I wanted to be a teacher but they made me a cop

The conundrum in every classroom

Here’s one of the weirdest parts of teaching: students tell you when they have diarrhea.

To be clear, I don’t want to know when my students have diarrhea, and I don’t ask them. They just tell me. Every week, I get emails about upset stomachs, as well as strange coughs, sick grandmothers, suicidal friends, canceled flights, and family emergencies.

One student cornered me after class to tell me he’s been absent so much because he’s both getting divorced and starting a business. (“Please don’t worry about it,” I said.) Another time, a student apologized for missing class; she had just found out about a mass shooting near her home. (“Please don’t worry about it.”) Once, I listened, aghast, to a student explain that she’d unfortunately have to miss class to be at her child’s life-saving surgery. (“PLEASE don’t worry about it!!”)

Until recently, this all seemed unfortunate but sensible. Students want points, I have the points, and so they’ll divulge whatever details they think will get me to cough those points up. Some students are probably lying, and part of my job is to tell the fake diarrheas and divorces from the real ones.

But as I enter my final grades and finish up my teaching job at Columbia, I’m struck by a strange thought: what am I doing? Why am I the guy that people tell when they have digestive distress? Why do we have an education system where it’s reasonable for students to debase themselves in exchange for made-up points?

MR. TWO JOBS

My teaching job, it turns out, is actually two jobs.

One job is instruction. Students and I enter the same room at scheduled times, I perform a series of actions, they perform a series of responses, and then the students leave the room more educated than they were before. This job rules. I like it when my students go “ohh!” and “I never thought about it that way” and “I get it now!” I like when they email me, years later, to tell me how they used something they learned in class. This all makes sense. In fact, I thought this would be my only job.

But I realize now that I have a second job, which is evaluation, or gatekeeping, or, most specifically, point-guarding. I’m supposed to award "points" based on what students do in my class. Students try to acquire as many points as they can, and I try to stop them from obtaining points too easily. My employers expect me to ensure that, at the end of the semester, some students have more points than other students. At Columbia Business School, this was explicit: only half of students were supposed to receive an “H,” the highest grade.

This part of my job makes no sense. For one thing, point-guarding makes students miserable. They're always stressed about how many points they have, and how they can get more. They’ll memorize useless information, stay up all night writing essays they hate, and even steal their classmates’ work in a desperate attempt to score points. And, of course, they’ll say anything to get points, including “Hey prof, I have diarrhea."

For another thing, point-guarding makes me miserable. I have to decide whether students are telling the truth about their misfortunes, which leads me to entertain such nasty thoughts as, “I wonder if their grandma really died.” Students beg me for more points, or berate me for not giving them enough. All this for points that are made up! I don’t care about the points! Give ‘em all a million!

Worst of all, the things that make me a better instructor often make me a worse evaluator, and vice versa. Instruction is collaborative: students want to learn, and I want them to learn, too. Evaluation is adversarial: students want the points, and I have to make sure they don’t get too many. Evaluation forces me to flatten everything I teach into something that can be tested, and it encourages students to ignore everything that isn’t on the test. Plus, instruction and evaluation compete for time: every minute I spend ranking students is a minute I’m not teaching them, and a minute they’re not learning.

(It seemed normal at the time, but now that I think about it, it’s pretty depressing that whenever I got a syllabus in college, 25% of it was about the content of the class, and 75% of it was about how I could acquire points.)

This whole evaluation thing seems pretty bad, so we should only do it if we have a good reason. Do we?

WHAT ARE GRADES FOR?

Nobody ever told me why I’m evaluating my students. In fact, in the final year of my PhD, I became the person who taught grad students how to teach, and I never told them why they were evaluating their students. We all just took it for granted: “Ah yes, the ancient, sacred tradition of assigning people a number based on how many classes they attended and how many multiple-choice questions they answered correctly.”

But everybody seems to be doing it, so maybe they know something I don’t. Could there be any benefit to pairing evaluation with instruction?

I don’t think so, because every argument sounds pretty lame:

“Grades are for motivating students.”

If my class is so boring that I have to devise an additional carrot-and-stick system to get students to pay attention, the problem is my class is boring.

Humans are intrinsically interested in tons of stuff. They’ll read a hundred books about dinosaurs, memorize the makes and models of classic cars, practice the clarinet for hours every day—all because they like it. For goodness’ sake, some people will listen to baseball on the radio, an activity I find so torturous I think it should be outlawed by the Geneva Conventions. The idea that people don’t care about learning is a dumb cousin of the even dumber idea that people are stupid.

So if people need some extrinsic motivation to engage in my class, one of two things might be happening. Maybe they’re just not interested in what I have to offer. That’s fine! They should take a different class. More likely, though, the problem is me: I'm somehow subverting people’s natural curiosity. Maybe I’m doing that by inflicting evaluation on my students—rules! points! policies!—instead of just showing them what they came to see. When every class begins with a ~20-page description of the academic panopticon students have to live inside for the next semester, I dunno, maybe that takes some of the fun out of learning?

“Grades are for giving feedback to students on how well they’re doing.”

Feedback and evaluation look similar but are, in fact, nothing alike. Here’s a handy chart I made:

So you don’t have to give students grades in order to give them feedback. In fact, grades can get in the way. Whenever I got an essay back in college, I would always flip to the final page to look for the grade, feel the appropriate emotions (“I’m the smartest guy who ever lived!!”/“I’m an idiot, destined to die in a hole!”), and basically ignore the comments, because the grades counted and the comments didn’t.

“Grades are for separating the good students from the bad students."

I’m not actually interested in doing this. What am I going to do, send the good students to heaven and send the bad students to hell? Besides, what makes a student “good”? Some students make great comments in class but turn nothing in. Some students are getting divorced right now and can’t really focus on school. I want to teach every kind of student the best that I can, and maintaining a “naughty” list and a “nice” list only gets in my way.

CHRIST IS BACK AND THEIR NAME IS CAM

Grading students doesn’t make me any better at teaching them, and it sure seems like it makes me worse. But maybe I’m doing it wrong. Could there be some perfect mix of teaching and grading where they turn into a delicious cocktail rather than a toxic sludge?

I don’t think so. I’ve lived through, implemented, and seen up close various experiments in evaluation, and none of them seem to even come close to solving the instruction/evaluation conundrum. For instance:

Grade deflation

Princeton University, where I went to college, decided it wasn’t doing evaluation hard enough. “The GPAs are too damn high!” the deans said. So they instituted a policy of “grade deflation”: professors were only supposed to award As to 35% of students, and everyone else had to make do with a B+ or lower.

Everybody hated this. Professors chafed at administrators peering into their grade books. Students wailed about getting a 93% deflated to a B. Other universities continued handing out 4.0 GPAs to most students, which probably gave them an edge over their Princeton peers when applying for jobs, scholarships, and graduate school (I know, boo hoo). Princeton ditched grade deflation in 2013, its decade-long experiment deemed a complete failure.

Apparently reinflating grades didn’t make anything better. I was back on campus a few months ago, and I asked some professors if student anxiety had subsided a bit since the demise of grade deflation. “Oh no,” they said. “Now students are fretting about the third decimal place of their GPAs because grades have become so bunched up at the top."

“Suppressing” grades

When I taught at Columbia Business School, I was told that students’ transcripts were “suppressed,” meaning that the university would never tell anyone else how well a student had done at CBS. Surely if students’ grades were secret, we could basically ignore evaluation and focus on instruction.

In practice, this made zero difference. On the first day of class, I would explain to students that, although I don’t see the value in grades and they are apparently secret anyway, I was contractually bound to give them. I told students they shouldn’t care about these grades, and they should instead “define success” for themselves, which also happens to be one of the key tenets of good negotiation. “Grades are Monopoly money,” I explained, “And if you, for instance, claim that you’re sick when you’re really not, all you’re doing is stealing Monopoly money.” This always got a big laugh, and then minutes later I’d have students come up to me after class saying, “But seriously, how do I get some of that Monopoly money?”

I was at first surprised, but I shouldn’t have been. It doesn’t matter if your grades are “suppressed”—if a potential employer asks to see a record of your business school grades, are you going to lecture them on Columbia’s transcript policy and risk not getting a job, or are you going to screenshot your unofficial transcript and email it to them?

No grades, just words

At Hampshire College, founded by hippies in 1970, there are no letter grades. Instead, at the end of the semester, your professor writes an 800-1200 character blurb about you, with notes like “Leaf writes at the level of an advanced graduate student,” or “Mordecai didn’t show up to class most days.” They call these “narrative evaluations.”

I visited Hampshire a few weeks ago to see my friend Ethan (coauthor of Things Could Be Better) and meet some of his students. I asked them about their wonky alternative evaluation system, and overall they seemed to like it—nobody said they’d rather get letter grades on their transcripts instead of little stories. But these students had all chosen to attend a hippie school in the woods, so that’s not surprising.

Still, replacing letters with words didn’t solve the fundamental problems with evaluation. For one thing, students informed me, some professors still use evaluations like a cudgel: “If you don’t do a good job on your final project, I won’t give you an eval.” Narrative evaluations let professors’ biases run wild—they can heap praise on their favorite students and withhold it from others, no matter how well those students did. This can creepily reward students for sucking up to their instructors. And one student pointed out that while you can max out your grade in a letter-grade system, there’s theoretically no limit to how much you could improve your narrative evaluation (“Cam is so amazing that I can only assume they are the second coming of Christ”), which encourages high-achieving students to exhaust themselves in the hopes of being described with slightly nicer words.

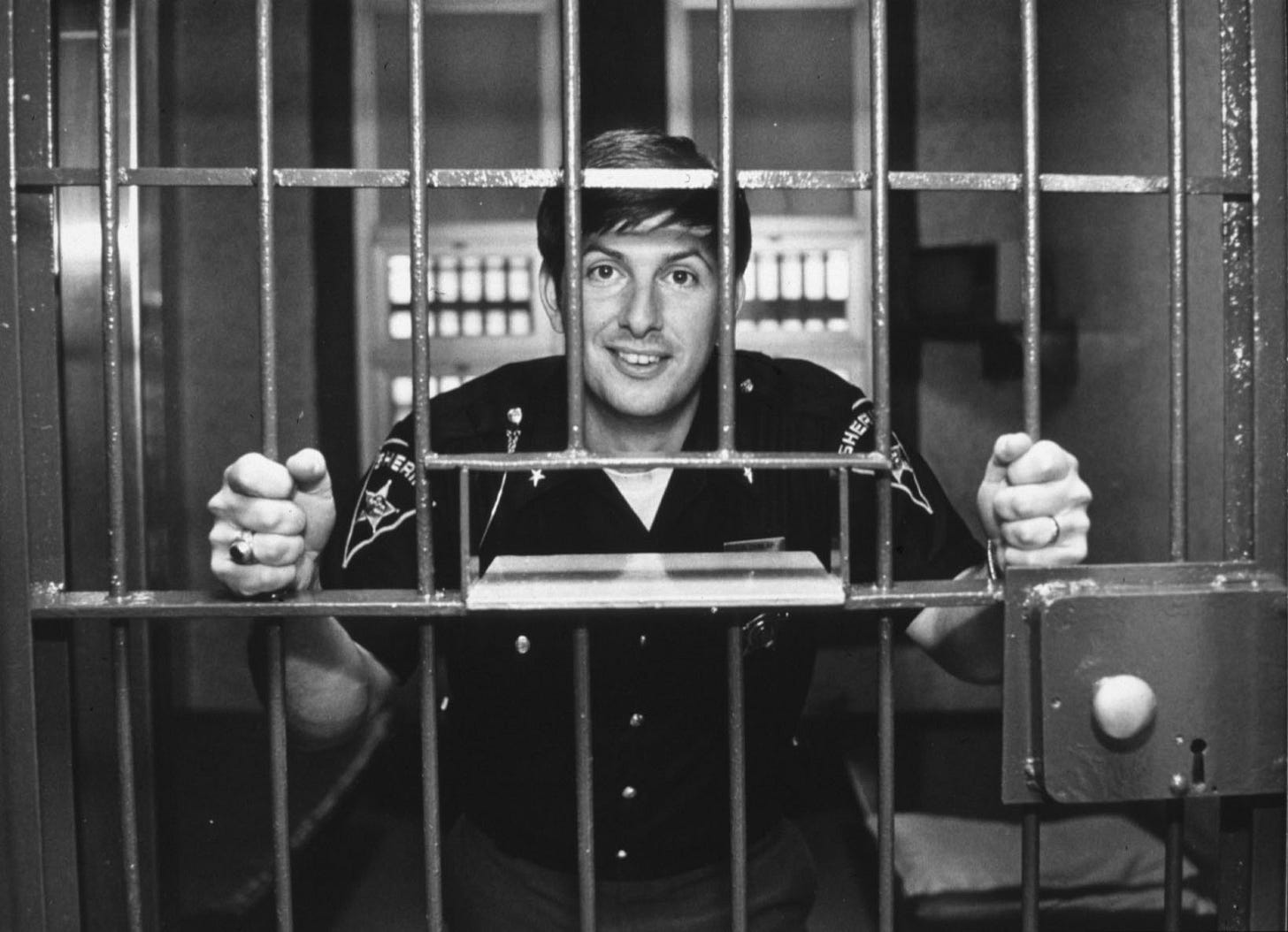

Grade harder, grade softer, grade with words rather than numbers, hide the grades entirely—none of it works, because the problem was never the grades themselves. The problem was trying to be both a teacher and a cop at the same time.

STILL WAITING FOR MY CHECK, HORTICULTURALISTS

Ranking my students doesn’t help me teach them, so I have no interest in doing it. But I understand why other people want me to do it.

In fact, they’re counting on it. Businesses need to decide who to hire, graduate schools need to decide who to admit, and scholarships need to decide who to fund, so they’d all appreciate it if I identified the best students for them. I can’t help but notice, however, that none of those organizations pay me. They pay headhunters, hiring managers, and program officers, after all, so it's a little weird for me to do these people’s work for them. It's especially egregious for these businesses and schools to force students to pay huge sums to get themselves evaluated by me, a guy who just wants to teach them psychology but ends up playing point guard instead.

Why is this all backwards? Shouldn’t the people using these evaluations be the ones doing the work and shouldering the cost?

Three things are happening here. One: the gatekeepers who guard selective opportunities know that they can demand anything of applicants. Why go to all the trouble of trying to figure out how smart someone is when you can make them spend four years and ~$150,000 proving it to you?

Two: everyone’s assuming that my evaluations are all-purpose. But they aren't. Want to know who you should send to Romania on a Fulbright, who you should hire as a personal assistant, or who you should admit to your Master of Horticulture program? Don’t ask me; all I did was teach them psychology. Maybe they hated my class but they’d love Romania. Maybe they understand the mind but they don’t get plants. Maybe they didn’t show up much because they were busy divorcing their terrible husband. I wasn’t trying to help people pick candidates; I was merely fulfilling my contractual obligation to count how many made-up points my students got.

And three: people assume evaluation isn’t that hard. You’re just keeping track of points, aren’t you? If that’s what you think, no wonder you also think it’s fine to outsource the job to people who are doing it part-time and halfheartedly.

There’s not much that can be done about #1, but #2 and #3 would change pretty quick if people had to see evaluation up close, really stick their noses in it and take a big whiff. Because then they’d realize that evaluation, when taken to its logical end, smells a lot like prison.

PRISON WARDENS IN TWEED

Every level of our education system mixes instruction and evaluation, but there’s a place you can go to get pure, uncut evaluation without an ounce of instruction: your local testing center. The alphabet soup of standardized tests—the SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, LSAT, etc.—offers the promise of a grade without the hassle of learning.

These are not fun places to be. When I took the GRE ten years ago, the testing site was like a maximum security prison. A man wanded me down with one of those handheld metal detectors (What were they looking for? An iron ball engraved with the quadratic formula?). I could only bring snacks in a clear plastic bag, apparently so they could examine my granola bars. I had to empty my pockets into a locker and enter the testing room with nothing but my wits and the clothes on my back. A prison guard—sorry, “proctor”—patrolled the rows of cubicles every 15 minutes, scanning for any signs of cheating.

These days, thanks to the wonders of technology, you are allowed to take the GRE in a little prison you construct inside your own home, and a digital proctor watches you the whole time through your webcam. To make this domestic panopticon work, you have to abide by rules like:

Your ears must remain visible throughout the test, not covered by hair, a hat or other items. Religious headwear is permitted if your ears remain visible during the test.

You must be dressed appropriately for your test. You will be monitored via camera by the proctor, and your photo will be shared with institutions that receive your scores.

Avoid wearing such items as jewelry, tie clips, cuff links, ornate clips, combs, barrettes, headbands and other hair accessories.

Camera must be able to be moved to show a 360-degree view of the room, including your tabletop surface, before the test

You must sit in a standard chair; you may not sit or lie on a bed, couch or overstuffed chair.

Wanna wear your lucky barrette while taking the GRE? Sorry, pal, you’re outta luck!

Apparently this is all standard for the unfortunate generation who came of age during the pandemic. They’ve gotten used to taking tests at home using monitoring software like Proctorio, which sounds like a Batman villain who is hellbent on giving every human a rectal exam. As Texas Tech, one of Proctorio’s happy clients, explains:

During the exam, a system of computers captures your movements and sends your video and other data to your instructor for review. Proctorio will flag activity that might not be allowed. Your instructor will then be able to review the video and data to decide if any action is necessary.

This is where you end up when you optimize for evaluation: a dystopian police state. You can’t evaluate students if some of them are cheating, so you pat them down and surveil them. You have to make sure no one has an unfair advantage, so you force everyone to answer the exact same questions in the same amount of time. Those questions must have clear, objective answers, no gray areas allowed. And they have to be pre-tested so that you can toss out anything too easy, too hard, or too biased against one kind of student, and so that you can produce an appropriate mix of questions that in turn elicits a wide distribution of scores.

As an educator, I want no part of this. I don’t want surveillance videos of my students. I don’t care if they wear top hats and sit in overstuffed chairs. Hell, I’d let ‘em wear all the ornate clips they want! Enforcing these rules only makes me worse at teaching. If you’re into this stuff, guess what: you’re not a teacher, you’re a cop.

HELP! I’M DROWNING! CALL A MATHEMATICIAN!

But look, we need some evaluation. People have different talents, and they should get opportunities that tap those talents, not just because it benefits them, but because it benefits everybody. If I’m drowning (God forbid), I want to be saved by a lifeguard who’s good at swimming. If I get hit by a bus (God forbid), I want to be operated on by someone who's good at surgery. If I take a math class (God forbid), I want to learn from someone who’s good at math. For that world to exist, someone, at some point, has to evaluate people on their swimming, surgery, and math.

So if we need to both teach people and grade them, what should we do?

One solution is to separate instruction and evaluation. Let teachers be teachers and cops be cops. Professional evaluators have the skills and time to ensure their assessments are reliable, unbiased, and cheat-proof; instructors doing evaluation on the side toss a few essay questions into a Word document and hope for the best. If getting evaluated means visiting a police state, it’s better to be a tourist than a resident—spending a month studying for the SAT and an afternoon taking it is miserable, but spending a lifetime in classrooms that double as prisons is even worse.

Doing evaluation on its own would have a few major benefits. First, it would force us to take evaluation seriously. The people sitting at the switchboards of life, directing where other people get to go, have a sacred responsibility to get things right. They deserve skepticism and scrutiny. Most importantly, they should be good at running the switchboards. But we can’t hold them accountable unless we treat evaluation as its own beast, rather than something you can get for free from a transcript.

Second, we’d see how hard evaluation is, and maybe we’d do it better. Evaluation, like all forms of gatekeeping, is a wicked problem. People will figure out how to game your test. Assess them on Friday and they’ll forget everything by Monday (I have some ideas about that). If all else fails, they’ll tell you they have diarrhea. The problems that arise in evaluation are so diabolical and interesting that I spent two of the earliest Experimental History posts trying to untangle them: Grant funding is broken. Here’s how to fix it and Against All Applications.

And finally, if we made evaluation its own thing, we’d see how nasty it is, and maybe we’d do less of it. We have to pick the lifeguards and the doctors and the mathematicians—fine. But then we should stop. Every time we rank one another, we lose a little humanity. The people who end up on top become more arrogant, the people who end up at the bottom become more indignant, and the people doing the ranking become more callous. Evaluation is like X-rays: small doses are helpful, but large doses are lethal.

Evaluation is built on two vexing questions. One is philosophical: "Who deserves to be on top?” The other is practical: “How do we identify those people?” These questions shouldn’t just make us scratch our heads; they should make us search our souls. You can’t answer these questions if you don’t ask them, and you won’t ask them if you’re splitting your time between teaching and policing. I don’t know the answers myself, and I definitely don’t want to be a cop, and that’s why I want out. Most of all, though, I don’t want people to tell me they have diarrhea.

Great post! I started a full-time teaching job at UCSD this year and so much of this resonates. In addition to "cop" I'd add something like "legislator": because classes are often >300 students, I spend too much time worrying about how to design "general" course policies that are the least bad while also trying to balance not over-loading myself or my teaching team with administrative work. But this still means that a non-trivial % of my time is (as you said) spent responding to student requests for exceptions, etc., most of which seem entirely understandable and none of which I'm really that interested in litigating. It also means deciding how/whether/when to enforce semi-arbitrary policies, where an exception makes sense in each particular case, but where (because of the class size) it still feels like I need *some* general rule.

I think I agree with 99% of what you've written—I do, however, think that some kind of external motivator can be really helpful. I'm not sure it's grades per se. But in my own life, for example, there are things that I *want* on some level to learn (and will ultimately enjoy knowing) but which I know I don't have the discipline to sit down and push myself to do. Those things are most useful to have classes for, and in turn it's helpful to have some kind of external push to attend those classes and do the work. But that said:

1) I agree grades may not be the right approach;

2) I especially like the idea of separating instruction from evaluation;

3) It's also entirely possible that the reason I require so much external motivation in these cases is because I've been trained in a system that centers grades and evaluation! Maybe there's a better way forward.

The other challenge with separating instruction from evaluation (which I think is broadly good) is that, at least in my experience, you sometimes see resistance from teachers. Now, that's in part because historically it's been tied to things like evaluating *teacher* performance (evaluations all the way down!) and even school funding. But it is a potential obstacle.

For everyone nodding along to this (like me): there is growing and global movement of educators to do grading less and/or differently, mostly under the banner of 'ungrading' (e.g. see https://www.jessestommel.com/tag/ungrading/ and https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/case-grades/ for two foundational authors). There is also a growing body of work showing that "compared to those who received comments, students receiving grades had poorer achievement and less optimal motivation" (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01443410.2019.1659939?journalCode=cedp20)