Can you kill God with laser beams and atom bombs?

Testing a very old hypothesis

Photo cred: my dad.

I was an atheist for a while when I was 12. I got sucked into an online message board dedicated to the Japanese anime Yu-Gi-Oh! (long story) and got caught up in the casual godlessness that flourished there. This was unfortunate for me, because I was going to a Catholic school at the time and every single person I knew was a believer.

I got pretty resentful about living an atheist double life, and I developed a sort of spiteful, pre-teen psychology of divine belief, which went something like this:

It was easy to believe in God when we couldn’t explain why a big fireball streaks across the sky every day, or why people get sick, or why the earth sometimes shakes. Ours was a God of the Gaps, a deity who explained all the stuff we didn’t know. But as we learn more about the world, the gaps close and God gets squeezed out. The inevitable progress of science means that people will eventually stop believing in a celestial grandpa who dispenses miracles. In fact, many have already.

My faith was born again in high school as hipster Christian spirituality and then faded into benign I-dunno-what-I-am-ism, but I always held onto this idea that belief thrives in ignorance, and that the light of knowledge will one day banish it. And I’m not alone: historians, sociologists, and intellectuals of all sorts have said similar things, including such heavy hitters as Hume and Freud.

I decided to put this hypothesis to the test, and I’m here to report: it failed.

Before we get started, let’s get two things clear. First, I’m only interested in people’s belief in some supernatural God-like thing––let’s call that divine belief––and whether it recedes as science advances. Divine belief is separate from all kinds of religious beliefs, like whether we should worship saints, whether Lutheranism is right, or whether God wants you to wear a hat or not. Church attendance and religious identification, for example, might go up and down for lots of reasons independent of divine belief, like inquisitions or identity politics. I’m concerned with God in hearts, not butts in pews.

Second, I think it is totally fine to believe in God or not. Whether science saps divine belief is an empirical question, and I don’t recommend staking your own divine beliefs on the outcome. I think there’s a Big Something out there, but that’s just me.

With that out of the way, let’s go back in time.

I. Ancient atheists

If we believe in God because we need a magic guy in the sky to explain all the mysteries of the world, it should have been hard to deny that guy before we started solving those mysteries. Some historians really believe this, from Lucien Febvre a generation ago to Peter Watson today, who wrote that the Enlightenment thinker Montaigne "never really doubted that there was a God because to do so in his lifetime was next to impossible."

And yet unbelievers existed long before the invention of modern science, just as believers continue to exist long after. As early as 600 BC (and probably much earlier), the Cārvāka in India were claiming that there is nothing beyond what the senses can perceive. Strands of ancient Chinese philosophy had no need for gods. In the West, we can hear the voice of an ancient atheist in Euripedes' play Bellerophon (c. 400 BC):

Is there anyone who thinks there are gods in heaven?

There are not. There are not, for any man who wishes

Not to be a fool and trust some ancient story.

Medieval church records are stuffed with accounts of people hauled in for all sorts of proto-atheism: there is no soul, Jesus was a fake, heaven and hell don’t exist. Some of these are no doubt trumped-up charges––accusing your neighbor of atheism is a great way to get him hauled off so you can steal his goats––but some of these are real people who felt this whole God thing just didn’t add up.

These ancient unfaithful prove that people were capable of divine unbelief long before we invented Erlenmeyer flasks and randomized controlled trials. They asked: if people have souls, how come nobody has ever seen one? If there’s life after death, why hasn’t anyone returned? If God loves us so much, why does he allow evil to exist? Some people were satisfied with the answers their holy men had for them, and some weren’t.

So, people can reject the supernatural even if they don’t know where rain comes from or what the spleen does. That’s strike one against the God of the Gaps hypothesis.

II. (Don’t) mind the gaps

Still, isn’t it easier to be an unbeliever today? Ancient atheists didn’t have physics and biology to lean on when challenged by believers: “If God doesn’t exist, where did the Earth come from? Who put all the people here?” Modern atheists can smugly respond “the Big Bang and evolution, respectively.” Having an intellectual off-ramp ought to make it easier to exit the faith, and the wider the ramp, the more people should exit.

If that’s true, even if there were already some faithless folks in the past, we should see their numbers tick up and up over time. Maybe not all at once, maybe not quickly, and maybe not linearly, but inevitably and noticeably.

Has that happened? Unfortunately, for most of history, it was hard to get a precise headcount of the godless (though this was fortunate for the godless themselves, since their heads tended to get removed whenever counted). Avowed atheists certainly got louder during the Enlightenment, but it may have been the rules of discourse that changed, rather than the prevalence of unbelief. The United States had several Great Awakenings where people got all excited about God, which implies several Great Slumberings where divine belief might have ebbed, but people can believe in the divine perfectly well without getting together in a field and shouting about it. No historical event or philosophical treatise can give us an accurate estimate of unbelievers or tell us whether their numbers were creeping upward.

That all changed in 1944, the first year the Gallup Organization simply asked Americans, “Do you believe in God?” and 96% said yes. (Only 1% gave a straight no; the rest didn’t give an opinion, didn’t know, or refused to answer.) If there was a rise in atheism over the past few hundred years, then it was a very, very slow one, so slow that it could easily be mistaken for no rise at all.

Indeed, belief in God stayed at essentially 100% in the US for the next 20 years. Humans split the atom, discovered DNA, and sent a satellite into space––none of it made a dent. When Gallup asked again in 2011, still 92% were God-fearing. The most recent number was 87% in 2017.

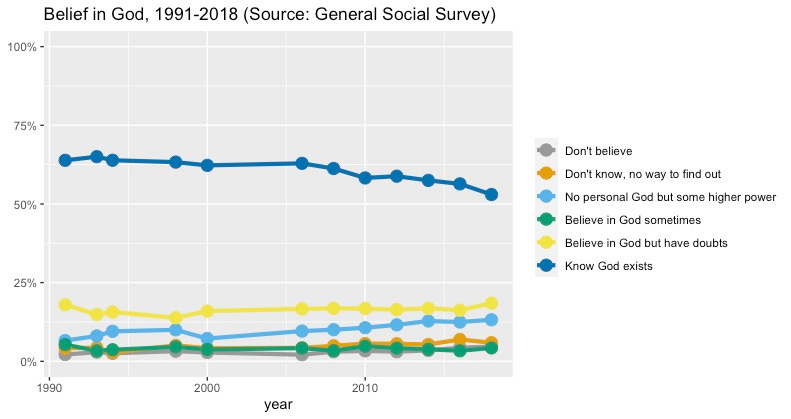

The General Social Survey––the preeminent inventory of American attitudes––tells a similar story. Belief holds steady, then dips in 2008 and again in 2018.

That's a decline, but an awfully small one, and there are two reasons to be skeptical that science is the culprit. First, why does belief stay stable for decades and only start inching downward about 15 years ago? What recent scientific insight closed the last gap for God to hide in? Second, notice the “don’t believe” (gray) and “no way to find out” (orange) contingents stuck at 1990 levels while the “some higher power” (teal) contingent inches upward––it seems like God-fearers are softening their stance rather than rejecting God outright.

Could people be lying, covering up a more dramatic decline? More people deny God when you ask them in sneaky ways that preserve their anonymity, so maybe people really are giving up their faith but not telling pollsters. But it’s equally possible that any declines in belief that do show up are simply the result of people becoming comfortable claiming the unbelief they always had. No longitudinal studies use the sneaky questions, so we don’t know how much latent atheism we could have detected in the past.

I’m skeptical that there’s a huge upswing in unbelief that we just aren’t capturing. It’s more socially acceptable to admit your atheism than it was a decade ago, thanks in large part to New Atheists like Richard Dawkins, who made a such a big stink about religion in the 2000s that he sold millions of books and earned the greatest recognition of all: ichthyologists named a genus of cyprinid fish after him. Americans also like atheists more than they used to. Yet despite an increasingly favorable climate, today only 4% of Americans call themselves atheists, and only 5% call themselves agnostics; that’s virtually unchanged since 2009.

Overall, then, there’s little evidence that centuries of science have chased the faith out of people’s hearts. Strike two against the God of the Gaps.

III. There’s a gap for that

Maybe belief in the divine persists because there are lots of gaps left. Sure, we’ve got rocket ships and laser beams and nanotubes, but we still don’t really know why people get headaches, or what consciousness is, or why there’s something rather than nothing. These gaps seem plenty big to fit some God inside.

There’s pretty good evidence, however, that shrinking the gaps doesn’t shrink people’s faith very much. We have a patented gap-shrinking process called college, where people spend years just learning stuff. If people turn to the divine because they can’t explain the world around them, college ought to turn them away.

But it doesn’t, really. College graduates adhere to religion less, but the difference is much smaller than you might expect:

Education doesn’t seem to affect Christians at all:

In fact, college might not do anything to divine belief. Unbelievers may be more likely to go to college in the first place, so what looks like an education effect might just be a selection effect. Indeed, college students are already less faithful than the rest of the country when they show up at their freshmen dorms. Anybody who is an atheist after graduation was probably an atheist before matriculation.

If four years of additional knowledge doesn’t shake people’s belief in the divine, it suggests their faith wasn’t based in ignorance in the first place. That’s strike three against the God of the Gaps, he’s outta here.

IV. Extra innings

You’re supposed to stop at three strikes, but lots of people have believed this hypothesis for hundreds of years, so I think it deserves a fourth.

I presented data from the last half-century as if we’re all living in the age where science really got going, but that’s just chronological hubris. If science was going to eradicate faith, why didn’t it happen when Copernicus displaced the Earth as the center of the universe, or when Darwin discovered natural selection, or when Salk defeated polio? These breakthroughs upended humans’ understanding of their worlds and made many people very upset or, in the case of the polio vaccine, euphoric:

People observed moments of silence, rang bells, honked horns, blew factory whistles, fired salutes, kept their red lights red in brief periods of tribute, took the rest of the day off, closed their schools or convoked fervid assemblies therein, drank toasts, hugged children, attended church, smiled at strangers, and forgave enemies.

You might have thought that while science was killing one invisible enemy, it might have killed God too. But it didn’t.

So why should we expect any subsequent discoveries to do the deed when they’re way less exciting than that? The timeline of science gets awfully boring when you hit the year 2000. Apparently capturing the God particle did not inspire anyone to blow factory whistles or convoke fervid assemblies, and it did not do much to our belief in God either.

V. Goodbye God of the Gaps

The God of the Gaps hypothesis is, at its core, a cynical theory about other people’s beliefs: some people need a divine security blanket to comfort them in a dark, mysterious universe, but I, of course, do not.

Accordingly, while many say that science conflicts with religion, few say it conflicts with their religion. No faithful person claims they’ll stop believing in God if someone can prove that, say, for any simple gauge group G, a non-trivial quantum Yang–Mills theory exists and has a mass gap Δ > 0. Nor does any atheist claim they’ll start believing in God if On the Origin of Species gets retracted.

So why has everyone from David Hume to 12-year-old me foretold a godless future? I think we’ve all had a bad faith theory of bad faith. We did what everybody does when we disagree with someone: call them stupid and prophesy their extinction.

I can’t speak for Hume, but I should have known better. When I lost my faith for a while in the early 2000s, it wasn’t because I read a science textbook; it was because I started hanging out on a message board with a bunch of cool atheists. And when I got it back, it wasn’t because the world was suddenly full of mysteries that needed divine explanation; it was because I started hanging out with a bunch of cool Christians. I didn’t care about gaps or lack of them. I just wanted to be cool.

Even today, after taking a solemn vow of science, my own belief in the Big Something comes down to…a feeling. I didn’t logic myself into it, run a study, or fit a regression model. It’s just that when I ask myself “is there a Something out there" my gut says “yes” and when I ask “what is it like” my gut says “Big.” Asking much more about it is both useless and nonsensical, like wondering whether the tortellini I’m making for lunch are Marxists.

I think that’s how most people’s divine beliefs work. There may be a thick outer crust of reasons, but a core of molten feeling lies below. Whatever puts the feeling there, it’s not in this month’s issue of Scientific American.

If I had a time machine, after killing Hitler in 1889 and buying a thousand Bitcoin in 2009, I would visit my angry, atheist, 12-year-old self. I would tell him that I know how easy it is to get carried away on self-righteous resentments, but every moment spent feeling spite is a moment wasted, and you have a limited amount of moments. I would tell him that his little God of the Gaps theory belongs not in academic journals, but in the pantheon of uncharitable self-other asymmetries. And I would tell him that everything is okay, that he is a cool young man, and that one day he’ll be so cool, in fact, that literally dozens of people will read his blog.

People seem to believe what their parents believe. Sometimes cool friends, when you are 12, or college buddies, when you are 20, can draw people in other directions, but the influence of one's group seems to be a major determinant. How many believers, yourself excepted, have thought for themselves in this matter?

I think there are good reasons why this is so: A human baby doesn't know whether it is born in a cave 50,000 years B.C., or in a mud hut, or a castle, or in the land of internet gadgetry, or in a 31st-century pod orbiting Alpha Centauri. So natural selection has built them to learn from their environment and learn quickly. The fastest way for babies to figure out how its world works is to do what the people around them do. It is so adaptive a rule that it becomes our default. It might even explain how religions got started,: When posed with a mystery, we turn to our parents, then to wizened elders, and then to the great father in the sky. So I think we can ultimately lay the blame, or credit, on the principle of reinforcement and its associated process of generalization.

> That's a decline, but an awfully small one

going from 96% to 92% to 87% is a pretty big decline!

Framing it as "the number of athiests doubled from 1944 to 1990, then doubled again from 1990 to 2011, then doubled again from 2011 to 2018" makes it seem like atheism is trending up from a very low baseline.

I don't know if it vindicates the God of the Gaps, but I don't agree that athiesm is flat either. Preference falsification could also be hiding a lot of athiesm, like the Gervais and Najle article found, so it could be the curve is even steeper upwards!