Disclaimer: I’m not the kind of psychologist who treats people. These are just things that happened to me.

In October 2020, I began to feel very, very bad.

It was a mental bad, a bad in my head. I don’t know how to explain what I felt other than this: in the book Dune, there’s a scene where a nun comes to test the protagonist, a kid named Paul. She shows him a box and tells him to put his hand inside it. “What’s in the box?” he asks. “Pain,” she says. She cranks up the pain-box and it’s Paul’s job not to take his hand out, or the nun will kill him.

(I went to Catholic school, so I can confirm this is standard practice.)

Anyway, it felt like I was sticking my whole head inside a pain-box. It didn’t feel like sadness, exactly. It didn’t feel like anger or loneliness or regret or any other negative emotion I knew. It felt like pure, undifferentiated bad. On the worst days, I would wake up and experience a half-second of peace and then the badness would come flooding in, like someone had taken a pickaxe to a big pipe inside my head marked “MISERY.”

I don’t know exactly what to call the thing I felt. “Mental health” and “mental illness" feel corporate and euphemistic, the kind of phrases you use when you’re trying to sell a meditation app, or when you’re explaining to your boss why you didn’t finish the PowerPoint on time. I prefer to think of my experience as having a skull full of poison.

I thought I was pretty in-the-know about this whole skull-poison thing. I had been a resident advisor for most of my twenties, so I had been through every mental health awareness training ever devised. I had sat with friends through panic attacks and depressive episodes. My sister has a PhD in counseling psychology; I got my own PhD alongside clinical psychologists. I had all the Right Beliefs: depression isn’t just big sadness, there’s no shame in seeking help, etc.

And yet, having a skull full of poison was nothing like I expected. Not even close. People told me it would be bad, and it was. But no one told me it would be weird, so I’d like to tell you, in case you should ever meet this bizarre menagerie of mental experiences.

#1: THE ALCHEMY OF POISON

First: I assumed that bad feelings in your head come from somewhere. A breakup, a death, a job where people yell at you. But my bad feelings seemingly came from nowhere.

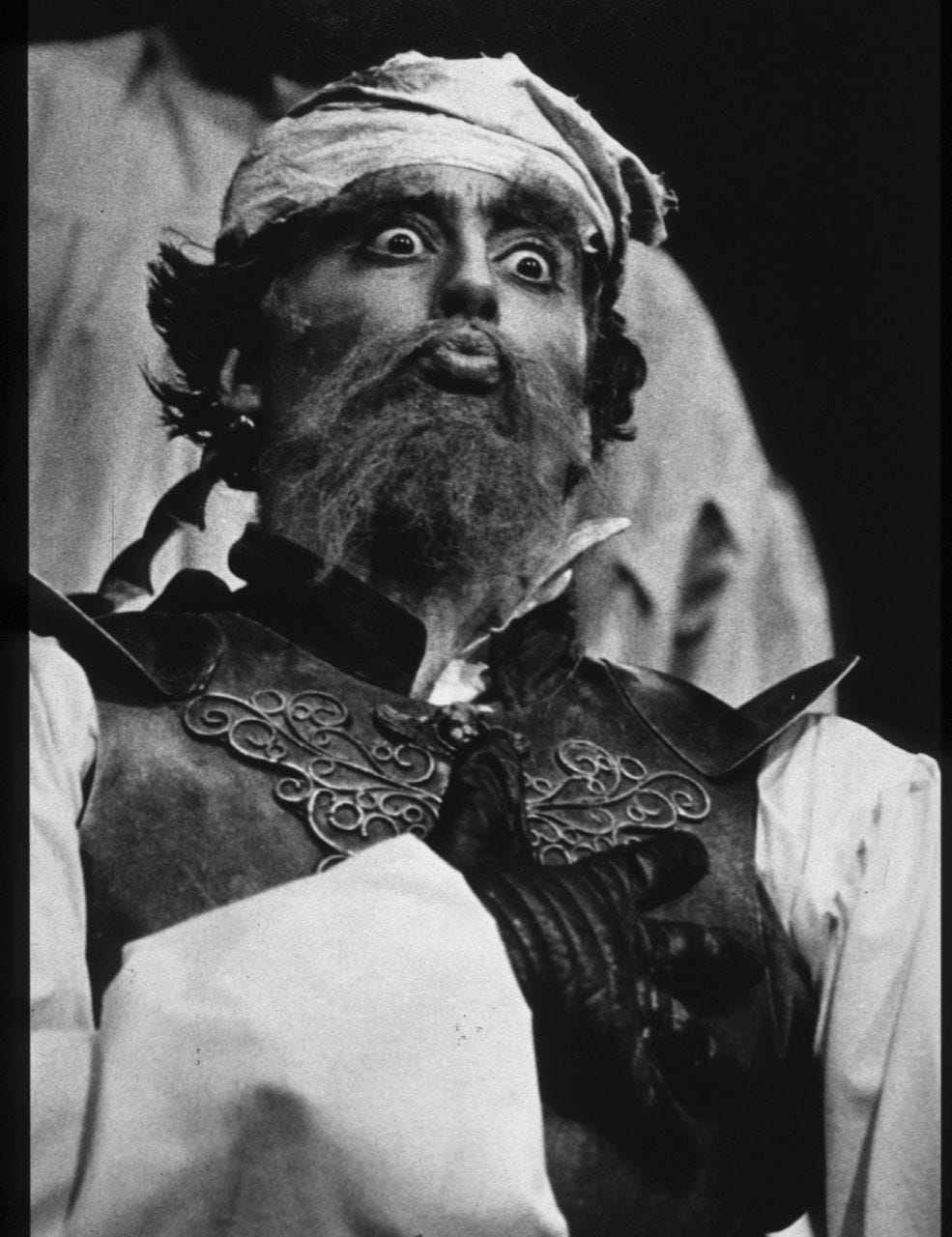

Yes, it was a global pandemic and millions of people were dying, but I, like every good American, had gotten used to that. I was in a pandemic groove, writing my papers in solitude during the day like a monk (and growing the scraggly facial hair to match), going for long walks in the afternoon, playing Call of Duty at night, and seeing my pandemic podmates on the weekend. I lived in a dorm, so every meal was provided for me in a nice little takeout box. Most days, the only words I would speak to another human in person were, “I’ll have the mac and cheese, please.” It wasn’t a terrific existence, but as far as global pandemics went, mine seemed all right.

So when I started to notice the poison in my head, I had no idea why it was happening, and because of that I had no idea what was happening. “Maybe I’m stressed, or I’m not having enough fun,” I thought, but I felt just as bad after spending a day vegging out or hanging out. “I must be tired,” I thought, but no amount of sleep or caffeine helped. In fact, caffeine suddenly became poison itself. My afternoon cup of tea, rather than making me feel perky and pleasant like it normally did, would instead turn the misery-spigot on full blast.

Where was the poison coming from, and how could I stop it? That was the second weird thing: trying to answer those two very reasonable questions was exactly the wrong move, like diving into a whole lake of poison.

#2: LOOKING INTO THE LION’S MOUTH

You know how, when you get a text, your brain goes “LOOK AT PHONE RIGHT NOW”? And how, if you don’t look at it right away, you brain gets louder and louder, like “UM HELLO?? PHONE!!”? And if someone locked your phone in a box and you heard a bunch of notifications come in you’d get really antsy and be like “hey dude I really gotta get into that box right now!!”?

Okay, now imagine that same feeling but for thoughts. Like a thought pops up, and your brain goes “THINK ABOUT THAT THOUGHT RIGHT NOW.” And you know you shouldn’t think about that thought, because you’ve thought about it for hours today already, and you didn’t get anywhere, and it only made you sad. But your brain goes “UM HELLO?? THOUGHT!!”

There were two thoughts that would pop up in my head over and over. One was “I feel really sad right now,” and my brain would go “WE HAVE TO GET TO THE BOTTOM OF WHY WE FEEL SO SAD.” And I would say, please brain, we tried that earlier, And my brain would go “OK BUT WHAT IF THIS IS THE TIME WE FIGURE IT OUT?? COULDN’T HURT”.

The second thought was usually an answer to the first: “What if my very good romantic relationship is, secretly, very bad?"

Pretty much everything had been stable since the beginning of the pandemic, except for one thing: I had started dating someone. She was smart and cute and wonderful. After our first date in September, I went home thinking, “It can happen for me too! I can really fall in love with someone!” I hadn’t even seen the bottom half of her face yet—we were masked the whole time—and yet I already had a suspicion that she could be the one.

So when I was doing detective work on my bad feelings, this new relationship naturally came up as a prime suspect. “MAYBE BEING WITH THIS VERY GOOD PERSON IS ACTUALLY, SOMEHOW, BAD” my brain would say. “But everything’s so good!” I’d reply. “OK, BUT IF EVERYTHING IS GOOD, THEN WHY DO YOU FEEL BAD?” And so on. And on, and on. Sometimes for hours.

It’s difficult for me to explain just how crazy it felt to not think these thoughts. I felt like I was staring directly into a lion’s mouth, like I was on a plane and the pilot had just said “brace for impact,” like I had looked up and saw a meteor heading straight for Earth—how could I possibly think about anything else? It’s stupid, I know! But that’s how it felt. Like I said: weird.

#3: THE SEARCH FOR THE SECRET LEVER

The next weird thing was the get-better-quick schemes.

Part of the reason I kept thinking the same thoughts over and over was that I was pretty sure I just needed to think the right thought, and then all the poison would drain out and I’d feel better again. Here were some of my supposed breakthroughs:

"I just need to relax"

"It’s a pandemic, of course I feel bad!"

"Let yourself feel your emotions and then they’ll pass"

"Just stop thinking!"

"It’s okay to feel sad"

Each of these would provide somewhere between a few minutes and a few hours of relief: aha, I finally figured out! Happy times are here again! And then each of these thoughts would go careening out of my head, like how a cooped-up dog bolts for freedom when you open the front door. I would be left feeling terrible again, searching once more for the eject button that would launch me out of my sadness.

My friend Clayton, who wrote a one-man show about depression, even warned me explicitly that looking for a secret lever was futile. “I thought the exact same thing, and I was wrong,” he said.

Sounds like a guy who failed to find his secret lever! I thought, smugly. Too bad for him.

#4: IN THE MATRIX, YOUR MOM IS SCARY

Even weirder: nobody told me that, when you feel really bad, sometimes you can experience a whole grab-bag of inexplicable bad things.

For instance, sometimes things felt a little less real. I would feel like I was in a pop-up book, or the Matrix, or a pop-up book about the Matrix. Or like I was in a movie about my life, but I wasn’t playing me; I was just watching. Hard to explain, but it didn’t feel very good.

At one point, in December, I had a headache that lasted for six days.

Another day, when I was home, I woke up feeling afraid to go downstairs and talk to my mom. And my mom rules. There’s no reason to be afraid to talk to her. But there I was, lying in bed, worrying about what would happen when I went into the kitchen.

“I should probably go to therapy,” I thought.

#5: PLEASE HELP ME FIND A TACO

I’ve had “the talk” with plenty of distressed friends (“Have you thought about seeing someone?”). So I figured that the hardest part of getting a therapist is deciding that you want to see one.

Wrong. The hardest part of getting a therapist is finding one. They say they’re accepting new patients; they aren’t. They say they take your insurance; they don’t. You call them; they don’t call back.

When you want to, say, buy a taco, the full chorus of the internet swoops in to help you. Billions of people who have eaten trillions of tacos, and all they want to do is tell you which ones are good and which ones are bad. It’s great.

When you want to find someone who may, one day, prevent you from taking your own life, you’re on your own. Sometimes there’s a little blurb: “I am a mental health professional who likes to professionally help people with their mental health.” Sometimes there are five stars floating next to your potential therapist’s name—where do those stars come from? What do they mean? Not once could I find a review, someone saying “I was super sad and now I’m not, thanks doc!” I was making judgment calls like, “Do I want to reveal my most intimate secrets to a guy with a goatee?"

If you keep calling therapists, you might eventually get an appointment. But they can’t see you until three weeks from now, and when you get there you realize it’s not even an appointment where they help you, it’s just an appointment where you explain all the ways you feel bad and then they tell you if they can help you. The actual helping part will only come later, in the next appointment, which will be two weeks from now. I went to four appointments before my therapist said, “Okay, we're ready to start our treatment plan,” and I was like "wait what have you been doing for the past four weeks? Not treating me?"

(My therapist, Dr. E, was actually terrific and I was very lucky to find her.)

It’s amazing that anybody suffering from a serious mental illness ever finds help on their own. Navigating a senselessly confusing system with little hope of success is the last thing you want to do when you feel very bad, because everything feels like a senselessly confusing system with little hope of success.

#6: DEMONS ARE REAL

I got to therapy with all the puffed-up confidence of a guy who had taken a single clinical psychology class in college. I wanted evidence-based treatment. I wanted CBT. Correct my counterproductive thoughts! Flog my brain into shape! I knew that lots of therapists still use neo-Freudian nonsense; I wanted none of that. Only the good therapy for me, please!

Dr. E listened with the same kind of benevolent patience that I imagine Janet Yellen uses when she fields questions from senators who have had one semester of macroeconomics. “I’ll keep that in mind,” she said kindly.

She probably already knew what I would only realize later: I wanted to solve my bad feelings the way I had learned to solve everything in life, which is by being a diligent student and a good boy. But you can’t ace feeling good like it’s a math test, and trying only makes you feel worse. My recovery was going to be far more mysterious than I could possibly appreciate.

It’s a very weird experience to gain an advanced education in psychology, often feeling grateful that we don’t think of mental disorders as demonic possessions anymore, and then you go to therapy and your therapist says, “Imagine your bad thoughts are a demon, and whenever they appear, you slice them with a sword.” It’s even weirder to find this works.

#7: THE LSAT, BUT FOR YOUR OWN MISERY

After a few sessions, my therapist said something surprising: “What you’re describing sounds like anxiety.”

I immediately thought I had gotten a dud therapist. I didn’t have anxiety. Worrying that everyone at work thinks you’re a fraud, or that your eyes are too close together, or that somebody’s gonna kidnap your kids on the way to school—that’s anxiety. I was simply getting to the bottom of my most important problems by thinking about them a lot.

“Uh huh,” said Dr. E. “And how’s that going for you?”

“Honestly, not great,” I said.

She was right. I was doing the same thing as the guy who was worried that his eyes are too close together, but I was pretending that my worrying was a respectable intellectual exercise. I had dressed up my worries as LSAT problems and my anxiety as studiousness.

I wonder if this is the secret behind a lot of skull-poisons: you secretly think you’re not sick at all, and you believe that what you’re thinking about is actually extremely important. Yes, when other people think “I’m worthless” over and over, they have depression, but when I do it, I’m just contemplating reality, and what could be more important than that?

(Pop quiz: did I really “have” anxiety? Wrong question: anxiety doesn’t exist. It’s just a useful way of talking about a bundle of symptoms, like every other diagnosis in the DSM-5. Mental experience becomes real when you experience it, not when you figure out how to bill it to your insurance. In fact, my therapist probably didn’t diagnose me with anxiety at all, because I hadn’t met the six-month threshold for generalized anxiety disorder. She most likely told my insurance that I have adjustment disorder, which is a bureaucratically convenient way of saying “this dude’s having a tough time.”)

#8: PILLS PILLS PILLS

Here’s another weird thing: I thought that people would tell me whether I should take mind-altering drugs or not, but nobody did. I talked to a general practitioner who was like, “Hey bud, how about some happy pills? I got some right here.” I talked to a psychiatrist was like, “Up to you!” My therapist was like, “What do you think?”

I’m sure if you’re in a really bad place, all of these people start suggesting that you take the pills. But if you’re just in a kind of bad place, you might be on your own, stuck thinking things like “How sad am I? Am I really sad? Like, alter-my-brain-chemistry levels of sad? Also didn’t we figure out that depression isn’t just a lack of serotonin? Oh no, did I destroy the placebo effect for myself by reading that??”

It felt like making an informed decision about antidepressants required roughly one PhD worth of knowledge, and it was hard to acquire it since I was too busy watching clips of “Penn and Teller: Fool Us” on YouTube and crying for no reason.

In the end, I didn’t take the pills for four reasons:

I could still handle all of my responsibilities; I wasn’t in full-on crisis.

Other stuff seemed to be helping.

I was afraid.

I kind of forgot.

#9: ZOMBIE MODE

An uncomfortable truth: when you feel really bad, it’s easy to become boring and selfish. You get so obsessed with the tempest inside your head that you can’t focus on anything outside of it. You start seeing a therapist, then you start treating all of your conversations like therapy. Your bad feelings become a handy excuse for being a bad friend.

I’m saying “you”; I mean “me”. When I felt very bad, all I could think about was my own suffering. One of my best friends was struggling through a bad relationship at the time, and focusing on his problems for more than a few moments felt like trying to memorize a 100-digit number. I’d call friends, unload on them, and say, basically, “Enough of me talking about my anxieties. Now you talk about my anxieties."

At my lowest points, I’d go full zombie mode. I’d become nearly catatonic, speaking only to say “I’m fine” or some other placebo phrase designed to end any inquires into my internal state. Sometimes I’d cry. My girlfriend got the worst of this; I was too embarrassed to go full zombie in front of other people. One day, my zombification culminated in us going to see Fast and Furious 9 in theaters, because all I could do was sit still and take in stimuli. When you’re so sad that all you can do is watch Ludacris drive a car into space, you got a problem.

When I described zombie mode to my therapist, she said “Stop doing that.” I was stunned—aren’t therapists supposed to be, like, kind and empathetic and stuff? “The way you’re acting isn’t fair to your girlfriend,” she continued. “The next time you feel that way, go for a walk and straighten yourself out.”

She was right. (Like I said, great therapist.) I entered zombie mode only when I stopped trying to bale the misery-juice out of my skull and instead let myself stew in it.

This was not what I expected. I thought I needed to “work on myself” and “do some self-care." I thought I needed compassion and coddling. I didn’t: I needed a kick. The more I thought about other people, the less I thought about my own sadness, and the better I felt.

#10: BUCATINI

The last weirdness is the lasting weirdness.

I thought I’d recover from my skull-poisoning and everything would go back to normal, shipshape, better than ever, really! Redemption would have straightened out all the strangeness, like “ah yes, I get it now, this was all for something.” I mean, if there’s no arc, what’s the point? You just felt bad and then you felt less bad? That’s it?

For me, yes: that’s it. I do not feel better than ever, nor do I feel worse. I feel more capable, but also more fragile. I feel less certain of everything, even the most certain things. There’s no moral here, really, no great triumph, no party to celebrate draining the last ounce of poison out of my skull. (Does anyone ever get it all?) It’s just a list of weird things.

But after stumbling through ten strangenesses, maybe I’ve finally figured out the mistake I keep making: I expect my life to follow the rules of good narrative. Effects are supposed to have causes. The laws of the universe are supposed to be knowable and consistent. If something keeps coming up, it should be important.

Well, it ain’t like that. So I’m going to break the last rule of narrative, which is that it should all amount to something. You should tie it all together, leave each character permanently changed, give the audience a tune to whistle on the way out.

Instead, I’m going to make dinner with my fiancé. My girlfriend, the one my brain tried to blame for my sadness, stayed with me, we fell in love, and right now she's waiting for me to boil some bucatini. Life is weird, and that’s all right.

Yet another "damn, that was the best essay..." experience. Thanks, and keep typing.

I am a psychotherapist and a former pt gave me an image of EXPECTATIONS AND REALITY when it comes to treatment. The expectations is a smooth, continually upward moving line where the reality representation is of a line going all over the place, looping back on itself, getting tangled though coming out on the other end all the same. Also, one of my favorite quotes from Doctor Who about linear narratives: “People assume that time is a strict progression from cause to effect, but actually from a non-linear, non-subjective viewpoint, it's more like a big ball of wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff.”