How to feel bad and be wrong

OR: Rickets, please!

The human mind is like a kid who got a magic kit for Christmas: it only knows like four tricks. What looks like an infinite list of biases and heuristics is in fact just the same few sleights of hand done over and over again. Uncovering those tricks has been psychology’s greatest achievement, a discovery so valuable that it’s won the Nobel Prize twice (1, 2), and in economics, no less, since there is no Nobel Prize for psychology.1

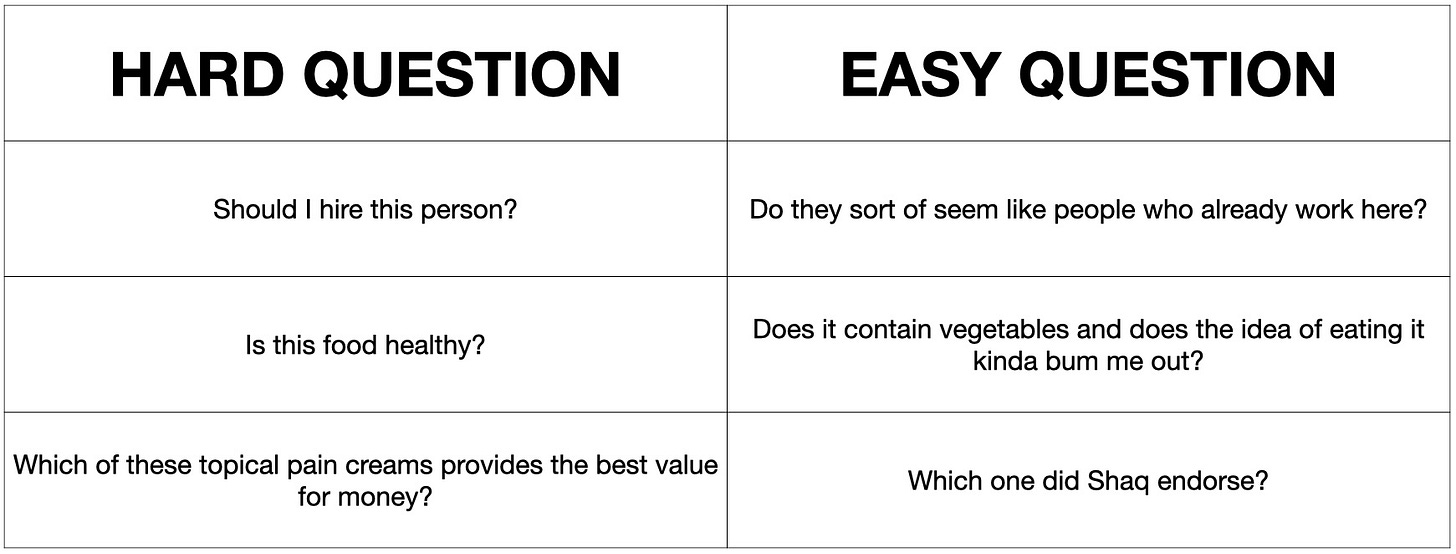

And yet, the best trick in the whole kit is one that most people have never heard of. It goes like this: “when you encounter a hard question, ignore it and answer an easier question instead.” Like this—

Psychologists call this “attribute substitution,” and if you haven’t encountered it before, that clunker of a name is probably why. But you’ve almost certainly met its avatars. Anchoring, the availability heuristic, social proof, status quo bias, and the representativeness heuristic are all incarnations of attribute substitution, just with better branding.

The cool thing about attribute substitution is that it makes all of human decision making possible. If someone asks you whether you would like an all-expenses-paid two-week trip to Bali, you can spend a millisecond imagining yourself sipping a mai tai on a jet ski, and go “Yes please.” Without attribute substitution, you’d have to spend two weeks picturing every moment of the trip in real time (“Hold on, I’ve only made it to the continental breakfast”). That’s why humans are the only animals who get to ride jet skis, with a few notable exceptions.

The uncool thing about attribute substitution is that it’s the main source of human folly and misery. The mind doesn’t warn you that it’s replacing a hard question with an easy one by, say, ringing a little bell; if it did, you’d hear nothing but ding-a-ling from the moment you wake up to the moment you fall back asleep. Instead, the swapping happens subconsciously, and when it goes wrong—which it often does—it leaves no trace and no explanation. It’s like magically pulling a rabbit out of a hat, except 10% of the time, the rabbit is a tarantula instead.

I think a lot of us are walking around with undiagnosed cases of attribute substitution gone awry. We routinely outsource important questions to the brain’s intern, who spends like three seconds Googling, types a few words into ChatGPT (the free version) and then is like, “Here’s that report you wanted.” Like this—

HARD QUESTION: AM I WORKING HARD ENOUGH? EASY QUESTION: AM I SUFFERING?

Lots of jobs have no clear stopping point. Doctors could always be reading more research, salespeople could always be making more cold calls, and memecoin speculators could always be pumping and dumping more DOGE, BONK, and FLOKI.2 When your work day isn’t bookended by the hours of 9 and 5, how do you know you’re doing enough?

Simple: you just work ‘til it hurts. If you click things and type things and have meetings about things until you’re nothing but a sludge pile in a desk chair, nobody can say you should be working harder. Bosses love to use this heuristic, too—if your underlings beat you to the office every morning and outlast you in the office every evening, then you must be getting good work out of them, right?

But of course, that level of output doesn’t feel satisfying. It can’t. That’s the whole point—if you feel good, then obviously you had a little more gas left to burn, and you can’t be sure you pushed yourself hard enough.

Perhaps there are some realized souls out there who make their to-do lists for the day, cross off each item in turn, and then pour themselves a drink and spend their evenings relaxing and contemplating how well-adjusted they are. I’ve never met them. Instead, everybody I know—myself included—reaches midnight with three-fourths of their to-dos still undone, flogging themselves because they didn’t eat enough frogs. None of us realize that we’ve chosen to measure our productivity in a way that guarantees we’ll fall short.

I think a lot of us, when pressed, justify our self-flagellation as motivational, rather than pathological. If you let yourself believe that you’ve succeeded, you might be tempted to do something shameful, like stop working. But as the essayist Tim Kreider puts it:

Idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice; it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets.

Which is to say, every day I wake up and go, “Rickets, please!”

HARD QUESTION: AM I GOOD? EASY QUESTION: AM I BETTER THAN OTHERS?

Speaking of games you can never win—

Sometimes my friend Ramon3 gets stressed about how much he’s achieved in his life, so to make sure he’s “on track,” he looks up the resumés of his former college classmates and compares his record with theirs.

Ramon has accomplishments coming out the wazoo, but he always discovers he’s not on track. You know how some colleges will let you take the SAT multiple times and submit all your scores, and then they’ll take your best individual Reading and Math tests and combine them into one super-score? Ramon does the same thing for his high-achieving friends: he combines the greatest accomplishment from each of his old rivals into a sort of Frankenstein of nemeses, a mythical Success Monster who has written a bestselling book and started a multi-million dollar company and married a supermodel and just finished a term as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

I think Ramon’s strategy is pretty common. It’s hard to tell whether you’re doing the right things. It’s a lot easier to look around and go, “Am I on top?” On top of what? “Everything.”

HARD QUESTION: HOW IS THE ECONOMY DOING? EASY QUESTION: IS MY SIDE IN CHARGE?

If you ask me to judge the state of the economy, I’ll give you an answer so quick and so confident that you can only assume I keep close track of indicators like “advance wholesale inventories” and “selected services revenue.” What I’m really doing is flashing through a couple stylized facts in my head, like “my cousin got laid off last month, seems bad” and “gas was $4.10 last time I filled up, that’s expensive,” and “the pile of oranges at the grocery store seemed a little smaller and less ripe than usual—supply chain??”

In fact, I don’t even need three data points. I can judge the state of the economy with a single fact: if my guy’s in the Oval Office, I feel decent. If my enemy is in there, I feel despondent. This is apparently what everybody else is doing, because you can watch these feelings flip in real time:

Two things jump out at me here. First, sentiment swings after the election, rather than the inauguration, meaning people are responding to a shift in vibes rather than policy. Second, those swings are 50-75% as large as the drop that happened at the beginning of the pandemic. When the opposing side wins the presidency, it feels almost as bad as it does when every business closes down, the government orders people to stay at home, and a thousand people die every day.

Here is actual GDP for that same span of time:

Pretty steady growth, except for one pandemic-sized divot that lasted a whole six months—and half of that time was recovery, rather than recession. GDP isn’t a tell-all measure of the economy, of course, but it’s a lot better than checking whether the president is wearing a blue tie or a red tie.

HARD QUESTION: IS THIS THING GOOD? EASY QUESTION: DO OTHER PEOPLE SAY IT’S GOOD?

I was once in one of those let’s-all-go-around-the-table situations where everybody says their name and something about themselves, and in this version, for whatever reason, our avuncular facilitator wanted us all to reveal where we went to college. After each person announced their alma mater, the man would nod reverently and go “Oh, good school, good school,” as if he had been to all of them, like he had spent his whole life as a permanent undergraduate doing back-to-back bachelors from Berkeley to Bowdoin.

This kind of thing flies because we all think we know which colleges are the good ones. But we don’t. Nobody knows! All we know is which colleges people say are good, and those people are in turn relying on what other people say. The much-hated US News and World Report is at least explicit about this—the biggest component of their college rankings is the “Peer Assessment,” which is where they send out a survey to university presidents that basically says, “I dunno, how good do you think Pomona is?” It’s one big ouroboros of hearsay, which sounds like the kind of thing Dante would have put in the fourth ring of hell.

It has to be this way, because how could you ever know how “good” a college is? Do an Undercover Boss-style sting where you sit in on Physics 101 and make sure the professor knows how to calculate angular momentum? Sneak into the dorms and measure whether the beds are really “twin extra long” or just “twin”? Stage an impromptu trolley problem in the quad and check whether the students would kill one person to save five?

(And besides, what is a “good college” good for? Neuroscience? Serving ceviche in the dining hall? Making it all go away when the son of a billionaire drives his Lambo into the lake?)

Judging quality is often expensive and sometimes impossible, and that’s why we resort to judging reputation instead. But it’s easy to feel like you’ve run a full battery of tests when in fact you’ve merely taken a straw poll. So when someone is like “This place has a great nursing program,” what they mean is “I heard someone say this place has a great nursing program,” and that person probably just heard someone else say it has a great nursing program, and if you trace that chain of claims back to its origin you won’t find anyone who actually knows anything—no one will be like “Oh yeah, I personally run bleeding through these halls all the time and I always get prompt and effective treatment.”4

HARD QUESTION: HOW SHOULD I FEEL ABOUT THIS? EASY QUESTION: CAN I IMAGINE SOMETHING BETTER OR WORSE ALMOST HAPPENING?

My friend Ricky once got tapped to do something very cool that I’m not allowed to talk about—basically, he was recruited to his profession’s equivalent of the NFL. Then, before Ricky even showed up to practice, and through no fault of his own, the team folded and his opportunity disappeared.

Ricky was bummed for weeks, and who wouldn’t be? But if you think about it for a second, Ricky’s disappointment gets a little more confusing. Ricky is right back where he was before he got the call, which is a pretty good place. Actually, he’s even better off—now he knows the bigwigs are looking at him, and that they think he’s got the juice. Sure, a good thing almost happened, and it’s too bad that it didn’t, but what about all the bad things that also could have happened: the team could never have thought about him at all, he could have shown up and broken his leg the first day, his teammates could have bullied him for being named after a character from a Will Ferrell movie, and so on, forever. There’s an infinite number of worse possible outcomes, so why think about this one and feel sad? I understand it’s “a human reaction,” Ricky, but...should it be?

Ricky essentially lived the real-life version of this old story from the psychologists Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky:

Of course, this is people guessing about how Mr. D and Mr. C would feel, not actual reports from the men themselves. But let’s assume that everybody’s right and Mr. C is the one kicking himself because he almost made it aboard. Why is it extra upsetting to miss your flight by 5 minutes rather than 30? C and D are both equally un-airborne. Neither of them budgeted enough time to get to the airport, and both of them have to buy new tickets. It’s easy to imagine how Mr. C could have arrived in time, but it’s also easy to imagine him wearing a hat or being a chef or doing the worm in the airport terminal, so what does it matter that there was some imagined universe where he got on his flight? That ain’t the universe we live in.

All that is to say: Ricky I’m so sorry for saying all this to you when you called me sobbing, please text me back.

MENTAL GRAPEFRUIT

Like every heuristic, attribute substitution is good 90% of the time, and the problems only arise when you use it in the wrong situation. Kinda like how grapefruit juice is normally a delicious part of a balanced breakfast, but if you’re taking blood pressure medications, it can kill you instead.

Fortunately, there’s an antidote to attribute substitution. In fact, there’s two. They are straightforward, free, and hated by all.

Use telekinesis

A foolproof way to stop yourself from making stupid judgments is to avoid judgment altogether. When someone asks you how the economy is doing, just go “Gosh, I haven’t the faintest.”

The problem with this strategy is it requires a superhuman level of mental fortitude—if you’re capable of pulling it off, you’ve probably already ascended to a higher plane. You know how in movies whenever someone is using a psychic power—say, telekinesis—and their face gets all strained and their eyes start bugging out and their nose starts bleeding, and then after they’ve, like, lifted a car off of their friend, they collapse from exertion? That’s what it feels like to maintain uncertainty. Conclusions come to mind quickly and effortlessly; keeping them out would require playing a perpetual game of mental whack-a-mole.

Even if we can never whack all the moles, though, it’s still good practice to whack a few. Keeping track of what you know and what you don’t know is just basic epistemic hygiene—it’s hard to think clearly unless you’ve done that first, just like it’s hard to do pretty much any job if you haven’t brushed your teeth for two years. Separating your baseless conjectures from your justified convictions is also a recipe for avoiding pointless arguments, since most of them boil down to things like “I like it when the president wears a blue tie” vs. “I like it when the president wears a red tie.”

Plus, maintaining the appropriate level of uncertainty prevents you from becoming a one-man misinformation machine. A couple weeks ago, somebody asked me “What was the first year that most homes in New York City had indoor plumbing?” I didn’t know the answer to this question, and yet somehow I still found myself saying, matter-of-factly, “I think, like, 1950.” Why did I do that? Why didn’t I just say, “Gosh, I haven’t the faintest”? Am I a crazy person? Did I think I could open my mouth and the Holy Spirit would speak through me, except instead of endowing me with the ability to speak in tongues, the Divine would bless me with plumbing trivia? I inserted one unit of bullshit into everyone’s heads for no reason at all, and on top that they now also think I’m some kind of toilet expert.

So we could all stand to cultivate a little more doubt. Ultimately, though, trying to prevent unwanted judgments by remaining uncertain is a bit like trying to prevent unwanted pregnancies by remaining abstinent: it works 100% of the time, until it doesn’t.

Wear clean underwear and eat a healthy breakfast

The other solution to attribute substitution is to make your judgments consciously and purposefully, rather than relying on whatever cockamamie shortcut your subconscious wants to take. When I taught negotiation, this was called “defining success,” and Day 1 was all about it. After all, how can you get what you want if you don’t know what you want?

Day 1 always flopped. Students hated defining success. It was like I was telling them to wear clean underwear and eat a healthy breakfast, and they were like “yeah yeah we’ve done all that.” But then it turned out most them were secretly wearing yesterday’s boxers and their breakfast was three puffs on a Juul.

One student, let’s call him Zack, came up to me after class one day, asking how he could make sure to get an A. “I know I haven’t turned in most of my assignments so far,” Zack admitted, “But that’s because I’ve been getting divorced and my two startups have been having trouble. Anyway, could I do some extra credit?”

I didn’t have the guts to tell Zack that trying to get an A in my class was a waste of his time, and he should instead focus on putting out the various fires in his life. Nor did I have the guts to tell him that he shouldn’t get an A in my class, because obviously he hadn’t learned the most important thing I was trying to teach him, which was to get his priorities straight.

I can’t blame Zack—it’s not like I ever reordered my life because someone showed me some PowerPoint slides. This is one of those situations where you can’t reach the brain through the ears, so perhaps this lesson is best applied straight to the skull instead. Supposedly Zen masters sometimes hit their students with sticks as a way of teaching them a lesson, like “Master, what’s the key to enlightenment?” *THWACK*. There’s something about getting a lump on your head that drives the point home better even than the kindest, clearest words. “Your question is so misspecified that it shows you need to rethink your fundamental assumptions” just doesn’t have the same oomph as a crack to the cranium.

Most of us don’t have the benefit of a Zen master, but fortunately the world is always holding out a stick for us so we can run headlong into it over and over. All we have to do is notice the goose-eggs on our noggins, which is apparently the hardest part. Zack’s marriage was imploding, his startups were going under, he was flunking a class that was kinda designed to be un-flunkable—this was a guy who had basically pulped his skull by sprinting full-tilt into the stick, and yet he was still saying to himself, “Maybe I just need to run into the stick harder.”

I don’t know what more Zack needs, but for me, if I’m gonna stop running into the stick, I have to realize that I’m the kind of person who will, by default, spend 90 minutes deciding which movie to watch and 9 seconds deciding what I want out of life. I gotta ask myself: if I’m busting my ass from sunup to sundown, what am I hoping for in return? A thoroughly busted ass?

It feels stupid to ask myself these questions, because the answers either seem obvious or like foregone conclusions, but they aren’t. It’s like I’m in one of those self-driving jeeps from Jurassic Park and I’m heading straight toward a pack of Velociraptors and I’m just like, “Welp, I guess there was no way to avoid this,” as if I didn’t choose to accept an eccentric old man’s invitation to a dinosaur island.

CAR KEYS, YUM

The OG psychologist William James famously claimed that babies, because they have no idea what’s going on around them, must experience the world as a “blooming, buzzing confusion.” As they grow up and learn to make sense of things, the blooming and buzzing subside.

This idea is intuitive, beautiful, and—I suspect—wrong. Confusion is a sophisticated emotion: it requires knowing that you don’t know something. That kind of meta-cognition is difficult for a grownup, and it might be impossible for someone who still can’t insert their index finger into their own nose. Whenever I hang out with a baby, that certainly seems true—I’m confused about what to do with them, while they’re extremely certain that my car keys belong in their mouth.

Confusion, like every emotion, is a signal: it’s the ding-a-ling that tells you to think harder because things aren’t adding up. That’s why, as soon as we unlock the ability to feel confused, we also start learning all sorts of tricks for avoiding it in the first place, lest we ding-a-ling ourselves to death. That’s what every heuristic is—a way of short-circuiting our uncertainty, of decreasing the time spent scratching our heads so we can get back to what really matters (putting car keys in our mouths).

I think it’s cool that my mind can do all these tricks, but I’m trying to get comfortable scratching my head a little longer. Being alive is strange and mysterious, and I’d like to spend some time with that fact while I’ve got the chance, to visit the jagged shoreline where the bit that I know meets the infinite that I don’t know, and to be at peace sitting there a while, accompanied by nothing but the ring of my own confusion and the crunch of delicious car keys.

Technically, there is also no Nobel Prize for economics. There is only the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, established in 1968. In 2005, one of the living Nobels described the prize as “a PR coup by economists to improve their reputation,” which of course it is, much like the Nobel Prizes are themselves a PR coup by a guy who got rich selling explosives. Anyway, this is a helpful fact to have in your pocket if you’re ever hanging out with economists and you’d like to make things worse.

Prediction: when they reboot The Three Stooges in 2071, their names will be Doge, Bonk, and Floki.

All names have been changed to protect the innocent (it’s me, I am the innocent).

Okay actually on that note I think Brandeis University has a great EMT program, or at least it did c. 2012, which is when I went there on an improv tour and got gastroenteritis in the middle of the show and had to flee from the stage to the bathroom, puking all the way. The EMTs were there in seconds, and although none of them could help me, they were all very nice. So if you’re ever going to have a medical emergency, make sure your EMTs went to Brandeis roughly 13 years ago.

I'm feeling pretty smug right now.

I frequently say "I don't know, but I can research that" - which is both antidotes rolled into one. Also, researching things is more fun than not knowing them.

Re. the other stuff: I've also been good at not comparing myself to others because I long ago actually realized it was making me unhappy. In particular, I was comparing myself to people who were good at things I didn't even want to succeed at, like going to the gym regularly.

And in my 40 years in the corporate world I can honestly I very rarely worked anywhere near as hard as my colleagues did, or at least pretended to do, and only put in long hours when I got caught up in something I really enjoyed. Somewhere around the age of 40 I realized that I could get great performance reviews while still only working hard about 50% of the time, goofing off for the rest, and going home at five. I suspect that a big part of that was identifying the meaningless busywork, and putting the least amount of effort as possible into it. I was always astonished at colleagues spending hours on a presentation that we all knew was practically a throwaway.

FWIW my theory is that a lot of people in corporate jobs, consciously or subconsciously, recognize that a great deal of what they do has results that are practically impossible to measure, if indeed they have any results at all, so instead of measuring their corporate success by what they achieve, they measure it by how exhausted they feel.

Superb writing! The world would be a much better place if we could all be a bit more comfortable not knowing.

From Rebecca Solnit: "In the spaciousness of uncertainty, there is room to act."