The drug that taught me how much I should suffer

OR: grindset and bedrot

All of us, whether we realize it or not, are asking ourselves one question over and over for our whole lives: how much should I suffer?

Should I take the job that pays more but also sucks more? Should I stick with the guy who sometimes drives me insane? Should I drag myself through an organic chemistry class if I means I have a shot at becoming a surgeon?

It’s impossible to answer these questions if you haven’t figured out your Acceptable Suffering Ratio. I don’t know how one does that in general. I only know how I found mine: by taking a dangerous, but legal, drug.

DIARY OF A PIMPLY KID

I’ve always had bad skin. I was that kinda pimply kid in school—you know him, that kid with a face that invites mild cruelty from his fellow teens.1 I did all sorts of scrubs and washes, to little avail. In grad school, I started getting nasty cysts in my earlobes that would fill with pus and weep for days and I decided: enough. Enough! It’s the 21st century. Surely science can do something for me, right?

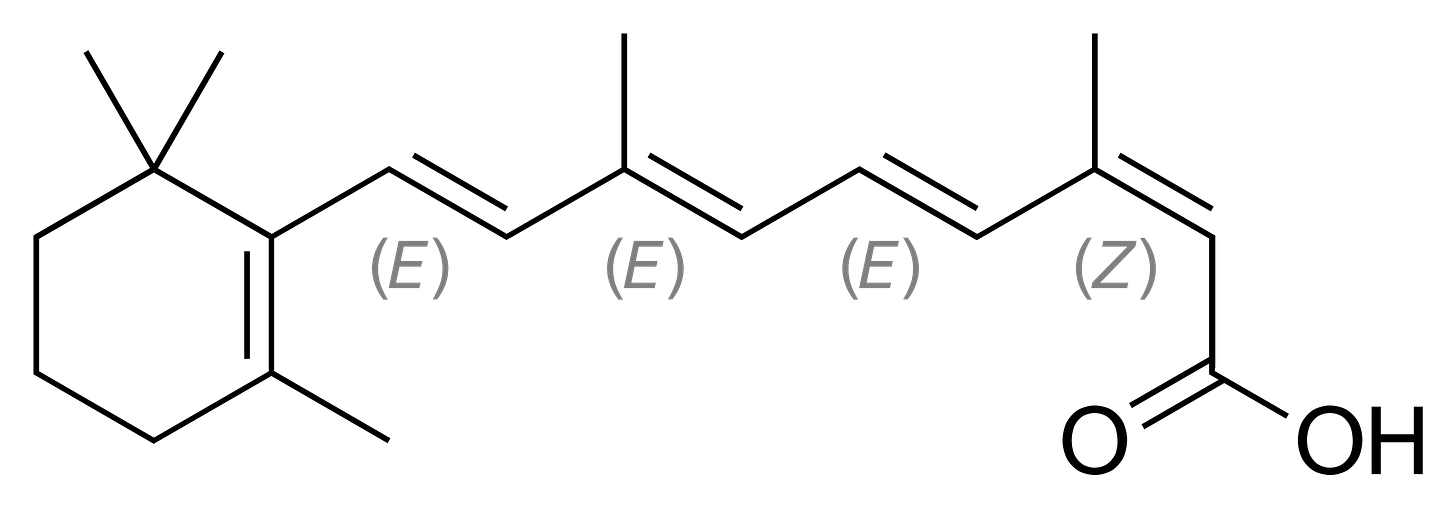

And science could do something for me: it could offer me a drug called Accutane. Well, it could offer me isotretinoin, which used to be sold as Accutane, but the manufacturers stopped selling it because too many kids killed themselves.

See, Accutane has a lot of potential side effects, including hearing loss, pancreatitis, “loosening of the skin”, “increased pressure around the brain”, and, most famous of all, depression, anxiety, and thoughts of suicide and self-injury. In 2000, a Congressman’s son shot himself while he was on Accutane, which naturally made everyone very nervous. My doctor was so worried that she offered to “balance me out” with an antidepressant before I even started on the acne meds. I turned her down, figuring I was too young to try the “put a bunch of drugs inside you and let ‘em duke it out” school of pharmacology.

But her concerns were reasonable: Accutane did indeed make me less happy. Like an Instagram filter for the mind, it deepened the blacks and washed out the whites: sad things felt a little sharper and happy things felt a little blunted. I was a bit quicker to get angry, and I was more often visited by the thought that nothing in my life was going well—although, as a grad student, I was visited fairly often by that thought even in normal times. It wasn’t the kind of thing I noticed every day. But occasionally, when I was, say, struggling to get some code to work, I’d feel an extra, unfamiliar tang of despair, and I’d go, “Accutane, is that you?”

The drugs also made my skin like 95% better. It was night and day—we’re talking going from Diary of a Pimply Kid to uh, Diary of a Normal Kid. That wonderful facial glow-up that most people experience as they exit puberty, I got to experience that same thing in my mid-20s. Ten years later, I’m still basically zit-free.

I didn’t realize it at first, but I had found my Acceptable Suffering Ratio. Six months of moderate sadness for a lifetime of clear skin? Yes, I’ll take that deal. But nothing worse than that. If the suffering is longer or deeper, if the upside is lower or less certain: no way dude. I’m looking for Accutane-level value out of life, or better.

That probably sounds stupid. It is stupid. And yet, until that point, I don’t think I was sufficiently skeptical of the deals life was offering me. Whenever I had the chance to trade pain for gain, I wasn’t asking: how bad, for how long, and for how much in return? I literally never wondered “How much should I suffer to achieve my goals?” because the implicit answer was always “As much as I have to”.

SISYPHUS AND HERCULES

My oversight makes some sense—I was in academia at the time, where guaranteed suffering for uncertain gains is the name of the game. But I think a lot of us have Acceptable Suffering Ratios that are way out of whack. We believe ourselves to be in the myth of Sisyphus, where suffering is both futile and inescapable, when we are actually in myth of Hercules, where heroic labors ought to earn us godly rewards.

For example, I know this guy, call him Omar, and women are always falling in unrequited love with him. They’re gaga for Omar, but he’s lukewarm on them, and so they make a home for him in their hearts that he only ever uses as a crash pad. I don’t know these women personally, but sometimes I wish I could go undercover in their lives as like their hairdresser or whatever just so I could tell them: “It’s not supposed to feel like this.” This pining after nothing, this endless waiting and hoping that some dude’s change of heart will ultimately vindicate your years of one-sided affection—that’s not the trade that real love should ask of you.

Real love does bring plenty of pain: the angst of being perceived exactly as you are, the torment of confronting your own selfishness, the fear of giving someone else the nuclear detonation codes to your life. But if you can withstand those agonies, you will be richly rewarded. Omar’s frustrated lovers have this romantic notion that love is a burden to be borne, and the greater the burden, the greater the love. When a love is right, though, it’s less like heaving a legendary boulder up a mountain, and more like schlepping a picnic basket up a hill—yes, you gotta carry the thing to and fro, and it’s a bit of a pain in the ass, but in between you get to enjoy the sunset and the brie.

READ ‘EM AND WII’P

Our Acceptable Suffering Ratios are most out of whack when it comes to choosing what to do with our lives.

Careers usually have a “pay your dues” phase, which implies the existence of a “collect your dues” phase. In my experience, however, the dues that go in are no guarantee of the dues that come back out. There is no cosmic, omnipotent bean-counter who makes sure that you get your adversity paid back with interest. You really can suffer for nothing.

If you’re staring down a gauntlet of pain, then, it’s important to peek at the people coming out the other side. If they’re like, “I’m so glad I went through that gauntlet of pain! That was definitely worth it, no question!” then maybe it’s wise to follow in their footsteps. But if the people on the other side of the gauntlet are like, “What do you mean, other side of the gauntlet? I’m still in it! Look at me suffering!”, perhaps you should steer clear.

Psychologists refer to this process of gauntlet-peeking as surrogation. People are hesitant to do it, however, I think because it feels so silly. If you see people queuing up for a gauntlet of pain, it’s natural to assume that the payoff must be worth the price. But that’s reasoning in the wrong direction. We shouldn’t be asking, “How desirable is this job to the people who want it?” That answer is always going to be “very desirable”, because we’ve selected on the outcome. Instead, the thing we need to know is, “How desirable is this job to the people who have it?”

It turns out the scarcity of a resource is much more potent in the wanting than it is in the having. I had a chance to learn this lesson about twenty years ago, when the stakes were far lower, but I declined. Back then, I thought the only barrier between me and permanent happiness was a Nintendo Wii. I stood outside a Target at 5am in the freezing cold for the mere chance of buying one, counting and re-counting the people in front of me, desperately trying to guess whether there would be enough Wiis to go around, my face going numb as I dreamed of the rapturous enjoyment of Wii Bowling.

I didn’t realize that, by the time I got home, the most exciting part of owning a Wii was already over. When I strapped on my Wii-mote, there was not a gaggle of covetous boys salivating outside my window, reminding me that I was having an enviable experience. It turns out that what makes a game fun is its quality, not its rarity.

If I had understood that obvious fact at the time, I probably wouldn’t have wasted so many hours lusting after a game console, caressing pictures of nunchuck attachments in my monthly Nintendo Power, calling Best Buys to pump them for information about when shipments would arrive, or guilting my mom into pre-dawn excursions to far-flung electronics stores.

Post-Accutane, though, I think I got better at spotting situations like these and surrogating myself out of them. When I got to be an upper-level PhD student, I would go to conferences, look for the people who were five years or so ahead of me, and ask myself: do they seem happy? Do I want to be like them? Are they pleased to have exited the gauntlet of pain that separates my life and theirs? The answer was an emphatic no. Landing a professor position had not suddenly put all their neuroses into remission. If anything, their success had justified their suffering, thus inviting even more of it. If it took this much self-abnegation, mortification, and degradation to get an academic job, imagine how much you’ll need for tenure!

SET ME FREE AND I’LL DREAM MYSELF A CAGE

I think our dysfunctional relationship with suffering is wired deep in our psyches, because it shows up even in the midst of our fantasies.

I’ve gotten back into improv recently, which has reacquainted me with a startling fact. An improv scene could happen anywhere and be about anything—we’re lovers on Mars! We’re teenage monarchs! We’re Oompa-Loompas backstage at the chocolate factory! And yet, when given infinite freedom, what do people do? They shuffle out on stage, sit down at a pretend computer, start to type, and exclaim, “I hate my job!”

It’s remarkable how many scenes are like this, how quickly we default to criticizing and complaining about the very reality that we just made up.2 A blank stage somehow turns us into heat-seeking missiles for the situations we least want to be in, as if there’s some unwritten rule that says that when we play pretend, we must imagine ourselves in hell.3

I’m not usually this kind of psychologist, but I can’t help but see these scenes as a kind of reverse Rorschach test. When allowed to draw whatever kind of blob we want, we draw one that looks like the father who was never proud of us. “Yep, that’s it! That’s exactly the thing I don’t like!”

I don’t think that instinct should be squelched, but it should be questioned. Is that the thing you really want to draw? Because you could also draw, like, a giraffe, if you wanted to. Or a rocket ship. Or anything, really. The things that hurt you are not owed some minimum amount of mental airtime. If you’re going to dredge them up and splatter them across the canvas, it should be for something—to better understand them, to accept them, to laugh at them, to untangle them, not to simply stand back and despise them, as if you’re opening up a gallery of all the art you hate the most.

CHICK LIT

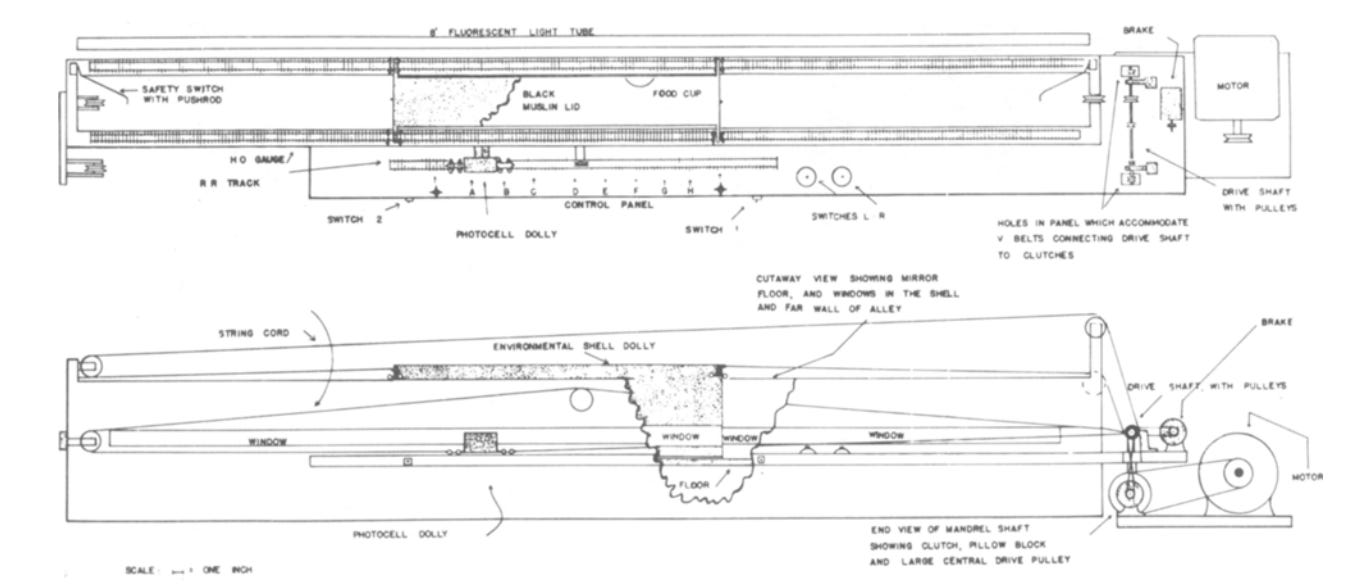

In 1986, a psychologist named Wayne Hershberger played a nasty trick on some baby chickens. He rigged up a box with a cup of food suspended from a railing, and whenever the chicks would try to approach the cup, an apparatus would yank it out of their reach. If the chicks walked in the opposite direction, however, the same apparatus would swing the cup closer to them. So the only way for the chicks to get their dinner was for them to do what must have felt like the dumbest thing in the world: they had to walk away from the food. Alas, most of the chicks never learned how to do this.

I think many humans never learn how to do this, either. They assume that our existence is nothing more than an endless lurching in the direction of the things you want, and never actually getting them. Life is hard and then you die; stick a needle in your eye!

There are people with the opposite problem, of course: people who refuse to take on any amount of discomfort in pursuit of their goals, people who try not to have any goals in the first place, for they only bring affliction. It’s a different strategy, but the same mistake. These two opposing approaches to life—call them grindset and bedrot—both assume that the ratio between pain and gain is fixed. The grindset gang simply accepts every deal they’re offered, while the bedrot brigade turns every deal down.

Neither camp understands that when you get your Suffering Ratio right, it doesn’t feel like suffering at all. The active ingredient in suffering is pointlessness; when it has a purpose, it loses its potency. Taking Accutane made me sad, yes, but for a reason. The nearly-certain promise of a less-pimply face gave meaning to my misery, shrinking it to mere irritation.

Torturing yourself for an unknown increase in the chance that you’ll get some outcome that you’re not even sure you want—yes, that should hurt! That’s the signal you should do something else. When your lunch is snatched out of your grasp for the hundredth time in a row, perhaps you should see what happens when you walk away instead.

Apparently kids these days cover up their pimples with little medicated stickers, rather than parading around all day with raw, white-headed zits. This is a terrific technological and social innovation, and I commend everyone who made it happen.

Perhaps Trent Reznor was thinking of improv comedy when he wrote the lyric:

You were never really real to begin with

I just made you up to hurt myself

You might assume that improv is a good place to work out your demons, until you think about it for a second and realize that it basically amounts to deputizing strangers into doing art therapy with you. So while I’ve never personally witnessed someone conquer their traumas through improv comedy, I have witnessed many people spread their traumas to others.

Wonderful observation. I really appreciate this perspective.

Recently, I'd taken some time away from my career to focus on my fiction writing. I came to this project with the belief that it had to be full of suffering, modeled after what I'd seen in other artists. But, slowly, I'm learning that difficult balance between pleasure and suffering. With any endeavor, we need to work past the preconceptions that our society fills us with: what should work look like? How should we feel doing it? How should we approach it? How much should we suffer?

When we approach these questions and start to think for ourselves--how we want our lives to look, the texture, the feeling, the amount of suffering, the way we approach our work and setbacks, we can then choose to work in our own unique way. Some suffering is necessary; however, the amount of suffering I have created for myself in the past few months is due to the belief that I had to work a certain way. I believed I needed to struggle hard to create good fiction--but I only did that because THAT'S the way that I'd seen creativity depicted in the our culture.

So, in addition to choosing our own amount of suffering, we must be careful about the narratives that we formulate our lives around. If we admire the starving artist model, the person who suffers severely in order to create, and who is in constant pain when he is not creating--putting himself into a cycle of suffering in which the benefits do not outweigh the drawbacks, then of course we're going to be miserable. Following this model, I was miserable! I was looking up to the WRONG people. I revered the wrong stories. I used the wrong life model.

Thank you for sharing this wonderful article. I hope others find as much value in it as I have!

I discovered my Acceptable Suffering Ratio when I started taking a GLP-1 to mitigate diabetes. A day or two every few weeks of nausea and gastrointestinal distress in exchange for living past seventy--worth it.