You'll forget most of what you learn. What should you do about that?

Are we crazy, or are we missing a big secret?

The more I think about this, the weirder it seems.

Almost all of us start going to school when we’re three or four, and we don’t stop until we’re somewhere between 18 and 22. Some of us, having nothing better to do, keep going to school long into our twenties and beyond.

And yet, invariably, most of what we learn vanishes. We keep a few things: multiplication, spelling, “Columbus sailed the ocean blue in fourteen-hundred and ninety-two.” But if we had to retake the exams, we’d flunk.

Just how fast do we lose our learning? You could do the responsible thing and consult Table 1 of this review paper and find that a) studies rarely follow up more than a year later to see what people remember, b) for the studies that do look at longer spans of time, people can lose anywhere between 14% and 85% of their knowledge in just a few years, and c) it depends on all kinds of factors, like the subject, how people are tested, and whether they ever used the material between learning and recall.

Or, you could just watch this episode of Are You Smarter Than a 5th Grader? where a grown woman stands in the midst of horrified 10-year-olds and shouts, “THERE’S THREE-HUNDRED AND FIFTY-TWO FEET IN A YARD!”

(As a little test of my own learning loss, I tried to remember every class I took in college. I stalled out at 19 out of 32 classes. It’s only been eight years and I’m already missing the headlines of 40% of my undergraduate education.)

This isn’t even just about mandatory schooling or higher education. You could, entirely of your own volition, take a class on CPR because you want to be able to save a life in an emergency. You could pay close attention to your instructor, do your practice CPR on the CPR dummy, and earn a CPR certificate. And, just a few years later, you could find yourself in a situation where someone needs CPR and suddenly realize you’ve forgotten how to do it. Is it 30 compressions for every 2 breaths? Or is it 15 compressions? Wait, are you actually supposed to do breaths at all? Oh, god!

So what are we doing here? Are we crazy? How should we feel about spending our lives learning and forgetting?

Here are a few perspectives I’ve heard that are meant to make this all make sense.

Learning is lossy and there’s no way around that. You have to encode 100 units of information if you want to retain even a few. This is simply a law of nature, and if you’re mad about it, wait until you hear about perpetual motion machines.

We definitely can’t expect to remember everything. But it’s not like I remember 20% of every class I took, or even 5%. Entire chunks of my education are now just black holes. For instance, I know I learned something about ancient Sumeria at some point, but all I have now is the name “Sumeria” floating around in my head. Actually, spellcheck is informing me that “Sumeria” might not even be a word. Ah, ok, a quick Google search reveals I was thinking of “Sumer.” Well then. Glad we spent two months on it in ninth grade social studies.

In fact, it’s possible that trying to learn lots of things in the hopes of remembering a few of them is exactly the wrong strategy. Memories can compete with one another; remembering ancient Sumer can make it harder to remember other ancient cities like Çatalhöyük (another name floating uselessly in my head). We don’t know what the right amount of information is, but drowning your brain is probably the wrong strategy.

The important stuff sticks. People remember multiplication because they keep using it. The fact that we lose so much means that we’re learning a bunch of useless stuff that our brains dutifully erase

I’m sure plenty of the stuff I learned wasn’t useful and I’m glad my brain dumped it. But it also dumped tons of stuff I would have preferred to keep. For example, much of the stuff I’ve learned about psychology over the years would have come in handy later, and whenever I rediscover some finding I’ve forgotten, I curse my brain for forgetting it. So while we’re more likely to lose low-priority information, even high-priority stuff disappears.

It doesn’t matter how much students remember because what we’re really doing is teaching them how to learn.

You’ll often hear this from presidents of liberal arts colleges, as if you only start “learning how to learn” when you turn 18 and start paying $60,000 a year for the privilege. Shouldn’t learning how to learn be the first thing we do? What were we spending all of our time on?

We do, in fact, know quite a bit about how people learn, and almost nobody learns it. When you want to remember something you’ve read, do you highlight it, reread it, or summarize it afterward? Those strategies don’t work very well. Do you cram for tests? Also bad. Plus, the “final” in “final exams” gives students license to purge their knowledge once the semester is over. Anybody who has “learned how to learn” shouldn’t do these things, but visit a university library at 2 AM during exam week and see how well that’s working out.

All of these explanations may have a little nugget of truth in them, but none of them makes me feel better about how much I’ve learned and later forgotten. I think they all miss something big because they assume that learning is about acquiring knowledge or skills. That sounds reasonable, but it’s wrong.

I’m here to tell you that learning is all about vibes.

HOW YOU MAKE THEM FEEL

There’s an excellent quote that goes something like this:

I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

(Fittingly, this quote has been misattributed to a half-dozen people.)

There’s something deeply true here, and it applies to more than just how people remember each other. I think it applies to how people remember everything.

Here are things I don’t remember from high school:

The phone number of my best friend, despite dialing it hundreds of times.

How to play a high D on the trumpet, despite playing it for years.

Almost everything I memorized for quizbowl competitions, despite carrying around freezer bags full of flash cards and testing myself on them over and over for months at a time. For instance:

Here are things I do remember from high school:

How fun it was to call my best friend and talk for hours.

How exciting it was to march onto the football field, trumpet in hand, and play a halftime show.

How much I despised my school’s rival quizbowl team, how infuriating it was when their coach called us “reasonably intelligent,” and how I was so nervous before our championship match against them that I nearly threw up.

It’s especially remarkable that my brain ditched all the facts and kept all the feelings, because there were big incentives to keep the facts and none to keep the feelings. The feelings never showed up on an exam, nor did they score me points in a quizbowl match. I never took notes on them, I haven’t spent much time reminiscing about them, and I never really told them to anyone––even if I tried, it’s hard to capture a feeling in a few words, and I’m merely gesturing toward them here. And yet, despite explicitly directing my brain to store the facts, it stored the feelings instead.

Maybe I’m just a big sentimental softie, but I bet if you peer deep into your past, you don’t see a list of names, dates, and places. Instead, I bet you get a hodgepodge of images and events, and I bet that some of the details are hazy or mixed up, like who was there, what they were wearing, or whether it happened when you were six or when you were eight. But I bet the feelings are clear. You’re probably not confused about whether you felt proud or afraid, welcomed or rejected. And I bet that although you could describe these memories to me—a golden-hued day at the zoo, the last fight your parents had before they got divorced—the words would leave a lot out. To really get me to understand, you’d need to hook your brain up to mine, Avatar-style, so I could feel what you felt.

So far, I’ve used the word “feelings” to describe these indelible, ineffable memories. That implies that these memories are all about emotions, and no doubt emotions are part of them. But there’s even more than that. It’s hard to describe, but: the transition of winter into spring, seeing the Statue of Liberty in person for the first time, the phase shift that happens when you enter a dance party, the last day of camp, being at a wedding that probably shouldn’t happen—I’m sure these all evoke images and emotions, but there’s something underneath it all, binding it all together. That’s what I mean by a feeling. A combination of emotions, aesthetics, meaning, and values. And when you layer feelings on top of each other, you get a vibe. (It’s a silly word, but it’s the only one that fits.)

Normally this is where I’d bring in a bunch of psychological research, but the literature is silent on all this. Vibes don’t fit well anywhere on the memory org chart, having one foot in episodic memory and one foot in implicit memory. It’s hard to study memories of qualia, the experience of experiencing, because we don’t really know what that is and it doesn't play well with classic methods of memory research like forcing people to memorize word-stem pairs.

If we’re on the right track here, the picture looks something like this:

Knowledge fades fast, especially when you don’t use it. In the words of the late, great psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, “All sorts of ideas, if left to themselves, are gradually forgotten”

Feelings, or vibes, on the other hand, seem to stick around a lot longer.

If true, this seems pretty important to anybody who hopes to teach or learn anything. Almost all of education centers around knowledge and skills rather than vibes. The SAT assesses whether you remember what an adverb is or how to use the quadratic formula. When a colleague wants to teach a class that you’ve taught, they’ll ask for your slides, not your vibes. In Ohio, where I went to primary and secondary school, students are supposed to learn exciting facts like, “Key events and significant figures in American history influenced the course and outcome of the American Revolution”; there’s nothing in the standards about what this is supposed to feel like. But once the semester is over, those “key facts and significant figures” will begin leaking out of students’ brains. The vibes, however, will still be there.

FORGET FACTS; VIE FOR VIBES

It may be disappointing that the human brain loses knowledge so fast, but it’s a miracle that it keeps vibes so long. Vibes may sound flimsy, ethereal, and useless, but in fact they’re far more powerful than a pile of facts or a couple of skills.

Here’s an example. At some point, everybody must solve a math problem called “how much should I save for retirement?” This involves calculating compound interest, which looks like this:

If you can produce that from memory, your math teacher would count it a huge victory. But of course you didn’t actually need to remember it; you can just Google it. What you really needed was a) to recognize that this is a solvable math problem, b) to feel like you can solve it, and c) to have some sense of where to begin. These are vibes.

But figuring out how much to save for retirement is actually way more complicated than applying a formula. Most investments involve some amount of risk, which means you can’t be sure about how much you’ll earn. That means you should model a few different scenarios, which means you have to figure out which scenarios are reasonable. If you remember your economics, you may have a head start here. But nobody can tell you what’s going to happen, or how much risk you should take. This, too, is beyond the realm of knowledge and into the realm of vibes.

And to figure out how much you need to save, first you have to figure out how much you need. What’s your definition of the good life, and how much money does it require? If you’re lucky, you may remember from your philosophy class what Plato or Hume said about the subject. But defining your own good life is about as deep into the vibes as it gets.

So what might look like a simple plug-and-chug situation is, in fact, a whole tangle of problems to solve. Untangling them requires some knowledge, yes, but knowledge is cheap and easily acquired. What you really need is curiosity, self-efficacy, perseverance, perspective, and hope. And those are vibes.

GOOD VIBES & BAD VIBES

I hope I’ve convinced you that vibes are important, perhaps more important than anything that can be put on a PowerPoint slide or tested on a final exam. But it’s really hard to distill a vibe in just a few words––that’s the whole point!––so let me give you a better sense of what vibes are all about by describing two classes, one with very bad vibes and one with very good vibes.

When I took a cognitive psychology class in undergrad, the professor began the first lecture by saying—literally!—“Cognitive psychology is pretty boring.” I remember almost nothing else from the class, but I certainly remember that.

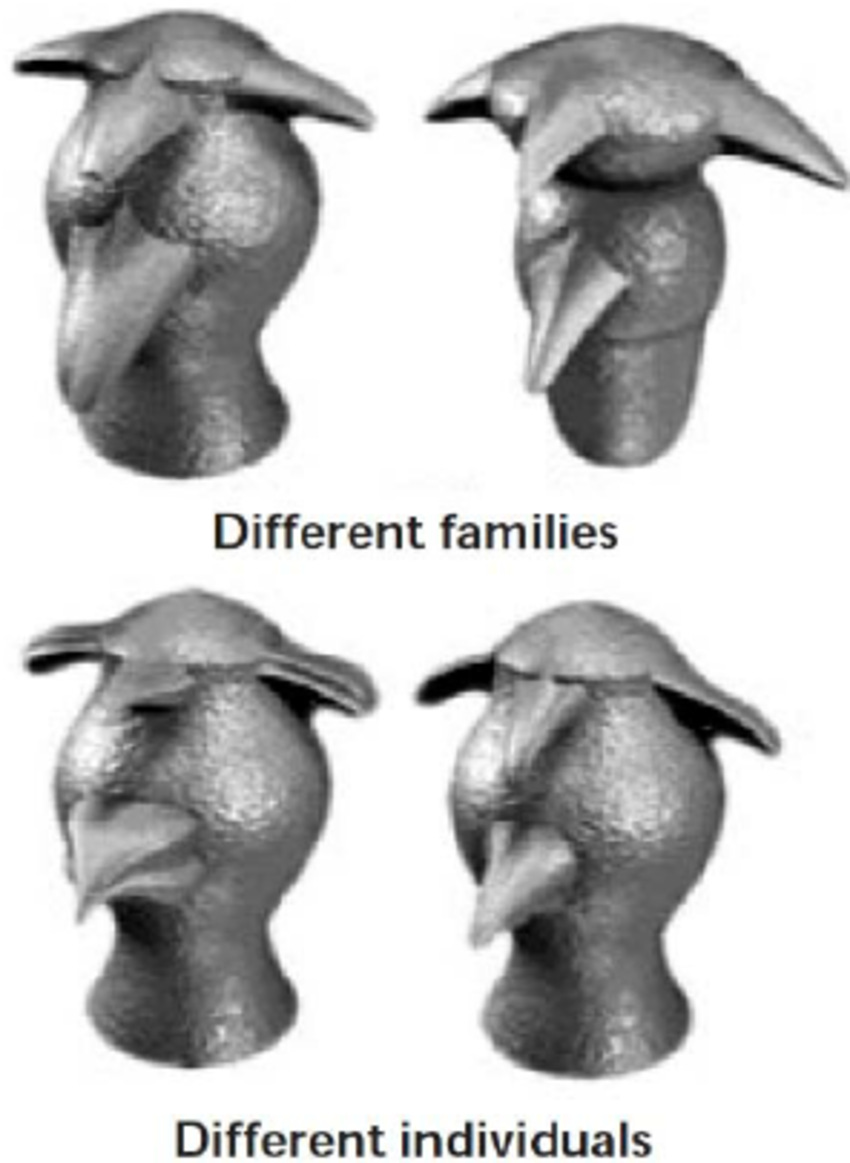

Actually, I remember exactly one other thing. I remember GREEBLES:

Why do I remember these? Because they’re fun. I was surprised that, in the midst of such a supposedly boring field, someone was like, “For our studies, let’s make a bunch of bird-creatures and call them Greebles.” I even remember what the Greebles were for, which was settling a dispute about the Fusiform Face Area—is it truly a patch of brain dedicated to processing faces, or it is really about expertly processing fine details and configurations? The Greebles people showed that as people get acquainted with Greebles, their FFAs start lighting up in response to Greebles just like they do in response to human faces. Skeptics pointed out that Greebles actually kind of look like faces, so the controversy raged on. But at least we were having a good time!

(My professor was wrong, by the way. Cognitive psychology is fascinating!)

So my cognitive psychology class had awful vibes except for these weird little bird people. In contrast, I took a Psych 101 class where the vibes rocked. The professor had this whole opening bit, which I can only convey with like 10% of the vibes:

“I love M&Ms,” he said, holding a bag of them up to the light. He talked about the miracle of perceiving objects against backgrounds. He tossed the bag to a student in the audience, who caught it, and the professor explained all of the calculus that student had to do in order to calculate the trajectory of the M&Ms and all of the motor commands his brain had to issue to catch it.

“Now, toss it back,” he instructed. The student obliged.

“Obedience, we’ll talk about that too,” the professor continued. Everyone laughed. He gave the M&Ms back to the student. “I’m just kidding, thank you, those are for you. Okay wait, toss it back one more time?”

The student held on defiantly.

“Ah, learning! We’ll cover that in week six.”

From that moment onward, the professor talked a million miles a minute, leading us on a semester-long tour through the wonders of psychology. He never seemed to take a breath. On the final day, as he finished his last sentence, he let a silence linger for a second. And I started weeping. I was overwhelmed by the beauty of what I had just learned. I couldn’t believe something so exciting existed, and I could be a part of it. I wanted to be a psychologist more than anything else in the world. The whole class stood and clapped for a long time.

Now that is a vibe.

TAKING VIBES SERIOUSLY

When I took these classes. I spent several months attending lectures, doing readings, completing homework assignments, and taking exams. I poured a lot of effort into all of them––psychology was my major, and now it’s my profession. And yet, less than ten years later, all I really remember from those classes is how they made me feel about psychology.

Is that all we can hope for? I think yes, it is.

Is that a huge bummer? I think no, it isn’t.

Let me give you one last example of the power of vibes, this time from the point of view of the teacher rather than the student. The thing about receiving vibes is that you often don’t appreciate or can’t even articulate what you’re picking up—you just don’t have the necessary expertise, perspective, or vocabulary yet. Even though all I remember from Psych 101 is how it taught me to love psychology, I think I was actually changing in ways that I didn’t even realize, but my professor probably did.

So here’s what it looks like from the other side. In addition to learning all of my squishy psychology, I’ve also had to learn statistics and programming. And I have, on several occasions, attempted to teach my students and research assistants the R programming language, which is a widely used data analysis tool. You might think, as I once did, that learning R should be all about knowledge and skills. After all, it’s a whole world defined entirely by functions and how you put them together. So just learn the names of the functions, practice using them, and you’ll learn R.

But in reality, learning R doesn’t go anything like that. Instead, it goes like this:

Student: How do you run a t-test?

Me: You use t.test()

Student: Yeah that didn’t work.

Me: What did the error message say?

Student: It’s like “object ‘rating’ not found.” But I know the data is there.

Me: Oh, “rating” is a column within your data frame. But R doesn’t know that. So you need to either put “data$rating” in, or use…what’s your data called?

Student: “data"

Me: So you can use “data = data.”

I know these words sound stupid even as they’re coming out of my mouth. And the student does too. It’s like I’m a wizard trying to explain some arcane ritual. “Your potion didn’t come out because you sliced the eye of newt too thin. As the Dark Lord Graalnak wrote in the third volume of the Perfidium, ‘slice too thin, we may not begin.’ Oh, you want to know how thin should you slice? I don’t know, look it up on PotionOverflow.”

The students who ultimately succeed in learning R are not the ones who force themselves to memorize functions or do a bunch of coding drills. They’re the ones who accept they will feel stupid and that most of the rules will at first seem totally arbitrary, and who understand that they will gain great power if they just keep going. Students often don’t like this vibe because it feels infantilizing. For most of them, the last time they learned a seemingly arbitrary language, they at least got to poop in their pants while doing it. Now, in exchange for very politely not pooping in their pants, they expect things to make a little sense. And I have to explain that, unfortunately, they gave up that right for nothing.

I’ve found that the best way to transmit this vibe is to show them just how dumb I am.

Student: How do I change the size of the axis labels on a plot?

Me: Oh, I always forget how to do that. Just Google it.

Student: It says “non-numeric argument to binary operator.”

Me: Uh. *types something* Nope. Um. *types something* Yeah that’s not it. Uh. *types something* Hmm. Try Googling it.

Student: What does it mean when it says “json—”

Me: GOOGLE

Through it all, I purposefully remain upbeat, unflappable, and unashamed. “This is normal,” I say. “You guys are doing great! Nobody is crying.” They look at me skeptically. “I cried lots of times,” I explain. This they can believe; I’ve got the looks of a guy who’s prone to blubbering in psychology classes.

It takes a while, but if the student is willing and I have them in class or the lab for long enough, they eventually get it. The crazy thing is: they might not even know they got it. They may simply leave with a vague sense that R is cool. But woven into that feeling are vibes like “I can get better at this” and “it’s okay to feel dumb while doing this” and “if I learn R, I can do all kinds of useful things.” That’s all they need. They can Google the rest of the stuff, just like I do.

ONE LAST NOTE, THIS ONE ABOUT COLLEGE

Some economists think there are really only two reasons to go to college. First, you signal to employers that you’re smart and hardworking. And second, you make friends who start companies or whose parents are CEOs or federal judges, and they give you opportunities. To an economist, going to class is just a ritual, or simply something to pass the time between parties. And if you measure the value of an education by how well people would perform on their final exams five years later, that makes sense.

But if you care about vibes, going to class looks very different, as does everything else about education. Class is a place where you can pick up vibes like “learning is important” and “even amateurs can contribute useful knowledge” and “people who make good points and aren’t assholes about it are respected.” Enthusiastic professors can give you the vibe of “there’s so much we don’t know, and it’s fun to figure it out.” Your classmates can give you vibes like, “you learn a lot more when you’re not surrounded by the same kind of person all the time.” Even the buildings can emanate a vibe of “teaching and learning are ancient, sacred traditions.”

None of this will happen, though, without proper vibe management. It is possible for teachers to send a vibe of “success in school depends on satisfying my whims.” Peers can give you the vibe of “this is all just a game before we go do whatever will pay us the most.” Buildings can say “it’s cool to cause the opioid crisis as long as you donate some money afterward.” Nobody ever has to state any of this explicitly, and usually nobody does. Vibes are like dark energy: invisible, but evident everywhere.

So yes, if your heart stops and you need CPR, you would really like it to be performed by someone who remembers the steps. But they don’t have to nail it—imperfect CPR is better than none at all. What you really want is not someone who can ace a bunch of multiple-choice questions about CPR, but someone who has the desire to save your life, the confidence to jump in and start compressions, and the wherewithal to keep it together until the paramedics arrive. These things can’t be written down and turned into a checklist. They are vibes, and you better hope the person squeezing your heart got some good ones.

Your point here makes a lot of sense to me. But going back to elementary school for a minute, I think there's another possibility. When you learned about Sumer but also Columbus and also the American Revolution, you were picking up a lot of background information that you take for granted now. Do you know (now) that the Sumerians didn't have telephones? Do you know that big sailing vessels were important in history? Do you know that machine guns came around sometime between, say, the American Revolution and World War II? Do you know that people of the past spoke a bunch of different languages, and some of them had writing but some didn't? That and an unfathomable amount of other background stuff is what you really learned by studying specific topics in elementary school. That's what I think, anyway.

I find my brain has a"Raiders of the Lost Ark" type warehouse stacked with crates. Ask me from a cold start to write everything I know about (Sumer)(fill in any topic) and it won't fill a sticky note. But let the situation warm up, put me at a table with 2 or 3 other folks all working/discussing at remembering tidbits about (Sumer), and my brain will...churn. Memories will be word-associated, triggering crates to be prybarred open in that metaphorical warehouse, dust billowing. Facts about (Sumer) expressed at the table will be increasingly met with "Oh, yeah, that sounds familiar", "Oh, that's right!", all the way to actual offering of my own tidbits of information.

Playing any game of "Trivial Pursuit" or keenly following an episode of "Jeopardy" will start that churning resurrection of knowledge/memories.

A clearcut example in my life was a few years ago. I sat down to draw a map of the little town where I spent ages 4-7. Casting my mind back thru the decades, the map began mostly blank and what was there was pretty dry. Then the churn began. Here was the barbershop, here was the drygoods store, here was the school, here was the gas station...and it kept going. I didn't just remember the gas station, but the name of the owner...and she had an iron Case eagle logo-statue...and before I finally called it quits, I had a richly detailed map of landmarks, places, and names.

I guess it's all there. Just requires a sincere need to haul it out in the open.