Things could be better

Eight studies reveal a (possibly universal) bias in human imagination

Some scientists get their ideas while beholding the wonders of the cosmos. Some scientists get their ideas while cutting their way through the Amazon with a machete. I get my scientific ideas while eating omelets with my friend Ethan.

One day we were at the diner, trying to figure out why some things seem good and other things seem bad. For instance, why do people hate Congress and love their phones? Obviously the answer is “Congress is bad and my phone is good,” but what’s actually happening in people’s heads when they say that? If you ask a psychologist to explain how this works, they’ll give you a blank stare.

We figured that judgments must be built on comparisons: to say that something is bad is really to say that it’s worse than something else. The thing you compare it to is just whatever pops into your head, even if it doesn’t exist, or can’t exist. Basically, if you can easily imagine something being better, then it must not be very good. So Congress seems bad because it’s easy to imagine how Congress could be way better—for starters, it could have fewer villains. But phones seem great because it’s hard to imagine huge improvements—even if their batteries lasted much longer, for instance, it wouldn’t change phones from terrible to amazing.

If the mind works like that, it would make a ton of sense. It would also explain why people get really mad about things they can’t actually change, but they can easily imagine being better, like Congress, or the threat of nuclear war, or traffic. We thought that would be a pretty neat thing to discover, so we finished our omelets and started running studies.

And we were totally wrong. Instead, we discovered something weirder. We keep seeing it over and over again, and we can’t figure out how to make it go away. Today, I’m here to tell you all about it.

It goes like this: when people imagine how things could be different, they almost always imagine how things could be better.

I’m going to show you eight studies (plus a bonus study) documenting this effect and trying to figure out why it happens and what it means. The phenomenon appears to be incredibly robust. It doesn't depend on the wording of the question, what we ask about, the kind of people we ask, or the language we ask the question in. We think it might offer a peek into human nature, and it may explain why it’s so hard for people to get happier.

This is a real scientific paper, except you don’t have to pay a million dollars to access it. You can get all the data, code, materials, and preregistrations here. (That includes the wording of every question and everything else you need the replicate every study.) And you can cite this project like this:

Mastroianni, AM & Ludwin-Peery, EJ. (2022). Things could be better. https://psyarxiv.com/2uxwk

Now for the science.

PARTICIPANTS

Most participants came from either Amazon Mechanical Turk or Prolific, which are sites where you can sign up to take studies for money. Study 7 participants were recruited for us by a company called Qualtrics. Everybody earned $1-$1.20 and the studies took a few minutes. We included lots of attention checks and tossed out anyone who didn't pass them, but we still paid them regardless.

STUDY 0: WHAT’S ON YOUR MIND?

We wanted to ask people to imagine how a bunch of things could be different, but we didn’t want to pick the things ourselves, since that might bias the results. So we started this project by getting 91 people to list things they think about or interact with on a regular basis. We kept all the items that were listed by six or more people, except for a few items we thought wouldn’t be relevant to everybody. For instance, we dropped “girlfriend” because we figured not everybody has a girlfriend. That left us with 52 items like “your phone” and “people” and “the economy.”

STUDY 1: HOW COULD THINGS BE DIFFERENT?

We got another group of 243 people, showed each person six random items from our list, and asked people how those things could be different. For example, you might be asked: “How could YouTube be different?" while your friend might be asked “How could food be different?". You might say “YouTube could load faster” and your friend might say “food could be more expensive” or whatever.

Then we asked people, “If [THING] was different in this way, how much better or worse would it be?” People gave a rating on a scale from -3 (much worse) to 0 (neither better nor worse) to 3 (much better). What we wanted to know was: when asked how something could be different, do people on average imagine how it could be better, worse, or neither?

The answer was shockingly clear: people imagined how things could be better. Here are some examples.

Us: “How could your phone be different?”

Participants:

“it could be waterproof”

“My phone could be bendable and flexible.”

“Brighter screen”

Us: “How could your life be different?”

Participants:

“I could be rich”

“Have more money”

“I could be more wealthy so I wouldn't have to worry about finances so much”

Us: “How could YouTube be different?

Participants:

“It could stop nagging me about trying their premium service every time I go to watch a video.”

“No ads”

“Fixing the algorithm to not screw over creators”

This happened for every single item. In the chart below, items above the dotted red line were items that people imagined could be better, on average. Every dot is floating above that line, and none of the confidence intervals include zero.

People even told us how good things could be better. We had people rate how good each thing is right now, and “pets” got the highest rating. People loved pets more than “vacations,” more than “friends,” more than “happiness” and “love”! And yet—

Us: “How could pets be different?”

Participants:

“Be patient when it comes to food”

“Healthier/less likely to get sick”

“It would be cool if they could talk.”

And, in one participant’s words: “They could be immortal.”

This wasn’t what we expected. We thought people would naturally imagine how some things could be better and other things could be worse. Instead, they imagined how everything could be better.

And it wasn’t just a few people. Literally 90% of participants imagined how things could be better, on average. In psychology, that pretty much never happens. Even with a question as obvious as “would you rather get five dollars or get hit in the head with a wrench,” you might get something like 90% of participants saying “five dollars please” but the rest of them would say “wrench” either because they’re trolling you or they have a wrench fetish. (Scott Alexander calls this the Lizardman Constant.)

So what’s going on? Here are three immediate thoughts we had.

#1: Are people just complaining?

Nope. When we asked people about how good these things are right now, people were perfectly happy to tell us that lots of things are great. In fact, only a few items got negative ratings on average, like news, politics, and the coronavirus.

#2: Is this one of many optimism biases?

We already know that people have a general bias towards optimism. But optimism is the belief that things not only could get better; they will. So did our participants think that things will get better?

Not really. We also asked participants how likely each of their imagined changes were, from 0 (definitely will not happen) to 100 (definitely will happen). The most common likelihood for positive changes was 0%, followed by 50%, followed by 80%. So people are imagining a mix of things that might happen and things that will definitely not happen, according to them. People are happy to speculate about their pets learning to talk, but they don’t think it will happen any time soon.

People did think that good things are slightly more likely to happen than bad things, so there is a dash of optimism bias in here. It just doesn’t explain the main finding.

#3: Did people assume that when you ask “how could things be different” you really mean “how could things be better”?

This would make a lot of sense. If you ask an interior designer how your home could be different, they won’t tell you, “Well you could have a bunch of stray dogs come in here and barf everywhere and then we could set your chaise lounge on fire, that would be different.” Instead they’d probably tell you something like, “We could paint it a nice shade of pearl." Maybe in most cases, people interpret requests for changes as requests for improvements.

There’s one piece of evidence against this possibility: 51% of participants gave us at least one way things could be worse. (For instance, one person said that pets “could have fleas.”) It would be pretty odd for participants to assume that obviously we wanted them to tell us how things could be better, and then they sometimes tell us how things could be worse.

But hey, it’s possible! So we ran another study.

STUDY 2: WAS IT SOMETHING WE SAID?

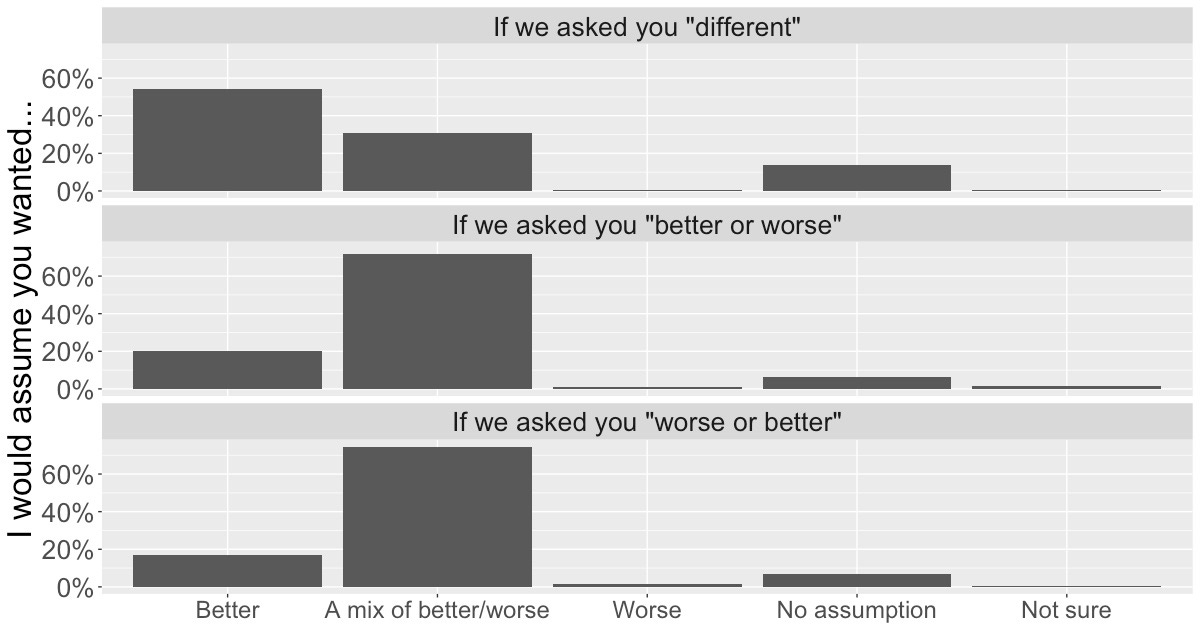

We got another group of 169 people and asked them, “If we asked you how [ITEM] could be [“different”/“better or worse”/“worse or better”], would you assume that we wanted you to list ways it could be better, ways it could be worse, a mix of better/worse, would you not assume any of the above, or are you not sure?”

Sure enough, a slight majority thought “different” meant better. Most people thought that asking for ways something could be “better or worse” or “worse or better” meant we wanted a mix of better and worse.

Great, we thought. If this is all about people thinking “different = better” if you ask them to imagine how things could be “better or worse” or “worse or better,” they should give you different answers.

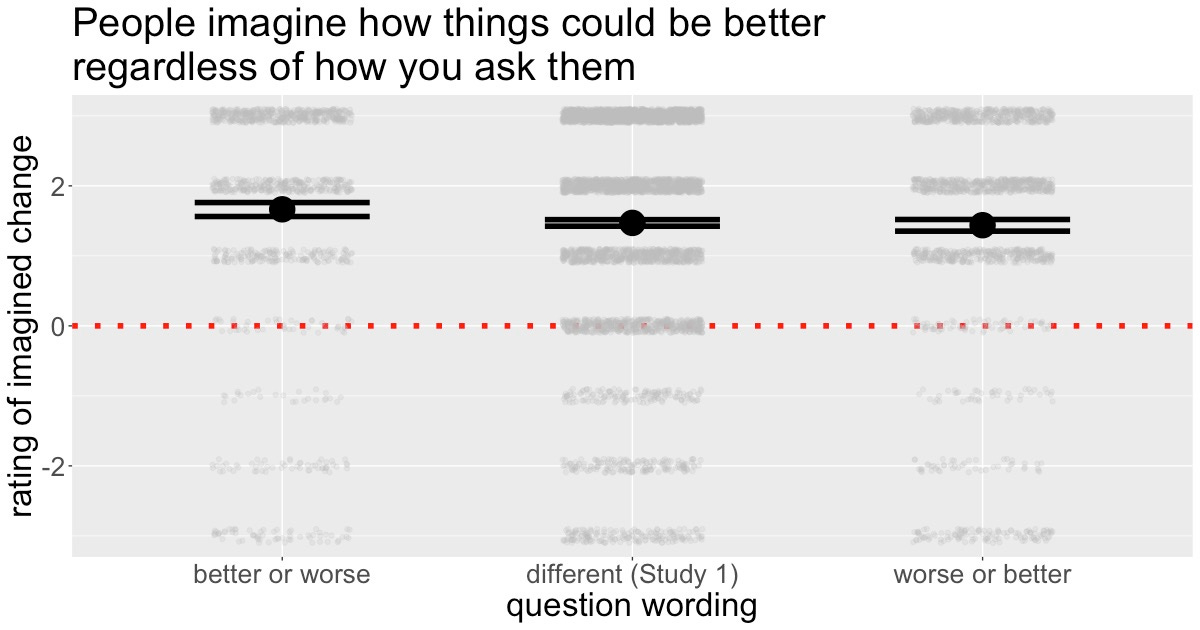

STUDY 3: BETTER AND WORSE MAKE NO DIFFERENCE

We got another 158 people and ran Study 1 again with slightly different wording. This time, we asked half of them “How could [ITEM] be better or worse?” and the other half, “How could [ITEM] be worse or better?”

It made no difference. Once again, people imagined ways that things could be better, on average. This again happened on every item, and in fact, the ratings were virtually identical across all three wordings. So this doesn’t seem to be about the wording of the question.

Okay, we thought. Do people only do this when we ask them weird questions like “How could your refrigerator be better or worse?” Or do people do this naturally in their everyday lives?

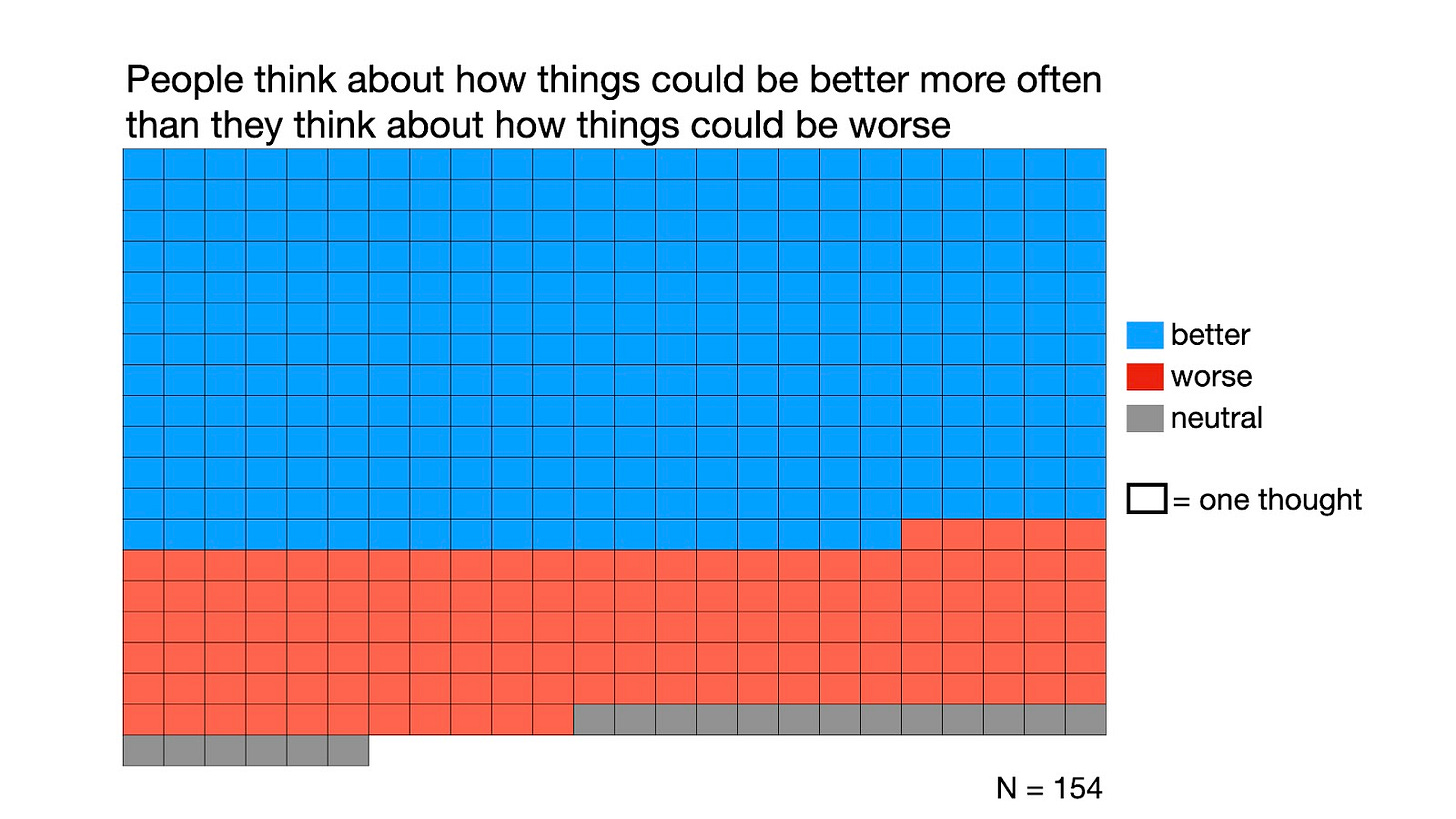

STUDY 4: HEY WHAT’RE YOU THINKING ABOUT

To find out, we got another sample of 154 people and simply asked them to list three thoughts they had recently, that were about how something could be better or worse. Then we asked them whether those thoughts were about how something could be better, worse, or neutrally different.

Two thirds of the thoughts people reported were about how something could be better.

At this point it seems like people have a pretty strong tendency to think about how things could be better. But which people?

We checked whether people’s tendency to imagine how things could be better had anything to do with their gender, race, education, or politics. It didn’t. Older people did this more than younger people in Study 1, but not in Studies 2 or 3. Of course, there’s a lot more to people than whether they are old and whether they have a high school diploma.

We thought being anxious, depressed, or neurotic might make a big difference. Maybe people who feel really bad can easily think of ways that things could be better (e.g., “I could feel less bad”). Or maybe they feel bad because they’re always thinking about ways that things could get worse (“What if I die alone?”). It would be cool to know either way, so we ran another study.

STUDY 5: INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

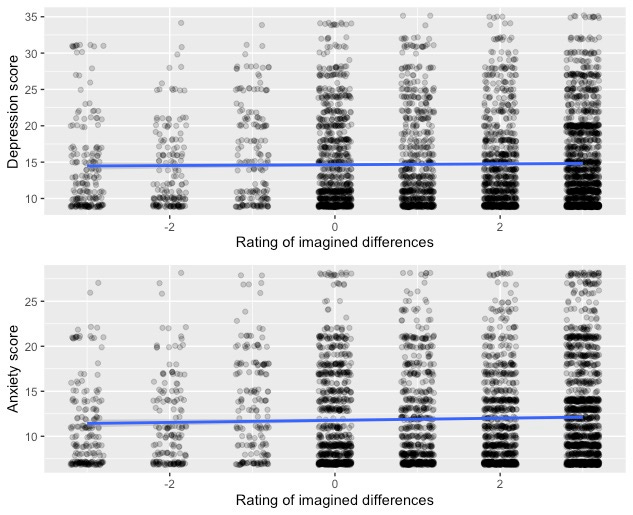

We re-ran Study 1 with another 250 people. This time, we also had them fill out a depression scale, an anxiety scale, and a Big 5 personality questionnaire, which includes a measure of neuroticism (sometimes this is called “emotional stability” because that sounds nicer).

Once again, people imagined how every single item could be better. (That’s replication, baby. 😎)

Depression and anxiety made no difference: people imagined how things could be better regardless of how depressed or anxious they were. Just look at how flat these trend lines are:

Neuroticism didn’t matter either (controlling for all other personality variables). But weirdly enough, people who were more open to experience were more likely to imagine how things could be better. We don’t have any explanation for this, and maybe it doesn’t mean anything. No other personality variables made any difference.

These results really surprised us. You’d think depressed, anxious, and neurotic people would be especially able to think of ways things could be better, or that they would always be worrying about ways things could get worse. But nope, they look just like everybody else.

Of course, so far we’ve only been looking in the good ol’ US of A. Famously, some people live in the United States, and other people do not. What if this effect is all about being an American? Maybe there’s something in our can-do culture that makes us always imagine how things could be better.

STUDY 6: POLISH FOLKS

So we got 95 Polish people, gave them the same list of items, and asked them how each thing could be different. This was a direct replication of Study 1, just with a different population.

“Why Polish people?” you might ask. To which we say: what, you got a problem with Poles? Not a fan of pierogi, paczki, and Dyngus Day?

Also, there just happened to be a sizable number of English-speaking Poles on the website we use to recruit participants, so we went with Poland. By one measure of cultural differences, the US is about as far from Poland as it is from India, Russia, South Korea, and Zambia, so this seemed like a good opportunity to test whether culture makes a difference.

It didn’t. Polish people also told us how things could be better. Again, this happened on every single item.

These Polish folks were answering in English, though, so it’s still possible that there’s something unique about the English language that leads people to imagine how things could be better. What if we asked people from a different culture in a different language?

STUDY 7: MANDARIN

We had the whole study translated into Mandarin Chinese. (Huge thanks to our research assistant Megan Wang for doing the translation, and Vanna Qing for proofreading the translated survey.) Then we recruited 307 Mandarin-speaking Chinese citizens who currently live in China. We adapted the items a bit for this sample—we replaced “Google” with “Baidu”, etc., but otherwise the design was a replication of Study 3. (We randomized people to imagine “different”, “better or worse”, or “worse or better”.)

The results were exactly the same. For every single item, participants imagined how things could be better, on average.

STUDY 8: THINK FAST

I have a confession to make: I don’t remember why we ran this study. I definitely remember seeing the results and going “yes!! We nailed it!! It all makes sense!” but now I can’t remember why. I asked Ethan about it and he was like, “bro I do not even remember RUNNING this one.” So if you can figure out why we ran this study, please let us know.

Anyway, here’s what we did. We got another 187 people and randomly assigned them to imagine how each item could be better, worse, or different. We told them they’d earn a $0.25 bonus if they listed more ways than the average participant did. (That’s a small amount of money in the scheme of things, but it seems bigger when you’re doing a short study for a dollar.)

People actually came up with fewer ways that things could be better, compared to worse or just different. People assigned to imagine “better” came up with 5 ways, on average, while people assigned to imagine “different” or “worse” came up with 5.5 ways.

So even though people have a huge bias toward thinking about how things could be better, it’s actually harder to do that than to imagine how things could be worse! Somehow they do it by default anyway.

A QUICK RECAP

When you ask people to imagine how things could be different, they imagine how things could be better. This doesn’t depend on how we word the question, and it happens in people’s everyday thoughts. Everybody seems to do it; demographics make little difference. Polish people also imagine how things could be better, as do Chinese people answering in Mandarin. And people imagine how things could be better even though it appears to be harder than imagining how things could be worse.

This tendency may be fundamental, because it seems awfully hard to make it go away. As I’ve written before, lots of published psychological findings may be a big stinkin’ load of hogwash. Some of that is because of statistical misunderstandings and some of that is because of outright fraud, but some of that is because most of what we discover in psychology is extremely contextual. Often, if you change the circumstances even a tiny bit, the effects change too.

So far, this finding doesn’t seem to be like that. We can’t find a single thing that people, on average, imagine being worse. Nor have we found any group of people that doesn’t seem to do it. In psychology, this pretty much never happens. So we’re excited.

WHAT ABOUT OUR ORIGINAL HYPOTHESIS?

It does look like we were wrong about the whole thing where people think Congress is bad because they can easily imagine how Congress could be better. People can easily imagine how everything could be better.

We did sometimes find that people were more likely to say that bad things could be better, compared to good things. But not always. We found the opposite in Study 4, when we asked people about their naturally occurring thoughts, and in Study 7, when we asked people in Mandarin. In those studies, the more that people thought something was already good, the more they thought about how it could be better. And in Study 8, when we asked people to come up with ways things could be better, they came up with just as many improvements for good things as for bad things. We’re not really sure why that happened.

Regardless, we think it’s safe to send our original hypothesis to that big farm upstate where it can run and play with other falsified hypotheses.

WHY DOES IMAGINATION WORK LIKE THIS?

Honestly, who knows. Brains are weird, man.

When all else fails, we can always turn to natural selection: maybe this bias helped our ancestors survive. Hungry, rain-soaked hunter-gatherers imagined food in their bellies and roofs over their heads and invented agriculture and architecture. Once warm and full, they out-reproduced their brethren who were busy imagining how much hungrier and wetter they could be.

But really, this is a mystery. We may have uncovered something fundamental about how human imagination works, but it might be a long time before we understand it.

PERHAPS THIS IS WHY YOU CAN NEVER BE HAPPY

Everybody knows about the hedonic treadmill: once you’re moderately happy, it’s hard to get happier. But nobody has ever really explained why this happens. People say things like, “oh, you get used to good things,” but that’s just a description, not an explanation. Why do people get used to good things?

Now we might have an answer: people get used to good things because they’re always imagining how things could be better. So even if things get better, you might not feel better. When you live in a cramped apartment, you dream of getting a house. When you get a house, you dream of a second house. Or you dream of lower property taxes. Or a hot tub. Or two hot tubs. And so on, forever.

A FINAL NOTE ABOUT DOING SCIENCE

The paper you just read could never be published in a scientific journal. The studies themselves are just as good as the ones Ethan and I have published in fancy journals, but writing about science this way is verboten.

For instance, in a journal you’re not allowed to say things like “we don’t know why this happens.” You’re not allowed to admit that you forgot why you ran a study. And you’re DEFINITELY not allowed to talk about Dyngus Day. You’re supposed to be very serious; a reviewer once literally told me that my paper was “too fun” and that I should make it more boring. You’re supposed to pack your paper with pointless citations because reviewers might like your paper more if they see their name in it. And if reviewers don’t like your paper, they’ll reject it and nobody will ever see it.

This is a stupid way to do science. It goes against every single one of the scientific virtues. It leads to publication bias—reviewers prefer studies with “statistically significant” results that confirm their preexisting biases, filling “the literature” with junk articles that are often never cited at all. Doing peer review this way also costs more than a billion dollars a year, money that could instead be spent on more elaborate Dyngus Day costumes.

Instead, you can review this paper right here in the comments, or on your own blog, or on Twitter, if it still exists by the time you read this. And if you can find us on the street, you can shout your review directly at us, and we’ll shout back. Remember that you can find everything you need to replicate all of our studies and analyses here.

If we did publish this in a journal, there’s a good chance you wouldn’t be able to read it at all unless a) you belong to an institution that pays millions of dollars in scientific journal subscriptions, or b) you use a pirate website like Sci-Hub, which we of course do not recommend because it’s illegal and bad.

It’s almost as if we can’t help but imagine ways that scientific publishing could be better. Somebody should write a paper about that.

Thanks to Daniel Gilbert, Fiery Cushman, Tali Sharot, Yev, hugo villeneuve, Sean Trott, Marco Plebani, Bash, Bimal Shah, Samvit Jain, Amy Summerville, Arbituram, and Lukas Neugebauer for their comments and reviews.

Fascinating research and as a fellow academic, hell yeah to everything you had to say about scholarly publishing! Learning to write academic papers in grad school (i.e. how to make anything of the slightest interest boring and incomprehensible) almost destroyed me. Thanks for showing how fun science can be.

I’ve always thought that scientific papers needed more things like “That’s replication, baby.😎”

Adam, I really appreciate this. I’m sure it takes some amount of courage as an academic to break the mold like this. Do you think it’s realistic that science could actually be reformed in this direction?… Is it as simple as more people just deciding to write their papers like this? And, what about the downsides? Call me an optimist, but I’m sure there are some good reasons scientific papers are written the way they are. Maybe one is that the more expertise/knowledge you assume of the reader, the easier you can communicate extremely narrow and nuanced ideas that make up the majority of publications, the inch-at-a-time progress in science. That’s not to say that scientists always do this well or scientific writing hasn’t moved beyond this to a different thing. But do you think we will always need hard to read scientific papers?