Reading the news is the new smoking

I quit. I feel great. You can too.

One of my major pastimes used to be reading the news and being mad. I’d wake up, grab my phone, and get a quick primer on all the day’s outrages. “They raised tariffs on soybeans!” I would cry, unsure if the tariffs were bad, or if it was bad that they had waited so long to tariff them, but very sure that something about soybeans and tariffs was definitely outrageous.

During the Trump administration, I would devour news of the president’s latest impropriety and imagine myself throttling one of his supporters. “WHY DID YOU DO THIS??” I would shout, squeezing the life out of them.

I started to feel like maybe this was a bad thing.

So in the summer of 2020, I stopped. I swore to only read the news on Saturday mornings. Since then, I’ve given it up almost entirely.

And I feel better. Way, way better. It feels like a war that used to be fought in my backyard is now being fought on Neptune instead. I feel relieved of my duty to keep track of the whole world, and I now realize I never had that duty in the first place. My brain got quieter and I started hearing myself think instead of hearing myself worry. And I stopped imagining myself choking people to death, which was a big improvement.

I also became more fun to be around. I stopped importing my grand anxieties into conversations with friends, punishing them with my sullenness because I just read an article about climate change or bad senators, as if nobody was allowed to feel good as long as bad things are happening. I lost the urge to extract my phone from my pocket during lulls in conversations, tap the News app, and see if maybe something awful had happened. I could fill my freed-up attention-space with more important things, like my niece and nephews’ various misadventures.

That’s how I came to see reading the news like smoking: harmful not just to the consumer, but to anyone nearby. People used to think smoking was a fine way to start the day, a reasonable thing to do on a break, and even a healthy part of their routine—“More Doctors Smoke Camels!”—just like they think about reading the news today. People used to reach for cigarettes when they felt stressed or bored; now they reach for CNN. Some people couldn’t even get out of bed without a smoke, while today some people can’t get up without checking the news first.

I can’t promise that quitting the news is just as good for your lifespan as quitting cigs, but it is way easier, and people who do it universally report positive results. The Surgeon General is unlikely to issue a warning label for the news anytime soon, so here’s mine.

Why I don’t smoke the news

It makes me feel terrible

A pretty good rule of thumb is “don’t do things that make you feel terrible unless you have a very good reason.” I feel terrible when I read the news, because all the headlines are things like “Republicans Vote to Reclassify Plastic as a Vegetable“ or “Birder Murderer Murders Thirty-Third Birder" or “Bradley Cooper Calls Holocaust ‘Big Misunderstanding’”. Sure enough: studies show that reading the news makes people feel bad.

The news often makes me feel even worse than bad: it makes me feel bloodthirsty. I read about Congress doing something and my brain goes “smite them, slice them, burn them, bury them!!” And I’m not alone. I’ve seen mild-mannered moms swear they would kill certain politicians with their bare hands if they had the chance. I’ve seen Christians pray for Supreme Court justices to suffer heart attacks. I’ve heard nebbishy grad students wonder aloud whether assassination is such a bad thing. I’m not saying the news is solely responsible for this, but it sure doesn’t help.

I would reluctantly keep reading about bad stuff if that somehow made it go away. But no matter how much I read, bad stuff keeps coming. Which makes sense, because it’s not like the news actually led me to do anything about the bad stuff. It kind of felt like my big contribution to the cause was reading and feeling bad. It was like I was floating above all the victims of every bad thing, going “Don’t worry everybody, I’m here to read all about you and feel awful!”

The news screws with my perception of the world

Villainy is rare in the world but common in the news, so reading it may fool you into thinking you’re surrounded by evil-doers. But you’re not.

As part of a research project, I once looked at two weeks of New York Times front pages and color-coded all of the stories based on whether they were about people being bad (red), good (green), or neither (gray). It turns out the newspaper is black, white, and red all over:

With all this coverage of people’s misdeeds, it’s no wonder that people think crime is going up even when it’s going down:

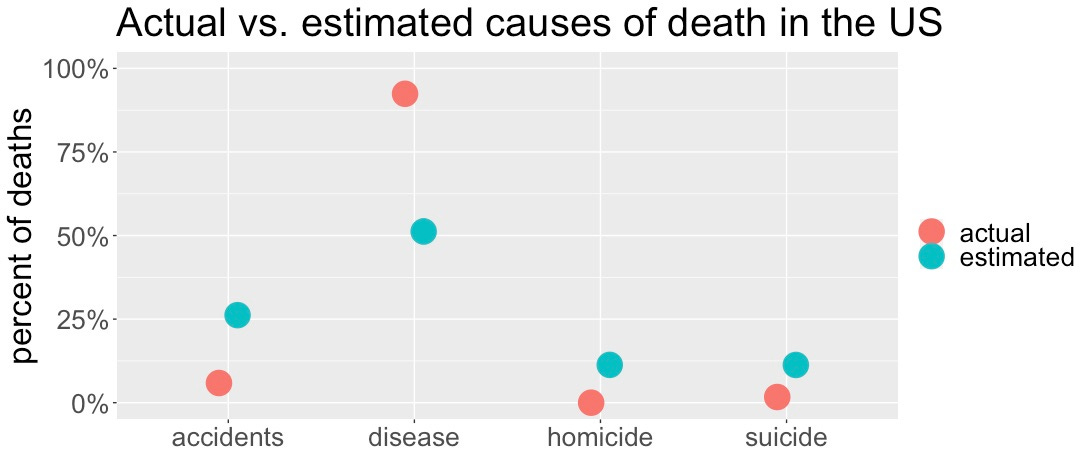

In fact, in another of my research projects, people drastically overestimate the percentage of Americans who die by homicide, suicide, and accidents, maybe because these kinds of deaths tend to generate news stories while dying from heart disease does not:

This leads us to fear things that probably won’t kill us, like nuclear power plants, and not fear things that probably will kill us, like coal-fired power plants. (Even accounting for high-profile, news-generating accidents, nuclear energy is so much safer than coal that you can barely see both of them on the same graph.)

Plus, as Gwern Branwen points out, as population and media coverage increase, “anything that can happen will happen a small but nonzero amount of times” and we’ll no doubt hear about it. In a world of eight billion people, “crazy person does crazy thing” is not news; it’s an inevitability.

Most of the things in the news only seem important because they’re happening today

When I drastically cut back on my news consumption, I realized that all of the seemingly world-changing events from the previous week had, in fact, not changed the world at all. Scandals go supernova and dissipate in days. People are mad about one thing, then they’re mad about another thing. There was only one story that actually seemed to matter from week to week—“a pandemic is happening!”—and I already knew that one.

My favorite example of this is a piece of performance art my friend strung together during the Trump administration: a 167-tweet thread that was simply a link to each new Trump outrage with the caption, “This will be the thing that finally brings Trump down.” Spoiler: it wasn’t.

The news is another thing to check and checking is a waste of time

There’s always something new when you check the news (not a terrible slogan!), which makes checking seem like it’s going to be interesting, but then it turns out it’s the same junk as always.

I bamboozle myself the exact same way with my email. Every time my inbox dings, my brain goes “OOOH BABY GOTTA CHECK OUT THIS EXCITING NEW EMAIL” and 99% of the time the email is something like “Hi we’re Dunkin’ Donuts and we have donuts!” I have probably wasted 30% of my life so far on pointless checking like this. And checking the news is especially bad—much like checking your stocks, it’s stressful, misleading, and encourages you to act rashly.

A concerning amount of stuff in the news is flat-out wrong

Last year I wrote a scientific paper that got lots of media attention, and I was amazed at how many articles misstated basic facts. For example, this article originally claimed our study was about phone conversations—it wasn’t, all the conversations we studied were face-to-face. They changed the headline when I wrote to them about it, but the rest of the article still heavily implies that participants were on Zoom or on the phone. If I can see the news getting it wrong when I happen to know the right answer, why should I rely on them anywhere else? (Michael Crichton had a term for forgetting this realization: Gell-Man Amnesia.)

Unfortunately, my story seems to be pretty common: in one big study, 61% of articles contained factual errors, as judged by people with firsthand knowledge of the event being covered. News is, after all, the first draft of history, and first drafts usually suck. I’m happy to wait for something a little more finalized.

I can spend time doing other stuff

If you spend 30 minutes reading the news every day from your 18th birthday until your 90th, you’ll spend 547.5 days on the news alone. I think we’ve all got better ways to spend a year and a half.

For me, I’m always finding new weird and wonderful blogs to read—The Classical Futurist (good post) and Maia Mindel’s Some Unpleasant Math (good post) are two I picked up recently and really enjoy. I subscribe to The Browser, which curates stories from all over the internet. And then I read books, which are like the internet, but printed out and stapled together. They’re also kind of different in that nobody yells at you while you read them.

More importantly, I close my laptop and do other stuff. I hang out with my friends. I do Pilates. I go outside and stand near trees. It’s great!

But what about…?

When I tell people I stopped reading the news, sometimes they act as if I’ve just told them that I heat my home by burning big piles of crucifixes. I get it: I seem like I’m sticking my head in the sand. For instance:

But to me, people who read the news seem like they’re sticking their heads in sewage. So we have some misunderstandings to clear up. Here are a few of the arguments I’ve gotten, and why I don’t find them convincing.

(May I also interest you in other people’s arguments about not reading the news, like this one from Applied Divinity Studies or this one from Aaron Schwartz or this one from Rolf Dobelli.)

“You have to be informed.”

Probably the greatest PR victory of all time is news media convincing people that “being informed” = “reading the news.” To be an informed person, you should know things like what causes headaches, where to get cheap good food, whether your deodorant will give you armpit cancer, and a billion other things. The news is a pretty inefficient and misleading way to get there, especially because understanding the world requires you to know a lot of things that happened long before today, which is exactly what the news doesn’t cover. If you’re going to read the newspaper, you might learn more reading an issue from 1971.

Media types will own up to this when nobody’s looking. I was once at a dinner with an editor at a big-name news organization, and after he put back a few drinks, he looked around at us, wild-eyed. “Some people think we’re, like, doing public service,” he said. “We’re not. This is entertainment for people who want to feel smart.”

“Democracy dies in the darkness!”

It seems like a good idea to have the news so that we know when bad things are happening and can act appropriately, right?

Fire alarms also seem like a great idea: when there’s a fire, play a big loud noise so everybody knows they should evacuate. This works great when the alarm only goes off in response to fire and otherwise says quiet. But when fire alarms go off in response to nothing at all, what do we learn to do? We plug our ears and wait for it to stop. That’s what tragically killed 19 people in the Bronx earlier this year:

Smoke alarms were located throughout the building, but several residents said they were used to hearing false alarms and initially didn't think anything of it. It wasn't until some residents saw smoke and heard cries for help that they realized this wasn't a false alarm.

"So many of us were used to hearing that fire alarm go off, it was like second nature to us," said resident Karen Dejesus.

Even a tiny bit of overuse can render a warning system totally useless, and that’s exactly what’s happened to the news. There are so many crises and scandals and tragedies that it’s hard to take any of them seriously. News becomes noise.

So yes, democracy dies in the darkness. But democracy reacts to sunlight the same way humans do: a moderate dose keeps it healthy, but too much turns it blind and cancerous. Indeed, the news helped Trump metastasize, lavishing him with $2 billion of free coverage during the primary alone.

“If you don’t read the news you’ll be left out of conversations.”

That’s fine by me, because those conversations are usually like:

“Did you hear about this outrageous thing?”

“Yes!”

“It’s so outrageous!”

“It is!”

“I’m mad about it!”

“Me too!”

“It’s just like them, to be so outrageous!”

“What do you expect!”

“These times, huh?”

“Tell me about it.”

These conversations make me uncomfortable because if we were really so outraged, we should be doing something about it, rather than just talking about it. It’s a lot like standing around saying:

“Do you smell this terrible smell?”

“Yes!”

“It’s so smelly!”

“It is!”

“I’m mad about it!”

“Me too!”

“It’s just like this smell, to be so smelly!”

“What do you expect!”

“These smells, huh?”

“Tell me about it.”

“You should read the news and feel bad! The world is full of suffering and you should pay attention to it!”

I used to gulp down articles about genocide, pestilence, and hunger—and do precisely nothing about them. That’s voyeurism, not virtue. If I actually want to empathize with people who are suffering, I should read something written by them, or at least something written with care and depth, not something simply fired off to feed the 24-hour titillation machine.

But I agree with this argument’s sentiment: the world is full of bad things and you should do something about them. The news is just a bad way of figuring out what the bad things are and what to do about them. I am a son, a brother, an uncle, a partner, and a friend; I make my living teaching students and doing research. I actually matter in those small circles, and I understand what the problems are and what to do about them. I can literally change lives by trying to do good in my corner of the world, and reading the news distracts me from that.

“Sometimes good things happen because people read the news and get outraged about stuff and demand change.”

Outrage is like mustard gas: you can decimate your enemies with it, but it often harms innocent people and it blows back at you, too. Plus, if you use it against your enemies, you can bet they’ll use it against you. Pretty much everyone has agreed that mustard gas is so terrible that it shouldn’t be part of our conflicts, even when we’re willing to kill each other in other ways. I wish we could do the same with outrage: acknowledge that it’s a weapon of mass destruction and mutually disarm. In the meantime, I can at least refuse to lob canisters of outrage at my enemies and avoid breathing in the outrage they fire back.

“Some news is actually informative.”

“The news” unfortunately lumps together a bunch of stuff, and not all of it is bad for you. Longform, in-depth journalism like this story about the Silk Road and Dread Pirate Roberts is often good and deserves a different name, like “short nonfiction.” (Notice it’s not really news—it came out long after the events happened.) I don’t know what you would call stuff like this firsthand account from a Ukrainian professor during the war, but it’s also great. Local news is sometimes useful because it can tell you, for example, whether a bridge you were planning to use later has collapsed.

Unfortunately, most major news providers mix these breaths of fresh air into a big thick cloud of poisonous smoke. Fortunately, the best stuff tends to make it out whether or not you check the news: I saw that Wired story on Twitter, and I got that Ukrainian story from The Browser. So you don’t have to go hacking and wheezing through the news to find good stuff. It’ll waft over to you eventually.

“What would you do if there was a nuclear missile on its way?”

I guess I would die like everybody else, though I think I would notice the running and the screaming. It turns out that you hear about truly important developments eventually—like “you now have to wear a mask inside stores”—whether you read the news or not.

But I understand the idea behind this question: aren’t some things so important you should know about them right away?

I think this is a trap. I broke my news rule just once, during the uprising on January 6, 2021. I immediately regretted it. What was I going to do, pick up a gun and rush to the defense of democracy? Instead, I did what everybody else did:

“It’s so outrageous!”

“It is!”

“I’m mad about it!”

“Me too!”

How to garden a mind

Cultivating a garden is all about keeping some stuff out (bunnies, birds, bugs) and keeping other things in (water, fertilizer, sunlight). You can’t grow anything directly; you don’t make sunflowers taller by yanking on their stalks. All you can do is create the right environment and hope the seedlings reach for the sky.

Cultivating a human mind works the same way. You have to keep some stuff out (lies, noise, fear) and some stuff in (knowledge, experience, love). You can’t grow your mind directly; you don’t get smarter by yanking on your frontal lobe. All you can do is create the right environment and hope your brain-folds get deeper.

When it comes to mind-gardening, I think the keeping-in comes easy and the keeping-out comes hard. Our ancestors never had more videos than they could ever watch or more books than they could ever read. We, their hapless descendants, are evolutionarily unprepared for a world where we can binge on content until we hurl. We need the mental equivalent of chicken-wire: a barrier to let the sunlight in while keeping the varmints out. For now, that barrier must come from deliberate practice. But perhaps one day it can come from a cultural distaste for the mind-rot of news.

So I hope that news-reading goes the same way as smoking: a gross thing that our grandparents did because they didn’t know any better. Maybe one day people will only be allowed to read the news in designated zones, lest anyone else catch a whiff of any second-hand news. Perhaps rebellious teens will experiment with illicit news-reading, passing a copy of The Wall Street Journal back and forth under the bleachers. Maybe partygoers will step out on the balcony to share a few sinful minutes of “The Daily.” Maybe newspapers will have to carry big warning labels, like a picture of a woman tearing out her hair, captioned with “READING THE NEWS MAKES YOU FEEL BAD FOR NO REASON.”

When people stopped smoking, toxic clouds disappeared from indoor spaces like bars, restaurants, and offices. I think something similar would happen if people stopped reading the news, except the detoxified indoor spaces would be our own heads. People would feel lighter—worries about the fate of the world tend to be pretty heavy. Maybe they’d stop feeling like there’s a war they can win if they just scroll far enough. And maybe they’d start looking around them to see how they could actually help.

I think that future sounds nice. If you like to join me in it, I’ll be outside, standing next to a tree.

There ought to be a distinction made between (inter)national and local news. I am a former journalist at a tiny-town paper, where nobody would know who was running for office or how to hold school administers accountable if we had not existed. Unfortunately, these local papers are the first to go out of business, leaving communities further disengaged and uninformed. Local news is a critical fabric of fading civic life.

Extremely good point. On September 11th 2001, I was a very busy mom of a 6 month old baby and 2 year old, at home on mat leave (sorry, Americans), and was very busy momming. It was early evening when a friend called me, and hearing my cheerful 'oh hi, Elisa!' said 'you haven't heard, have you?'

I then turned on the radio, because I didn't own a TV, still don't. Which means I didn't experience half as much 2ary trauma as did the people I know who watched this tragedy play out all day, on repeat, and saw images they will never be able to remove from their brains.

Did my not 'witnessing' this make a difference to the world, and did everyone else I know witnessing it on TV make a difference? Neither did. Did it make a difference to me and my kids that I wasn't 'up to date' at all moments? Absolutely.

With my patients (I'm as psychologist) I use the suggestion of 'harm reduction' - as we do for alcoholics and heroin users who really really can't quit. Perhaps have a 15 minute period once a day to 'catch up', but no more, and only 15 minutes more to have the 'isn't it terrible?' convos with other people. Then try to move that to every second day .....

I also suggest some form of personal activism or effective altruism, so that people know they are actually doing something about the terrible stuff, as well as the way the live their own lives, do their own work, raise their own kids, spend their own money etc.