My latest paper, The Illusion of Moral Decline, was published in Nature today.1

I’m proud of this project. It was my PhD dissertation, and some of the ideas in the paper have been percolating in my head since college. I’m glad to finally have it outside my skull so that other people can take a look.

Dan Gilbert (my coauthor) and I spent a long time making this paper readable, and we spent a considerable amount of money making it open-access, so you can read it even if you don’t pay for a Nature subscription. But like any paper written for a scientific journal, it’s long, it's got lots of numbers in it, and it has some bits that we inserted to placate reviewers and editors. Basically, if you want to hear the full album, read the paper. But if you want just a couple hit singles, let me spin ‘em for ya right here.

PLEASE ALLOW ME TO WATCH PADDINGTON 2 IN PEACE

This paper was born out of spite. For my whole life, I’ve listened to people bemoan the demise of human goodness. “Used to be you could trust a man’s word,” “Back in the day, you didn’t have to lock your doors at night,” “People don’t care for one another anymore,” etc.

This drives me nuts, because people are often wrong about how the present differs from the past. In another paper, I asked people to estimate how public opinion had shifted over time on a bunch of different issues, and they were really bad at it. Not just randomly bad, like a bunch of people throwing darts at a board and most of them missing the bullseye. They were biased—they usually thought attitudes had shifted more than they really had, or they even got the direction of change wrong. That’s like everybody’s darts landing six feet north of the target.

So whenever people make sweeping claims about how the present is different from the past, I wanna grab ‘em by the lapels and shake ‘em: “How do you know?? Did you, like, watch a season of Mad Men? Did you hear some random anecdote from your grandpa? Or is this coming from something you half-remember from your ninth grade social studies class? People spend years trying to figure these things out, but you can just kinda intuit it???"

I get so worked up about this because these claims actually matter. If you really think that people are less kind than they used to be, you are alleging a disaster. Moral decline would be very, very bad. Morality is the glue that holds our society together; if that glue disappears, our society falls apart. So if that’s happening, we should do something about it right away. But if it isn’t, instead of shouting “fire!” in a crowded theater, you should zip your lips so we can all watch Paddington 2 in peace2.

Dan and I set out to answer three questions. First, do most people think morality has declined, or is it just a vocal minority of curmudgeons? Second, could the curmudgeons be right? And third, if people are wrong and morality is not declining, why do people think it is?

FIRST, A NOTE TO THE PEDANTS

You might be thinking, “Morality—that’s a loaded term! People can use that word to mean lots of things. As Hegel said—”

Lemme stop you right there. You’re right, but fortunately none of the results I’m about to show you depend on using that particular word. You get the same thing if you ask about “kindness,” “honesty,” “respect,” etc. We call this “the illusion of moral decline” because it rolls off the tongue better than “the illusion of the decline of kindness, honesty, respect, and things like that.”

You can, of course, use words to mean anything you want. If you think same-sex marriage is immoral, you certainly think the US is far less moral than it was before 2015. Of course, lots of people (including me) would disagree with you. We can settle eternal questions of right and wrong later. For now, we only care about the parts of morality where pretty much everyone would agree.

Those consensual parts, by the way, are also what regular folks mean when they talk about moral decline. When pollsters ask people for examples of “moral decline,” the most frequent answers are things like “people don’t treat each other with respect” and “our government and business leaders lie to us”—things that we can all agree are bad.

Okay, goodbye, pedants! Onward to the science.

PART I: DO PEOPLE THINK MORALITY HAS DECLINED?

We started by scouring databases for every single survey we could find about people’s perception of moral change over time. We excluded any surveys that asked people only about specific groups (“Do you think the Wisconsin legislature is more ethical now than it used to be?”) or asked about moral issues where people might reasonably disagree on what’s good and what’s bad (“Do you think there are more swear words on TV than there used to be?”). We found 177 surveys with a combined sample size of 220,772 people.

On 84% of those surveys, a majority of respondents said that morality had declined. Here are a few examples:

We also found 58 surveys from 59 countries other than the United States, and they had a combined sample size of 354,120 people. Once again, on a majority of questions, a majority of people said that morality declined. The best data comes from two surveys that Pew did in 2002 and 2006. They asked people in every nation highlighted below whether moral decline is a problem in their country, and in every single country, a majority of people said that moral decline was a least a “moderately big” problem. So people all over the world really do seem to believe that morality is declining.

Two more interesting findings came out of all this data.

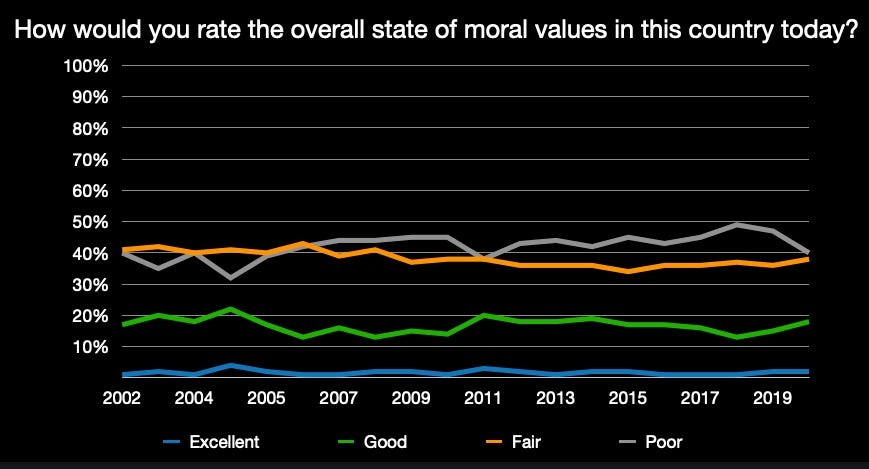

First, we don’t see any change in the proportion of people perceiving decline over time. That is, just as many people say that morality has declined today as they did a generation ago:

Second, when people are asked about longer periods of time (“How are things today compared to 50 years ago?”) they report more decline than they do when asked about shorter periods of time (“How are things today compared to last year?”). We have less data to work with here, because some questions don’t specify the time period at all (“In general, do you think morality has declined?”), but the trend is suggestive.

So it really seems like most humans believe that morality has declined. But look, all of these questions are a little weird. They ask about “morality” but don’t say what that means. They ask about the past without specifying when in the past. And sometimes the questions are very leading, like: “Do you think moral decline is the number one worst problem of all time, or not?”

If you really want to know whether people think that people are less kind, honest, nice, and good than they used to be, you have to ask them yourself. So that’s what we did next.

[KE$HA VOICE] IT’S GOING DOWN, I’M YELLING “MORAL DECLINE"

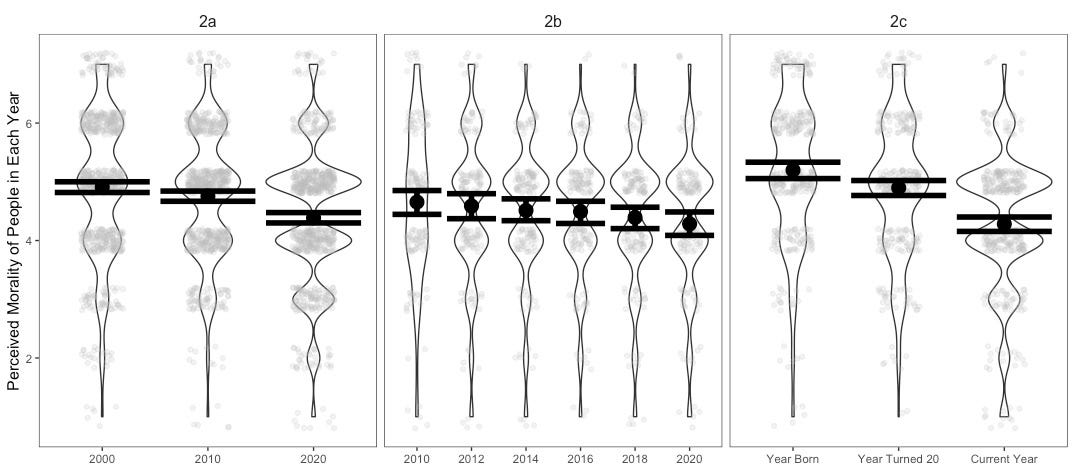

We got an online sample of US adults that was nationally representative in terms of age, race, and gender.3 We asked them to rate how “kind, honest, nice, and good” people were in 2020 (the current year at the time4), 2010, and 2000. People told us morality declined.

We got another sample and asked them about the years in between 2000 and 2020. People told us that not only has morality declined, it’s declining—you can even tell the difference even between 2016 and 2020.

Next, we got another sample and asked them to go further back in time: rate people today, then the year in which you were 20, and then the year in which you were born. People told us that morality has been declining for their whole lifetimes—things got worse from their birth year to age 20, and from age 20 to today.

Here are all those findings in a handy figure (higher numbers = more moral):

Once again, two interesting additional findings popped out of the data. First, you might think that “morality is declining!” is the kind of thing only an old person would say. But nope; young people say it too. When you ask people about moral decline over the course of their whole lives, older people say there’s been more. When you divide that amount by people’s age, however, you get the same number. That is, older and younger people agree on the rate of moral decline:

Second, you might think “morality is declining!” is a thing only conservatives say. Nope; liberals say it too. Conservatives perceived more decline than liberals, but even the strongest liberals agreed it was happening.

(No other demographic variables were strongly related to people’s perception of moral decline.)

So now it really really seems like people all over the world believe that people in general are less fundamentally good than they used to be. They think this decline has been going on their whole lives, and that it’s still going on today. And that belief cuts across every demographic group. We still don’t know, however, how people think this decline happened. That’s what we figured out next.

DUMMIES BEGONE

When people say “People aren’t as nice as they used to be!”, they could mean two things. They might mean “The same person is less nice today than they were in the past.” Let’s call that personal change. Or they might mean, “We lost some good people and gained some bad people.” Let’s call that interpersonal replacement.

These are tricky to think about, like trying to picture an Escher drawing in your head, so here’s an example I find helpful. Imagine you find out that students at a private school near you got way better SAT scores this year than they did last year. Two things might have happened. Maybe the school did something that made the same students way smarter (personal change). Or maybe they got different students to take the test: they kicked out all the dummies are recruited a bunch of smarty-pantses (interpersonal replacement). Both of those could make the SAT scores go up, but one is better teaching and the other is better cheating.

Similarly, personal change and interpersonal replacement could both lead to decline over time, but they do so in very different ways. Interpersonal replacement is a “kids these days” effect—the nice old people died and mean young people took their place. Personal change is an everyone effect—something is happening to individuals that makes them meaner (maybe Twitter, the news, fluoride in the water, etc.).

So when people say that morality is declining, are they talking about personal change, interpersonal replacement, or both?

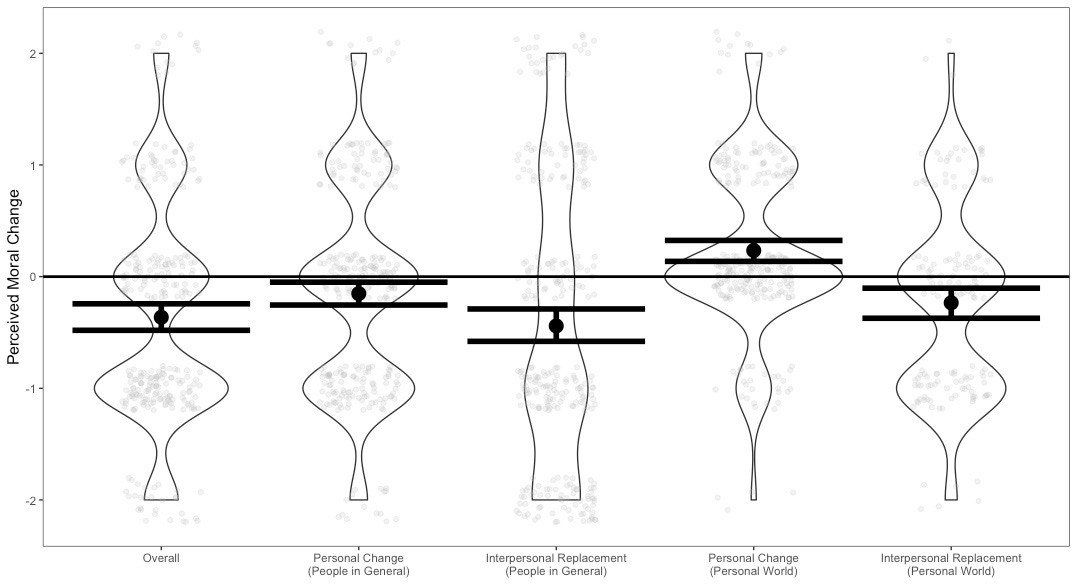

Both. We asked people about overall moral decline between 2005 and 2020, and then we asked them about personal change and interpersonal replacement between those years. People’s perceptions of personal change and interpersonal replacement predicted what they said about overall moral decline, suggesting that when people say “People aren’t as nice as they used to be!” they mean both that individuals have become nastier, and that some nice people have died off and mean people have replaced them.

That means the perception of moral decline isn’t just a “kids these days” thing. It’s a “people these days” thing.

PART II: HAS MORALITY ACTUALLY DECLINED?

Okay, so people think that people are less kind, honest, nice, and good than they used to be. Now we’d really like to know: are they right?

One big strike against this idea is that, for pretty much any awful thing you can think of—war, murder, slavery, child abuse, etc.—people seem to do less of it now than they used to. If morality has been in freefall for decades or even centuries, it’s a bit odd that people don’t squish each other’s skulls as much as they once did.

To be fair, though, when you ask people what they mean by “morality has declined,” they don’t mainly say things like “murder is up” or “people do terrorism.” Instead, they say things like, “People just don’t treat each other with respect anymore,” and “People used to make time for one another, and now they don’t.” Trying to measure everyday morality by homicide rates is sort of like trying to estimate the number of firecrackers by counting the number of nuclear warheads—maybe they go together, but maybe not. So has that kind of morality gone down, or what?

There’s no obvious and objective way to answer this question. It’s not like we have moral thermometers that have been taking measurement for decades, nor can we drill cores out of Arctic ice to determine ancient levels of morality. We have to make do with what we’ve got.

Fortunately, we’ve got a lot. For decades, survey companies have been asking people questions about their experiences with everyday morality, like, "Were you treated with respect all day yesterday?” and “Are people generally helpful, or are they looking out for themselves?” and “In the past month, have you helped a stranger who needed help?” If, as participants in Part I claimed, morality has been falling for decades, it should be pretty easy to find changes in people’s answers to these questions.

It turns out to be very hard to find changes in people’s answers to these questions. We found 107 surveys that were administered to over 4.4 million people between 1965 and 2020. We did some statistical tests to check whether there were any meaningful changes in people’s responses over time. We found none. Sometimes these moral indicators went up a little bit, sometimes they went down a little bit, but on average they went nowhere at all. For instance, here’s one from Gallup:

Note that every single year, in the same survey, about 70% of people say that morality is getting worse. So every year people give the same answer, and every year people say it’s worse than it was before.

Here’s another:

And another:

This goes on for another 104 surveys. We also searched for sources outside the US, and found 33 surveys with a combined sample size of over 7.3 million. These, too, showed no change over time.

Just because morality is not declining, of course, that doesn’t mean our current level of morality is good. There are still, in the Grammy-nominated words of the Black Eyed Peas, “People killin’, people dyin’, children hurt, hear them cryin’”. There just doesn’t seem to be more of that than there was before.

NEVER PLAY GAMES WITH ECONOMISTS

Here’s another way of answering the same question.

Social scientists have, for decades, brought people into the lab and asked them to play “economic games” like the Prisoner’s Dilemma and the Public Goods Game. (“Game” is a generous term for these; basically you make some decisions and get some money, or not. This is economists’ idea of fun.)

Last year, a team led by Mingliang Yuan tracked down as many of these studies as they could find, and then checked whether cooperation rates had changed over time. They expected to find that people are more likely to be selfish today. Instead, they found the opposite: cooperation rates increased about 10 percentage points from 1956 to 2017. Obviously, these games present people with pretty weird situations; they are not an objective peek into humans’ heart of hearts. But if you believe in moral decline, it’s hard to explain why people seem to be more willing to cooperate.

Maybe, though, people would get this one right. If you explained a Prisoner’s Dilemma to participants, told them that you know how cooperation rates have changed over time, and paid them a bonus for estimating the change in those rates correctly, do they nail it?

They do not nail it. When we did all those things, people estimated that cooperation had decreased by 10 percentage points. That is, they got the amount of change right, but the wrong direction. So even when money is on the line, even when we don’t use squishy terms like “morality,” and even when we can compare people’s perceptions directly to reality, we still find a sizable illusion of moral decline.

PART III: IF MORALITY HASN’T DECLINED, WHY DO PEOPLE THINK IT HAS?

In psychology, anything worth studying is probably caused by multiple things. There may be lots of reasons why people think morality is declining when it really isn’t.

Maybe people say that morality is declining because they think it makes them look good. But in Part I, we found that people are willing to say that some things have gotten better (less racism, for instance). And people still make the same claims when we pay them for accuracy.

Maybe because people are nice to you when you’re a kid, and then they’re less nice to you when you’re an adult, you end up thinking that people got less nice over time. But people say that morality has declined since they turned 20, and that it's declined in the past four years, and all that is true for old people, too.

Maybe everybody has just heard stories about how great the past is—like, they watch Leave It to Beaver and they go “wow, people used to be so nice back then.” But again, people think morality has declined even in the recent past. Also, who watches Leave It to Beaver?

We know from recent research that people denigrate the youth of today because they have positively biased memories of their own younger selves. That could explain why people blame moral decline on interpersonal replacement, but it doesn’t explain why people also blame it on personal change.

Any of these could be part of the illusion of moral decline. But they are, at best, incomplete.

We offer an additional explanation in the paper, which is that two well-known psychological phenomena can combine to produce an illusion of moral decline. One is biased exposure: people pay disproportionate attention to negative information, and media companies make money by giving it to us. The other is biased memory: the negativity of negative information fades faster than the positivity of positive information. (This is called the Fading Affect Bias; for more, see Underrated ideas in psychology).

Biased exposure means that things always look outrageous: murder and arson and fraud, oh my! Biased memory means the outrages of yesterday don’t seem so outrageous today. When things always look bad today but brighter yesterday, congratulations pal, you got yourself an illusion of moral decline.

We call this mechanism BEAM (Biased Exposure and Memory), and it fits with some of our more surprising results. BEAM predicts that both older and younger people should perceive moral decline, and they do. It predicts that people should perceive more decline over longer intervals, and they do. Both biased attention and biased memory have been observed cross-culturally, so it also makes sense that you would find the perception of moral decline all over the world.

But the real benefit of BEAM is that it can predict cases where people would perceive less decline, no decline, or even improvement. If you reverse biased exposure—that is, if people mainly hear about good things that other people are doing—you might get an illusion of moral improvement. We figured this could happen in people’s personal worlds: most people probably like most of the people they interact with on a daily basis, so they may mistakenly think those people have actually become kinder over time.

They do. In another study, we asked people to answer those same questions about interpersonal replacement and personal change that we asked in a previous study, first about people in general, and then about people that they interact with on a daily basis. When we asked participants about people in general, they said (a) people overall are less moral than they were in 2005, (b) the same people are less moral today than in 2005 (personal change) and (c) young people today are less moral than older people were in 2005 (interpersonal replacement). Just as they did before, participants told us that morality declined overall, and that both personal change and interpersonal replacement were to blame.

But we saw something new when we asked participants about people they know personally. First, they said individuals they’ve known for the past 15 years are more moral today. They said the young folks they know today aren’t as moral as the old folks they knew 15 years ago, but this difference was smaller than it was for people in general. So when you ask people about a group where they probably don’t have biased exposure—or at least not biased negative exposure—they report less moral decline, or even moral improvement.

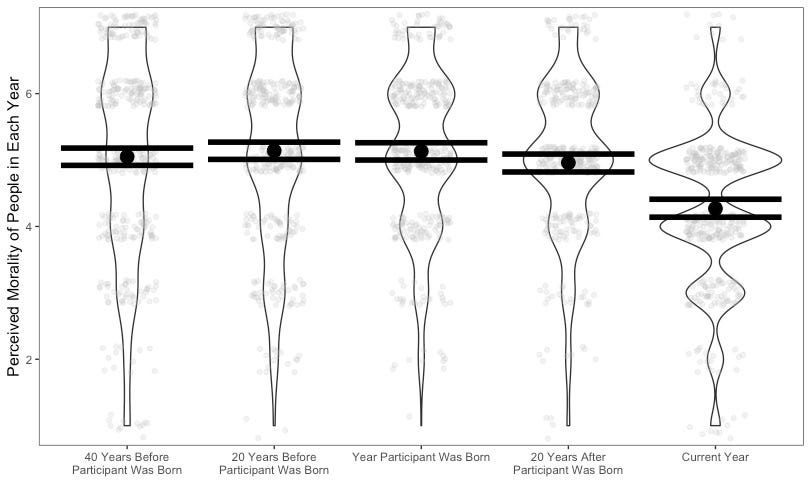

The second thing that BEAM predicts is that if you turn off biased memory, the illusion of moral decline might go away. We figured this could happen if you asked people about times before they were born—you can’t have memories if you weren’t alive. We reran one of our previous studies, simply asking participants to rate people in general today, the year in which they turned 20, the year in which they were born, 20 years before that, and 40 years before that.

People said, basically, “moral decline began when I arrived on Earth”:

Neither of these studies mean that BEAM is definitely the culprit behind the illusion of moral decline, nor that it’s the only culprit. But BEAM can explain some weird phenomena that other accounts can’t, and it can predict some data that other accounts wouldn’t, so it seems worth keeping around for now.

CONCLUSION: FIGHTING THE INVISIBLE FIRE

Let’s check back on our three questions.

Do people in general think morality has declined? Yes.

Are they right about that? Probably not.

So why do they think it? Could be lots of reasons, and biased memory plus biased exposure might be one of them.

That’s where the paper ends, but here’s what I’ll add in my own words.

It’s very easy to feel like you know something about the past without actually knowing anything about the past. I just showed you data from more than 500,000 people who were asked whether morality has declined, and virtually none of them said “Gosh, I don’t know.” But for them, that was the right answer. They don't know. It took us years and another 12 million people to come up with even a halfway decent answer, which is “probably not.” And yet an answer came to everyone’s minds effortlessly, and they were happy to share it, and even to back it up when we asked them more about it. The past is a foreign country, but we all have the vivid delusion that we’ve lived there for a long time and know everything about it.

And look, it’s fine to have strong opinions about things that you know nothing about—that’s kind of what the internet is for. But it’s not fine when those strong opinions lead to demands for actual changes in the world. If you think that morality is declining, then you must think that some switch has been flipped in society, causing it to produce worse humans. No doubt you would want to un-flip that switch, whatever you think it is: smash the social media companies! Kill all the politicians! Ban the bad books! None of that is going to reverse the trend, because the trend doesn’t exist. It’s like activating the sprinkler system in a building that’s not on fire.

(This is exactly what aspiring despots do, by the way: they cry catastrophe as a way of justifying their extreme measures. “Things are going to hell, but make me king and I’ll fix it all.”)

We’ve focused here on morality because that’s an area where we think this illusion is both strong and important. But there may be many others, because lots of people are saying that lots of things are declining: democracy, culture, reason, art, our children, the future. I’m not saying all of these are illusions, but they sure sound familiar.

Notice that, while lots of people are happy to tell you about Golden Ages, nobody ever seems to think one is happening right now. Maybe that’s because the only place a Golden Age can ever happen is in our memory.

Or the early 1990s, when I was born. Man, people were so nice back then!

I know it’s odd for me, Mr. Rise and Fall of Peer Review, to be publishing in a peer reviewed journal. We submitted this paper last July, and my experience getting this paper published is part of the reason I wrote that post.

Paddington 2 was, at least for a time, the best-reviewed movie of all time. Citizen Kane should have had more CGI bears.

Internet data is sketchy unless you’re careful. I explain all the things we do to ensure data quality here.

You might thinking, “2020—that’s a weird year! Could this be a pandemic effect, where people think that covid brought out the worst in all of us?”

It’s a reasonable question, and the answer is no. First, we happened to run one of these studies in January 2020, when covid was barely a news story in the US, and the results look identical to the results we got after covid was everywhere. We ran more studies in 2021 and 2022 and got the same results again. Plus, all the preexisting survey data we collected predates the pandemic, and those folks think morality has declined, too.

This is all so fabulous and immensely reassuring, and I'm going to sip it like a fine wine for the rest of the day.

Thank you for being so rigorously interested in this question that you put such an immense amount of work into concluding "we're not sure, but if one thing looks likely, it's that all this absolute certainty sure looks dead wrong". The best and wisest of answers.

Congratulations, Adam (and Dan). Amazing work.

Is it possible Adam that the persistence of perceiving ‘moral decline’ is actually caused by accelerated shifts in the definition of morality itself? Morality is only an interpretive symbol system. It is overlaid linguistically onto behavior patterns .The extent of your research is impressive but most of the survey items you list are not really measures of ‘behavior’ such as: when I have a gift most recently it was reciprocated within 12 months. No one writes surveys like this in part because we doubt anyone could answer them accurately. A lot of moral behavior is not capturable except through direct observation and mass ethnography (something no one has figured out and only the Feds have the resources to execute.