Do conversations end when people want them to?

N = 1172

Years ago, I was getting ready for a party and I suddenly realized something: I didn’t want to go to the party. Inevitably, I knew, I was going to get stuck talking to someone, and there wouldn’t be any way to end the conversation without embarrassing both of us (“It’s been great talking to you, but not great enough that I want to continue!”).

But then I thought, wait, what makes me think I’m so special? What if the other person feels exactly the same way? What if we’re all trapped in this conspiracy of politeness—we all want to go, but we’re not allowed to say it?

Surprisingly, no one knows the answers to these questions. Eight billion humans spend all day yapping with each other, and we have no idea if those conversations end when people wish they would. So my PhD advisor Dan and I set out to get some answers using the most powerful methods available to us in psychology: we started bothering people.

(This is the blog version of a paper I published a few years ago; you can read the whole paper and access all the materials, data, and code here.)

STUDY 1

~~~METHOD~~~

We surveyed 806 people online about the last conversation they had: how long was it? Was there any point when you were ready for it to be over? If so, when was that?1

~~~RESULTS~~~

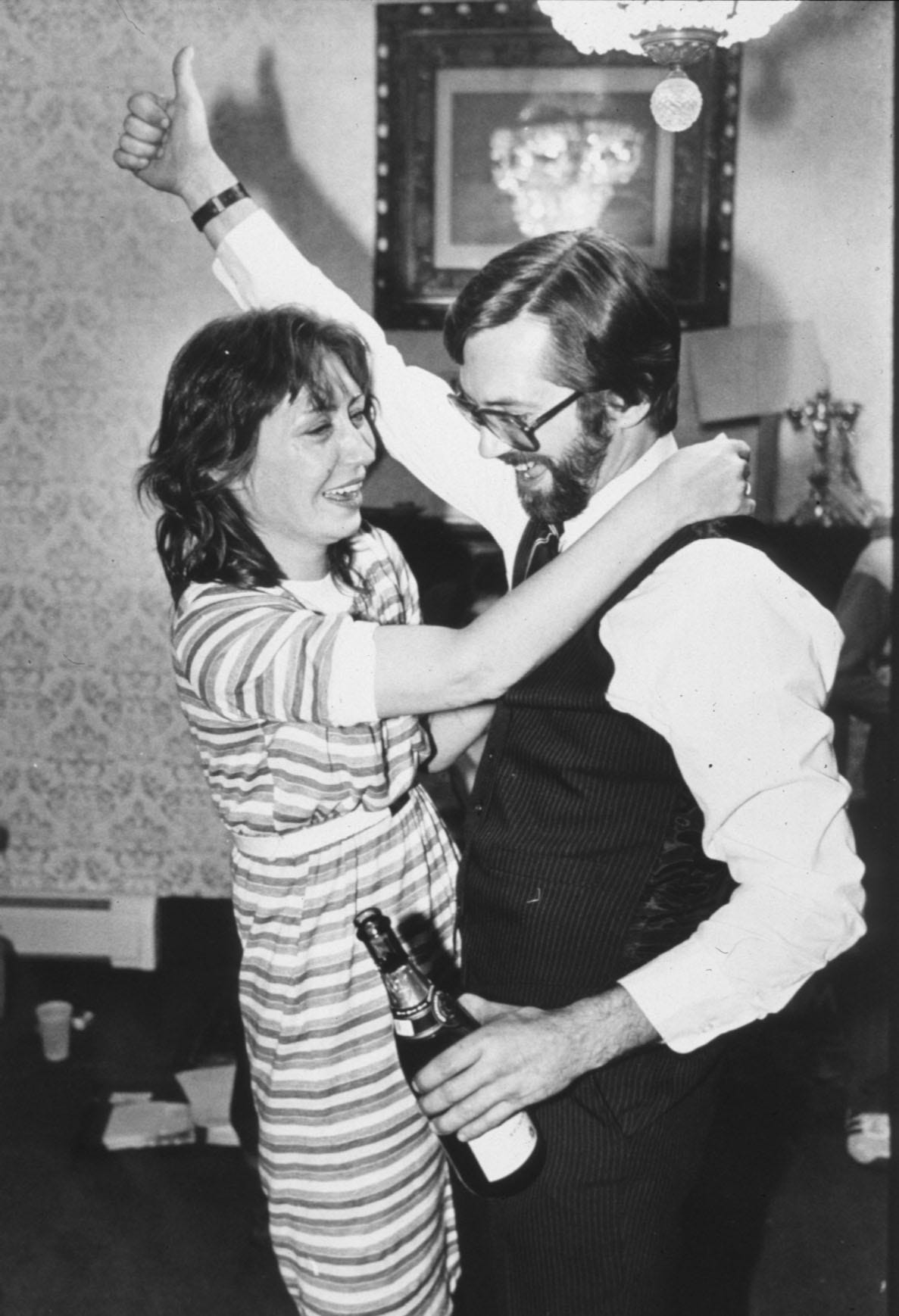

By and large, conversations did not end when people wanted them to. Only 17% of participants reported that their conversation ended when they first felt ready for it to end, 48% said it went on too long, and the remaining 34% said they never felt ready for it to end—to them, the conversation was too short!2

On average, people’s desired conversation time differed from their actual conversation time by seven minutes, or 56% of the conversation. That doesn’t mean they wanted to go seven minutes sooner or seven minutes later—it’s seven minutes different. If you just smush everyone’s answers together, all the people who wanted more cancel out all the people who wanted less, and it gives you the impression that everyone got what they wanted, when in fact, very few people did.

Participants thought their partners fared even worse: they guessed that there was a nine-minute (or 81%) difference between when the conversation ended and when the other person wanted it to end.3

~~~DISCUSSION~~~

These results surprised us. It wasn’t that conversations went on too long, necessarily—they mainly went on the wrong amount of time. And that’s extra surprising when you remember that we surveyed people about their most recent conversation, so they were overwhelmingly talking to people they know well, like a lot, and talk to all the time—spouses, friends, kids.

Still, this study had two big limitations. First, these conversations happened out in the wild, where they might have been ended by external circumstances. Maybe the “too long”s were, say, trapped on an airplane and unable to escape their unwanted conversation; maybe the “too short”s were having a lovely chat when their boss told them to get back to work.

And second, we only get to see one half of each conversation, so we don’t know how accurate participants were when they guessed their partners’ desires, nor do we know how people were paired up. Maybe, for instance, the “too long”s and the “too short”s were all paired with each other, and that’s why no one got what they wanted—they wanted different things.

To get around both of these limitations, we were going to have to bring people into the lab and—gulp—make them talk to each other.

STUDY 2

~~~METHOD~~~

We brought 366 people into the lab and paired them up. Our participants were a mix of students and locals in Cambridge, MA, and their defining characteristic was that they were willing to participate in a study for $15. We told them to “talk about whatever you like for as little time or as much time as you like, as long as it is more than 1 minute and less than 45 minutes.” We told them we had additional tasks for them if they finished early, so they would participate for the full hour regardless of how long they chose to talk. (We did this so that people didn’t think they could just wrap up after a minute and go home.)

~~~RESULTS~~~

Here’s the first crazy thing that happened: 57 of our 183 pairs talked for the entire 45 minutes. We literally had to cut them off so they could fill out our survey before we ran out of time. And that’s a problem, actually—we don’t know how long they would have kept talking if we hadn’t intervened. The whole point of this study was to watch people end their own conversations, and instead they made us do it.4 So we ultimately excluded these non-enders, but it turns out the results are the same with or without them. That itself is pretty weird, and I’ll come back to it in a minute.

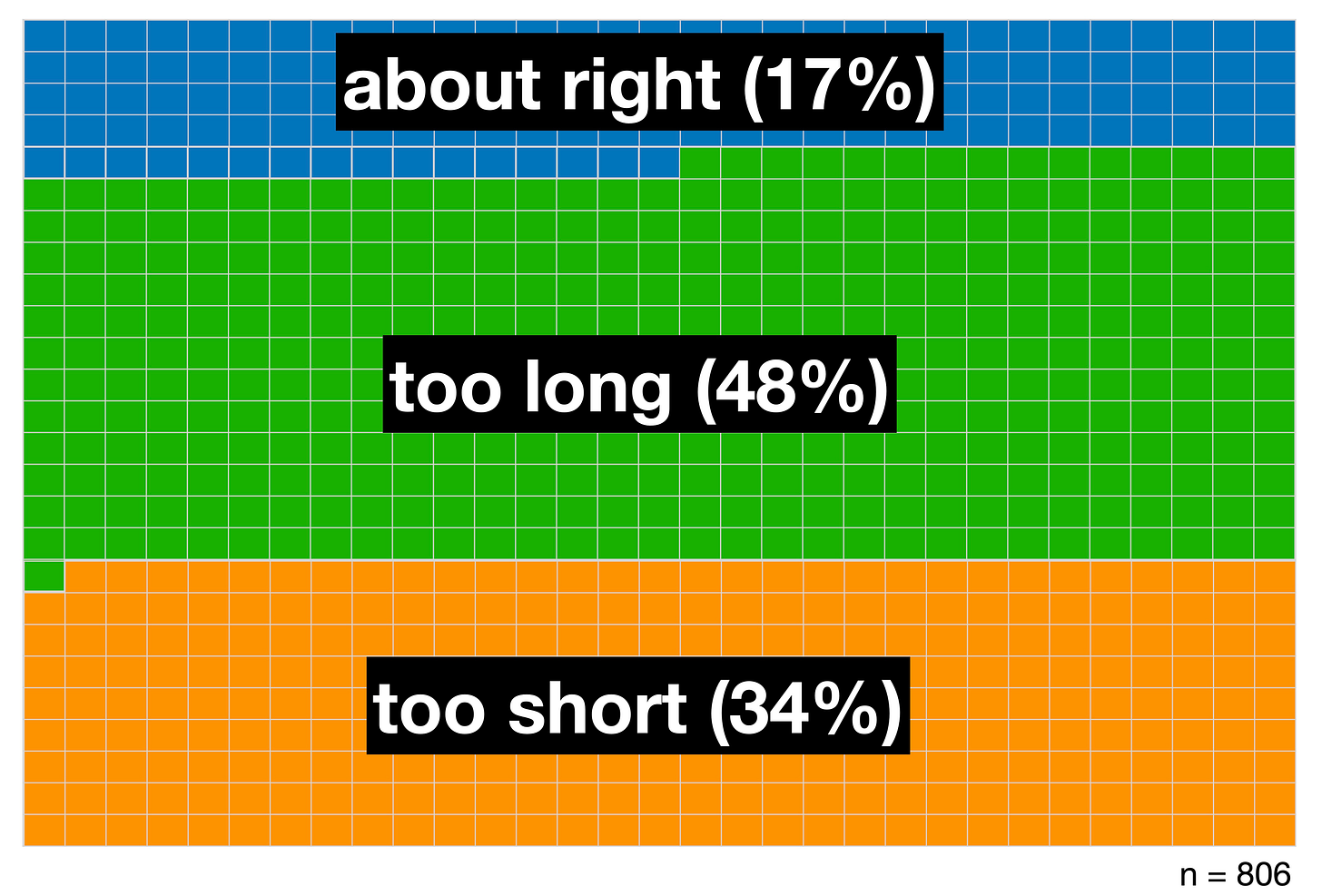

Looking only at people who ended their own conversations, once again, only a small minority of participants (16%) reported that their conversation ended when they wanted it to. 52% wanted it to end sooner, and 31% wanted it to keep going. On average, people’s desired conversation length was seven minutes—or 46%—different from their actual conversation length.

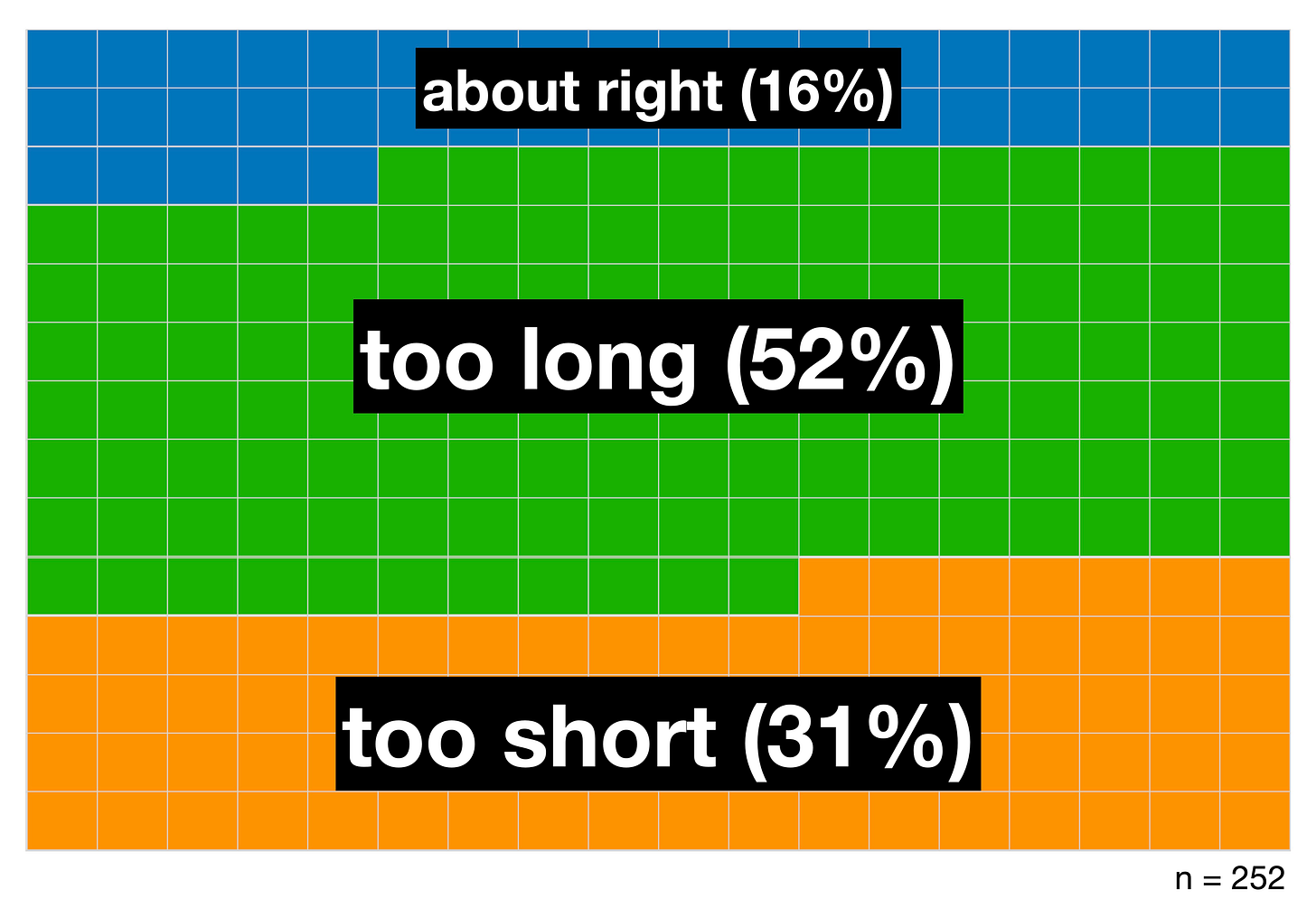

But now we have both sides of the conversation, so we can also see how people were paired. Was every “too short” partnered with a “too long”? Nope. In fact, almost half the time, both participants said “too long” or both said “too short”. Only 30% of conversations ended when even one person wanted it to end.

That means most pairs weren’t splitting the difference between their desires, nor were they waiting for one person to get tired and put an end to things. They were bumbling through their conversations, often blowing right past their preferred ending point, or never reaching it at all. We specifically told people to talk as long as they wanted to, but when they came out of the room, almost all of them said, “I didn’t talk for as long as I wanted to.”

So what happened? Why didn’t these conversations end when people wanted them to? Two reasons:

People wanted different things

In almost all cases, it was literally impossible for the conversation to end at a mutually desired time, because people’s desires weren’t mutual. People’s desired ending points differed by 10 minutes, or 68% of the conversation, on average. So at best, people had a considerable amount of dissatisfaction, and they had to figure out how to allocate it between them. But they couldn’t do that, because:

People didn’t know what their partner wanted

We had people guess when their partner wanted to leave, and they were off by 9 minutes, or 64% of the conversation, on average. So people really didn’t know when the other person wanted to go.

Incompatible desires create a coordination problem, and impenetrable desires prevent it from being solved. If you and I want different things, but I don’t know what you want, and you don’t know what I want, then there’s very little chance that either of us will get what we want.

~~~DISCUSSION~~~

Strangely enough, it didn’t seem to matter whether participants ended their own conversations, or whether we had to return at 45 minutes and do it for them. You’d think that if people could pick their own stopping point, they would pick something closer to their desires. But they didn’t.

Maybe that’s because a conversation is like a ride down the highway: you’re really only supposed to exit at certain times. But the exits themselves are pretty spread out, so you’re probably not going to be on top of one at the exact moment you start feeling ready to leave. Technically, you can get off the highway between exits, but you might have to drive through some bushes or crash through a wall—that’s what it feels like to, say, leave in the middle of someone’s story. So instead, you wait until the next exit comes (and you end up as a “too long”), or you get off before you really want to (and you end up as a “too short”). This strong set of conversational norms keeps things both orderly and somewhat dissatisfying.

The consequences for exiting at the wrong time are, in my experience, rather great. Once, I was hanging out with some friends, and there was a moment that felt to me like a lull in the conversation, and I had been feeling tired for a while and I felt like leaving, so I did. When I saw those friends again, they were all shaken. Apparently I had left at a super weird moment, like right in the middle of a thought, and all they could talk about was how weird my exit was. So at all future hangouts, I made sure to clear my departures with everyone, as if I was a commercial airliner asking air traffic control for permission to take flight.

“THIS CUP IS SO LOUD”

So far, I’ve made it sound like these conversations were awful. I recorded them and watched them later, so I can confirm: they were.

I opened one up just now, scrubbed to the middle of the video, and one guy was explaining how liquor licensing works in different states. In another, I found people desperately trying to find things to say about each other’s hometowns (“Are there...cities in Virginia?”). In another, two girls are talking about taking a year off of school, and one asks, “Oh, but don’t you have to re-do your financial aid paperwork?” and the other goes, “...I don’t get financial aid.” A silence pervades, then one of the girls starts playing with her coffee cup and goes, “This cup is so loud!”

But here’s something crazy: all three of those conversations went all the way to 45 minutes. We had to cut them off! And when they got out of the room, they reported enjoying their conversations a lot, usually scoring it a five, six, or seven out of seven. On awkwardness, they scored it a two or a three out of seven. (On average, participants in Study 1 enjoyed their conversations 5.03/7 and participants in Study 2 enjoyed them 5.41/7.)

If you’re surprised that people found it fun to be forced to talk to a stranger, you’re not alone. This didn’t make it into the paper, but we ran a little pilot study where we just asked people to guess the results from Study 2. They told us, essentially, that our study sounded like a pretty bad way to spend an afternoon. Participants estimated that nearly 50% of conversations would last 5 minutes or less—that is, most people would try to get out of there as soon as possible. In fact, only 13% of conversations were that short. (And remember, we’re excluding everyone who maxed out their conversation time.) They also thought only 15% of conversations would hit the 45 mark (actual: 31%), and they overall underestimated how much people enjoyed the experience.

THE AFTERMATH, OR, HOW I MISLED A MILLION PEOPLE

This article got a lot of attention when it came out, from the New York Times to late-night TV. According to Altmetric, it’s in the “top 5% of research outputs” in terms of public attention. This was mostly a bad thing.

Some of the articles were great, and some of the journalists I spoke to asked me sharp questions that I hadn’t considered myself. But lots of them got the core findings wrong. The headlines were like “CONVERSATIONS GO ON TOO LONG BECAUSE EVERYONE IS SO AWKWARD AND WEIRD”, which is what Dan and I thought we might find before we started running studies, but it’s not at all what the results turned out to be. It was as if the studies themselves were merely a ritual that allowed people to claim the thing they already believed, no updates or revisions necessary. Another article claimed that we studied phone conversations (we didn’t), and then other articles copied that article, until the internet was chockablock with articles about a study that never happened, a literal game of telephone about a telephone.

Some of this was just sloppy reporting for content mills that, I assume, paid like $30 for a freelancer to slap some quotes on a summary of the study. (This process has probably since been automated via ChatGPT.) But some of it was deliberate. One journalist was like, “So what you’re saying is that conversations go on too long, right?” I was like, actually, no! And I gave him this explanation:

It’s true that more participants said “too long” than “too short”, but if you average out everyone’s desired talking time, people wanted to talk a little longer than they actually did. But even that is misleading: the people who said “too short” had to estimate how much longer they wanted to talk, while the people who said “too long” were remembering when they wanted to leave. That means some people are making predictions that are theoretically unbounded—you could want to talk for days!5—while other people are reporting memories that are bounded at zero. As awkward as some of the conversations were, it’s not possible to wish that you talked for negative minutes. If you average all these numbers together, it’s not clear that the result is meaningful.

So did conversations go on too long? A lot of the time, yes. But a sizable minority ended before someone wanted them to end, and sometimes before both people wanted them to end! Mainly, conversations seem to end at a time that nobody desires. Obviously, this is all kinda complicated, and that why we put a question mark at the end of our paper’s title.6

After hearing that whole spiel, the journalist blinked at me and told me point blank, “Yeah, I’m gonna write about how conversations go on too long.” And he did. I’ll never know for sure, but it seems pretty likely that 100x more people read these articles than read the original paper, meaning the net result of my research was that I left the public less informed than it was before. Back in 2021, when this all went down, we would have called it an “epic fail”.

I know that scientists love to complain about science journalists: they take our beautiful, pristine science, and they dumb it down, slop it up, and serve it by the shovelful to the heaving masses of dullards and bozos! Nobody wants to admit that scientists cause this problem in the first place. Journal articles suck—they’re usually 50 pages of dry-ass prose (plus a 100-page supplement and accompanying data files) that must simultaneously function as a scientific report, an instruction manual for someone who wants to redo your procedure, a plea to the journal’s gatekeepers, a defense against critics, a press release, and a job application. So of course no one’s going to read them, of course someone’s going to try to turn them into something intelligible for the general public—who, by the way, really would like to know what’s going on in our labs, and deserves to know—and of course stuff’s gonna get messed up in that process. We let this system exist because, I guess, we assume scientists are so smart they could never speak to a normal person. But guess what, buddy: if you can only explain yourself to your colleagues, you ain’t that smart.7

Anyway, publishing this paper made realize that, no matter how much I tried to make my papers readable8, people are always going to treat them like they’re written in Latin, and they’re going to read the Google Translate version instead. So why not just speak in English? And that’s how this blog was born.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT GABBING

One upside of media attention is that I got to hear the kinds of questions—and the “less of a question, more of a comment, really”—that came up over and over again. So let me take a crack at ‘em:

I bet you’d get different results from me, because I come from a place/culture/family where people are super blunt!

Maybe! We studied people who happened to take a study online, or who wandered into our lab, which is not representative of all humanity. It’s possible that if you ran this in St. Petersburg or Papua New Guinea, you’d get different results. All we can say is that we couldn’t find any big demographic differences within our sample: race, gender, etc., didn’t make much of a difference. And we might have expected completely different results from people in the lab vs. people in their living rooms, but we didn’t find any, so it’s not a slam-dunk that changing the venue would change the data.

How do I know when someone wants to stop talking to me? Is there some kind of tell?

If there’s a tell, it’s not easily detectable by humans. All the things that people do when they’re trying to wrap things up are also things they just do, generally: break eye contact, shift around a little bit, deploy some “phatic” expressions like “yep” or “wow” or “that’s so crazy”. Even when someone gives the clearest possible sign that they’re ready to go (“Well, it’s been great talking to you!”), our results suggest their actual desired ending point could be long in the past or far in the future.

You should run a study where you give people an eject button that they can push when they want to leave!

We actually tried to do this. We planned to give people a secret foot pedal that they could tap when they were ready to go, so they could tell us live during the conversation rather than reporting it afterward. We ultimately scrapped this for three reasons:

Constantly thinking about the eject button would probably make the conversations weird and artificial

We didn’t think people would be able to pull off this level of spycraft during a conversation (they were stressed out enough just trying to talk to each other)

I ordered a foot pedal from Amazon but it made a telltale clicking noise

Can people really remember when they wanted to leave?

Maybe. We got the same results when we asked people immediately after their conversation ended (Study 2), and when we surveyed them after delays of several hours (Study 1). I’m sure there’s plenty of inaccuracy in people’s memories, but if it’s just noise, then it should cancel itself out. Either way, it doesn’t really matter. If conversations end exactly when people want them to, but then their memories immediately get overwritten, Men in Black-style, and they come to believe that their conversation didn’t end when they wanted it to, well, that’s the memory they’re going to have going forward, and that’s the data they’re going to use to make decisions in the future.

Okay, so how can I have better conversations?

If you, like many people, are worried that your next conversation will be a train wreck, let me assuage your doubts by confirming them: your conversation probably will be a train wreck. And that will be fine. I watched people wreck their trains several hundred times, crawl out of the burning rubble, and go “That was kinda fun!”

So probably the best advice is: worry less. Over the past 10 years, study after study has suggested that people are too anxious about their social skills. People think they’re above average at lots of stuff—driving, cooking, reading, even sleeping—but not conversing, and they disproportionately blame themselves for the worst parts of their conversations. They’re overly nervous about talking to strangers, and when they meet someone new, they report liking that person more than they think the person likes them in return. In fact, my friends and I once studied three-person conversations between strangers, and on average people rated themselves as the least liked person out of the group. Unless you have clinical-level social deficits, if you’re looking for life hacks to make your conversations better, you’re probably already too neurotic. It’s unlikely you’ll become more charming and likable by attempting to play 4D chess mid-conversation: “when do I want to leave, when do I think they want to leave, when do they think I think they think I want to leave”, etc.

One thing that surprised us, anyway, was that the people who said “too short” were just as happy as the people who said “just right”. (They were both happier than the people who said “too long”.) You might think that getting cut off would leave you feeling blue, but it’s actually kind of delicious to be left wanting more. So better to err on the side of leaving sooner—you can usually have more, but you can never have less.

Actually, come to think of it, there is one super practical tip you can take from these studies, which I’ve discovered from talking about them with many people in many different situations: for a pleasant conversation, avoid discussing this research at all costs.

When I first presented this data, people challenged the fairness of this question. What if someone felt ready to leave, but then the conversation picked up, and their feelings changed? It’s a good critique, so we ran another study where we asked people a followup question: if you felt ready to leave at any point, did you continue feeling that way until the end of the conversation? 91% of people said yes, they did. So it seems like we’re picking up a real desire to leave, rather than a passing thought.

We almost didn’t even give people the ability to tell us they wanted the conversation to continue longer than it did. I mean, if it ended, you must have wanted it to end, right? At the last second we were like, “Well, maybe there are some psychos out there who leave before they want to.” But it turns out the psychos outnumber us, so I guess the real psychos is us.

Note that these percentages are not simply the average desired conversation length divided by the average actual conversation length. We first divide each person’s desired length by the actual length, then we average. That’s why the percentage numbers seem to jump around a lot.

At least one pair of participants exchanged numbers after the study, so if nothing else we were running an extremely inefficient dating service.

In practice, we allowed participants to tell us that, at maximum, they wanted to talk for “more than sixty minutes longer”.

An indulgence we only won after a protracted fight with the journal, by the way. They don’t pay anybody to check your code, but they do pay someone to tell you that you’re not allowed to use special characters in the title of your paper.

Whenever people are like, oh, psychology is so easy to talk about because everybody understands it, I gotta laugh. Yes, we have less jargon than other fields. But jargon isn’t the thing that makes communication hard—you just back-translate the complicated words into normal ones. The hard part is making your ideas comprehensible, and that’s a tall order whether you’re working with particles or people. Try finding an “easy” way to talk about “people thinking about what other people thought the first person was thinking that the other person thought, as a proportion of the time they spent talking, but the absolute value of that”.

And we really tried! I think our paper is about as readable as a scientific paper could be, but that’s only because we went through two dozen drafts, and we still had to use phrases like “Absolute value of the proportional difference between actual duration and participant’s estimate of partner’s desired duration”. That’s because we had to include the level of information necessary to placate the pedants, not to inform the public.

Coincidentally, I just made a new goal a few days ago to try to talk to at least one stranger whenever I'm out and about. This happened because I was in the grocery store and saw a guy with a t-shirt from an art exhibit I was considering going to, and asked him about it. He went on WAY too long, 5-10 minutes, lots of details and repetitions about all the displays and which way to go in the exhibit, and I was thinking about how that rain coming in would probably soak me if I ever got out to my car, but in the end, I was so happy I talked with this funny little guy, because I met a memorable, enthusiastic character, and I want to do more of that.

Very interesting.

I've probably listened to more conversations than anyone alive, between recordings of jailhouse phone calls (to an outside party), recordings of police interviews, and a device I used to have that let me listen in on cell phones from passing motorists. Furthermore, I grew up in the era of landline phones where - no joke - it was nothing to have a six-hour chat with someone, sometimes even falling asleep while you're talking.

Obviously, I never interviewed anyone about their perception of whether the conversation went on for too long/short/etc. What I can tell you, however, is that most conversations seem incredibly boring to an outside observer but are critically important to participants.

First, the only conversations which seem engaging to outsiders are those in TV and films. As a screenwriter, I can tell you that these are VERY artificially constructed, and for good reason. Re-enacting a genuine conversation from a transcript would put the audience to sleep.

Second, one of the reasons why conversations seem boring to outsiders is because so much more is going on than an exchange of words aka "dialogue" aka what we think conversations are like due to film/TV. In some cases, it's literally passing the time with another person. You no longer feel alone. Other times, you're comparing and contrasting in order to find compatibility, hence the "oh where you from?" type of leading questions. In other words, it's kind of like an interview to see "can me and this person be friends/friendly?" Other times, it's almost like a mutual therapy session where you both get to release what's on your mind and the other person's job is just to listen.

Since you have recordings to review, go back and pick one at random. What you're gonna find is that there are short bursts where real/vital information is exchanged interspersed between long lulls. Someone might be talking about how "a cup is loud" and then boom, say something like "Hey, did I tell you I just got out of the hospital last week? Yep, cracked seven ribs."

Actually, it's quite a fascinating phenomenon, and now I'm kinda wishing I could eavesdrop on some conversations again because the rhythm and the give-and-take is VERY interesting once you learn how to interpret it. Hmm, maybe that's how I got into writing such good dialogue because the trick is to compress all the vital bits and trim out the (natural) lulls.