Bamboozle me, daddy

OR: The triple-decker fallacy

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky were two of the greatest psychologists of all time. Maybe the greatest. The fields we now call “behavioral economics” and “judgement and decision-making” are basically just people doing knockoff Kahneman and Tversky studies from the 70s and 80s.

(You know how The Monkees were created by studio executives to be professional Beatles impersonators, and then they actually put out a few good albums, but they never reached the depth or the importance of the band they were—pun intended—aping? Think of Kahneman and Tversky as the Beatles and the past 50 years of judgement and decision-making research as The Monkees.1)

Amos ‘n’ Danny were masters of the bamboozle: trick questions where the intuitive answer is also the wrong answer. Quick: are there more words that start with R, or words that have R in the third position? Most people think it’s the former because it’s easier to come up with r-words (rain, ring, rodent) than it is to come up with _ _ -r words (uh...farm...fart...?). But there are, in fact, more words where r comes third. That single silly example actually gives us an insight into how the mind calculates frequencies—apparently, not by conducting a census of your memories, but by judging how easy or hard it feels when you try to think of examples.

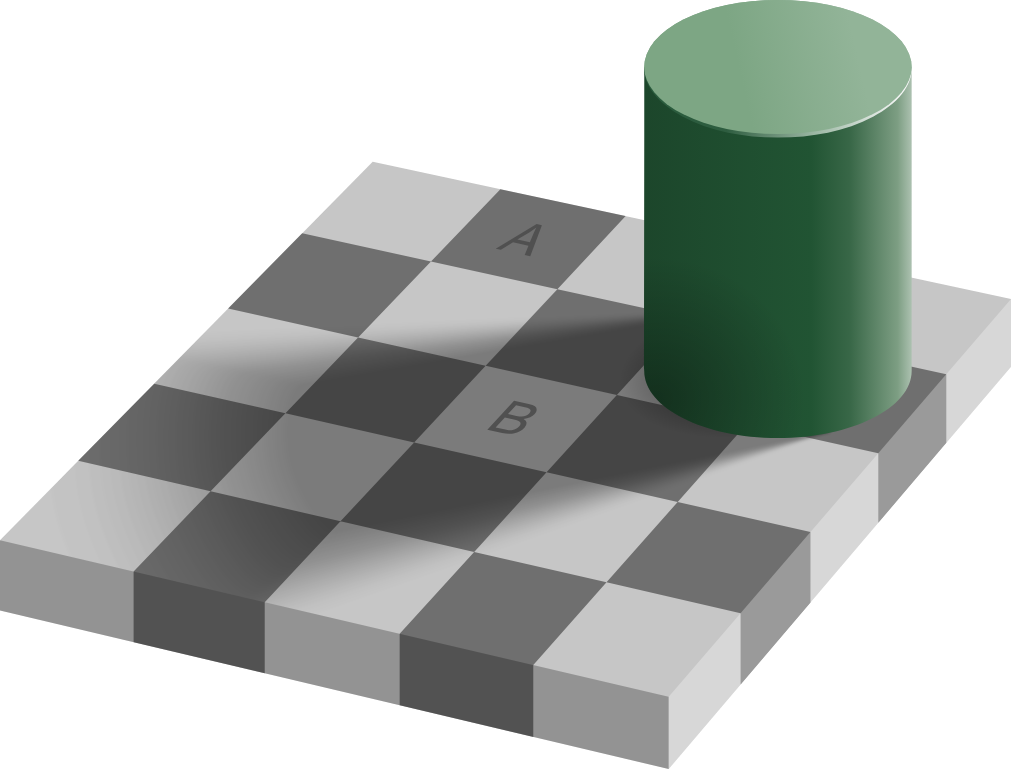

These little cognitive gotchas show us how the mind works by showing us how it breaks. It’s like a visual illusion, but for your whole brain. This is the understated genius of Kahneman and Tversky—it’s not like other research, where some egghead writes a paper about some molecule and then ten years later you can buy a pill with the molecule in it and it cures your disease. No, for K&T, the paper is also the pill.

But the duo was so successful that they have, in part, undone their own legacy. The tricks were so good that everybody learned how they worked, and now it’s hard to be bamboozled anymore. We’re no longer surprised when the rabbit comes out of the hat. And that’s a shame, because the best part of their work was that half-second of disbelief where you go “no no that can’t be right!” and then you realize it is right. That kind of feeling loosens your assumptions and dissolves your certainty, and that’s exactly what most of us need: an antidote to our omnipresent overconfidence.

I’m here to bring the magic back. I’m no Kahneman nor Tversky, but I can at least do two things: resurface some of their long-forgotten deep cuts, and document a few tricks that bamboozled the Bamboozlers-in-Chief themselves—including one that, I think, I have just discovered and am documenting for the first time.

Let’s see if we can find another rabbit in this hat.