96% of them get in return is a rejection letter.

That’s not even the worst part. The worst part is the subtle, craven way applications irradiate us, mutating our relationships into connections, our passions into activities, and our lives into our track record. Instagram invites you to stand amidst beloved friends in a beautiful place and ask yourself, if we took a selfie right now would it get lots of likes? Applications do the same for your whole life: would this look good on my resume? If you reward people for lives that look good on paper, you’ll get lots of good-looking paper and lots of miserable lives.

The problem with picking people

Applications might be all right if we knew that they worked really well. But we don’t know that.

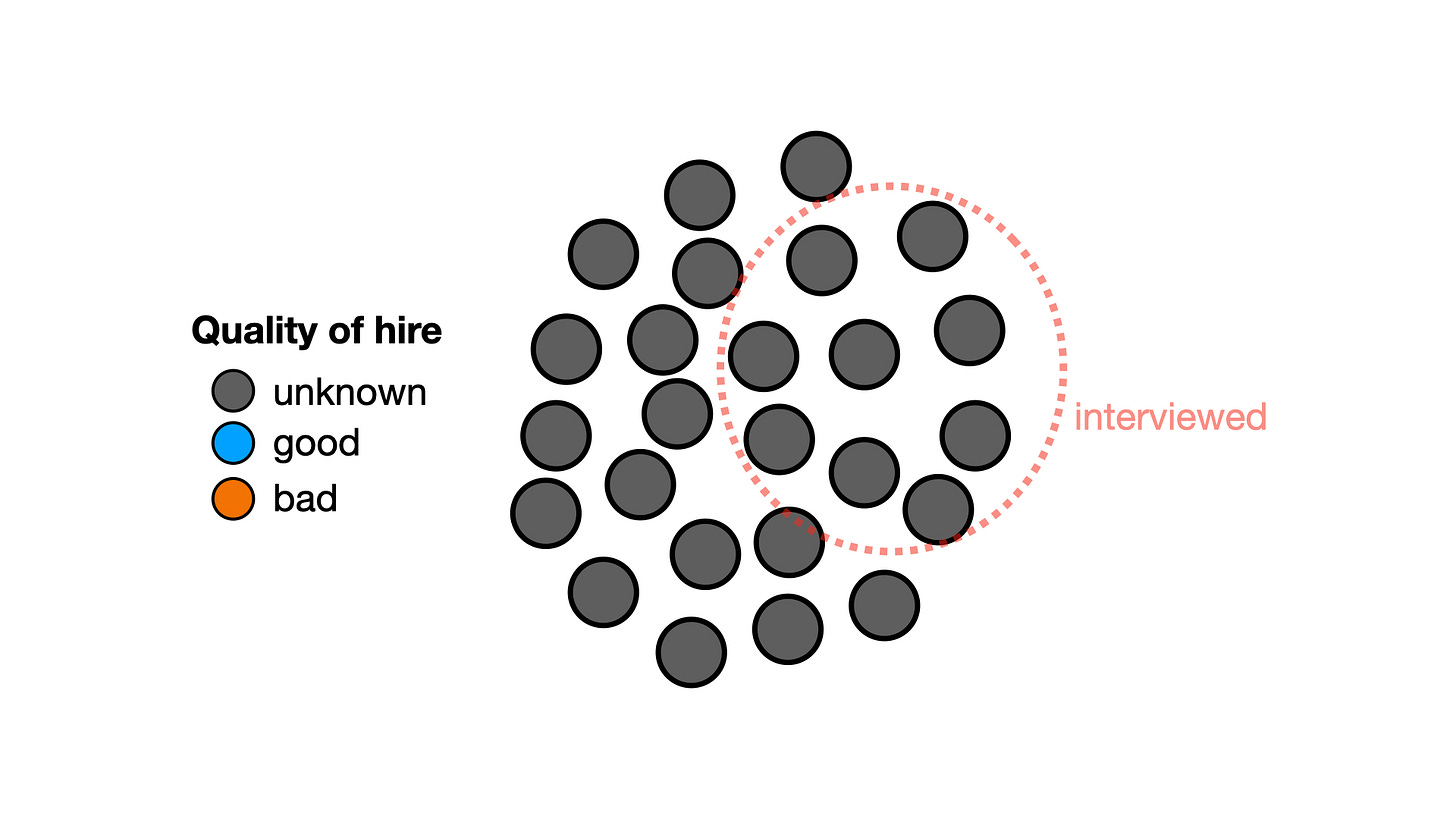

Say you’re a hiring manager at Big Corp and you post a job opening. You get a bunch of applications. Some of these people are probably good hires and some are bad hires, but you won't know who is who until you hire them.

You can’t hire them all, so you pick people based on their applications. Some people’s resumes and cover letters seem better than others, so you fly them out for an interview.

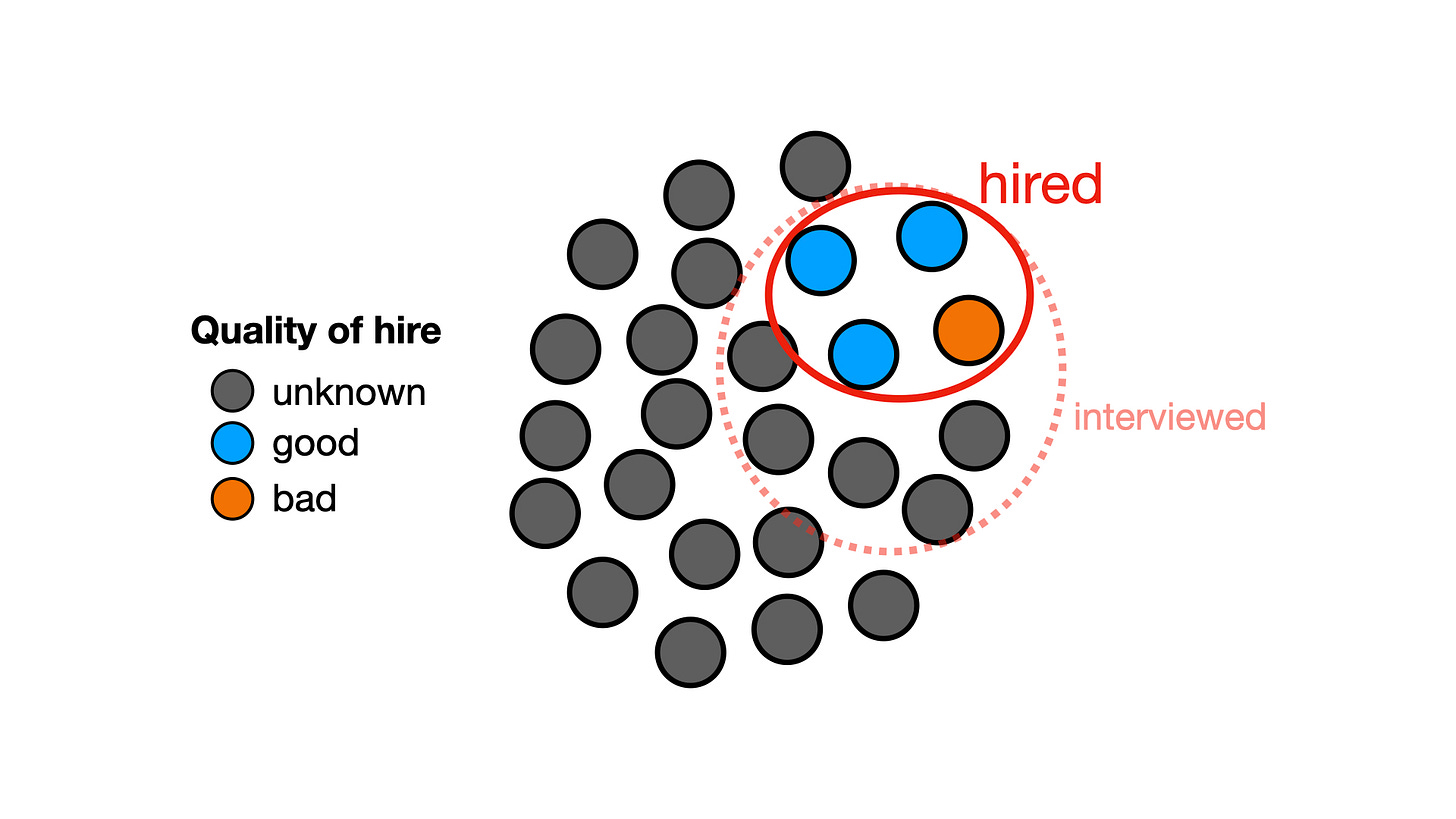

Then some people interview better than others, so you hire those people. As time goes by, you have a pretty good sense of who was a good hire and who was a bad hire. And you did pretty good: 75% good hires!

But if you had the God’s-eye view of all your applicants, you might find out that 75% of all of applicants were good hires!

You would have done just as well picking at random. All the time you spent reading applications and interviewing candidates was totally wasted.

You might think this wouldn’t happen, and maybe it wouldn’t. But right now you’re investing lots of time and money into hiring people, and you have no idea if you’re doing better than chance.

There is an easy way to figure this out. All you have to do is read the applications, do the interviews, decide who you would hire, and then hire people at random from the full pool of applicants. Of course, tell nobody that you’ve done this. Later, compare the people you would have hired to the people you would not have hired. If your potential hires were so much better that they would justify the costs of doing applications and interviews, congratulations! You’re good at hiring people.

Nobody’s going to do this because it sounds insane. You can’t hire at random; you might hire a psychopath!

And yet, you’re already hiring psychopaths. Everybody’s worked with someone terrible. Some terrible people are great at applications and interviews. Those are the scariest people of all, and your current system selects for them.

A tour of alternate worlds

If we were willing to experiment with applications, maybe we could figure out how to do them better. But maybe we need more than tweaks and patches on the current system. Maybe we need to imagine whole new worlds where people-picking happens very differently.

Here are six of them.

The United States of Drumline

In the classic Nick Cannon film Drumline, lower-ranked drummers may challenge higher-ranked drummers to a drum-off. If the lower-ranked drummer wins, they move up a rank.

In the United States of Drumline, all jobs work this way. Upstart lawyers challenge partners, office workers challenge their managers, undergrads challenge grad students who in turn challenge professors. Higher-ranked workers who lose a challenge don’t necessarily move down a rank; it depends on whether the organization can accommodate an additional employee at the higher level. The rules and format of the challenges are set by professional bodies that are, by law, comprised of people at all levels of the profession.

Education looks very different in the USD, since anything that doesn’t help you excel at your chosen profession is considered a luxury. No job requires a college degree or even a high school diploma, nor do companies consider prior experience or recommendations. All that matters is whether you can win a challenge.

To discourage excess challenges, initiating more than one challenge every six months is forbidden in the USD, though this law is currently being challenged.

Bellamyville

Bellamyville takes a page from Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel Looking Backward: the more people apply for a job, the less it pays.

The good people of Bellamyville believe that high rejection rates mean an opportunity is overvalued, so it needs to be made less attractive. Being a CEO, for example, is very prestigious and commands a lot of power, so there's no reason why it also should pay millions of dollars. They also believe that people only do crappy jobs out of desperation, which is unfair. It makes no sense that some of the least desirable activities, like cleaning toilets, also pay the least.

In Bellamyville, then, very fun jobs like musician and professional athlete pay subsistence wages. On the other hand, you can earn big bucks working at a call center or a rental car desk, so many people do it for a year or two to save up money.

Goodhartland

There is one law above all others in Goodhartland: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

As such, Goodhartlandians consider all applications ludicrous. Why would you want to get information about job candidates from the candidates themselves?

Thus, in Goodhartland, applying for a job simply means sending in your name. The company will then evaluate you without your knowledge. They’ll hunt down information about you online, send spies to your neighborhood, and interview your contacts without revealing their true purposes. It’s not uncommon for a company to subject candidates to secret tests, like placing someone with a broken-down car along the route you take to work and seeing whether you stop to help them.

This secret evaluation goes both ways. Companies who want to hire you will simply notify you that they are interested, and you take it from there. Maybe you’ll call them posing as a client, or strike up a conversation with an employee on the subway, or just show up to the office and snoop around until someone catches you.

Citizens of Goodhartland are always a little paranoid, but they are very well behaved.

Roulettistan

Roulettistan was founded by idealists who thought Goodhartland didn’t go far enough. They believe that every selection process will eventually be captured, even the clever ones used in Goodhartland. The only trustworthy selection process, they say, is one that is unknowable beforehand.

You could simply pick people at random, but some people truly are better at some jobs, and we want to find them. Thus, every company obsessively measures what makes their employees good at their jobs––conscientiousness, intelligence, friendliness, etc. Then, once someone applies, the company simply picks one of those traits at random and evaluates the applicant based on that trait alone. There are hundreds of possible traits, and each could be measured in dozens of ways, so it’s impossible to prepare for all of them.

Of course, this means randomness governs much of life in Roulettistan. But, as Roulettistani philosophers point out, randomness in fact governs all of life; other countries merely pretend otherwise.

Selectopia

Everybody in Selectopia knows that people send too many applications. Attracting a lot of applications doesn’t lead to better hires, it costs the company money, and it wastes applicants’ time.

Organizations in Selectopia thus try to minimize the number of people who apply for their positions. They don’t advertise much. They always evaluate applications on a rolling basis. And whenever possible, they try to skip applications entirely and reach out to candidates directly. Selectopians know that the best way to get opportunities is to post their work online, be active on social media, and make a good impression on the people they meet. “The best job application,” they like to say, “is being a good person."

Internesia

Why would you pick people by having them talk about a job instead of just having them do the job?

In Internesia, hiring works like this:

A company posts a job.

The first person who shows up and meets minimum qualifications becomes an intern for that job. (All interns are paid.)

If the company doesn’t like the intern or the intern doesn’t like the company, they part ways.

Internesians see doing lots of internships as an important part of developing as a person. How can you know what you like before you do a lot of things? And to them, sticking around a job you hate is a very bizarre form of self-sabotage.

Greetings from Applicatia

All of these worlds have their pros and cons, and I’m not saying any of them is obviously better than our own. But we don’t live in some default world that floats above this fray. We have, whether purposefully or not, made decisions about how people get opportunities.

We live in Applicatia, a world where people must spend their days improving their resumes in the hope of improving their lives. College debt, credentialism, application fees, biased interviews, fear of switching jobs––we’ve accepted these costs. And because we’re afraid to experiment, we can’t even be sure of the benefits. The only way to tell whether we prefer living in this world is to try visiting some others.

Trust Windfalls: the followup

One potential antidote to applications is Trust Windfalls, which I proposed in my last post. Basically, instead of doing grant funding via applications, you give money to a trusted Agent. The Agent picks people they trust to receive a big influx of cash, and then they nominate the next Agent, who does the same.

Half of people loved the idea and half of people hated it. When one person describes your idea as “game changing” and another says it’s doomed to fail, maybe it means you’re on to something.

Not surprisingly, Trust Windfalls turned out to be a Rorschach test for whether you trust people or not. I’m a guy on the internet going “hey give me a bunch of money and I’ll give it to my friends and it’ll be great!” If you trust me, that probably sounds fine. If you don’t know me but you’re optimistic about humanity, it may sound a little risky but still enticing. If you don’t know me and you’re a bit of a misanthrope, this sounds like the worst idea ever.

There’s really no way around that. And unless you have a couple million dollars to spare, it doesn’t matter anyway. But I encourage you to imagine yourself as an Agent responsible for distributing Windfalls. Do you think you would do a good job? Could you pick someone who would? If the answer is still no, no wonder you hate the idea! All I can tell you is I live in a very different corner of the world.

(I’m not saying that being skeptical of Trust Windfalls is a sign that you shouldn’t be trusted, but if you think the world is full of villains who want to screw you over and reward their evil friends…maybe you have insider knowledge?)

Here are some more specific answers to people’s questions and critiques.

Wouldn’t it be better to randomize grants? (Cody Kommers @ Against Habit & others)

Randomization is always the baseline to beat, so I appreciate Cody and others bringing it up.

My hesitation with awarding grants randomly is that you need to prevent people from trying to win your grant-lottery by stuffing the ballot box. If you limit applications to one per person, you incentivize everyone to get their friends and family to submit applications on their behalf. You could require applications to clear some quality control checks, but if your bar isn’t high enough, people will just put a little extra effort into their bad faith entries to get them in. If your bar is too high, you incentivize people to hack the application and you potentially slide back into rewarding success (can anybody apply for a Random Grant, or do you have to have, say, a college degree?).

Regardless: let’s run the study. Compare conventional grant funding to random allocation and to Trust Windfalls. At least we’re trying something!

To be clear, though, if randomizing grants turns out to be the best option, that’s pretty embarrassing. We really can’t find any signal in the noise?

Speaking of signal––

How would we measure whether this way of doing grants is better? (Rohit @ Strange Loop Canon)

This question would be easier to answer if we had any idea how well we’re doing with conventional grant funding right now, but unfortunately the metrics are terrible. Publications and citations are poor proxies for science quality. Outside of science, we’re pretty much lost.

My hope is that the difference between Trust Windfalls and anything else would be big enough to see the with the naked eye, however you want to measure it. And if we can’t tell the difference, we should favor Trust Windfalls because they have no application costs.

Don’t conventional grants already rely on trust, to negative effect? (Nickolaus Kriegeskorte and others)

When you trust someone, you don’t make them spend weeks applying and interviewing to get money from you, nor do you force them to use the money for one purpose only and sue them if they use it for anything else. Conventional grants do all that, so they don’t use trust in the way I’m talking about.

I think what people mean is something like this: you’re applying for a grant and you happen to have some connection to someone evaluating the applications. You went to grad school with them, or they know your spouse, or they do similar work. That maybe tips the scales a little bit in your favor.

You might think this is bad because it relies too much on trust; I think it’s bad because it doesn’t rely on trust enough. If you’re going to entrust someone with millions of dollars, you shouldn’t just be acquainted with them; you should know them inside and out. In conventional grants, a dash of trust might be worse than none at all, but an abundance of trust beats both.

Plus, it’s wrong to act as if an application process is fair to all when in fact some people get preferential treatment. Trust Windfalls dispense with that pretense. And conventional grants give a lot of power to a few people’s prejudices, whereas Trust Windfalls are subject to many people’s prejudices, which are more likely to cancel each other out.

Wouldn’t Trust Windfalls be full of bias, recreating the old boy’s club? (Shai Davidai and various folks on Twitter)

The only way to award grants with zero bias is to give them out randomly with every person on Earth having an equal shot. If we want any amount of selectivity, we’re going to risk bias. I think Trust Windfalls would have less bias than conventional grants, for a few reasons.

First, there’s bias at every stage of the prestige pipeline––college admissions, graduate school admissions, fellowships, hiring, promotion, etc.––and conventional grants only reward people who make it through them all. So even if you stamp out every bit of bias from grant funding, you’d still be rewarding a very biased sample of people. Trust Windfalls at least have the possibility of going to people who left the pipeline at some point; conventional grants do not.

(I think some people assumed that I was saying we should do science funding via Trust Windfalls for professors only. To be clear: I think Trust Windfalls should be open to everybody and being a professor, or anybody else, shouldn’t count for jack.)

Second, we have a very long and poor track record of removing bias from established systems. I believe structural racism is part of the reason why Black and Hispanic Americans are underrepresented among STEM PhDs, for example, and progress has been painfully slow:

There are people trying to improve this. The NIH is trying. People in the Harvard psychology department are trying––including me; I mentor students in this program. I’m sure there’s lots of stuff like this out there. I think these efforts are good and I hope they continue.

But sticking to the status quo means accepting this rate of change, and I don’t accept it. I think we can do better, and it will require radical experimentation. I think Trust Windfalls are a worthy experiment. If you disagree, let’s see who’s right!

I am in the process of giving my assets to education and I think your Trust Agent method is beautiful for many reasons. I am a retired Professor of Theoretical Chemistry and am funding projects at 5 major universities. I will soon have 3 Agents. If you have ever participated in the sheer lunacy of applying for a research grant, your method is most appealing. Thanks,

RNK

Interesting notions, if also as illustrations of how chesterton's fence came to be so.

One note on the increasing fervour with applications is that this often coincides with these fields becoming overall much larger. The circle being: larger candidate needs = requires rigorous standards = need for gatekeeping + credentialism = legible application processes = larger candidate pools (I looked at this in terms of wage effects and found HR becoming more important since there were more applicants - https://www.strangeloopcanon.com/p/understanding-wage-stagnation).