An invitation to a secret society

Or: why you should be a lizard

I hereby invite every curious human to do science and post it on the internet.

Ask questions, collect data, write stuff, and make it available to everyone. You should feel as free to do and share research as you would feel uploading a video to YouTube or a song to Spotify.

You don’t actually need my or anyone else’s permission to do this, but sometimes people need a little encouragement, so: come on in!

Actually, let me make that a little more urgent: Please come in, we need you.

See, scientific progress has slowed. We fund more research than ever and get way less bang for our buck. We spend 15,000 years of collective effort every year on a peer review system that doesn’t do its job. Fraudsters can publish dozens of papers before they get caught, if they get caught at all.

This is bad. Our world is full of problems, and science is the main way we solve them. We’ve got climate change, an obesity epidemic, and a lot of sad people. There are folks dying of poverty and preventable disease. Heck, we still mainly make electricity by burning dinosaur bones. This can’t be as good as it gets.

Lots of people have lots of ideas about how to get science started again. Give out badges for good behavior! Do giant replication studies! Demand tinier p-values!

I don’t think any of these solutions will work because they’re trying to solve the wrong problem. They’re aimed at stamping out the worst research, but science is a strong link problem: we make progress by producing good stuff, not by preventing bad stuff. When you’re in a strong-link problem, the answer is to turn up the weirdness. More wild hypotheses! More risky research! The useless ideas will die from disuse, but the useful ideas will live on.

This is where you come in.

LET’S ALL BE MAMMALS AND DIE

Professional science does a lot of good stuff. It gives people paychecks, health insurance, research funding, offices, and colleagues. It allows large groups to work together on big projects like launching telescopes into space. And it gives young, curious people a place to start: if you want to ask and answer questions about the universe, academia is an obvious career path.

But that good stuff comes at a price. Professions are bundles of weak-link interventions; they keep out quacks, but they also keep out revolutionaries. They enforce standards, which tends to make things…standard. They select for a pretty homogenous group of people—in this case, folks who got good grades in college, did research in the right institutions with the right people and published in the right journals. Then they make all those people even more similar to one another, steeping them in the same culture and putting them in competition for the same rewards, like grants, jobs, and citations.

Right now, professional science is like a world where every organism is trying to be a mammal. Mammals are great: milk-producing glands, body hair, ears that have three bones in them, what’s not to like? But if you’ve only got mammals, you’re in big trouble. Monocultures are fragile and prone to collapse because every single organism has identical weaknesses. What you need is an ecosystem—hawks, sea urchins, fungi, various types of fern, and so on.

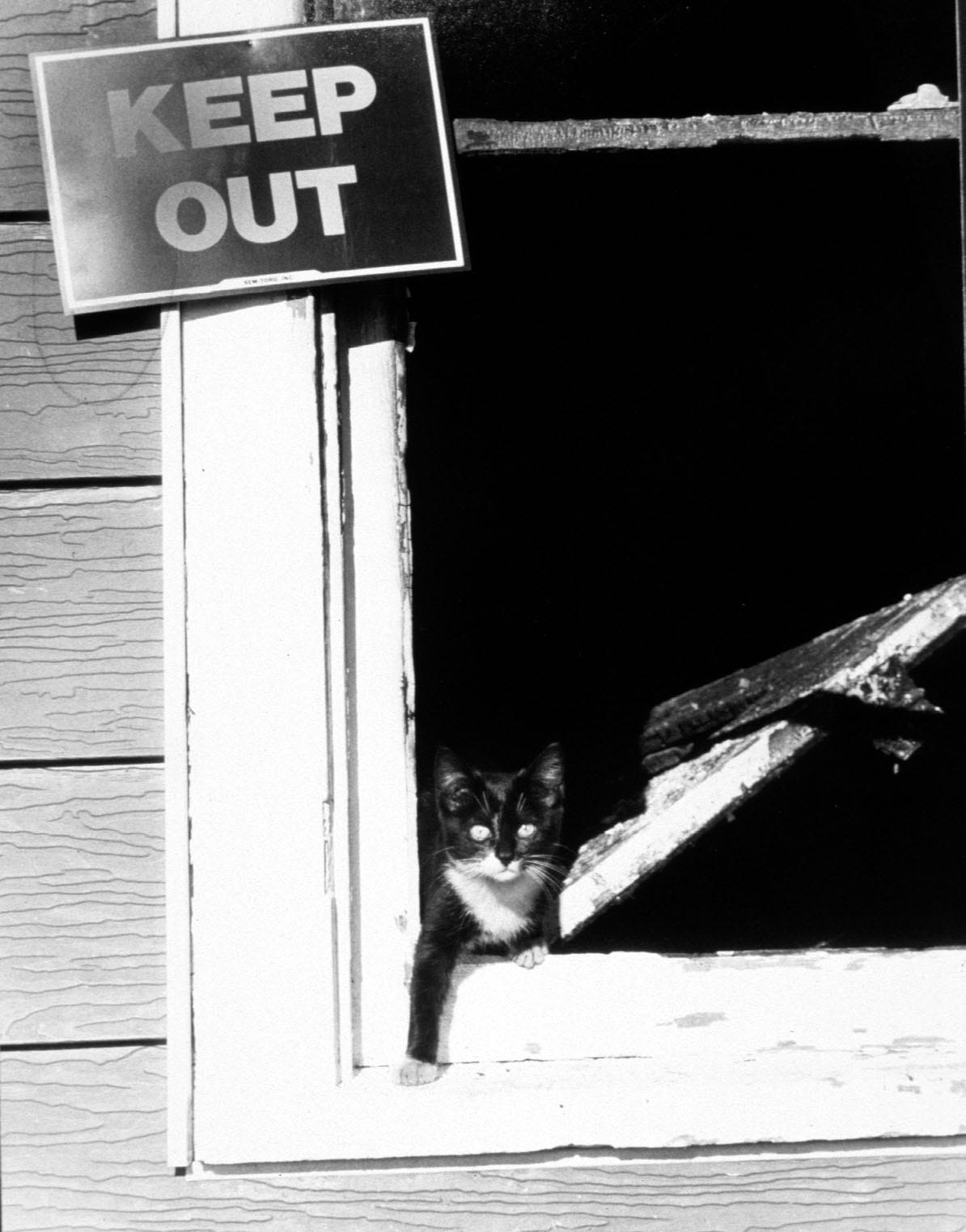

Creating diverse ecosystems is hard for humans because they like to do whatever everyone else is doing, even when they know it’s wrong. So when you’re trying to be a mammal and you see someone else trying to be a lizard, you might think they’re just doing a bad job being a mammal. “You should try having little hairs all over your body,” you might tell them. But a lizard isn’t a bad mammal. It’s a lizard. Its job is to eat flies and bask on rocks.

What I’m saying is: be the lizard. The mammals—that is, mainstream scientists, the ones who get PhDs and professor jobs—have their niche covered. What we need is more people doing botany in their backyards. We need basement chemists. We need amateur geologists and meteorologists.

Heck, if some mammals want to try a different niche, so much the better: ditch the projects you think are pointless, do the thing you think is most important, write it in your own words, and put it on the internet. There’s plenty of space for everyone.

“HELP, I AM WORRIED THAT MOST OF THE STUFF THESE PEOPLE MAKE WILL BE BAD!”

It will be! But remember two things.

Most of the professional science we produce right now is bad. Seriously, pick a paper at random and see how well it holds up. We recently found out that the chair of a Harvard department probably faked a bunch of her data. The bar is not high, folks!

Bad stuff is okay. I cannot stress enough that science is a strong-link problem, and what we really care about is how much good stuff we get, even if it means we also get a bunch of bad stuff.

THE DEATH OF THE DABBLERS

What I’m proposing here isn’t actually new. In fact, it’s ancient. People have been making knowledge in all sorts of ways ever since Socrates started walking around and saying stuff.

Some of these people didn’t have traditional jobs because they didn’t have to. Francis Galton, the guy who came up with (among many other things), correlation, twin studies, fingerprinting, weather maps, and questionnaires, was independently wealthy. So were Darwin and Boyle and many of the members of the original Royal Society and British Association. As I wrote in my review of Galton’s autobiography, dabbling in science used to be a common pastime for rich dudes—a little astronomy here, a little vivisection there.

Money makes everything easier, obviously, but plenty of now-legendary scientists had to do their thing part-time while finding other ways to pay the bills. Einstein published some of his most important work while he was still a patent clerk. Thomas Bayes, whose theory of probability still sets nerd hearts aflutter, was a priest. Gregor Mendel, the pea plant guy who founded genetics, was a monk. Galileo and Da Vinci spent much of their careers trying to worm their way into the good graces of various patrons. Marie Curie did her early work in a shed next to a French university; they only gave her a job after she got famous. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek sold drapes to support his side hustle of inventing microbiology.

I predict that these last few decades, in which professional science nearly eradicated the dabbler and the part-timer, will turn out to be a blip in history, for two reasons. First, the structures of academia are so warped, competition is so fierce, and opportunities are so scarce that even its biggest adherents spend most of their time complaining about it. When numerous Nobel Laureates are saying that they couldn’t have done their Nobel Prize-winning work in today’s system, something’s bound to break.

And second, for the first time in human history, the tools of science are cheap, and knowledge is nearly free. Your laptop can store and analyze more data than Galileo could have even imagined. Internet pirates have toppled the scientific paywall and made nearly every paper ever written freely accessible to everybody. Nobody can stop you from uploading a PDF of your research to the internet, where tens of thousands of people might see it. The only thing stopping you from jumping in is your own fear.

MY PROMISE TO THE LIZARDS

If you're interested in accepting this invitation, here are four ways I can help.

#1: If you email me for help on a scientific project, I will respond.

I might not respond right away—I’m pretty slow at email—but I will get back to you eventually. I will take your ideas seriously and talk to you like a colleague, because we are all colleagues in the great project of understanding the universe. That also means if your ideas seem crazy or your methods seem flawed, I’ll tell you. I can't keep up every email chain indefinitely, but I’ll reply to everyone at least once, or until I simply can’t keep up.

Of course, there are lots of subjects that I know nothing about, which brings me to:

#2: I’ll connect you to other people who have similar interests.

I set up a Discord server for folks doing science, and I’ll add anyone who reaches out and explains what they’re looking to do. Once we reach a critical mass, this could be a place where people go for advice, to discuss ideas, and find collaborators.

I'll check in occasionally, but I expect to be pretty hands-off. I’m intending this to be a place where people talk to each other, not to me.

#3: If I see you doing good stuff, I'll link to it.

Self-explanatory. And finally:

#4: I'll answer a few questions to get you started.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT DISCOVERING FUNDAMENTAL TRUTHS ABOUT THE UNIVERSE

Where do I start?

Probably with something that seems weird to you. Something that annoys you because you don't understand it. Some parts of research can be boring; wanting to know the answer really bad will help keep you going.

Also, read The Scientific Virtues.

What if I don’t have any formal training or credentials?

Formal scientific training is way less formal than you think.

You might imagine that when you enter a PhD program, a wise old scientist sits you down and tells you all the secrets of science. This doesn't happen. You take a few classes, most of them totally irrelevant to the research you end up doing. When you have a question about statistics, you go to StackOverflow. Most of the papers you read are the ones you find for yourself, probably using Sci-Hub because it's easier and faster than accessing papers legally through your university.

I was lucky enough to have a terrific advisor who taught me a ton, but that's pretty rare—plenty of people spend years of their PhD just waiting for their boss to respond to an email. So if your scientific education is mostly DIY, well, so is everyone’s.

Haven’t all the easy ideas been taken?

No, and if you say that again I will fight you. If you start with something you don’t understand, there’s a good chance that soon enough you’ll bump up against something that no one understands.

How can I do anything useful when I don’t have any resources?

You can do a lot of interesting stuff with cheap, simple methods. Pop culture has become an oligopoly was just "copy data off the internet and make some graphs." Do conversations end when people want them to? was just "have people talk and then ask them when they wanted to stop." Slime Mold Time Mold's Potato Trial and Half-Tato Trial were just "get people on the internet to eat potatoes and weigh themselves." Rita Levi-Montalcini discovered how the nervous system develops by poking chicken eggs with a needle in her bedroom/laboratory.

In fact, if you're willing to use simple methods, you actually have an advantage over professional scientists. The pros wanna look cool to their colleagues (and win big grant money from the government), so they have to use the fanciest, most advanced techniques, even when simpler stuff would do them better. That's great for you, because it means the professionals will rarely investigate important questions if they don't require giant magnets or ten thousand computer cores or whatever. Cheap ideas are just lying around for you to scoop up. So scoop ‘em, darn it!

What if I do a bad job?

If you work on a project that goes nowhere, who cares? Move on to the next one. Don't worry about making mistakes—there is a 100% chance you will make a mistake, so when it happens, go "oops" and fix it. Be honest and transparent. The stakes are way lower than they seem.

What if no one listens to me?

That might happen! It's happened to lots of people who turned out to be right, like the guy who told doctors they should wash their hands, and the guy who hypothesized that all the Earth's landmasses used to be one big Pangea.

In my experience, though, the internet is smaller than you imagine, and good work tends to travel. But you should do this because you think it's important and you like doing it. If you're doing it because you want influence and affirmation, reconsider!

What if people yell at me?

They might. Whenever you post something publicly, there's a chance people will be mean to you, because some people think that being nasty makes them look smart. Unfortunately, the only solution is to ignore them.

Is it legal to do science on your own?

Don't laugh—I've had professional scientists ask me this!

In short: yes. You don't need a license to do science. But you still have to obey the law. You can't pretend to be a doctor, steal people's data, secretly lace someone's lunch with chemicals and watch their reaction, etc. You shouldn’t do anything illegal or immoral in pursuit of scientific truth, just like you shouldn’t do it in pursuit of anything else.

How do I know whether someone has tested my idea already?

Career scientists don’t get any credit for re-dos, so they worry a lot about making sure no one has scooped them. But it’s actually good for science if people are replicating previous work, so long as the idea was a useful one in the first place. Many studies are bad, some of them are straight-up fraudulent, and it’s pretty likely that you’ll ask the question in a different way than your predecessors did. Plus, replicating previous work is good practice. So if you really want to get to the bottom of something, just go for it.

What can I do that a professional scientist can’t?

Oh man, tons. Here are just a few things.

Screw around on projects that might be a total waste of time, just for fun.

Write a paper that’s like “Hey here’s a weird thing I found and I have no idea why it happens”

Research stuff that’s bizarre or unpopular or disconnected from any existing literature.

Write a paper that’s like “Hey my hypothesis was totally wrong, what’s up with that”

Work on super long-term projects that only bear fruit after decades of work

Do you have any helpful examples of people doing science outside of professional institutions?

Yes!

Aella is a sex worker and a scientist. She runs big surveys about people’s sexual behaviors and tries to learn from them.

Experimental Fat Loss is a pseudonymous blogger who has run lots of self-experiments on weight loss.

Julian Gough is unspooling a theory of the universe on his Substack, which involves making detailed predictions for what the International Pulsar Timing Array will detect.

Slime Mold Time Mold are mad scientists who are, among other things, trying to solve the obesity epidemic. They also have a terrific series on how to run one-person or few-person studies, which could be a good place to start.

This sounds cool, but I don’t know if I really want to do science. Are there other ways I could help?

Science needs programmers, project managers, grant writers, editors, research assistants, funders, and a million other things besides. If you want to be involved, get aboard! The Discord will be a good place to start.

HOW TO GET KARATE CHOPPED BY ME

If you call what I’m describing here “citizen science,” I will karate chop you. I despise that phrase. All science is science, regardless of the author’s credentials. Slapping the label “citizen” on science done by people working outside of institutions is just a way of widening the moat around the ivory tower, of reinforcing the false idea that only people with PhDs and academic jobs get to do “real” science.

You can have impeccable academic credentials, land a fancy job at an elite university, and publish hundreds of papers, all without ever putting a useful piece of knowledge into the world. Many people pull this off! Sometimes they do it by writing papers that are true but meaningless. Other times they do it by opening up an Excel spreadsheet and typing in some fake data. These people are not scientists, no matter what it says on their office doors.

So I don’t care if you’re a nobody from nowhere. I don’t care if you pay your bills by cleaning toilets, selling Beanie Babies on eBay, or managing an Olive Garden. If you discover some useful nugget of truth about the universe, you’re a scientist.

THE BEAUTIFUL WAY

One more thing: I believe that anything that people make on their own, anything they create for pure pleasure, is beautiful.

People will sit alone in their basements playing guitar simply because they like the sound. They’ll paint, write poems, and whittle wood into little figurines without any expectation of gaining money or fame. It just makes 'em feel good. All of that is beautiful.

Anything that humans only produce in exchange for money, on the other hand, is ugly. No one designs billboards or writes instruction manuals for microwaves on a lark. When people pick up a guitar of their own accord, they sing about love and longing, not about how Tide laundry detergent cleans even the toughest stains. That doesn’t mean these endeavors are bad—someone’s gotta tell you how to work your microwave—but it means they aren’t beautiful.

Right now, almost no one sits down and writes a scientific paper for pure pleasure. I talk to people all the time who signed up for academia thinking they were going to uncover the mysteries of the universe, and they ended up doing something that kind of looks like that, but isn't really, and somehow feels pretty bad a lot of the time. They say things like, "I usually come to hate my papers by the time I get them published."

That doesn't mean that science is inherently ugly. It means we aren't doing it the beautiful way. When you do science under duress, you produce something that looks a lot more like a Tide commercial than a love song. It's still possible to make something useful that way, but it's very hard to make something beautiful.

You, though, can do things the beautiful way. You can make knowledge the same way you would make music in your basement: just because you like doing it. I hope you will. I'll be waiting to hear from you.

We need a universal basic income which would allow people to be creative, follow their interests, experiment and take risks without ruining their lives.

“The fact is that the work which improves the condition of mankind, the work which extends knowledge and increases power and enriches literature, and elevates thought, is not done to secure a living. It is not the work of slaves, driven to their task either by the lash of a master or by animal necessities. It is the work of men who perform it for their own sake, and not that they may get more to eat or drink, or wear, or display. In a state of society where want is abolished, work of this sort could be enormously increased.”

― Henry George, Progress and Poverty (1879)