Secrets of the ancient memelords

OR: pedants 'n' pinheads

I say this with tremendous respect: it’s kinda surprising that the three largest religions in the world are Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism.

None of them are very sexy or fun, they come with all kinds of rules, and if they promise you any happiness at all, it’s either after you’re dead, or it’s the lamest kind of happiness possible, the kind where you don’t get anything you want but you supposedly feel fine about it. If you were trying to design a successful religion from scratch, I don’t think any of these would have made it out of focus groups. “Yeah, uh, women 18 to 34 years old just aren’t resonating with the part where the guy gets nailed to a tree.”

Why, in the ultimate meme battle of religions, did these three prevail? Let’s assume for the sake of argument that it’s not because they have the divine on their side. (Otherwise, God appears to be hedging his bets by backing multiple religions at once.)

Obviously there’s a lot of historical contingency here, and if a couple wars had gone the other way, we might have a different set of creeds on the podium. But I think each of these mega-religions has something in common, something we never really talk about, maybe because we don’t notice it, or maybe because it’s impolite to mention—namely, that they all have a brainy version and a folksy version.

If you’re the scholarly type, Christianity offers you Aquinas and Augustine, Islam has al-Ash’ari and al-Ghazali, Hinduism has Adi Shankara and Swami Vivekananda, etc. But if you don’t care for bookish stuff, you can also just say the prayers, sing the songs, bow to the right things at the right time, and it’s all good. The guy with the MDiv degree is just as Christian as the guy who does spirit hands while the praise band plays “Our God Is an Awesome God”.

It’s hard to talk about this without making it sound like the brainy version is the “good” one, because if we’re doing forensic sociology of religion, it’s obvious which side of the spectrum we prefer. But brainy vs. folksy is really about interest rather than ability. The people who favor the brainier side may or may not be better at thinking, but this is the thing they like thinking about.

More importantly, the brainy and the folksy sides need each other. The brainy version appeals to evangelists, explainers, and institution-builders—people who make their religion respectable and robust. The folksy version keeps a religion relevant and accessible to the 99.9% of humanity who can’t do faith full-time—people who might not be able to name all the commandments, but who will still show up on Sunday and put their dollars in the basket. The brainy version fills the pulpits; the folksy version fills the pews.1

Naturally, brainy folks are always a little annoyed at folksy folks, and folksy folks are always a little resentful of brainy folks. It’s tempting to split up: “Imagine if we didn’t have to pander to these know-nothings”/”Imagine if we didn’t have to listen to these nerds!” But a religion can start wobbling out of control if it tilts too far toward either its brainy yin or its folksy yang. Left unchecked, brainy types can become obsessed with esoterica, to the point where they start killing each other over commas. Meanwhile, uncultivated folksiness can degenerate into hogwash and superstition. Pure braininess is one inscrutable sage preaching to no one; pure folksiness is turning the madrasa into a gift shop.

SPLITSVILLE

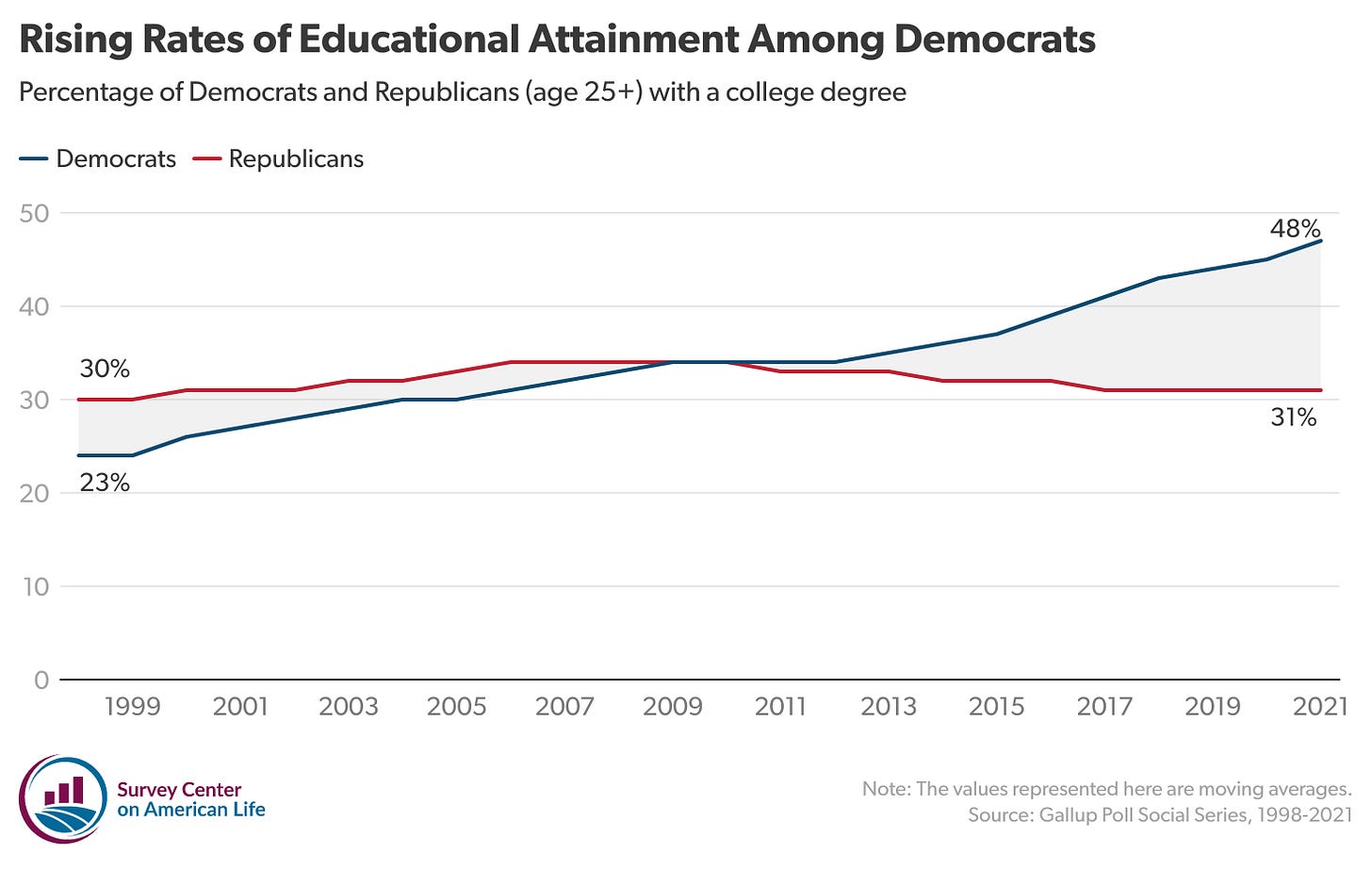

Here’s why I bring all this up: we’ve got a big brainy/folksy split on our hands right now:

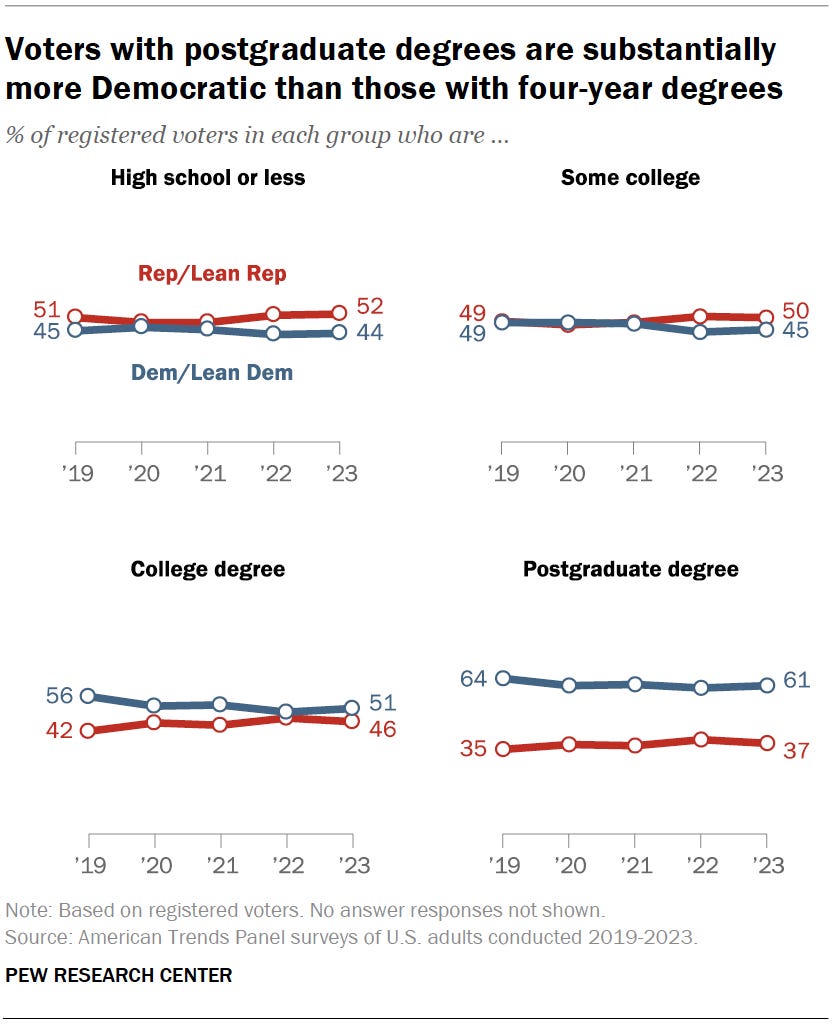

That divide is biggest at the highest level of education:

To think clearly about this situation, we have to continue resisting the temptation to focus on which side is “correct”. And we have to avoid glossing the divide as “Democrats = smart, Republicans = dumb”—both because going to college doesn’t mean you actually know anything, and because intelligence is far more complicated than we like to admit.

I think this divide is better understood as cultural rather than cognitive, but it doesn’t really matter, because separating the brainy and the folksy leaves you with the worst version of each. This is one reason why politics is so outrageous right now—only a sicko would delight in the White House’s Studio Ghibli-fied picture of a weeping woman being deported, and only an insufferable scold would try to outlaw words like “crazy”, “stupid”, and “grandfather” in the name of political correctness. It’s not hard to see why most people don’t feel like they fit in well with either party. But as long as the folksy and brainy contingents stay on opposite sides of the dance floor, we can look forward to a lot more of this.

Bifurcation by education is always bad, but it’s worse for the educated group, because they’ll always be outnumbered. You simply cannot build a political coalition on the expectation that everybody’s going to do the reading. If the brainy group is going to survive, it has to find a way to reunite with the folksy.

So maybe it’s worth taking some cues from the most successful ideologies of all time, the ones that have kept the brainy and folksy strains intertwined for thousands of years. I don’t think politics should be a religion—I’m not even sure if religion should be a religion—but someone’s gonna run the country, and as long as we’ve got a brainy/folksy split, we’ll always have to choose between someone who is up their own ass, and someone who simply is an ass.

As far as I can see, the biggest religions offer two strategies for bridging the divide between the high-falutin and the low-falutin. Let’s call ‘em fractal beliefs and memetic flexibility.

DURKHEIM TO THE BACK, PLEASE

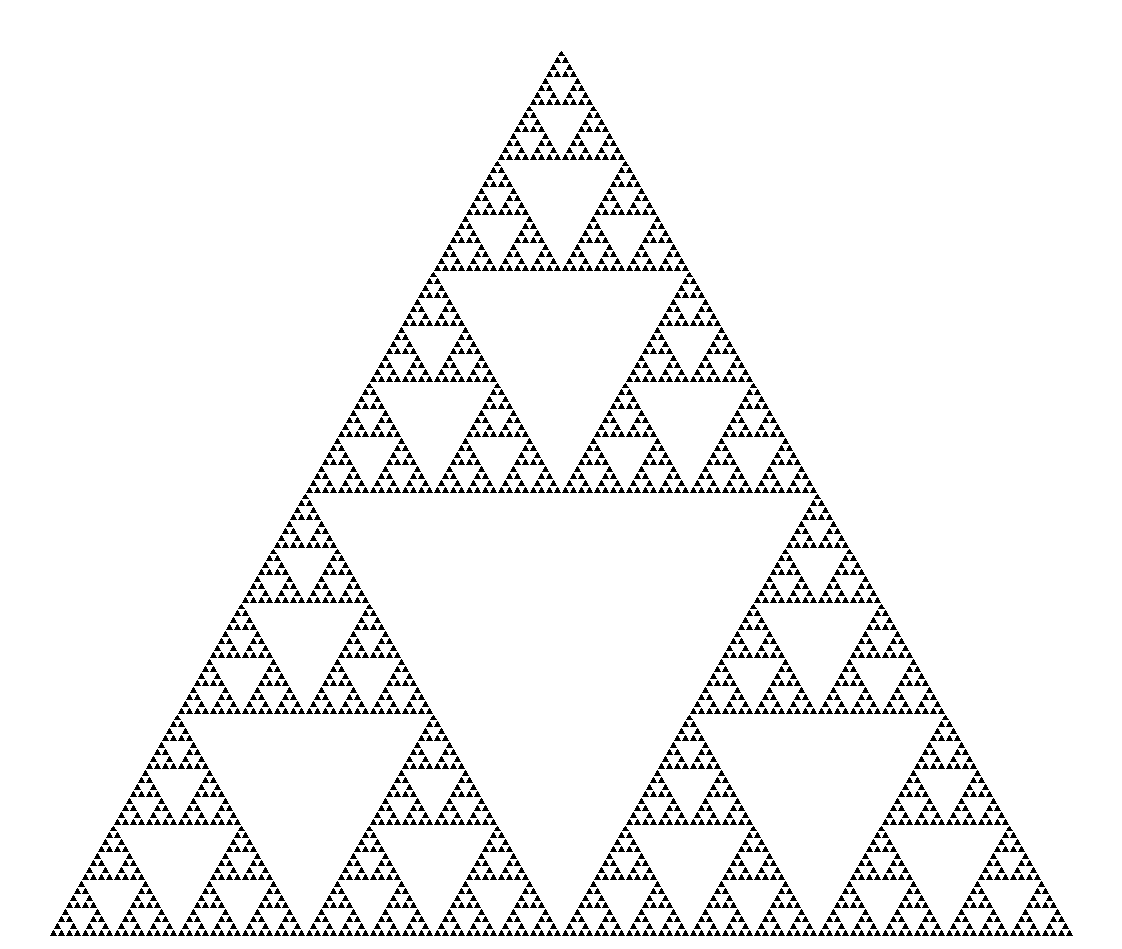

The shape below is a fractal, a triangle made up of triangles. Look at it from far away and you see one big triangle; look at it close up and you see lots of little triangles. It’s triangles all the way down.

The most successful ideologies have similarly fractal beliefs: you get the same ideas no matter how much you zoom in or out. If a Christian leans more into their faith—if they read the Bible cover to cover, go to church twice a week, and start listening to sermons on the way to work—they don’t suddenly transform into, say, a Buddhist. They’re just an extra-enthusiastic Christian with extra-elaborated beliefs. This is a critical feature: if your high-devotion and low-devotion followers believe totally different things, eventually they’re gonna split.

If the brainy tribe is to survive, then, it’s gotta fractal-ize its beliefs. That means generating the simplest versions of your platform that is still true. For example, many brainy folks want to begin arguments about gender by positing something like “gender is a social construct”, and right out the gate they’re expecting everyone to have internalized like three different concepts from sociology 101. Instead, they should start with something everybody can understand and get on board with, like “People’s opportunities in life shouldn’t depend on their private parts”. Making your arguments fractal doesn’t require changing their core commitments; it just means making each step of the argument digestible to someone who has no inclination to chew. If you’re gotta bring up Durkheim, at least put him last.

Brainy folks hate doing this. They’d much prefer to produce ever-more-exquisite versions of their arguments because, to borrow some blockchain terminology, brainy people operate on a proof-of-work system, where your standing is based on the effort you put in. That’s why brainy folks are so attracted to the idea that your first instincts cannot be right, and it’s why their beliefs can be an acquired taste. You’re supposed to struggle a bit to get them—that’s how you prove that you did your homework.

(Only the brainy tribe would, for instance, insist that you need to “educate yourself” in order to participate in polite society, and that no one should be expected to help you with this.)

It would be convenient for this analogy if folksy types operated on a proof-of-stake system (which is the other way blockchains can work), but they don’t, really. They don’t operate on proof of anything—the whole concept of proof is dubious to them. You don’t need to prove the obvious. That might sound dumb, and it often is. But sometimes it’s a useful counterweight: sometimes your first instinct is indeed the right one, and you can think yourself into a stupider position.

Regardless, demanding proof-of-work is always going to tilt the playing field in favor of the other side. A liberal friend of mine was recently lamenting that liberals have all the complicated-but-true positions while conservatives have all the easy-but-wrong positions. She acted like this was the natural end state of things; too bad, so sad, I guess the stupid shall inherit the Earth!

This sounds like a cop-out to me. If you can’t find an accessible way to express your complicated-but-true beliefs, maybe they aren’t actually true, or maybe you’re not trying hard enough. Of course, it takes a lot of thought to make a convoluted idea more intuitive—if only there were some people who liked thinking!

LET THEM DRIVE HUMMERS

Big religions have a healthy dose of memetic flexibility: while their central tenets are firm, the rest of their belief systems can bend to fit lots of different situations.

For example, why are there four gospels? You’d think it would be a liability to have four versions of the same story floating around, especially when they’re not perfectly consistent with each other. There are disagreements about the name of Jesus’ paternal grandfather, the chronology of his birth, his last words, and uh, whether you’re supposed to take a staff with you when you go off to proselytize (Matthew and Luke say yes, but Mark says no way). This kind of thing is very embarrassing when you’re trying to convince people that you have the inerrant word of God. Wouldn’t it make more sense to smush all these accounts together into one coherent whole?

Syriac Christians did exactly that in the second century AD: it was called the Diatessaron. And yet, despite its cool name, it never really caught on and eventually died out. Nobody even tried that hard to suppress it as a heresy. I mean, if no one claims that your book is the work of the devil, do you even exist??

Maybe the harmonized gospel never went viral because four gospels, inconsistencies and all, are better than one. Each gospel has its own target audience: you’ve got Matthew for the Jews, Luke for the ladies and the Romans, John for the incense-and-crystals crowd, and Mark for the uh...all those Mark-heads out there, you know who you are. Having four stories with the same moral but different details and emphases gives you memetic flexibility without compromising the core beliefs.

Brainy folks could learn a lot from this. For instance, there’s a certain kind of galaxy-brained doomer who thinks that the only acceptable way to fight climate change is to tighten our belts. If we can invent our way out of this crisis with, say, hydrogen fuel cells or super-safe nuclear reactors, they think that’s somehow cheating. We’re supposed to scrimp, sweat, and suffer, because the greenhouse effect is not just a fact of chemistry and physics—it’s our moral comeuppance. In the same way that evangelical pastors used to say that every tornado was God’s punishment for homosexuality, these folks believe that rising sea levels are God’s punishment for, I guess, air conditioning.

This kind of small-tent, memetically inflexible thinking is a great way to make your political movement go extinct. But if you’re willing to be a little open-minded about how, exactly, we prevent the Earth from turning into a sun-dried tomato, you might actually succeed. Imagine if we could suck the carbon out of the atmosphere and turn it into charcoal for your Fourth of July barbecue. Imagine if electricity was so cheap and clean that you could drive your Hummer from sea to shining sea while causing net zero emissions. Imagine genetically engineered cows that don’t fart. That’s a future far more people can get behind, both literally and figuratively.

PEDANTS ‘N’ PINHEADS

A few months ago, I ran into an old classmate at the grocery store—let’s call him Jay. He was a bit standoffish at first, and I soon found out why: Jay works in progressive politics now, and he was sussing me out to see whether I had become a right-wing shill since graduation, which is what some of our mutual acquaintances have done. Once he was satisfied I wasn’t trying to follow the well-trod liberal-loser-to-Fox-News-provocateur track, he warmed up. “I unfriended all the conservatives I know. I don’t even talk to moderates anymore,” Jay said, as if this was the most normal thing in the world. I didn’t want to get into it with him in the cereal aisle, but I wanted to know: what is his plan for dealing with the ongoing existence of his enemies? If he ignores them, they’ll....what? Give up? Fill their pockets with stones and wade into the ocean?

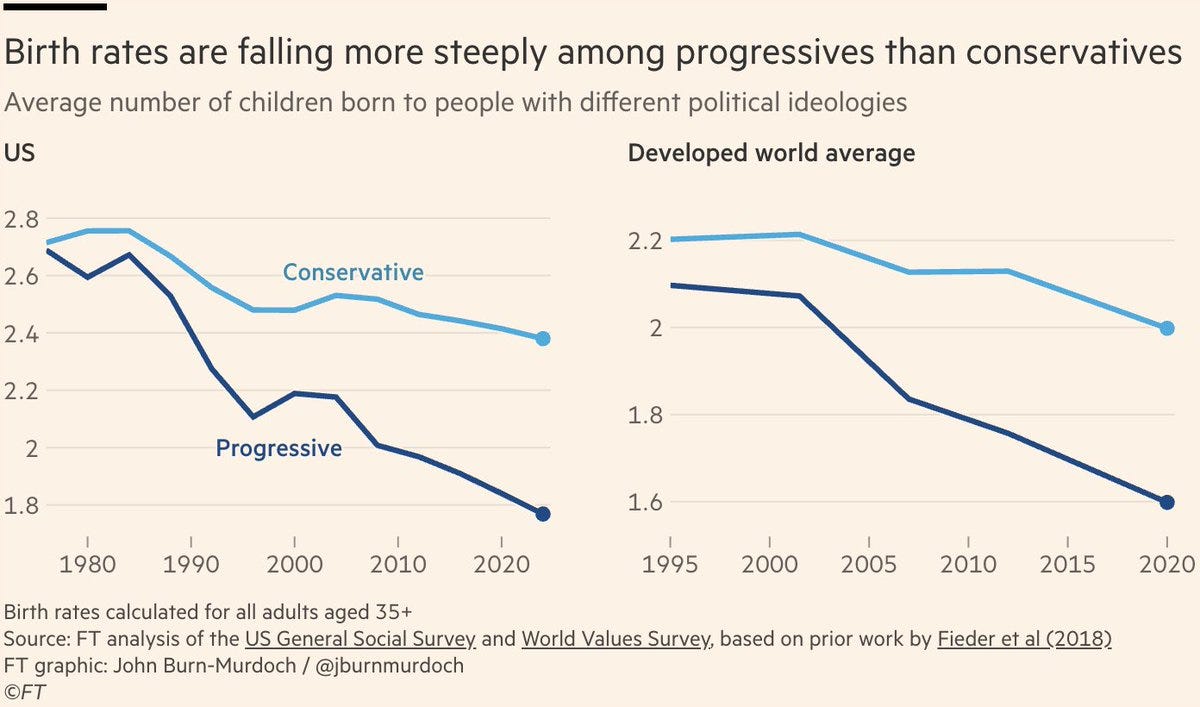

Apparently, Jay has decided that his side should lose. There are only three ways that an idea can gain a greater share of human minds: conquest, conversion, or conception. I hope we can all agree that killing is off the table, so that leaves changing minds and makin’ babies. It seems to me that progressives have largely given up on both.2

Obviously, I don’t think people should have kids just to thicken the ranks of their political party, nor do I want proselytizing progressives on every street corner. But if you’re serious about your political beliefs, you should have some plausible theory of how they’re going succeed in the future. That means making it easy to believe the things you think are true, and it means trying to appeal to people who don’t already agree with you.

Most of all, it means participating in the world in a way that makes people want to join you. That’s why there are 5.5 billion Christians, Muslims, and Hindus—those religions offer people something that earns their continued devotion, whether those people want to think really hard about their faith or not. People aren’t gonna show up to Jay’s church if it’s all pulpit and no pew.

There are always going to be political cleavages, and there should be. The ideal amount of polarization is not zero. (When everybody’s on the same page, we groupthink ourselves into doing stupid things like, you know, invading two countries in two years.) Running a country is the greatest adversarial collaboration known to man, and it only works when both sides bring their best ideas. To do that, we need each party to have a fully integrated brainy and folksy contingent; some people plumbing the depths, other people keeping the boat anchored. Otherwise, we end up with parties that are defined either by their pointy-headed pedants or their pinheaded reactionaries.

“I must study Politicks and War,” John Adams famously wrote, “that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy”:

My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.

I appreciate Adams’ aspirations, but I disagree with his order of operations. Politics is not a science set apart from all others. Good governance requires good thinking, and that means drawing on every ounce of our knowledge, no matter how far-flung. Right now, I think we could stand to learn a thing or two from the ancient memelords who created our modern religions. Otherwise, yes, a world where we’re more interested in painting and poetry than we are politics—that sounds great. I think we know the way there. We just have to grab our walking sticks.

Many people assume this arrangement has broken down, and that highly educated people have all ditched their churches and become atheists. In fact, more-educated people are more likely to attend religious services.

Really good analogies in here. You use memable ideas to get your point across about memeable ideas - how meta of you.

I think that's why the right has reacted so strongly to the left in the past ten years - the left became a party of pure theory, pure thought, pure arrogant moralizing, and the right felt that the whole country had become all pulpit. As you said, they stopped attending. They felt abandoned.

The best vehicle for culture isn't moralizing or "expertise" - it's stories. And that's why the folksy side doesn't like when it hears a negative story about itself. It needs a good story to live up to, not one where it's the villain and needs to be punished. Who the hell would want to hear that story?

Well, this one doesn't land well, largely because your starting assumptions ignore a--to use the technical term--whole lotta stuff.

Yes, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism are the big three in terms of numbers, but you make a big jump in the reasons for that. Christianity made the leap from a charismatic leader to a full-fledged religion/state with Constantine (see Constantine's Sword for the deep dive). That gave it the structure and numbers that enabled it to grow. It is also a universalizing religion, which means that converting others is part of its DNA.

Islam is also universalizing and melds a charismatic leader to an existing (albeit very different) societal structure.

So, irrespective of a compelling narrative and set of core beliefs, both those religions are deeply investing in growing. And were not shy about using force to do so.

Hinduism is another story. It is an ethnic religion that exists in a particular region with a particular people that had, in effect, thousands of years to develop organically. (I will note that it is one of four Dharmic religions, the others being Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.)

So lumping the three together on the basis of size ignores the differences in geography that led to the relative isolation of Southeast Asia.

Maintaining core values, ethics, practices while still having the flexibility to change is a necessity for any society/religion to survive for very long. Both Durkheim's definition of religion and Ninian Smart's more extended version enable a better analysis of what makes societies succeed over time or fail.

Finally, if having both a compelling and simple story along with lots of intellectual chatter led to large numbers of adherents, Judaism would win hands down. The Jewish core narrative of slavery to freedom is compelling and has been used to inspire enslaved people in the US and liberation theology in South America. And if you want intellectual debate--there's a reason people say "two Jews, three opinions." And yet, world Jewish population is all of 15 million.