Here's a graph that strikes fear into the hearts of social scientists everywhere:

Which is to say: Democrats and Republicans do not like each other, and that dislike has only increased for the past thirty years.

People are more than worried about this; they are apocalyptic. For instance, here’s Bill Gates:

I admit that political polarization may bring it all to an end, we're going to have a hung election and a civil war.

Scientists are sounding the alarm, too, in a nonstop spray of scientific articles like this one:

Political polarization entails quite serious risks; political debates get bitter, and the very existence of a civil society may be threatened.

Even activists who witnessed the racist violence of the Jim Crow South think we’re hurtling toward something even worse today:

We're so hate-filled that I'm just afraid that there's going to be some type of battle. That's a strong word, and I don't know a softer word.

With all due respect, I think there’s been a big misunderstanding. The story behind that graph is both less alarming and more interesting than anybody seems to understand, or is willing to admit. So I’m gonna try to tell it the way I think it actually goes.

HURT WITHOUT HATE

Whenever people tell the tale of rising political hatred, they usually start out like this Atlantic article does:

Fifty years ago, out-group hatred in the United States primarily involved race and religion: Protestants against Catholics, Christians against Jews, and, of course, white people against Black people. Most Americans did not care whether their children married someone from a different political party, but they were horrified to learn that their child was planning to “marry out.”

…and today, the story continues, that hatred has shifted from race and religion to politics.

This all sounds obviously true, but lurking in there is one big misconception and one flat-out falsehood.

First, the misconception: of course parents didn’t care fifty years ago about their kids marrying someone from the other party—those parties weren’t that different from each other. You can see this in the figure below, which tracks how often Democrats and Republican House members have voted with each other since 1949. Thicker lines between dots means those dots are more likely to vote the same way:

There were still plenty of disagreements fifty years ago, but they didn’t map neatly onto party lines. You could, for instance, find Republicans who supported abortion and Democrats who opposed it, and members of both parties who supported or opposed the Vietnam War. Since then, everybody sorted themselves and the parties split apart like a cell undergoing mitosis. So it’s not necessarily that people used to be more politically open-minded; it’s that everyone you dislike is now conveniently seated on one side of the aisle.

Next, the flat-out falsehood: fifty years ago, Protestants did not hate Catholics, Christians did not hate Jews, nor did white people hate Black people. I can show you this using the same data that people use to show that Republicans and Democrats hate each other:

All of those lines are well above 50, meaning that Protestants, Christians, and white people say they feel more warm than cold toward Catholics, Jews, and Black people, respectively. In fact, they only feel slightly less warm toward those groups than they do toward their own political party. And that hasn’t changed much since the 1970s.

That may surprise you, because it certainly seems like those majority groups treat those minority groups better today than they used to. And that’s exactly the point: you can treat people badly without hating them. For example, some people think that women are silly little creatures who need to be protected and guided by men—we call that benevolent sexism—and those people will tell you they love women. They just hate it when women do things like ask to be treated as equals. Similarly, 65% (!) of white people in 1990 said they would oppose a close relative marrying a Black person. That’s fallen to 13% today, with very little change in how white people say they feel toward Black people.

How can you claim to like a group of people but also deny them equal rights or get creeped out by the idea of your child marrying them? I think the answer is: man, people are complicated.

Here's one small example. I like animals. Oink oink, moo moo, cluck cluck, it’s all great. And yet I happily pay people to slit animals’ throats, tear off their skin, filet their muscle tissue, shrink-wrap it, and put it in a little styrofoam container for me so I can take it home, cook it, and put it in my mouth. That sounds like the kind of sick thing you would only do if you despised animals and wanted them to suffer and die. But I don’t. I just like eating hamburgers, and I was born into a culture where everybody said all of this is cool, and I just kind of feel like my desire to eat animals matters more than their desire to not be eaten. I’m not hateful; I’m complicated. (And I’m impatient for lab-grown meat.)

HATE WITHOUT HURT

If you can have mistreatment without hatred, can you also have hatred without mistreatment?

I think the answer is yes, and we’re living it right now. For a country where there are supposedly “millions" of people "willing to undertake, support, or excuse political violence,” the actual amount of political violence is pretty darn low, and it hasn’t increased.

There’s no good statistics on how often, say, a Democrat pops a Republican right in the mouth for saying something conservative, or how often a conservative slashes a liberal’s tires for being liberal. One place that shows up is in hate crime statistics. Political ideology isn’t one of the protected categories that can get a regular crime labeled as a hate crime, but the other categories—race, religion, national origin, etc.—can obviously get mixed up in political hatred. Most headlines will tell you that hate crimes have increased in recent years, but what they won’t mention is that’s only true for reported hate crimes. Total hate crimes seem to have fallen, meaning that what looks like an increase in hate crimes may in fact be an increase in reporting.

Big-ticket political violence—shootings, bombings, and the like—gets counted as terrorism, and there were more terrorist attacks in the 1970s, when supposedly people with different politics got along, than there were the 2010s, especially when you account for the fact that the United States added 130 million people in the meantime. Few people remember the 159 plane hijackings that occurred between 1961 and 1972, or that white supremacists murdered a Jewish talk show host in 1984, or that the Earth Liberation Front burned down a bunch of car dealerships and university buildings in the early 2000s. If you’ve got a short memory for tragedies, it’ll always seem like we live in uniquely tragic times.

(Fortunately, these attacks rarely hurt people. Indeed, from 1999 to 2020, you were almost twice as likely to die from falling off your chair as you were to perish in a terrorist attack. If you exclude 9/11, leprosy is more lethal than terrorism.)

So there’s pretty good evidence that people’s increasing tendency to shake their fists at their political opponents has not coincided with an increased tendency to swing their fists at their political opponents. Of course, violence is a high bar. Hasn’t the rise of political antipathy led to an explosion of incivility and bickering? Hasn’t it shattered friendships and hardened our ideological bubbles? Hasn’t it made people willing to discriminate against the other side?

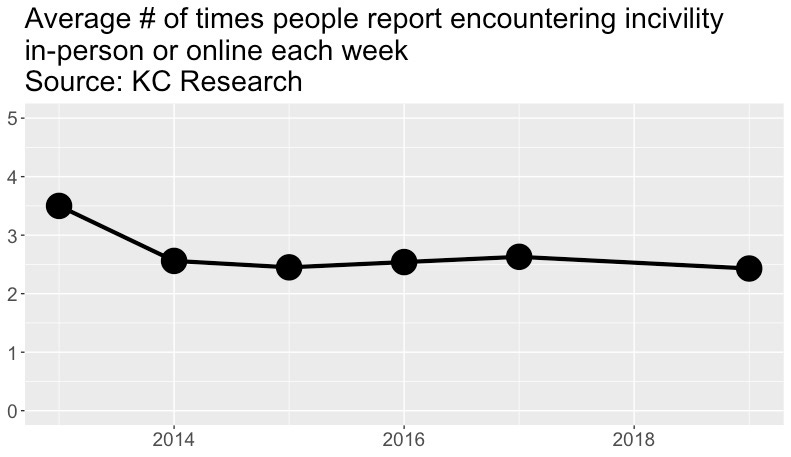

Not really. Let’s take these claims one by one. First, people actually report encountering incivility slightly less often today than they did about ten years ago:

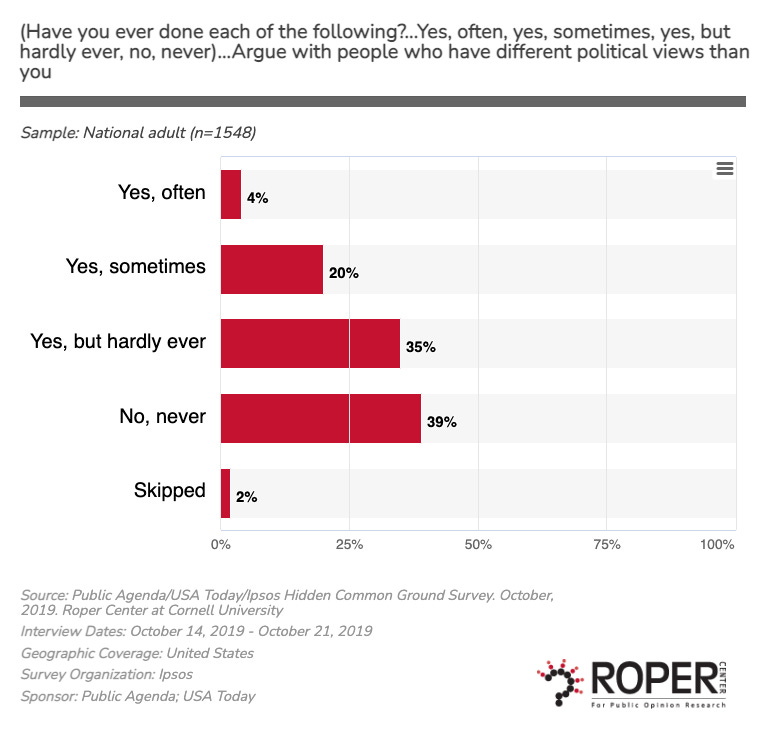

What about partisan bickering? I can’t find data on change over time, but currently about 75% of Americans say they “never” or “hardly ever” fight about politics, which seems pretty good to me:

Maybe we’ve become so ideologically sorted that we just never talk to someone who disagrees with us? That doesn’t seem to be the case, either. About 15% of people do report ending a friendship over politics—not zero, but not much. And most people still report having at least some friends from the opposite party:

How about discrimination? If Democrats and Republicans hate each other so much, they definitely would not want to, say, hire someone from the opposite party. And that’s exactly what researchers expected to find when they applied to jobs in the very liberal Alameda County, California, and the very conservative Collin County, Texas, using resumes that included obvious clues about applicants’ politics (i.e., volunteering for the Romney campaign or being part of the College Democrats). Liberal resumes did better in California and conservative resumes did better in Texas, but the difference was so tiny—just a few percentage points—that the authors had to do some creative statistics to claim there was any difference at all. That is, even when someone could easily discriminate against their political opponents without any consequences, they almost never did it. That’s terrific news!

(Also, why has voter turnout barely budged during these years of growing animosity? If you think the other side is a bunch of depraved monsters who literally deserve to die, wouldn’t you take twenty minutes to vote against them?)

So what about those “millions” of Americans who are “willing to undertake, support, or excuse political violence”? They are likely a mirage created by bad survey design. When you make the questions more specific, give people reasonable response options (instead of giving four options that say “violence is good” and one option that says “violence is not good”), and exclude people who aren’t paying attention, the proportion of people who say that political violence is justified drops to a few percent. And even that number is questionable, because it’s impossible to eliminate every troll and disengaged participant from your dataset. (Scott Alexander calls this “The Lizardman Constant.”)

Look, I’m not saying that partisan antipathy doesn’t matter at all, or that people never hurt each other over politics, or that everything is hunky-dory in the great ol’ US of A. But this data is totally at odds with the story about political hatred that you’ll hear from journalists and social scientists. I think it’s downright irresponsible to go around writing articles that conclude like this:

The only problem is that America’s political partisans may already hate one another too much to take the steps necessary to avoid catastrophe.

A BRIEF DISCOURSE ABOUT JANUARY 6TH

Okay, but what about the January 6th insurrection? Isn’t that proof of political animosity spilling over into violence?

I think it’s actually the perfect example of how we’ve gotten the story all wrong. If you think January 6th happened because the right hates the left, you have a hard time explaining why the rioters tried to bomb the headquarters of both the Democratic and Republican National Conventions, or why they were calling for Mike Pence’s head. You’d also find it a bit surprising that almost nobody supported the Capitol-stormers:

This is America, land of the free and home of the lunatic fringe. People have been raving about the Illuminati since the 1790s. Sometimes the wackos gain political footholds, like the Anti-Masonic Party, which thought the Freemasons were secretly trying to take over the world, or the Know-Nothing Party, which thought the same about Catholics, or the Hard Hats, who beat up a bunch of anti-war protestors and then Nixon appointed their leader as Secretary of Labor. Right now we have a very prominent political figure who is willing to court the nutjobs for political gain. That’s bad, but it’s not new.

If you don’t understand that, you’ll waste a lot of time trying to solve the wrong problem. Some social scientists suggest we could avoid incidents like January 6th through reducing partisan animosity, which we can do by “highlighting commonalities” and “building dialogue skills” and hosting “book clubs.” Ask yourself how many book clubs it would take to stop this guy:

If lowering the political temperature won’t keep the crazies and cranks from storming the Capitol, what will? Maybe listen to people when they say “hey looks like people are going to storm the Capitol” and have a better plan than “we hope nobody ever tries to storm the Capitol.” But the deranged and demented are a permanent fixture in our country, and, as Robert Todd Lincoln said, “As things go in this life it is impossible to thoroughly guard against these classes of people.” He should know—he personally witnessed three presidential assassinations. I’d only add: fortunately, the unhinged and unstable are far rarer than most people think.

HOW MUCH SHOULD WE HATE EACH OTHER?

One last thought.

For all of our handwringing about political hatred, I’ve never heard anyone say what the right amount of animosity is. We all agree that it’s increased over the past fifty years, but was it at the right level before? Should we hate each other even less than that? Or somewhere in between?

Some people seem to think the right amount is zero, or as close as we can get. I disagree. We’re a big, diverse country with lots of opinions packed inside it, and some of those opinions are pretty awful. I don’t think we should aspire to hug white supremacists, or play baseball with Holocaust-deniers, or have dinner parties with people who think it’s cool to shoot up pizza parlors in search of imaginary pedophiles. Nor am I rarin’ to hang out with people who are sympathetic to that crowd. I’m happy to cultivate a healthy dislike for them; it helps keep their ranks thin.

I’m not even convinced that we govern ourselves better when we all get along. Remember that amidst our post-9/11 outpouring of political brotherhood, every single person in Congress (except Barbara Lee) voted to authorize the invasion of Afghanistan, which ultimately became the longest war in American history and killed hundreds of thousands of people, including over 70,000 Afghan and Pakistani civilians. It also cost $2.3 trillion, and at the end of it all, the Taliban is back in charge. That one fateful vote continues to allow secret military action all over the world. (Two years later, the invasion of Iraq also garnered plenty of votes.) Political agreement does not guarantee wise decision-making.

So I don’t know how much animus we need, but we certainly need some. A pinch, a dollop, a dash. Enough to make us think twice about invading two countries in two years.

All that said, I think there is one very good reason to cap our political hatred: it makes us miserable. Not because we’re always coming to blows with our political enemies—the data suggests that doesn’t happen very often—but because we’re always thinking about them. I’ve seen perfectly nice evenings turned dismal by the discussion of the latest political outrage. I’ve heard goodhearted people pine for the painful deaths of certain Supreme Court justices. I’ve watched friends pickle their brains in the poisonous brine of political Twitter. The true cost of partisan antipathy is not the war waged between us and our enemies, but the war we fight in our own heads.

(May I recommend not reading the news?)

I just think this a bad way to live. Indulge your contempt long enough and it’ll turn you stupid and mean. You’ll start thinking that pointless things are actually important, liking writing angry emails to your cousin or publishing the ten millionth scientific article on political polarization. You’ll live in the perpetual hell of a world that is always ending but never ends. I dunno man, maybe join a book club instead.

It seems like maybe the actual story here is, “yet another alarming narrative advanced by ostensibly reputable sources is not nearly as alarming as it sounds “

Thank you for uncovering all these problems with reporting. Personally I try to keep my animosity for "the other side" low, because I think treating others with disrespect only serves to further entrench them in their mindset. Or perhaps a better way to put that is that I try to treat people with respect whether or not I respect their opinion. Respect is both a feeling and an action, after all, and keeping that straight is extremely valuable. And it is so true that hate hurts the hater more than the hated. Great post!