Psychology might be a big stinkin’ load of hogwash and that’s just fine

Hello I would like to reach into your head and tear out the myths that you believe about my beloved field

About 10 years ago, a famous psychologist discovered that people have paranormal psychic abilities. In Daryl Bem’s laboratory, participants could guess better than chance where an erotic picture was going to appear on their screens, even before the computer randomly decided the location. That is, before something could possibly be known, people seemed to know it—at least, they knew it a tiny bit more often than they would if they were just guessing randomly.

(You might wonder: why did the pictures have to be erotic? Bem didn’t explain, but people’s psi abilities only seemed to work for saucy photos and not neutral ones. Maybe being clairvoyant requires being a little horny.)

If this happened once, we might write it off as a fluke. But Bem’s paper had nine experiments showing various forms of “precognition” and “premonition.” Nine flukes is too many flukes.

This made a lot of psychologists very upset because people are not supposed to have paranormal psychic abilities. Even worse, Bem’s paper was published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the world’s most prestigious journal for those subfields. And we couldn’t dismiss Bem as some random crank—he’s a tenured professor at Cornell, and his self-perception theory is standard reading in intro psych classes. The dude’s legit, and now he’s saying ESP exists, and his paper got through peer review and into one of psychology’s best journals.

This was the first great disaster in the dark period in psychology that would come to be known as “the replication crisis.” The second came later that year, when a team of psychologists showed that, using the same statistical practices everybody else was using, they could make it look like listening to a Beatles song magically made undergrads younger. The third, and worst, came in 2015, when a huge group of social scientists tried to redo 100 psychology studies and less than half of them “replicated,” meaning that instead of producing the results they produced the first time around, the studies produced bupkis.

I started my PhD in 2016, right when things hit rock bottom. I found a bunch of sunken-eyed grad students shuffling around shellshocked, as if their parents had just called and said “we never really loved you, it was all a big prank, goodbye.” Big name professors were barricaded in their offices, writing screeds (since deleted, but preserved here) about how their studies don’t replicate because the replicators are vengeful know-nothings. Online, bloggers and commenters mercilessly bullied one professor because one of her studies didn’t replicate; it got so bad The New York Times wrote about it. At parties, when I would introduce myself as a psychologist, inevitably some dude who had listened to like one podcast about the replication crisis would go “oh, but none of it replicates, right?” and smirk at me like I just revealed I’m a Renaissance Fair actor—that is, I enjoy engaging in a very public and embarrassing form of make-believe.

The sky seemed to be falling, but a few people, including my PhD advisor Dan Gilbert, insisted that the sky was just about where it should be. Nobody believed in ESP or Benjamin Button-ing sophomores, of course (except maybe Daryl Bem), and everybody agreed we should abandon the practices that could make such fantasies seem real. But the “most psychology studies don’t replicate” paper went too far. Dan and his friends pointed out that the results were so noisy that they were consistent with both excellent and terrible replicability. And cherry-picking 100 studies and claiming they can stand in for all of psychology is a bit like claiming you can forecast an election by sauntering down to your local pub and surveying whoever looks friendly. Plus, some of the replications used totally different methods. For instance:

An original study that asked Israelis to imagine the consequences of military service was replicated by asking Americans to imagine the consequences of a honeymoon; an original study that gave younger children the difficult task of locating targets on a large screen was replicated by giving older children the easier task of locating targets on a small screen; an original study that showed how a change in the wording of a charitable appeal sent by mail to Koreans could boost response rates was replicated by sending 771,408 e-mail messages to people all over the world (which produced a response rate of essentially zero in all conditions).

Okay, so some people said some stuff, and other people said some other stuff. What should you think? You could very diligently read the original paper, the reply, the reply to the reply, and the reply to the reply to the reply and the follow up to the reply to the reply to the reply. Or you could just read on, because I’ve got something to say about this that I haven’t heard anyone else say, and it’s been growing fitfully inside me, fighting to burst out of my chest like that alien in Alien.

So here it is, both directed at and dedicated to every smirking guy at every party who was like “oh isn’t all psychology like made up and fake” and I was like “oh well uh actually—” and then someone would burst between us being like “OMIGOD KYLE WHAT’S UP HAVE A SHOT” and suffice it to say we wouldn’t get very far in discussing the intricacies of the replication crisis.

This one’s for you, Kyle.

THE PEN IS BOTH MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD AND EASIER TO PUT IN YOUR MOUTH

So, first of all, when we talk about the replication crisis, we always mix up two things. One is “uh oh, our methods, statistics, and standards of evidence are so shoddy that they allow people to prove that ESP is real.” That’s bad! We should do something about that, and largely, we have. It used to be that you could show up with like 20 participants in a condition like “sup guys I just proved that thinking about soccer hooligans makes you dumber” (it doesn’t). If you tried to do that today, you’d get laughed out of the room. I think that’s great!

But the point that gets mixed in is “now we should go back and double-check every psychology study.” And that, my dear Kyle, makes no sense to me. First of all, have you seen the studies we’re replicating? Here's one:

Computer terms are more accessible than general words after answering a block of hard trivia questions; measured as longer color-naming reaction times in a Modified Stroop Task after priming with computer terms compared to priming with non-computer terms

Here's another:

The original finding was that people experience more mixed emotions when they are reminded that they are at the end of an experience compared to when they are not reminded. We focus on Study 2 (of 2) in the paper, which surveyed college graduates on graduation day. Some graduates were randomly assigned to be reminded that this was their last day as students, while others were not reminded. Then graduates rated the emotions they were feeling.

And another:

Participants will prefer descriptions of the city of Los Angeles that are more concrete/less abstract when they are exposed to the words “Los Angeles” during an earlier exercise. Participants who are not shown “Los Angeles” during this earlier exercise will prefer relatively less concrete/more abstract descriptions of the city of Los Angeles.

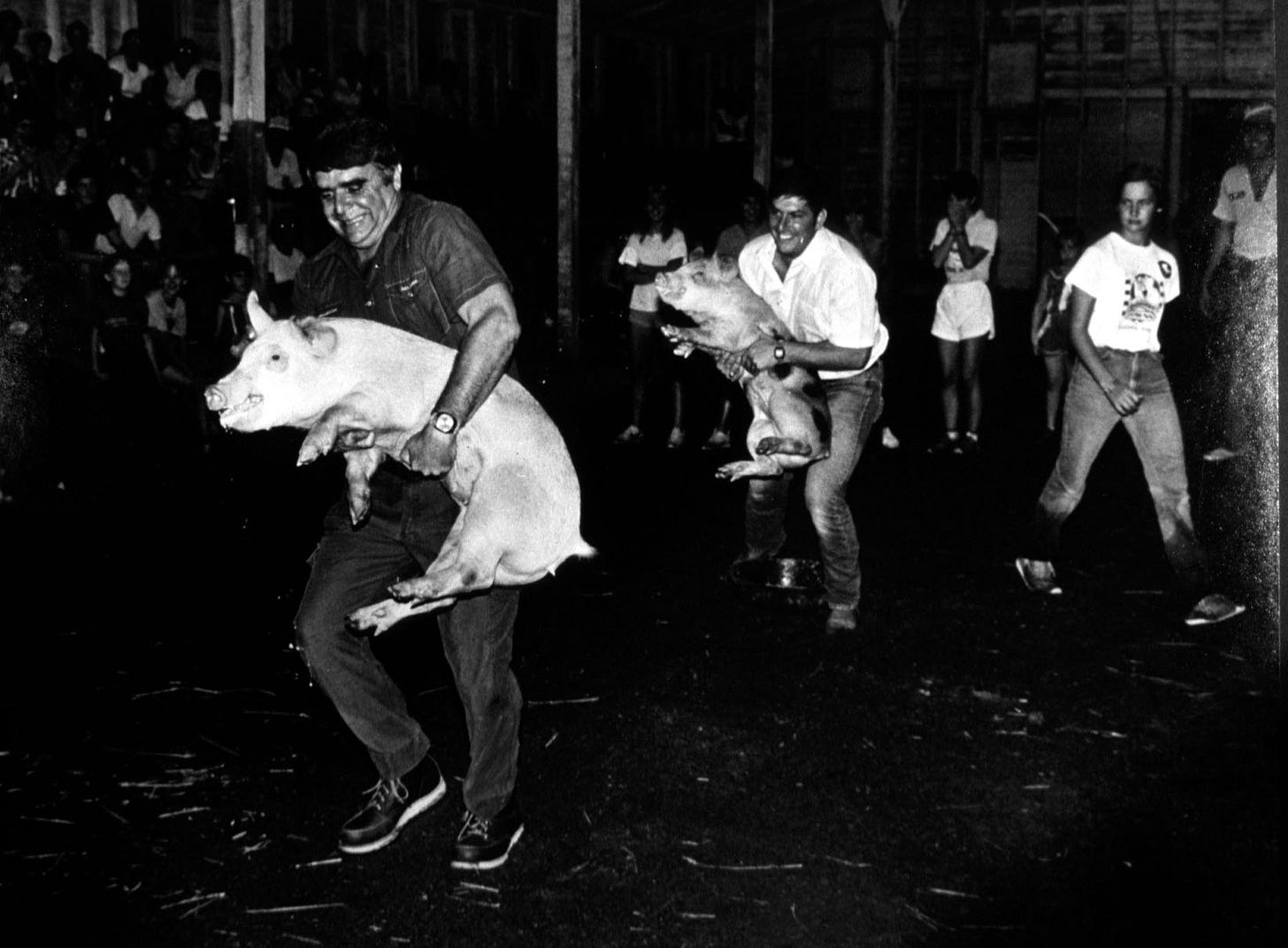

I could keep going; this is just what most studies are like in psychology. One of the highest-profile replication efforts tried to figure out whether drawing a line through lots of “e”s later makes people worse at picking out which digit is different from other digits. (A second big replication attempt later tried to test the same hypothesis in a slightly different way). Another big replication tried to finally settle the question of whether people say jokes are funnier when they hold a pen in with their teeth vs. when they hold a pen with their lips, like this:

These studies fail the experimental history test: they’re either not stories about people, or they don’t make me feel anything, or both. With all respect to the authors and the replicators, I’m just not that worried about what happens after you make people read the words “Los Angeles” or cross out of a bunch of “e”s. Are you, Kyle?

That’s why I’m so confused when people get their britches in a bunch about the “replication crisis.” I understand people’s careers are on the line, and everybody loves watching big-shot professors get pantsed. But if these studies are all that's at stake, why all the wailing and gnashing of teeth (hopefully after removing the pen held between them)? Why the nonstop parade of apocalyptic articles in scientific journals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), as well as popular outlets like The Atlantic (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and The New York Times (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)? Why all the people trying to harsh my vibe at parties? Seriously, Kyle, what’s your angle here?

I have a guess. In fact, I have three guesses. I think you’ve got three big fat myths in your head about how science works. And I don’t just think it’s you, Kyle, and I don’t blame you for it. I think most psychologists and maybe most scientists believe these myths too, because I see a lot of people acting as if they’re true, and I never see anybody trying to dispel them. So I’m gonna do it. Gimme another drink.

BUSTED CASTLES

Okay, here’s something I bet you believe, whether you know it or not. You think that doing science is like building a majestic castle of stone. Every finding, no matter how small, builds the castle taller and stronger. If you believe that, no wonder you’d think it’s a huge problem if some studies don’t replicate—it means the foundation is crumbling and the whole castle might topple over.

I can’t speak for all of science, but psychology doesn’t work like this. There is no grand unifying theory. We have a few local theories, but mostly we have no theory at all. So we don’t have a majestic castle where every stone is stacked on top of another stone; we have a few stone huts and tons of individual stones scattered everywhere. That means trying to replicate psychology studies is a bit like kicking one of those stones, watching it shatter into a million pieces, and going, “Aha! Nothing can be built on this!” But there wasn’t anything built on it.

You can see this for yourself. Take out your phone, pull up a psychology paper, and click on “cited by” (here’s that page for the original pen-in-the-mouth study), where you can see every subsequent paper that cited the one you’re looking at. When you see hundreds or even thousands of papers there, you might assume that means lots of findings are depending on this finding to be true. But they aren’t. When you read a few of those “cited by” papers, you’ll find that virtually all of them would be unchanged if you deleted the paper they’re citing. So even when a paper gots tons of citations, it’s mostly people pointing to a stone, rather than placing their stone on top of it.

That’s certainly true for me. I looked back over the last few papers I published, counted up my citations, and then counted how many of those were critical, meaning my paper would be in big trouble if you took that other paper away. On average, about 15% of my citations were critical, and half of those were citations of statistical software I used.

(You might wonder: why do scientists stuff their papers full of superfluous citations? Fair question, Kyle. Mainly we want to please reviewers. If you’re writing about, for example, “attentional blink,” you can show you’re a good little scientist by citing everything anyone has ever said about attentional blink, regardless of whether it has anything to do what what you’re doing. Besides, some of the people you cite may end up reviewing your paper, and you better believe they’ll be looking for their names.)

Older scientific fields may be more cumulative than psychology, but as Thomas Kuhn pointed out 60 years ago (bet you thought you were gonna get through this party without someone bringing up Kuhn, huh? Too bad!), every field goes through cycles of castle-building and castle-smashing, and many stones don’t survive the smashing. For instance, if you had done your PhD with Galen of Pergamon, you might have done your dissertation on phlegm, or something, because humoral theory said that was a very important thing to study. But then humoral theory got smashed, and now your dissertation is dust. Sorry, pal! That’s science. Another drink, Kyle, I’m just getting started.

THE ADOLESCENT SCIENCE

Here’s the second myth I think is in your head, one I wanna pop like a pimple.

You probably see people earning PhDs, publishing papers, getting jobs, etc., and you’re like “ah, this strongly suggests that something important is happening.” Nope! It really could all be for naught. That’s the problem you get when science gets professionalized—it always looks like everything is very serious and significant, even when it isn’t. Much of science is just people playing the science game: pull a lever, get a result, pull it more times, get a grant, pull it enough and you might get tenure, which earns you the right to keep pulling that lever ’til you die.

Psychology has an additional problem: it’s a young science, and we don’t have a strong sense of what’s important and what’s not. A hundred years ago, a hot theory in our field was that little boys wanna kill their dads and bang their moms. We’re still figuring things out, okay? Like all teenagers, one day we’re really into one thing (wearing all black, listening to The Smiths, studying ego depletion), and the next day we’re onto something else. That means haphazardly replicating psychology studies, like we’ve been doing so far, is a bit like barging into a basement full of teens and shouting “WE MUST KNOW ONCE AND FOR ALL IF DYEING YOUR HAIR BLUE AND SHOPPING AT HOT TOPIC IS ACTUALLY COOL OR IF IT’S TOTALLY LAME” and it’s like, dude, chill out, tomorrow we’ll be dyeing our hair a different color and buying our t-shirts somewhere else, and also how did you get into our basement???

So I think “Do most psychology studies replicate?” is the wrong question. The right question is “Do most psychology studies matter?” and I think the answer is probably not. I know that sounds like criticism—“psychology is so dumb, lol”—but I really mean it as a description. We don’t have a good idea of what matters, and until we figure it out, we’re going to do a lot of weird stuff, and that’s okay.

I’ll accept this description myself: it’s not clear that my own work matters. I think it’s important that conversations don’t end when people want them to, and that people don’t know how public opinion has changed, and that popular culture has become an oligopoly. But if you just don’t care, I don’t have anything objective that will convince you. It’s not like you’ve got your version of physics and I’ve got mine and we can both try to build a bridge and see which one stays up and which one collapses. You really just have to sniff a lot of ideas and get a sense for what a good one smells like. That’s why I did a PhD; I wanted to learn from someone with a good nose.

You might think that numbers and statistics can distinguish the important stuff from the unimportant stuff. They can’t, Kyle! We use statistics to help us figure out what’s true. But plenty of true things aren’t important. “People crash their cars more often when you blindfold them.” “People have a hard time sleeping when you play Insane Clown Posse really loud.” “People like receiving $5 more than they like getting kicked in the head.” I’m sure all of these hypotheses could score you big honkin’ effect sizes. All of them are true. None of them are important.

“If scientific importance is just a matter of opinion, what does it matter?” Now we’re getting somewhere. I really do believe that some things are more important than others in a way that transcends human opinion, even if there’s no objective way of proving it. It’s a religious belief, Kyle, I’ll admit it. But it’s so important to believe in it, to care about it, and to argue for it. (That’s why I wrote “Underrated ideas in psychology.”)

And I think you believe it too, Kyle. You’re a dude in your thirties, so you must think The Sopranos is a better television show than Love Island, though you’d also agree it’s not “objectively” better. Fine, but if we threw up our hands and said “well, there’s no way of objectively telling which art is good” there wouldn’t be any reason to make expensive prestige TV over cheap schlock. And a little cheap schlock is fine, but you and I both want to live in a world where The Sopranos gets made. For that, we need to believe that some things are better than others, even if there are no numbers that can back it up. The same goes for psychology, and for any science: to do the best work, we must believe that some questions matter and some questions don't, even if there’s no objective standard we can use to compare them.

So if you think my ideas stink, that’s all right—I guess don’t stand near me! But for now stay right there Kyle, I’m not done with you.

I REGRET TO INFORM YOU THAT YOU ARE LIVING IN THE DARK AGES

I’ve got one more myth for you, Kyle. One I’m sure you hold deep in your heart but have never spoken aloud.

You think you were born into an era of enlightenment. You think your ancestors suffered under shamans and charlatans, but you enjoy the fruits of centuries of science. I understand this belief. When we got our chemistry textbooks in high school, there weren’t a thousand blank pages in the back labeled “ALL OF THE CHEMISTRY WE HAVE YET TO DISCOVER.” The text went right to the back cover, as if that’s all the chemistry there is and will ever be.

But Kyle, as much as we have learned since Galileo peered through his telescope and Hooke peered through his microscope, we still live in the Dark Ages. Look around you. Physicists don’t know whether cold liquid freezes faster than hot liquid. Sometimes glowing balls of energy just appear out of nowhere and we don’t know why. Being a human feels like something (“consciousness”) and we don’t have any good explanations for this. About 85% of matter in the universe is “hypothetical,” meaning we don’t really know if it exists or not. (These abundant mysteries are one of the reasons I have vowed to fight anyone who thinks ideas are getting harder to find.)

You discover our Dark Ages real quick if you ever have to see a doctor. Does your stomach hurt? You may join over 25 million Americans who are diagnosed with Irritable Bowel Syndrome, which is shorthand for “we don’t know why your stomach hurts.” Do you have cancer? Most of our state-of-the-art cancer treatments boil down to “Doctors try to kill you and you hope the cancer dies before you do.” Do you feel really depressed? Doctors can a) talk to you for a while and see if that does anything, b) give you some pills that might make you feel a little better a month from now (and nobody knows why), or c) electrocute you.

(By the way, all those fancy drugs we have? Most of them don’t work for most people.)

I have flat feet, and they hurt a lot when I was a kid, so I went to a podiatrist, expecting that surely in this age of Science and Reason something could be done about that. He told me they could shatter my ankles and rebuild them and maybe that would get me an extra decade of being able to run. Or he could surgically insert a plug into my ankles, which would have to be replaced every six years. I told him that, on second thought, my feet didn’t hurt so bad.

We live in an age that’s less dark than ever, and yet we still know so little. If you don’t appreciate that, whenever you hear that another scientific finding has failed to replicate, you might feel like you’re being robbed of your birthright. But it was never yours to begin with. Or, if it was, it belongs to every human who ever lived as much as it belongs to you. Billions of humans lived and died in ignorance, and so will you, and so will I. All we can do is try to leave a little less ignorance than we found.

STEALING FIRE

It’s late, Kyle. But I’ve got one last thing I have to say to you.

You know Prometheus, the Greek god who stole fire from his fellow gods and gave it to humanity, allowing them to create civilization? It turns out cultures all over the world have stories like that. Crows, opossums, spiders, tricksters and heroes of all sorts, pilfering fire and handing it over to us mortals. In fact, in these stories, fire seems to be stolen more often than it is given. Why might that be?

Maybe it’s because humans have always realized that Nature never gives up her secrets willingly. Try to explore her jungles and she will send snakes and mosquitoes to stop you. Try to explore her mountains, seas, or skies, and she will deprive you of air. You can’t even try to explore cells and atoms because she made them too small to see. For God’s sake, she made it so that lemons cure scurvy but limes don’t!

So we assemble teams and tools to burgle Nature’s vaults of knowledge. We draw up plans. We recruit specialists. And when the moment is right, we make off with as much knowledge as we can. Every discovery is, in fact, a heist.

The deepest, thickest vault of all is the human mind. Nature guards it with biases and illusions; she seduces us into believing that we can know our own minds through simply inhabiting them. That’s why we’ve made more progress in other scientific fields than we have in psychology. The ancient Greeks invented democracy and calculated pi and built magnificent columns that still stand; they also believed that emotions live in the liver. When NASA launched the first satellites into space, psychologists were still claiming we’d never have any idea what happens inside the human mind, so we shouldn’t even try.

That’s all right—it means we can still pull off the greatest heist of all time. The biggest, shiniest jewel in all of science—why do people do what they do?—is still sitting in Nature’s vault, waiting for us to drill the lock, melt the hinges, blow the door, whatever it takes. I am going to steal that jewel or die trying.

So Kyle, if nothing else, I hope you’ve learned not to question someone’s entire life based on one podcast you listened to. Now if you’ll excuse me, I really gotta pee.

This essay could easily have been a lot more defensive, and I appreciate the nuanced approach of attempting to reckon with the actual situation, rather than presenting a fantastical vision of scientific research. Something that often frustrates me is when people think theories accurately describe reality just because they were uttered by a scientist and peer-reviewed. Psychology, like all fields of science, is an attempt to build useful models with which we can explain or predict certain events and situations. The models are meant to resemble and replicate reality as much as possible, but it is important, I think, to never confuse the model with reality itself!

As a geographer, I can empathize with having my science dismissed. It's hard to explain how important the field of geography is to the uninitiated, because it basically treats all the other sciences like a goodie grab-bag and says "but let's analyze it spatially." Someone I know once asked me "Isn't geography just non-scientific geology?" It is most definitely not. Geography explains the interconnectedness between geology and meteorology and biology and ocean mechanics and crisis management and sociology and politics and yes, psychology. After all, the World Population Review (a bunch of geographers) ranks countries by happiness. And once we know where people are happier, then we can look into why people in different places might be happier, further enriching and informing psychology...

I love geography.

I understand saying we live in the Dark Ages (my dad had to have his jaw broken and re-set to help his TMJ, and a chiropractor once said that if I wanted to aggressively treat my mild scoliosis they could strap me to a table and slowly pull me in two different directions). But I think simultaneously we are also experiencing some enlightenment. Personal boundaries and bodily autonomy have really come into the popular conscious in a way that they weren't, even as recently as when I was a kid. And I think that advancement was built on some pretty big stones in the field of psychology. In other words, we don't know everything, but I think we've learned some pretty nice pieces. Some of these rocks are pretty solid and well-formed.