The Decline of Deviance

Where has all the weirdness gone?

People are less weird than they used to be. That might sound odd, but data from every sector of society is pointing strongly in the same direction: we’re in a recession of mischief, a crisis of conventionality, and an epidemic of the mundane. Deviance is on the decline.

I’m not the first to notice something strange going on—or, really, the lack of something strange going on. But so far, I think, each person has only pointed to a piece of the phenomenon. As a result, most of them have concluded that these trends are:

a) very recent, and therefore likely caused by the internet, when in fact most of them began long before

b) restricted to one segment of society (art, science, business), when in fact this is a culture-wide phenomenon, and

c) purely bad, when in fact they’re a mix of positive and negative.

When you put all the data together, you see a stark shift in society that is on the one hand miraculous, fantastic, worthy of a ticker-tape parade. And a shift that is, on the other hand, dismal, depressing, and in need of immediate intervention. Looking at these epoch-making events also suggests, I think, that they may all share a single cause.

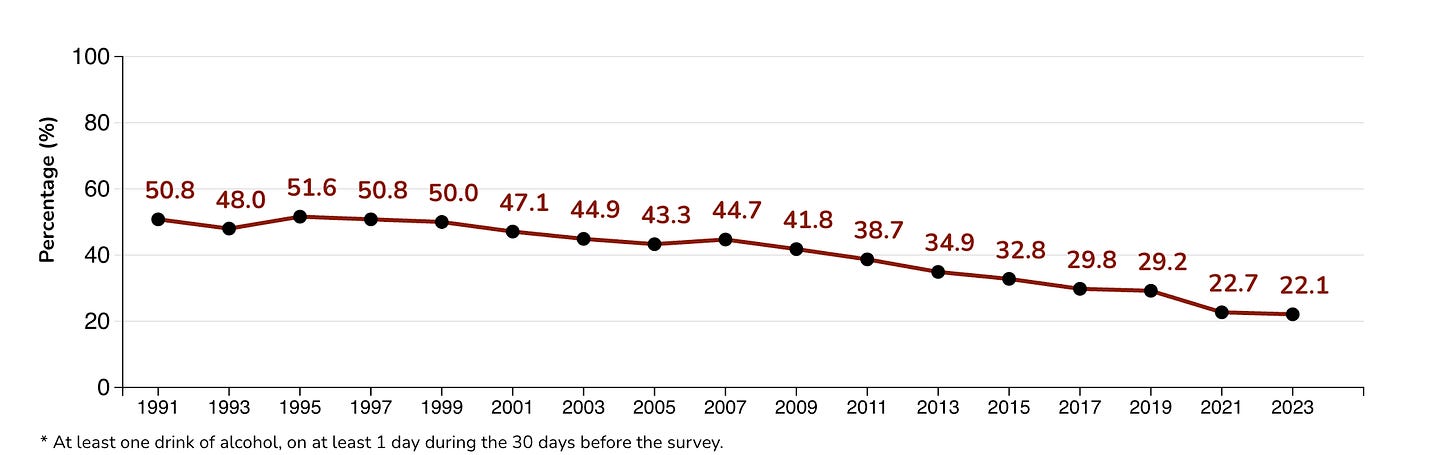

1. THE DISAPPEARING MISCREANTS

Let’s start where the data is clear, comprehensive, and overlooked: compared to their parents and grandparents, teens today are a bunch of goody-two-shoes. For instance, high school students are less than half as likely to drink alcohol as they were in the 1990s:

They’re also less likely to smoke, have sex, or get in a fight, less likely to abuse painkillers, and less likely to do meth, ecstasy, hallucinogens, inhalants, and heroin. (Don’t kids vape now instead of smoking? No: vaping also declined from 2015 to 2023.) Weed peaked in the late 90s, when almost 50% of high schoolers reported that they had toked up at least once. Now that number is down to 30%. Kids these days are even more likely to use their seatbelts.

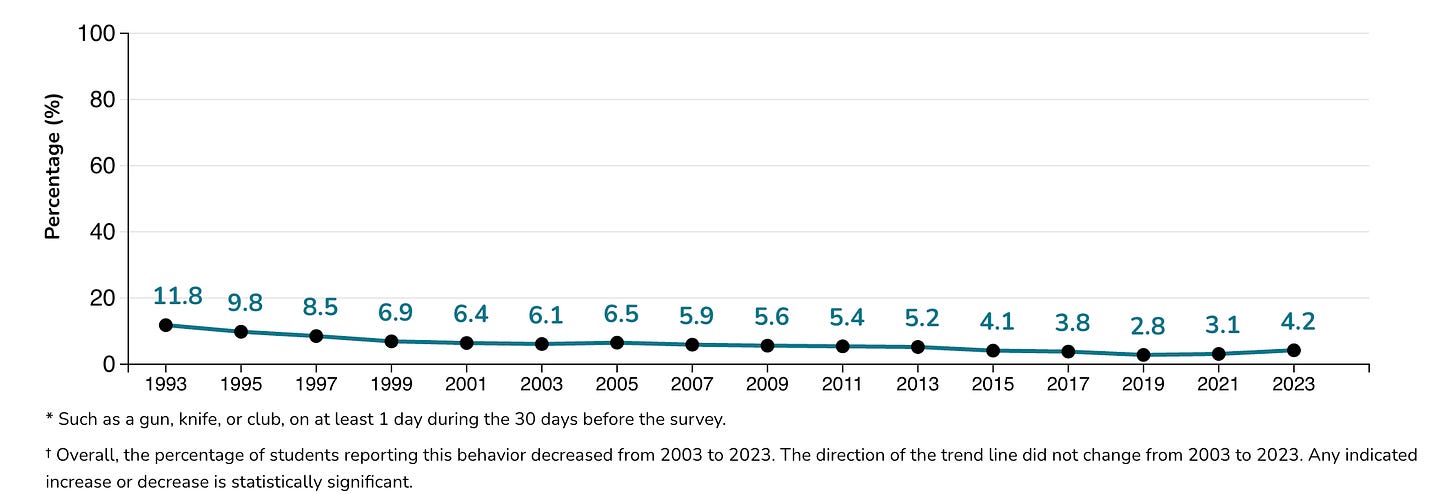

Surprisingly, they’re also less likely to bring a gun to school:

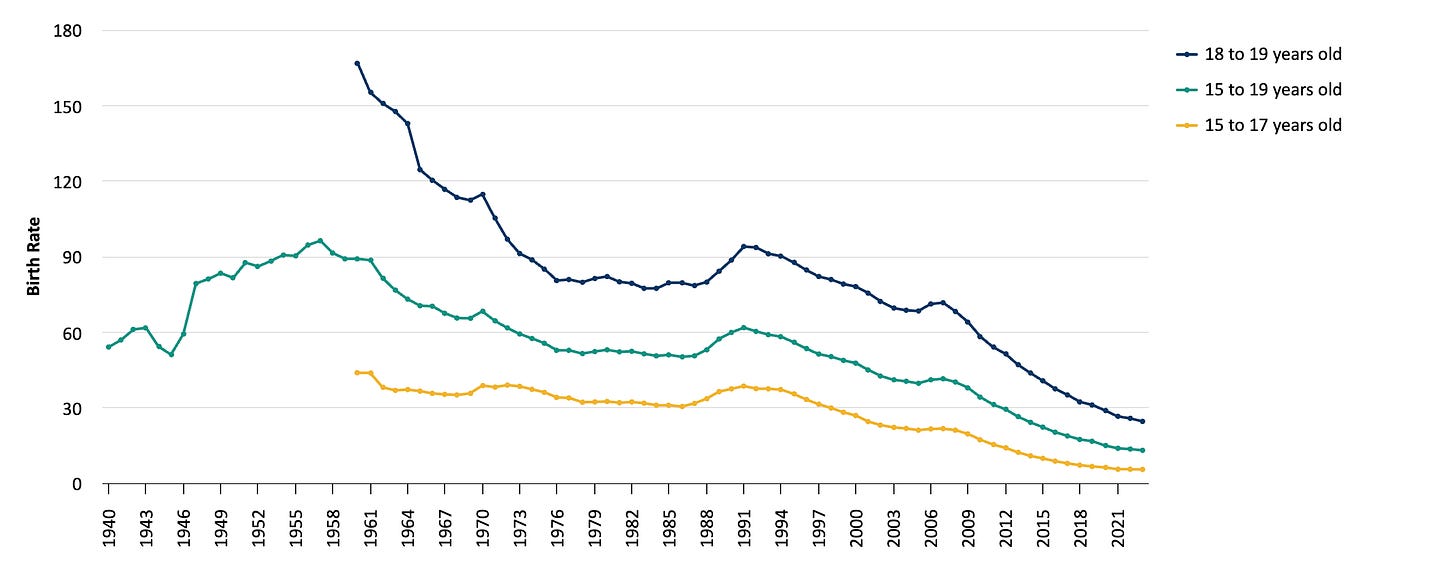

All of those findings rely on surveys, so maybe more and more kids are lying to us every year? Well, it’s pretty hard to lie about having a baby, and teenage pregnancy has also plummeted since the early 1990s:

2. THE GROWN-UPS HAVE FALLEN IN LINE

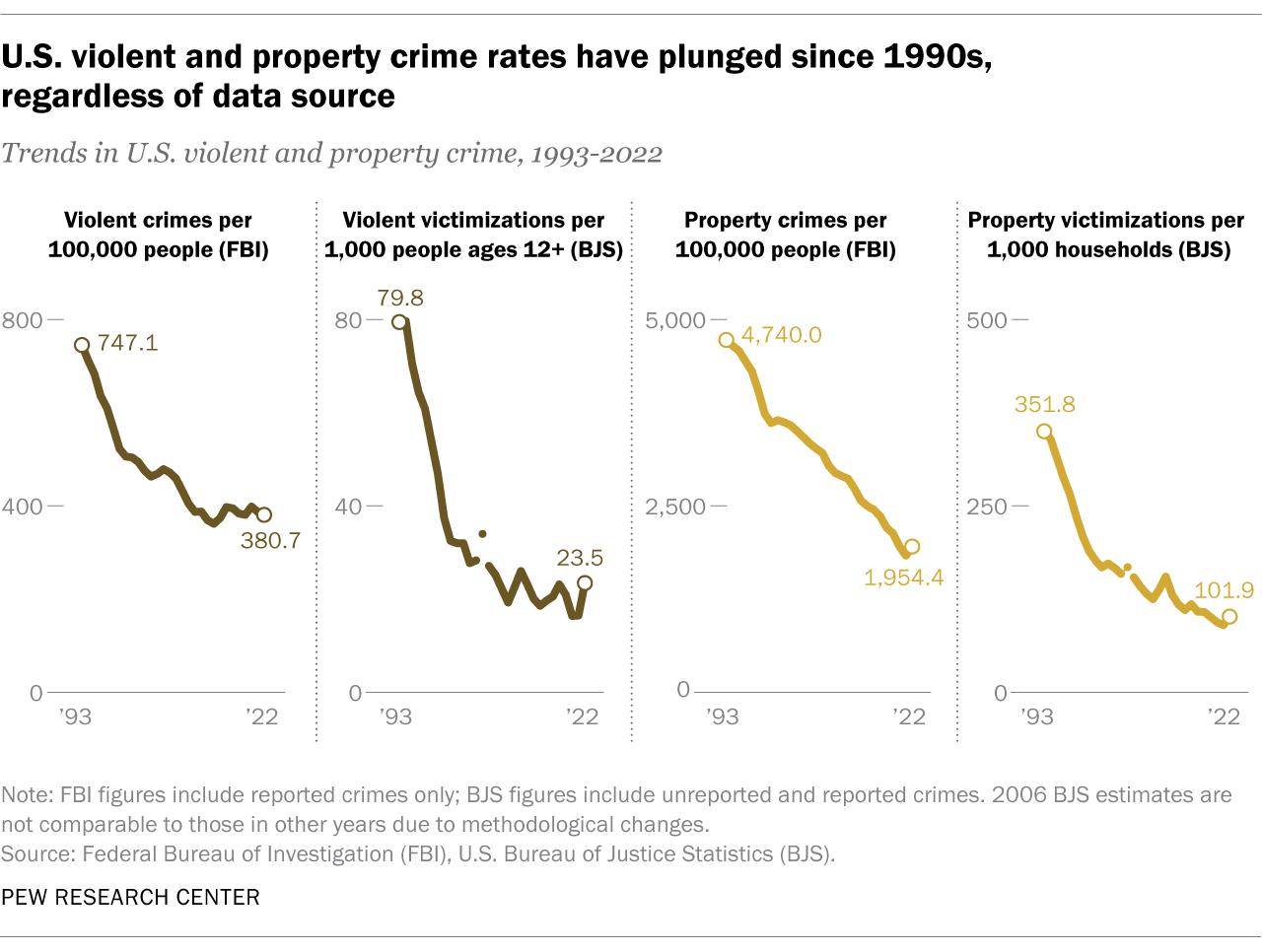

Adults are also acting out less than they used to. For instance, crime rates have fallen by half in the past thirty years:

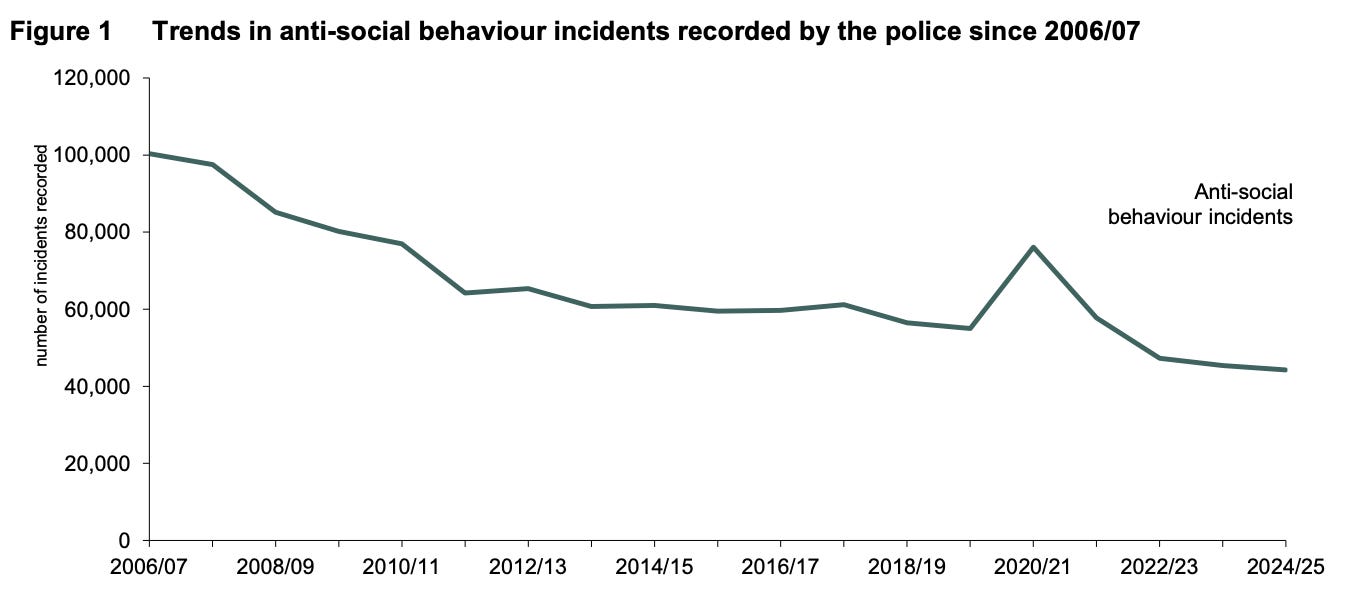

Here’s some similar data from Northern Ireland on “anti-social behavior incidents”, because they happened to track those:

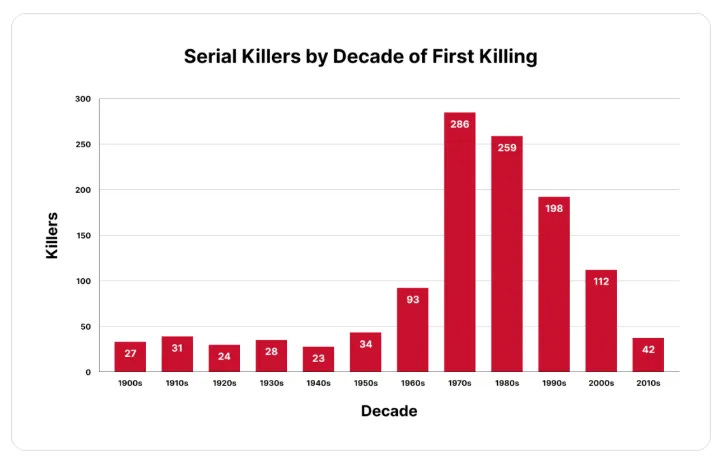

Serial killing, too, is on the decline:

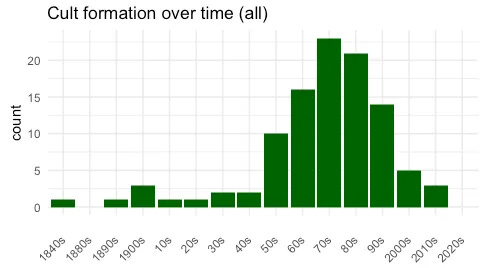

Another disappearing form of deviance: people don’t seem to be joining cults anymore. Philip Jenkins, a historian of religion and author of a book on cults, reports that “compared to the 1970s, the cult issue has vanished almost entirely”.1 (Given that an increase in cults would be better for Jenkins’ book sales, I’m inclined to trust him on this one.) There is no comprehensive dataset on cult formation, but Roger’s Bacon analyzed cults that have been covered on a popular and long-running podcast and found that most of them started in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, with a steep dropoff after 20002:

Crimes and cults are definitely deviant, and they appear to be on the decline. That’s good. But here’s where things get surprising: neutral and positive forms of deviance also seem to be getting rarer. For example—

3. PEOPLE ARE STAYING PUT

Moving away from home isn’t necessarily good or bad, but it is kinda weird. Ditching your hometown usually means leaving behind your family and friends, the institutions you understand, the culture you know, and perhaps even the language you speak. You have to be a bit of a misfit to do such a thing in the first place, and becoming a stranger makes you even stranger.

I always figured that every generation of Americans is more likely to move than the last. People used to be born and die in the same zip code; now they ping-pong across the country, even the whole world.

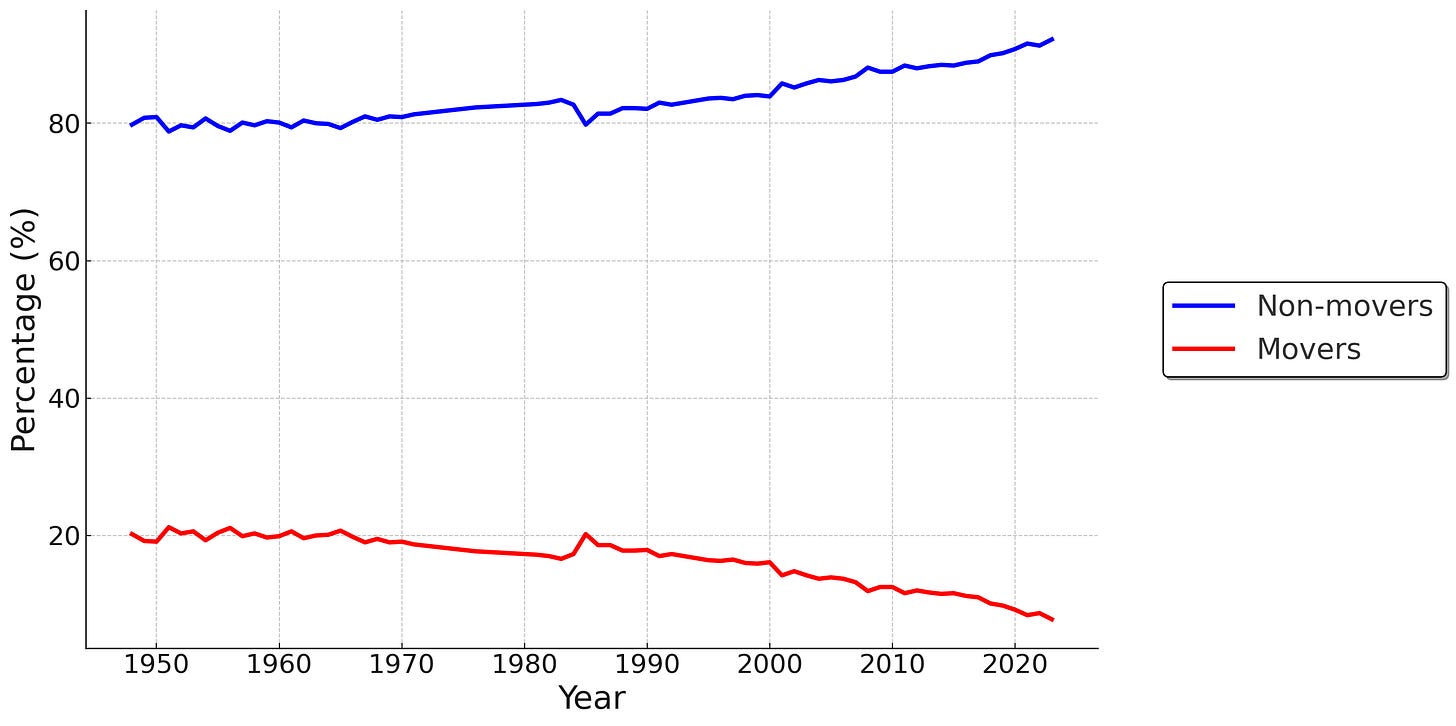

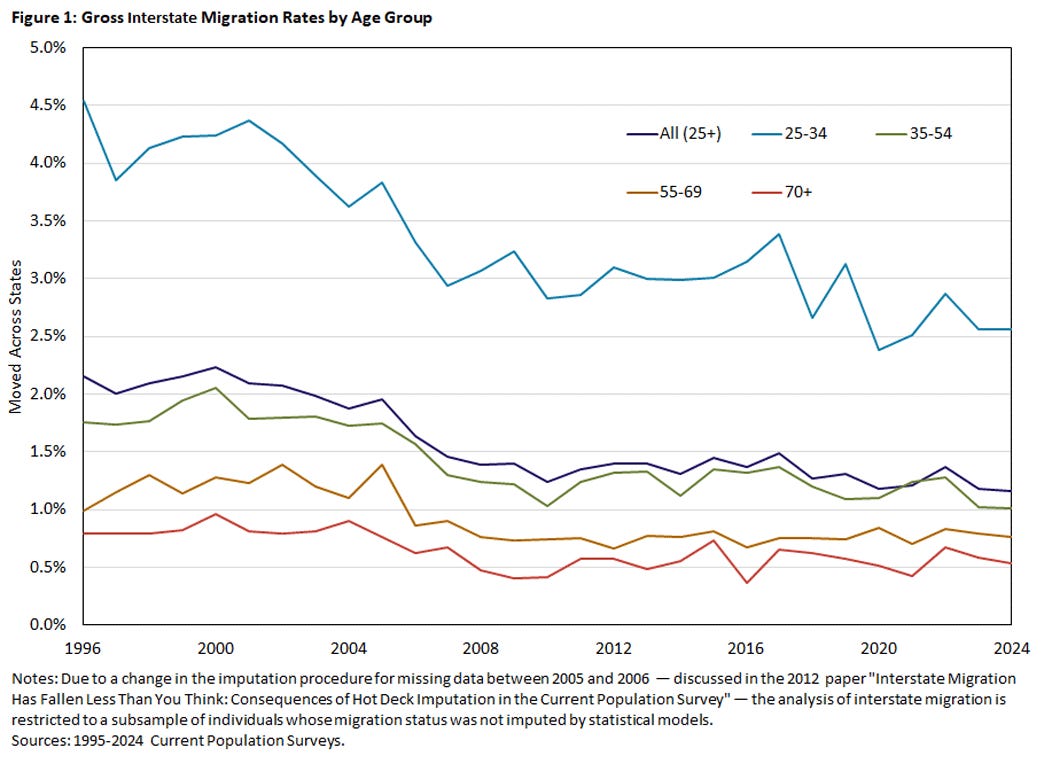

I was totally wrong about this. Americans have been getting less and less likely to move since the mid-1980s:

This effect is mainly driven by young people:

These days, “the typical adult lives only 18 miles from his or her mother“.

4. CULTURE IS STAGNATING

Creativity is just deviance put to good use. It, too, seems to be decreasing.

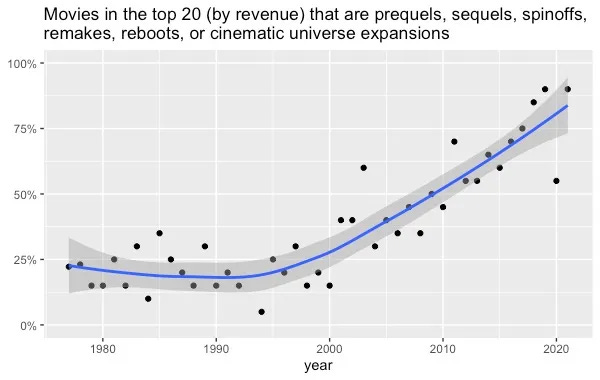

A few years ago, I analyzed a bunch of data and found that all popular forms of art had become “oligopolies”: fewer and fewer of the artists and franchises own more and more of the market. Before 2000, for instance, only about 25% of top-grossing movies were prequels, sequels, spinoffs, etc. Now it’s 75%.

The story is the same in TV, music, video games, and books—all of them have been oligpol-ized. As Ted Gioia points out, we’re still reading comic books about superheroes that were invented in the 1960s, buying tickets to Broadway shows that premiered decades ago, and listening to the same music that our parents and grandparents listened to.

You see less variance even when you look only at the new stuff. According to analyses by The Pudding, popular music today is now more homogenous and has more repetitive lyrics than ever.

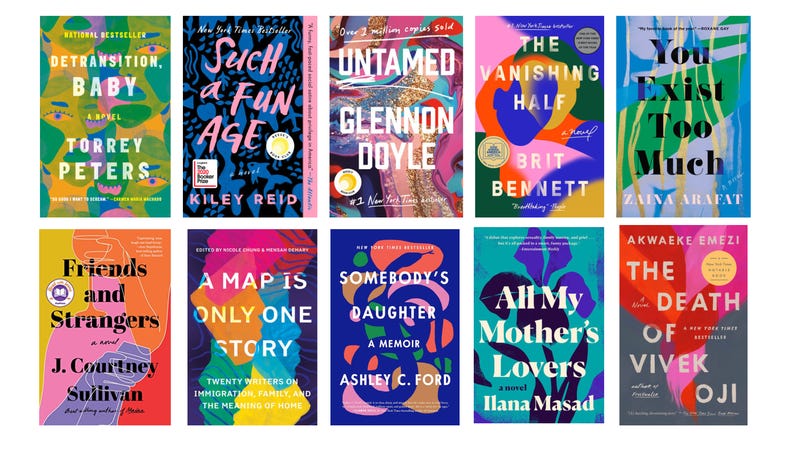

Also, the cover of every novel now looks like this:

But wait, shouldn’t we be drowning in new, groundbreaking art? Every day, people post ~100,000 songs to Spotify and upload 3.7 million videos to YouTube.3 Even accounting for Sturgeon’s Law (“90% of everything is crap”), that should still be more good stuff than anyone could appreciate in a lifetime. And yet professional art critics are complaining that culture has come to a standstill. According to The New York Times Magazine,

We are now almost a quarter of the way through what looks likely to go down in history as the least innovative, least transformative, least pioneering century for culture since the invention of the printing press.

5. THE INTERNET AIN’T INTERESTING ANYMORE

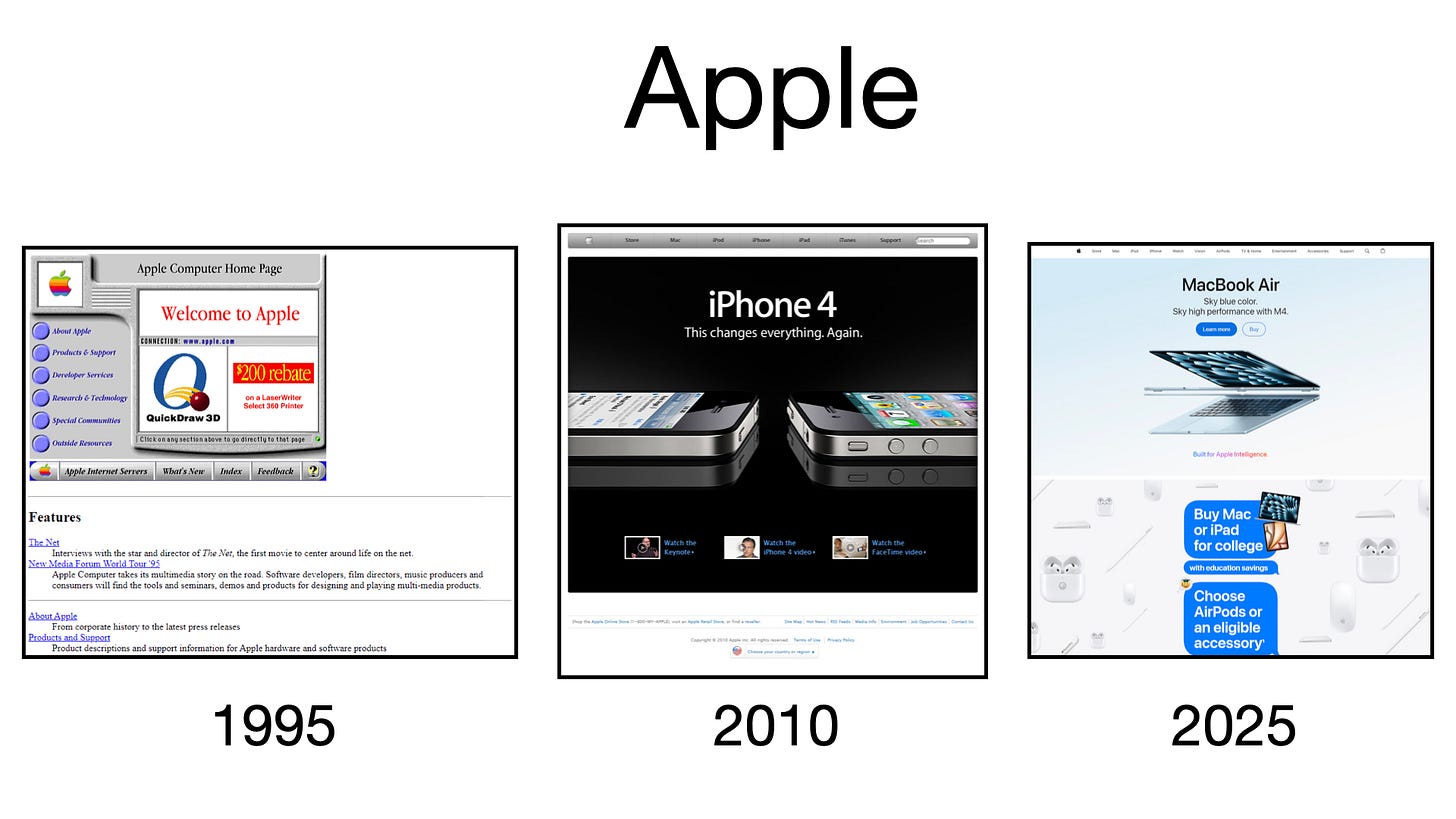

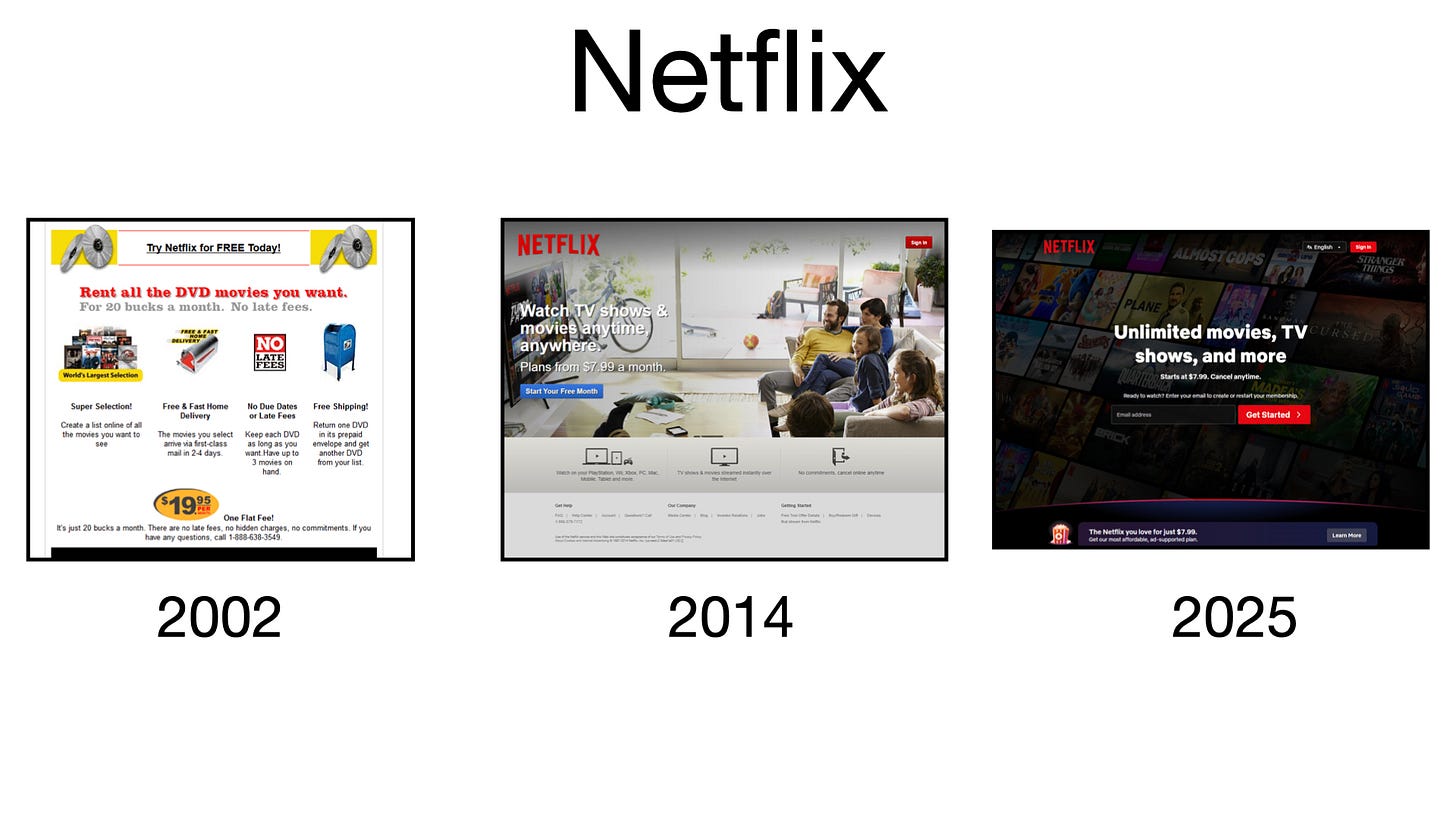

Remember when the internet looked like this?

That era is long gone. Take a stroll through the Web Design Museum and you’ll immediately notice two things:

Every site has converged on the same look: sleek, minimalist design elements with lots of pictures

Website aesthetics changed a lot from the 90s to the 2000s and the 2010s, but haven’t changed much from the 2010s to now

A few examples:

This same kind of homogenization has happened on the parts of the internet that users create themselves. Every MySpace page was a disastrous hodgepodge; every Facebook profile is identical except for the pictures. On TikTok and Instagram, every influencer sounds the same4. On YouTube, every video thumbnail looks like it came out of one single content factory:

No doubt, the internet is still basically a creepy tube that extrudes a new weird thing every day: Trollface, the Momo Challenge, skibidi toilet. But notice that the raw materials for many of these memes is often decades old: superheroes (1930s-1970s), Star Wars (1977), Mario (1981), Pokémon (1996), Spongebob Squarepants (1999), Pepe the Frog (2005), Angry Birds (2009), Minions (2010), Minecraft (2011). Remember ten years ago, when people found a German movie that has a long sequence of Hitler shouting about something, and they started changing the subtitles to make Hitler complain about different things? Well, they’re still doing that.

6. THERE’S LESS TEXTURE IN ARCHITECTURE

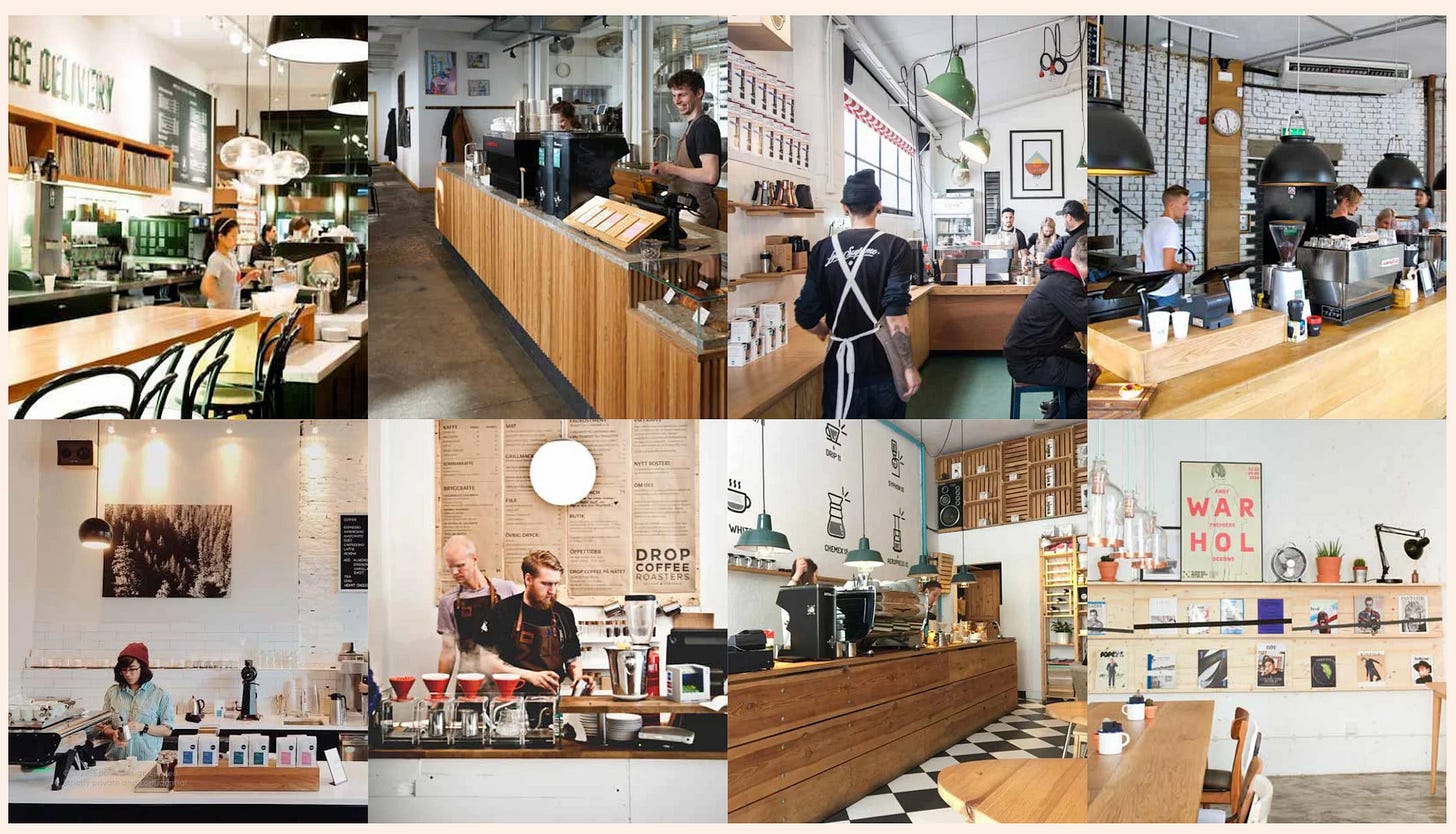

The physical world, too, looks increasingly same-y. As Alex Murrell has documented5, every cafe in the world now has the same bourgeois boho style:

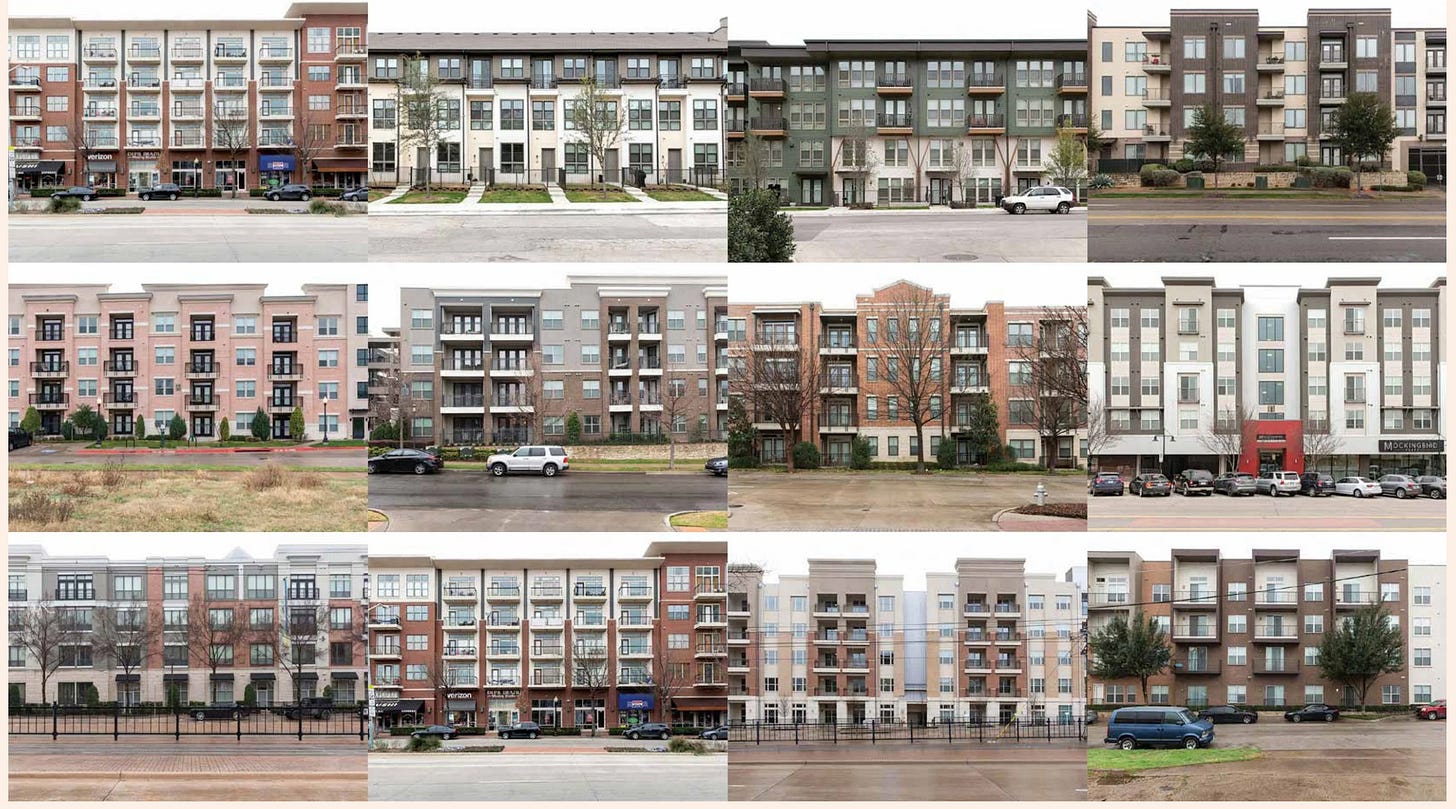

Every new apartment building looks like this:

The journalist Kyle Chayka has documented how every AirBnB now looks the same. And even super-wealthy mega-corporations work out of offices that look like this:

People usually assume that we don’t make interesting, ornate buildings anymore because it got too expensive to pay a bunch of artisans to carve designs into stone and wood.6 But the researcher Samuel Hughes argues that the supply-side story doesn’t hold up: many of the architectural flourishes that look like they have to be done by hand can, in fact, be done cheaply by machine, often with technology that we’ve had for a while. We’re still capable of making interesting buildings—we just choose not to.

7. BRANDS? MORE LIKE...BLANDS. HEH YEAH, GOT ‘EM

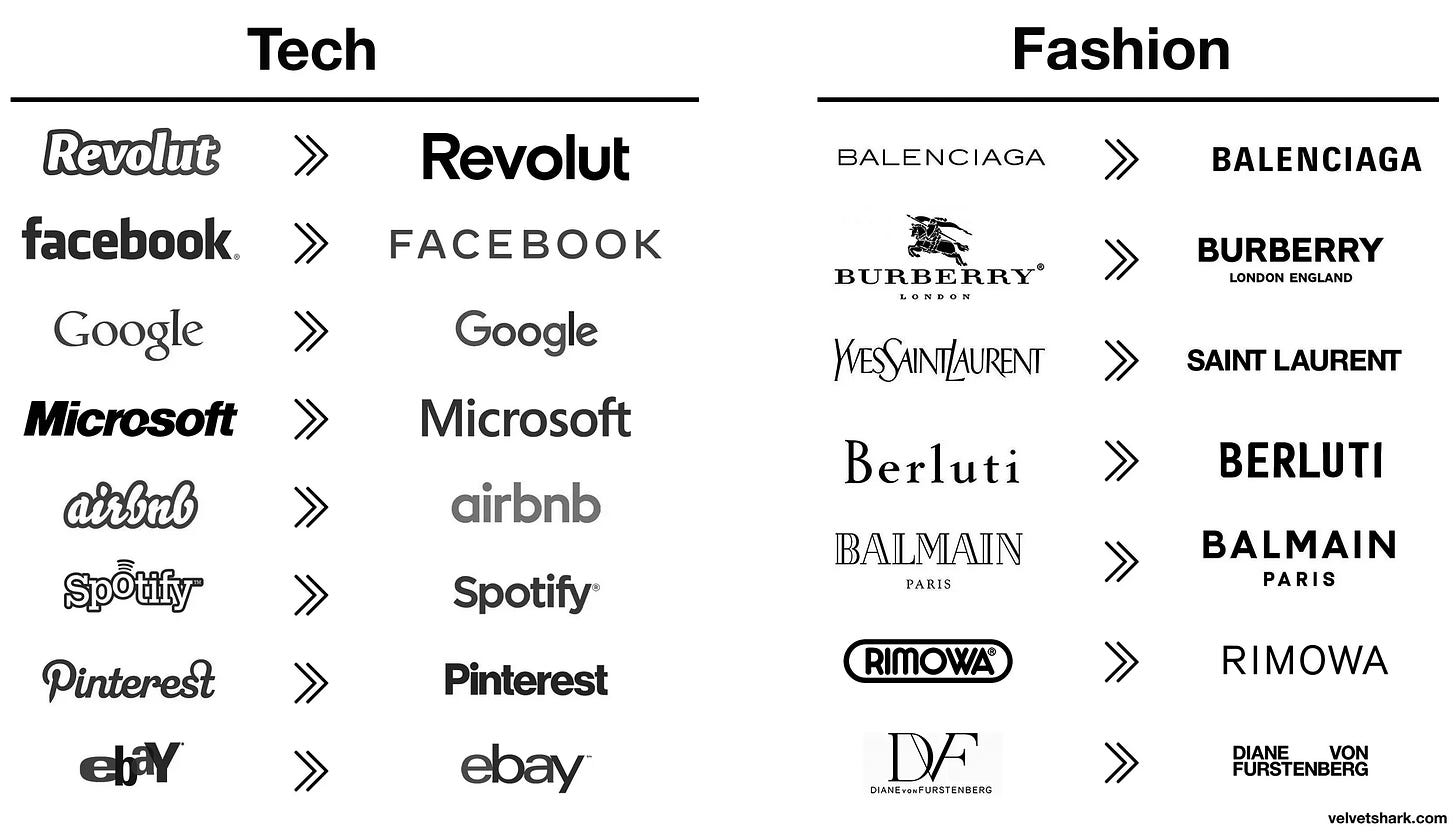

Brands seem to be converging on the same kind of logo: no images, only words written in a sans serif font that kinda looks like Futura.7

An analysis of branded twitter accounts found that they increasingly sound alike:

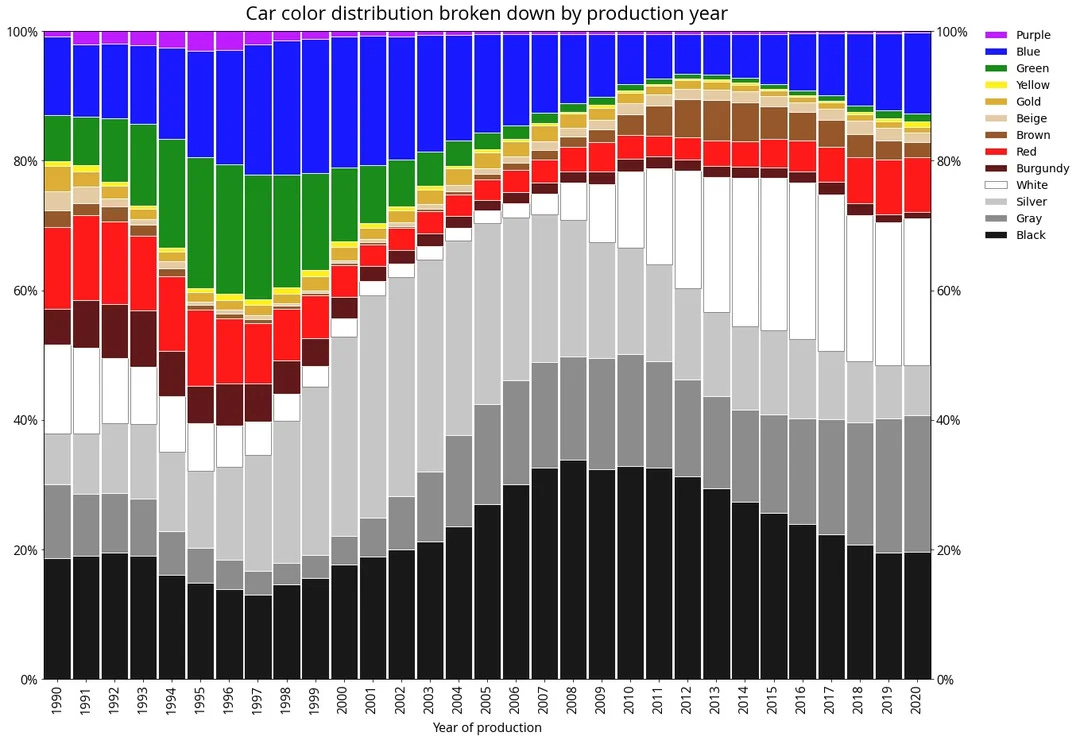

Most cars are now black, silver, gray, or white8:

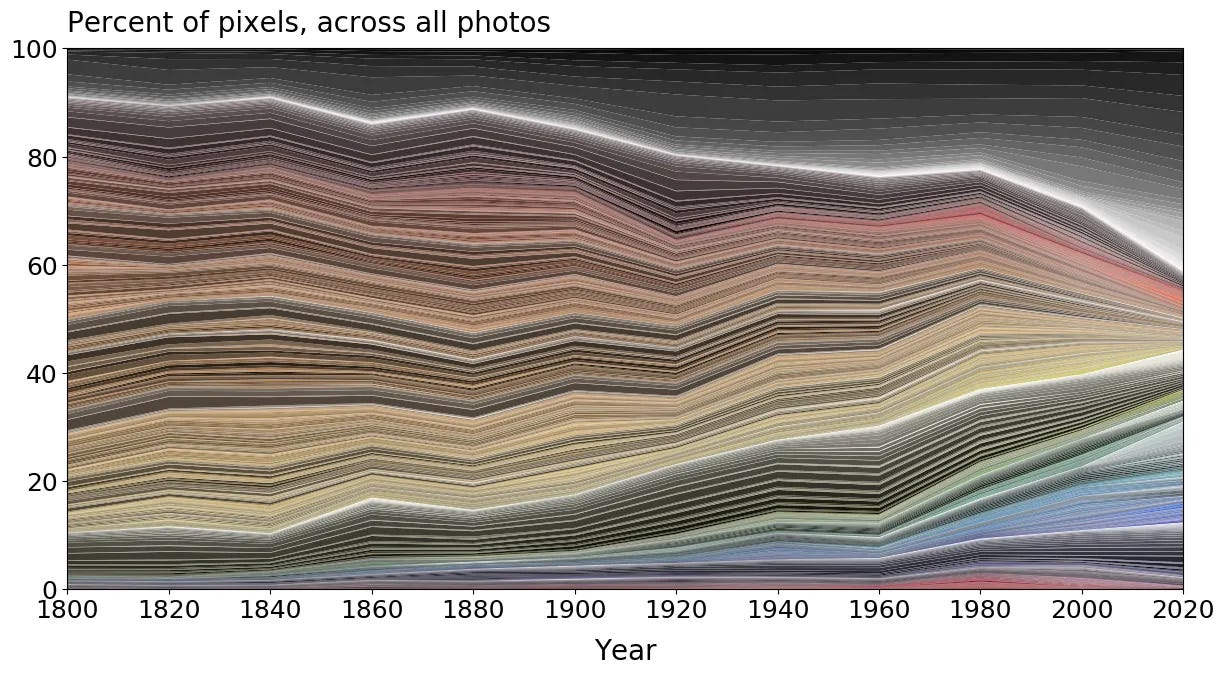

When a British consortium of science museums analyzed the color of their artifacts over time, they found a similar, steady uptick in black, gray, and white:

8. SCIENCE IS STUCK

Science requires deviant thinking. So it’s no wonder that, as we see a decline in deviance everywhere else, we’re also seeing a decline in the rate of scientific progress. New ideas are less and less likely to displace old ideas, experts rate newer discoveries as less impressive than older discoveries, and we’re making fewer major innovations per person than we did 50 years ago.

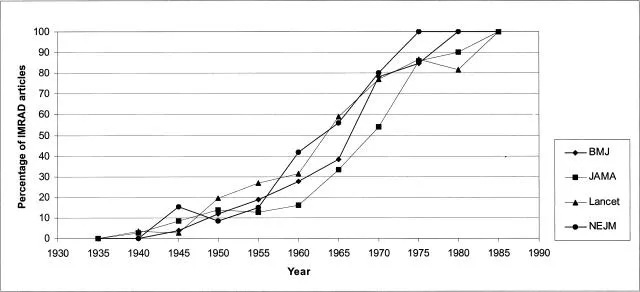

You can spot this scientific bland-ification right away when you read older scientific writing. As Roger’s Bacon (same guy who did the cult analysis) points out, scientific papers used to have style. Now they all sound the same, and they’re all boring. Essentially 100% of articles in medical journals, for instance, now use the same format (introduction, methods, results, and discussion):

This isn’t just an aesthetic shift. Standardizing your writing also standardizes your thinking—I know from firsthand experience that it’s hard to say anything interesting in a scientific paper.

Whenever I read biographies of famous scientists, I notice that a) they’re all pretty weird, and b) I don’t know anyone like them today, at least not in academia. I’ve met some odd people at universities, to be sure, but most of them end up leaving, a phenomenon the biologist Ruxandra Teslo calls “the flight of the Weird Nerd from academia”. The people who remain may be super smart, but they’re unlikely to rock the boat.

9. THESE COMPLAINTS ARE NEW

Whenever you notice some trend in society, especially a gloomy one, you should ask yourself: “Did previous generations complain about the exact same things?” If the answer is yes, you might have discovered an aspect of human psychology, rather than an aspect of human culture.

I’ve spent a long time studying people’s complaints from the past, and while I’ve seen plenty of gripes about how culture has become stupid, I haven’t seen many people complaining that it’s become stagnant.9 In fact, you can find lots of people in the past worrying that there’s too much new stuff. As Derek Thompson relates, one hundred years ago, people were having nervous breakdowns about the pace of technological change. They were rioting at Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and decrying the new approaches of artists like Kandinsky and Picasso. In 1965, Susan Sontag wrote that new forms of art “succeed one another so rapidly as to seem to give their audiences no breathing space to prepare”. Is there anyone who feels that way now?

Likewise, previous generations were very upset about all the moral boundaries that people were breaking, i.e.:

In olden days, a glimpse of stocking

Was looked on as something shocking

But now, God knows

Anything goes

-Cole Porter, 1934

Back then, as far as I can tell, nobody was encouraging young Americans to party more. Now they do. So as far as I can tell, the decline of deviance is not just a perennial complaint. People worrying about their culture being dominated by old stuff—that’s new.

COUNTERPOINT: AM I WRONG?

That’s the evidence for a decline in deviance. Let’s see the best evidence against.

As I’ve been collecting data for this post over the past 18 months or so, I’ve been trying to counteract my confirmation bias by keeping an eye out for opposing trends. I haven’t found many—so maybe that’s my bias at work—but here they are.

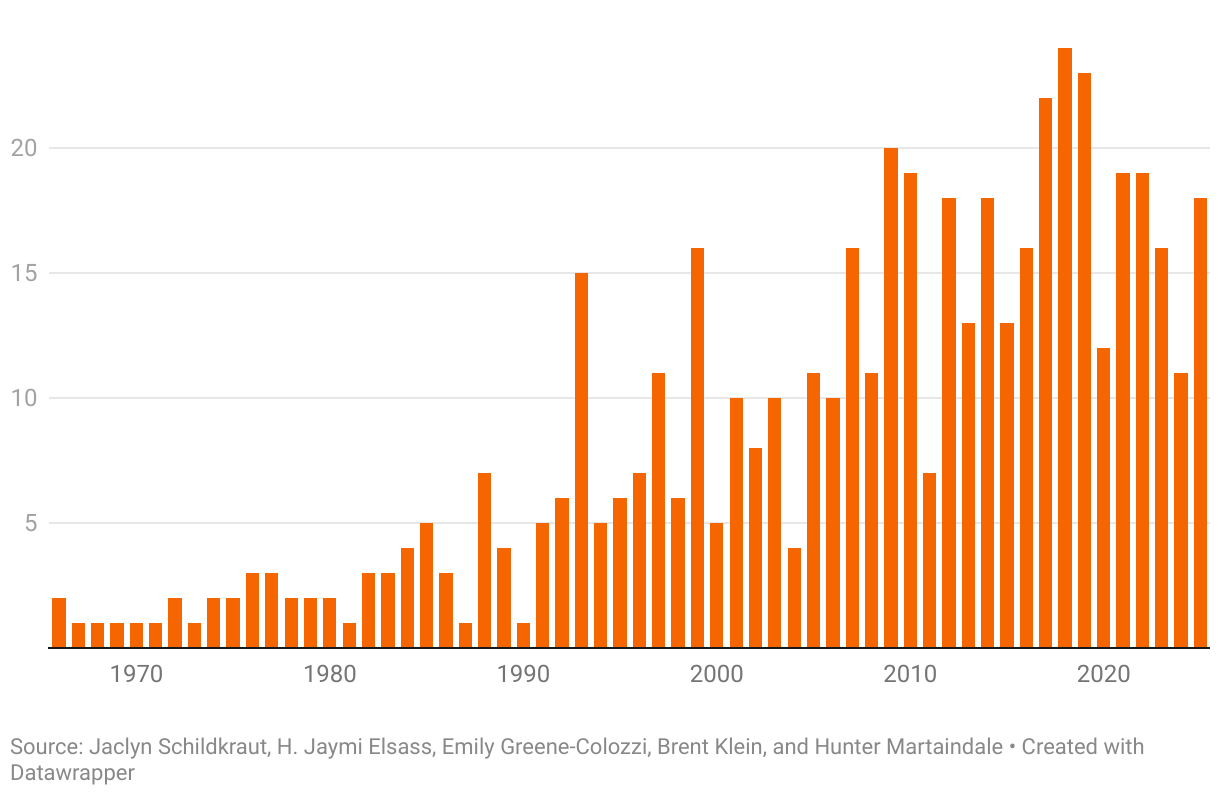

First, unlike other forms of violence, mass shootings have become more common since the 90s (although notice the Y-axis, we’re talking about an extremely small subset of all crime):

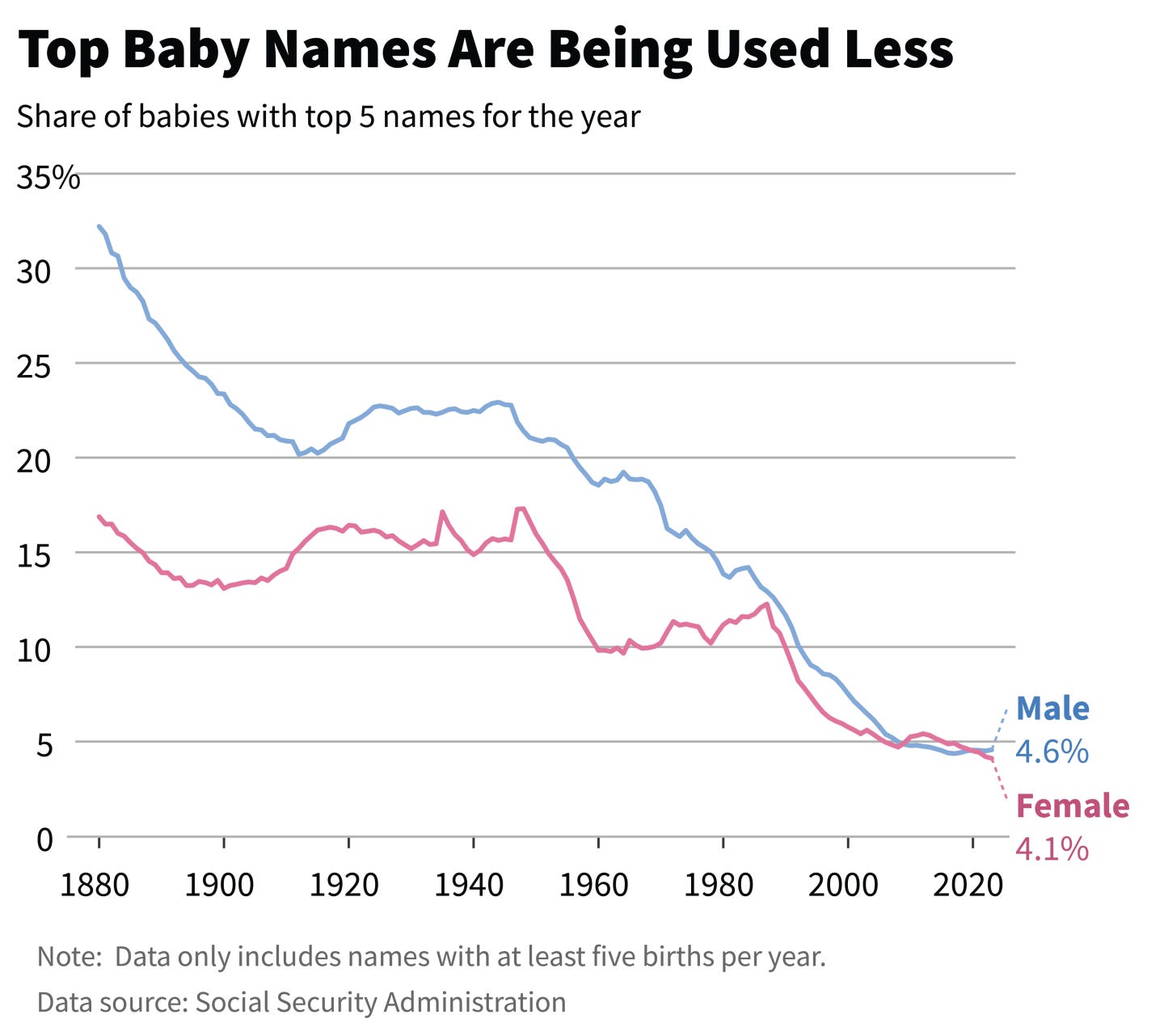

Baby names have gotten a lot more unique:

And when you look at timelines of fashion, you certainly see a lot more change from the 1960s to the 2010s than you do from the 1860s to 1910s:

That at least hints the decline of deviance isn’t a monotonic, centuries-long trend. And indeed, lots of the data we have suggest that things started getting more homogenous somewhere between the 1980s and 2000s.

There are a few people who disagree at least with parts of the cultural stagnation hypothesis. Literature Substacker Henry Oliver reports that “literature is booming”, and music Substacker Chris Dalla Riva is skeptical about stagnation in his industry. The internet ethnographer Katherine Dee argues10 that the most interesting art is happening in domains we don’t yet consider “art”, like social media personalities, TikTok sketch comedy, and Pinterest mood boards. I’m sure there’s some truth to all of this, but I’m also pretty sure it’s not enough to cancel out the massive trends we see everywhere else.

Maybe I’m missing all the new and exciting things because I’m just not cool and plugged in enough? After all, I’ll be the first to tell you there’s a lot of writing on Substack (and the blogosphere more generally) that’s very good and very idiosyncratic—just look at the winners of my blog competitions this year and last year. But I only know about that stuff because I read tons of blogs. If I was as deep into YouTube or podcasts, maybe I’d see the same thing there too, and maybe I’d change my tune.

Anyway, I know that it’s easy to perceive a trend when there isn’t any (see: The Illusion of Moral Decline, You’re Probably Wrong About How Things Have Changed). There’s no way of randomly sampling all of society and objectively measuring its deviance over time. The data we don’t have might contradict the data we do have. But it would have to be a lot of data, and it would all have to point in the opposite direction.

It really does seem like we’re experiencing a decline of deviance, so what’s driving it? Any major social trend is going to have lots of causes, but I think one in particular deserves most of the credit and the blame:

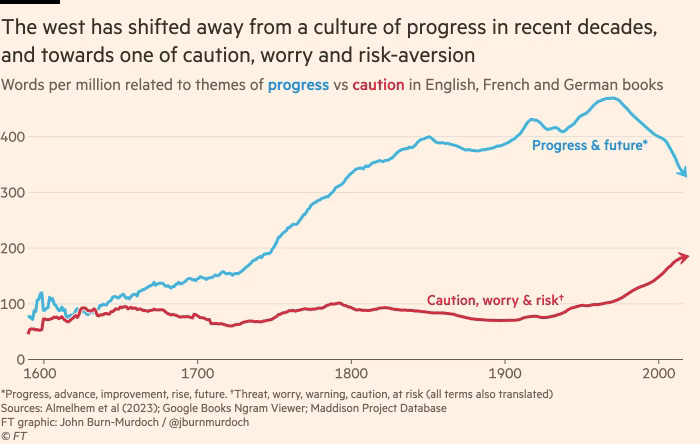

WE CARE MORE ABOUT BEING ALIVE

Life is worth more now. Not morally, but literally. This fact alone can, I think, go a long way toward explaining why our weirdness is waning.

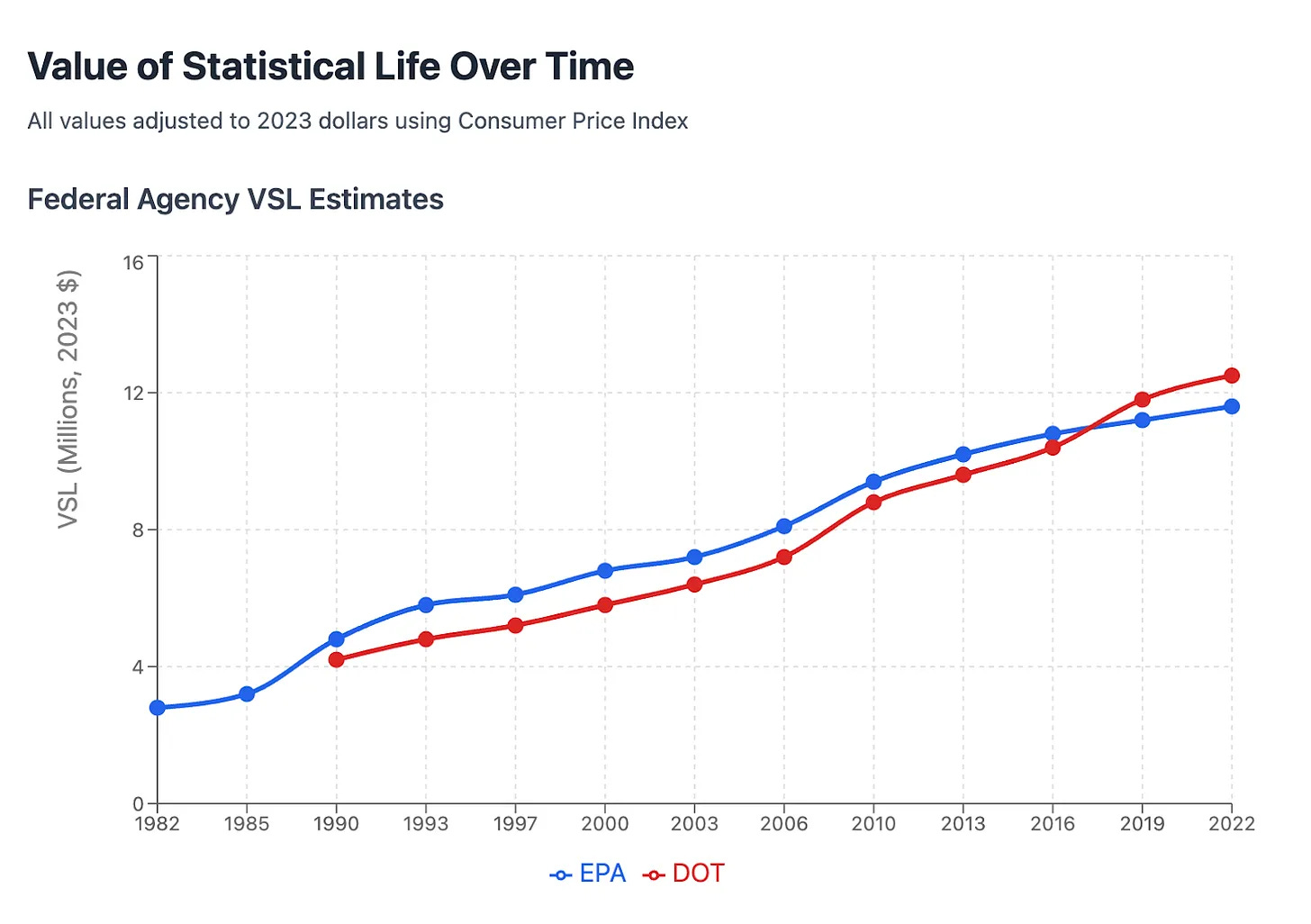

When federal agencies do cost-benefit analyses, they have to figure out how much a human life is worth. (Otherwise, how do you know if it’s worth building, say, a new interstate that will help millions get to work on time but might cause some excess deaths due to air pollution?) They do this by asking people how much they would be willing to pay to reduce their risk of dying, which they then use to calculate the “value of a statistical life”. According to an analysis by the Substacker Linch, those statistical lives have gotten a lot more valuable over time:

There are, I suspect, two reasons we hold onto life more dearly now. First: we’re richer. Generations of economic development have put more cash in people’s pockets, and that makes them more willing to pay to de-risk their lives—both because they can afford it, and because the life they’re insuring is going to be more pleasant. But as Linch points out, the value of a statistical life has increased faster than GDP, so that can’t be the whole story.

Second: life is a lot less dangerous than it used to be. If you have a nontrivial risk of dying from polio, smallpox, snake bites, tainted water, raids from marauding bandits, literally slipping on a banana peel, and a million other things, would you really bother to wear your seatbelt? Once all those other dangers go away, though, doing 80mph in your Kia Sorento might suddenly become the riskiest part of your day, and you might consider buckling up for the occasion.

Our super-safe environments may fundamentally shift our psychology. When you’re born into a land of milk and honey, it makes sense to adopt what ecologists refer to as a “slow life history strategy”—instead of driving drunk and having unprotected sex, you go to Pilates and worry about your 401(k). People who are playing life on slow mode care a lot more about whether their lives end, and they care a lot more about whether their lives get ruined. Everything’s gotta last: your joints, your skin, and most importantly, your reputation. That makes it way less enticing to screw around, lest you screw up the rest of your time on Earth.

(“What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” Make sure I stand up from my desk chair every 20-30 minutes!)

I think about it this way: both of my grandfathers died in their 60s, which was basically on track with their life expectancy the year they were born. I’m sure they hoped to live much longer than that, but they knew they might not make it to their first Social Security check. Imagine how you differently you might live if you thought you were going to die at 65 rather than 95. And those 65 years weren’t easy, especially at the beginning: they were born during the Depression, and one of them grew up without electricity or indoor plumbing.

Plus, both of my grandpas were drafted to fight in the Korean War, which couldn’t have surprised them much—the same thing had happened to their parents’ generation in the 1940s and their grandparents’ generation in the 1910s. When you can reasonably expect your government to ship you off to the other side of the world to shoot people and be shot at in return, you just can’t be so precious about your life.11

My life is nothing like theirs was. Nobody has ever asked me to shoot anybody. I’ve got a big-screen TV. I could get sushi delivered to my house in 30 minutes. The Social Security Administration thinks I might make it to 80. Why would I risk all this? The things my grandparents did casually—smoking, hitching a ride in the back of a pickup truck, postponing medical treatment until absolutely necessary—all of those feel unthinkable to me now.12 I have a miniature heart attack just looking at the kinds of playgrounds they had back then:

I know life doesn’t feel particularly easy, safe, or comfortable. What about climate change, nuclear war, authoritarianism, income inequality, etc.? Dangers and disadvantages still abound, no doubt. But look, 100 years ago, you could die from a splinter. We just don’t live in that world anymore, and some part of us picks that up and behaves accordingly.

In fact, adopting a slow life strategy doesn’t have to be a conscious act, and probably isn’t. Like most mental operations, it works better if you can’t consciously muck it up. It operates in the background, nudging each decision toward the safer option. Those choices compound over time, constraining the trajectory of your life like bumpers on a bowling lane. Eventually this cycle becomes self-reinforcing, because divergent thinking comes from divergent living, and vice versa.13

This is, I think, how we end up in our very normie world. You start out following the rules, then you never stop, then you forget that it’s possible to break the rules in the first place. Most rule-breaking is bad, but some of it is necessary. We seem to have lost both kinds at the same time.14

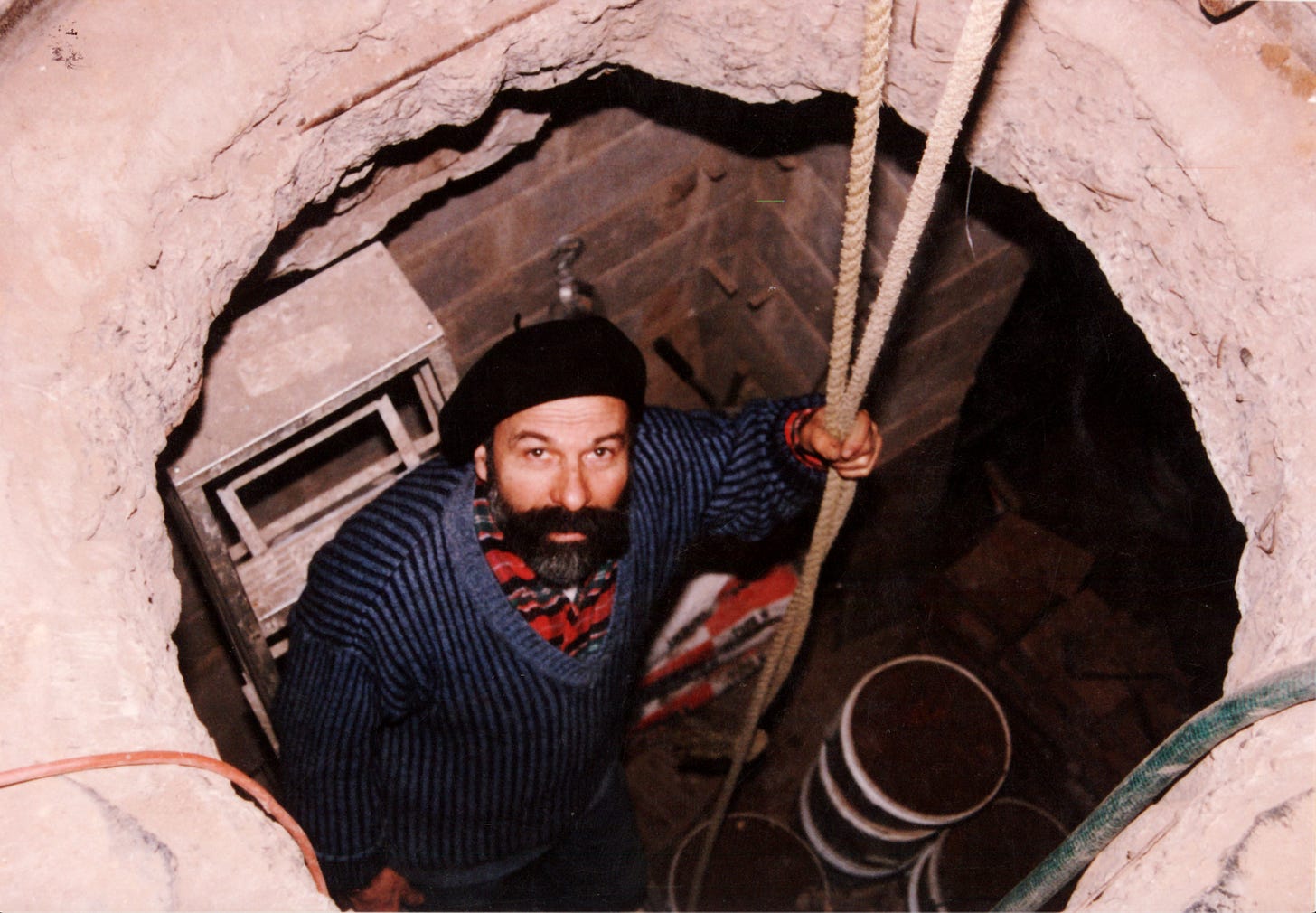

THE STATUE OF LIMITATIONS

The sculptor Arturo di Modica ran away from his home in Sicily to go study art in Florence. He later immigrated to the US, working as a mechanic and a hospital technician to support himself while he did his art. Eventually he saved up enough to buy a dilapidated building in lower Manhattan, which he tore it down so he could illegally build his own studio—including two sub-basements—by hand, becoming an underground artist in the literal sense. He refused to work with an art dealer until 2012, when he was in his 70s. His most famous work, the Charging Bull statue that now lives on Wall Street, was deposited there without permission or payment; it was originally impounded before public outcry caused the city to put it back. Di Modica didn’t mean it as an avatar of capitalism—the stock market had tanked in 1987, and he intended the bull to symbolize resilience and self-reliance:

My point was to show people that if you want to do something in a moment things are very bad, you can do it. You can do it by yourself. My point was that you must be strong.

Meanwhile, “Fearless Girl”, the statue of a girl standing defiantly with her hands on her hips that was installed in front of the bull in 2017, was commissioned by an investment company to promote a new index fund.

Who would live di Modica’s life now? Every step was inadvisable: don’t run away from home, don’t study art, definitely don’t study sculpture, don’t dig your own basement, don’t dump your art on the street! Even if someone was crazy enough to pull a di Modica today, who could? The art school would force you to return home to your parents, the real estate would be unaffordable, the city would shut you down.

The decline of deviance is mainly a good thing. Our lives have gotten longer, safer, healthier, and richer. But the rise of mass prosperity and disappearance of everyday dangers has also made trivial risks seem terrifying. So as we tame every frontier of human life, we have to find a way to keep the good kinds of weirdness alive. We need new institutions, new eddies and corners and tucked-away spaces where strange things can grow.

All of this is within our power, but we must decide to do it. For the first time in history, weirdness is a choice. And it’s a hard one, because we have more to lose than ever. If we want a more interesting future, if we want art that excites us and science that enlightens us, then we’ll have to tolerate a few illegal holes in the basement, and somebody will have to be brave enough to climb down into them.

I’d love to read a version of Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone specifically about the death of cults. Drawing Pentagrams Alone?

Whenever I tell people about the cult deficit, they offer two counterarguments. First: “Isn’t SoulCycle a cult? Isn’t Taylor Swift fandom a cult? Aren’t, like, Lububus a cult?” I think this is an example of prevalence-induced concept change: now that there are fewer cults, we’re applying the “cult” label to more and more things that are less and less cult-y. If your spin class required you to sell all your possessions, leave your family behind, and get married to the instructor, that would be a cult.

Second: “Aren’t conspiracy theories way more popular now? Maybe people are satisfying all of their cult urges from the comforts of their own home, kinda like how people started going to church on Zoom during the pandemic.” It’s a reasonable hypothesis, but the evidence speaks against it. A team of researchers tracked 37 conspiracy beliefs over time, and found no change in the percentage of people who believe them. Nor did they find any increase or decrease in the number of people who endorse domain-general tinfoil-hat thinking, like “Much of our lives are being controlled by plots hatched in secret places”. It seems that hardcore cultists have become an endangered species, while more pedestrian conspiracy theorists are merely as prevalent as they ever were.

There is some skepticism about the Spotify numbers, and I’m sure the YouTube numbers are dubious as well—a big chunk of that content has to be spam, duplicates, etc. But reduce those amounts even by 90% and you still have an impossible amount of songs and videos.

According to Adam Aleksic, the Instagram accent is what you end up with when you optimize your speaking for attracting and holding people’s attention. For more insights like that one, check out his new book.

Thanks to Brian Klaas’s article The Age of the Surefire Mediocre for these and other examples.

Or maybe the conspiracy theorists are right and it’s because some kind of apocalypse wiped out our architectural knowledge and the elites are keeping it hushed up.

Cracker Barrel tried to do the same thing recently and was hounded so hard on the internet that they brought their old logo back.

Note that this data comes from Poland, but if you look up images of American parking lots in previous decades vs. today, you’ll find the same thing.

For instance, T.S. Eliot, 1949:

We can assert with some confidence that our own period is one of decline; that the standards of culture are lower than they were fifty years ago; and that the evidences of this decline are visible in every department of human activity.

Dee’s original article is now paywalled, so I’m linking to a summary of her argument.

Almost all the data I’ve shown you is from the US, so I’m interested to hear what’s going on in other parts of the world. My prediction is that development at first causes a spike in idiosyncrasy as people gain more ways to express themselves—for example, all cars are going to look the same when the only one people can afford is a Model T, and then things get more interesting when more competitors emerge. But as the costs of being weird increase, you’ll eventually see a decline in deviance. That’s my guess, anyway.

Fast life strategies are still possible today, but they’re rarer. Once, in high school, I was over at a friend’s house and his mom lit a cigarette in the living room. I must have looked shocked, because she shrugged at me and said, “If the cigarettes don’t kill me, something else will.” I could at least understand where she was coming from: her husband had died in a car accident before he even turned 50. When you feel like your ticket could get punched at any time, why not enjoy yourself?

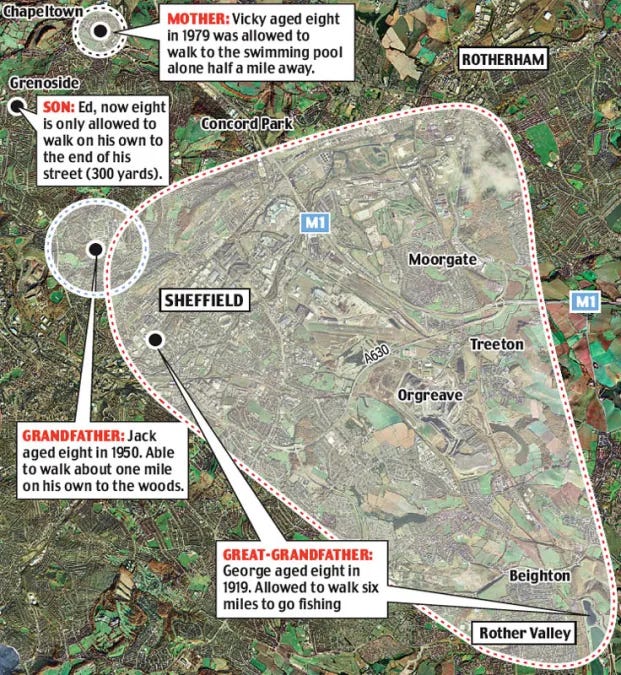

Perhaps that’s also why we’ve become so concerned about the safety of our children, when previous generations were much more laissez-faire. This map traces how the changes in a single family, but the pattern seems broadly true:

There’s a paradox here: shouldn’t safer, wealthier lives make us more courageous? Like, can’t you afford to take more risks when you have more money in the bank?

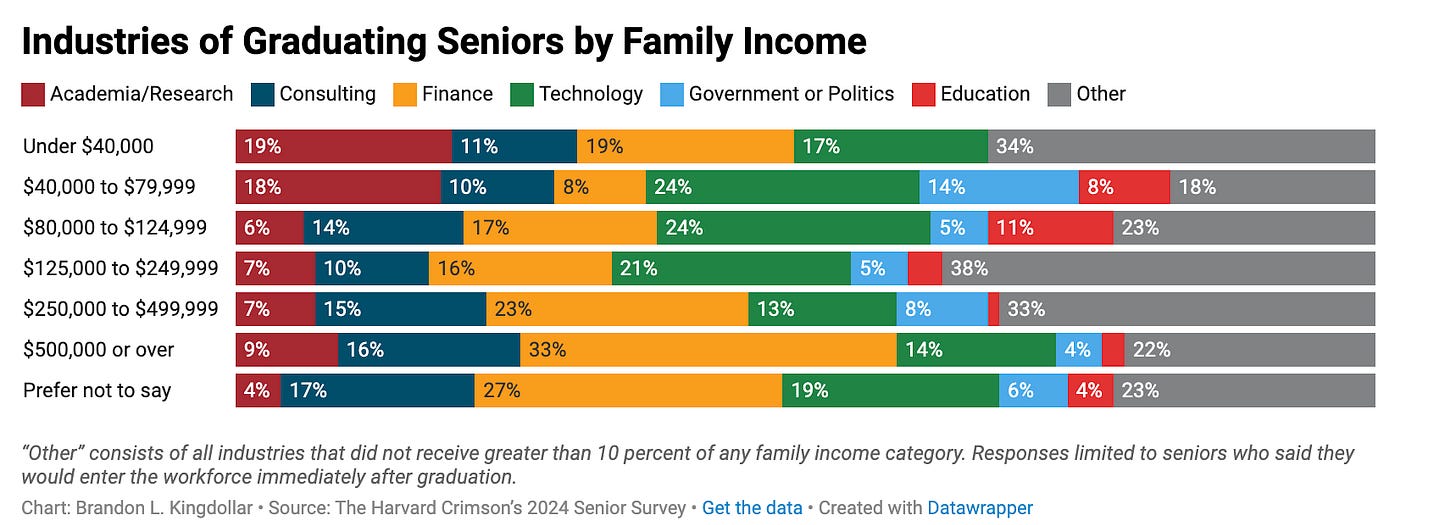

Yes, but you won’t want to. I saw this happen in real time when I was a resident advisor: getting an elite degree ought to increase a student’s options, but instead it makes them too afraid to choose all but a few of those options. Fifty percent of Harvard graduates go to work in finance, tech, and consulting. Most of them choose those careers not because they love making PowerPoints or squeezing an extra three cents of profit out of every Uber ride, but because those jobs are safe, lucrative, and prestigious—working at McKinsey means you won’t have to be embarrassed when you return for your five-year reunion. All of these kids dreamed of what they would gain by going to an Ivy League school; none of them realized it would give them something to lose.

In fact, the richest students are the most likely to pick the safest careers:

Also c’mon this chart is literally made by someone named Kingdollar.

This post inspired me to start smoking

This is what happens when we as a society center our education and work around the core values of productivity and performance, rather than coherence and vitality. If we taught humans how to "know thyself" and then how to be true to thine own self (have integrity), we'd have more sovereign humans giving expression and taking action as only they can. Thus, a wider field of possibilities and opportunity for new connections to be made between all our parts, which is what drives innovation.

Love that I'm finding more and more people exploring the harm in overly-patterned ways of being.