Declining trust in Zeus is a technology

OR: leaving the land of tiny muffins

Randomized-controlled trials only caught on about 80 years ago, and whenever I think about that, I have to sit down and catch my breath for a while. The thing everybody agrees is the “gold standard” of evidence, the thing the FDA requires before it will legally allow you to sell a drug—that thing is younger than my grandparents.

There are a few records of things that kind of look like randomized-controlled trials throughout history, but people didn’t really appreciate the importance of RCTs until 1948, when the British Medical Research Council published a trial on streptomycin for tuberculosis. Humans have possessed the methods of randomization for thousands of years—dice, coins, the casting of lots—and we’ve been trying to cure diseases for as long as we’ve been human. Why did it take us so long to put them together?

I think the answer is: first, we had to stop trusting Zeus.

To us, coin flips are random (“Heads: I go first. Tails: you go first.”)1. But to an ancient human, coin flips aren’t random at all—they reveal the will of the gods (“Heads: Zeus wants me to go first. Tails: Zeus wants you to go first”)2. In the Bible, for instance, people are always casting lots to figure out what God wants them to do: which goat to kill, who should get each tract of land, when to start a genocide, etc.

This is, of course, a big problem for running RCTs. If you think that the outcome of a coin flip is meaningful rather than meaningless, you can’t use it to produce two equivalent groups, and you can’t study the impact of doing something to one group and not the other. You can only run a ZCT—a Zeus controlled trial.

HERE COME THE PITCHFORKS

It’s easy to see how technology can lead to scientific discoveries. Make microscope -> discover mitochondria.

Clearly, though, sometimes those technologies get invented entirely inside our heads. Stop trusting Zeus -> develop RCTs.3

Which raises the question: what mental technologies haven’t we invented yet? What brain switches are just waiting to be flipped?

Well, maybe one of them looks like this:

And this:

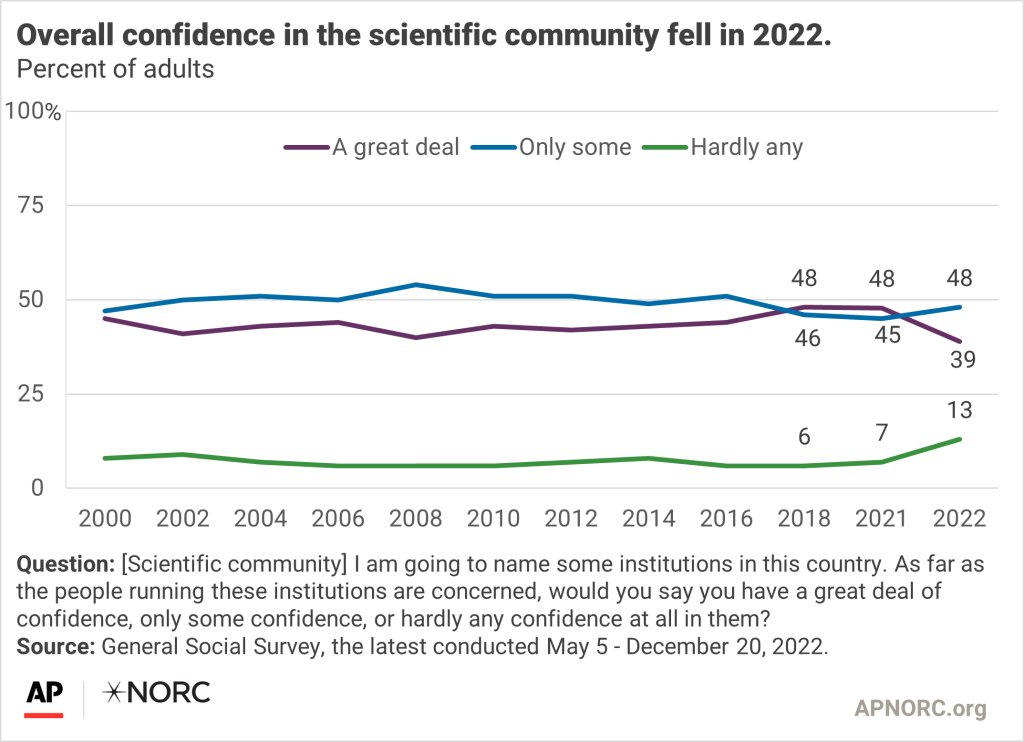

This might just be a blip—as Dan Gardner points out, declines in institutional trust tend to be smaller, and more limited to the US, than people think. But it’s at least a hint that people are starting to say, “Hey, kinda seems like the experts aren’t doing a great job.”

This worries a lot of people, especially the experts themselves, who view this trend with all the pleasure of a hated king watching his peasants sharpen their pitchforks.

I, on the other hand, see a big opportunity here.

I'M SORRY A TIGER ATE YOU BUT THERE WAS NO WAY TO PREVENT IT

For centuries, the smartest people on earth had one aspiration: produce some minor improvements on ancient scholars like Aristotle and Galen. Accordingly, that’s all they ever did. To invent a new world, humans first had to stop being so impressed with the old world. That was the original piece of mental technology that set off the Scientific Revolution and everything that came after it—the belief that we can do better.

At some point, we mothballed that belief. Now, the prevailing wisdom is that ideas are getting harder to find. Every generation should expect to discover less than the previous generation did; scientific progress should asymptote to zero. Yes, we dethroned Aristotle and Galen, but this was a one-time event that can never be repeated. If you missed it, too bad! We are stuck, once again, making tiny improvements to the ideas of our forefathers, which shall reign for all eternity.

I am continually gobsmacked that this pernicious idea wanders around our culture virtually unopposed. It’s like a tiger escaped from the zoo and is running around the city gulping down civilians, and everyone’s like, “Well of course tiger attacks are inevitable, nothing can be done about that.” What a diabolically clever self-fulfilling prophecy: if people believe that a radically better world is impossible, they'll never try to create it, and they’ll prove themselves right.

That’s why I’m so excited for people to become less impressed with our modern day Aristotles and Galens. Perhaps then people will be inspired to outdo them. The last time people started feeling this way, we got, uh, pretty much everything that was discovered from 1543 onward. So I’m kinda looking forward to seeing what happens this time around.

THE LAND OF TINY MUFFINS

I hope that inspiration comes soon, because right now we are sorely lacking in it. Today, the primary function of our scientific and educational institutions is to take in young people and lower their ambitions. “Oh, you want to change the world? You should join our Young World-Changers Program, where we do leadership seminars and write on whiteboards and discuss how nice it would be to change the world, if only such a thing were possible.”

I lived in this world for a long time, a world full of people eating tiny muffins from breakfast buffets and listening to talks, all the while going, “We’re doing it, we’re doing it!” Success meant getting invited to the cooler conferences, where the muffins are tastier and the speakers are more famous.

If I worked really hard, I knew, I could one day graduate from muffin-eater to talk-giver. I wanted that really bad. Being at the front of the room, behind the podium, a Thought Leader, a real life galaxy brain—that seemed pretty cool, which justified any steps it took to get there, no matter how onerous or debasing.

Then, couple years ago, I looked around and realized that I didn’t actually admire most of the people I was trying to be. I envied what they had and I feared what they could do to me, and I mistook those feelings for admiration; I thought I was looking up to them when I was only looking up at them. Many of them were petty and cruel, uncurious about ideas except as a means for acquiring status, quick to decry injustice but unwilling to risk anything to rectify it, usually polite but rarely honorable, busy but useless, eminent but uninspiring, well-spoken but cowardly. I knew I would only become more like these people if I kept going, so I stopped.4

This was true both inside science and in the Achievementsphere more generally, where people with highfalutin resumes kept turning out to have lowfalutin character. I know this seems naive now, but I guess I assumed that respected people would be respectable. Otherwise, how did they get where they got? I hadn’t yet heard about Goodhart’s Law, hadn’t yet realized how every system is vulnerable to the slithering schemes of sociopaths, hadn’t yet seen how institutions can’t tell the difference between looking good and being good.

(One moment that really drove this home for me was when I was talking to some friends and we realized we had all had creepy, off-putting interactions with the Dean of Inclusion.)

I know academics are always dramatic about our world, as if we’re the only ones with jobs that have downsides. (“Did you know that, in industry jobs, you make one billion dollars every week and each morning your boss kisses you on the forehead and says what a good boy you are?”) This same story plays out everywhere, of course. Every profession and organization has its own hierarchy that rewards the villainous and the virtuous alike, and that makes everyone worse off for participating. It’s like playing a life-sized game of Monopoly, where you can get so caught up in learning the rules, following all the ups and downs, and trying to win that you can forget the money is fake and cannot be traded for goods or services, and that the person who wins is usually the one who snuck a few $500s from the bank when no one was looking. Plus, you’re competing to see who can be the biggest landlord. It’s a stupid game with a stupid prize, but it’s hard to walk away—you’d lose all your Monopoly money!

I don’t literally believe these fake systems of achievement were set up by powerful people who wanted to make sure that any potential boat-rockers never rock the boat too much, but they do work suspiciously well. It’s kind of like when your toddler wants to help you in the kitchen and you distract them with a plastic kitchen playset instead so that they can pretend to cook without hurting themselves. But if someone did create a bunch of fake social games as a way of co-opting people’s ambition and keeping themselves atop the hierarchy, I gotta say: they nailed it.

The only way to get out of Tiny Muffin World is to realize how dumb it is. That’s why I’m optimistic about people putting less blind faith in science and academia, especially because those are supposed to be institutions founded on not putting blind faith in things.

ZEUS TAKE THE WHEEL

A few months ago, I gave a talk at a university that I’ll leave unnamed. At the end, a PhD student asked, “But if we don’t publish in journals, how will we get people to trust us?”

I answered, “By doing good work and making it transparent and accessible.” But man, what a question! If you’re like, “How do I get my friends to trust that I’m a good person?” the answer is be a good person. There’s no trick to it.

Here’s an example. Lots of people are skeptical of the medical establishment and prefer not to interact with doctors. But very, very few of those skeptics would refuse to go the hospital if they, say, fell down the stairs and snapped their leg in two. That’s because emergency departments are so undeniably good at fixing busted legs that you'd be crazy to prefer poultices and witch-doctoring instead. This is what victory looks like: a case where the experts have vanquished the cranks so thoroughly that everyone can see it.

Those successes should be way more common. Anybody who is tethered to reality by believing in empirical evidence, experimentation, testing theories, all that science stuff—they have a gigantic advantage over the people who form their worldviews by looking at goat entrails or consulting the stars or whatever. It shouldn’t even be close. If patients can’t tell the difference between you and the goat entrail people, you better tug harder on your tether and pull yourself closer to reality, because you’re embarrassing yourself. It’s like spending years practicing your Super Smash Bros. technique and then losing to a 10-year-old who just mashes the buttons.

That’s why I’m not sympathetic to the most common worry about declining trust: if the public stops trusting mainstream experts and abandoning traditional institutions, they’ll start trusting sweaty podcasts charlatans and joining terrorist cells instead. I, too, would like to beat the charlatans and the terrorists, which is why I want to do better than, “Don’t trust those guys—they lack the proper accreditation!” If that’s all you got, people shouldn’t trust you. Instead of arguing from expertise, you should use your expertise to make better arguments.

I know this will make some people very worried. They think that deferring less to experts means nuking our whole epistemological edifice and succumbing to the “post-truth” world. It’s playing dice with our future!

Well, I have no fear. I know Zeus will make those dice come up just the way they should.

Although recent evidence suggests they are slightly less than random: about 51% of the time, coins come up on the same side that was up when they were flipped.

Of course, whenever we say that people in the past believed something, we can only mean the people we know about, who were probably weird for their time because they could write about themselves, or had someone else to write about them. There may have been lots of ancient folks who thought that casting lots to figure out the will of the divine was a silly thing to do. Just like how most people today believe that the world is round, with a few obvious exceptions.

This was just the first of many steps, of course—it’s not like 1948 was the year people started doubting that God interferes in coin flips.

I was confused in part because I had such good mentors early on and so I assumed good mentors were common. It was like I bought two winning lottery tickets back-to-back and I was like, “Why people don’t invest more in lottery tickets? They’re great!”

"Instead of arguing from expertise, you should use your expertise to make better arguments." I will be quoting this (and will try not to be obnoxious when doing so). Thanks Adam!

I have nothing substantive to say other than that I continue to be flabbergasted by how good you are as a writer -- you keep writing these pieces that compel me to share them with friends who don't even care one whit about the scientific establishment (I'm in industry), and they end up reliably amazed and entertained.

I think I was also compelled to comment because a ~decade ago I found myself at a fork in life reminiscent of your description that starts with "Then, couple years ago, I looked around and realized that I didn’t actually admire most of the people I was trying to be. ...", and ended up leaving for industry instead of continuing on to academia. In my case, I was doing a physics degree in my boyhood quest to become a theorist of some sort. (I think it also helped for my decision that I wasn't good enough to get into R1 grad programs.) I think earning well and working on not-too-uninteresting data analytics problems have helped, but I've always wistfully wondered about what could've been; your essays have helped me un-tint that rose-tinted counterfactual.