You can't be too happy, literally

OR: there's an air conditioner in your head

Over time, people tend to stay at about the same level of happiness, pretty much no matter what. This is extremely weird.

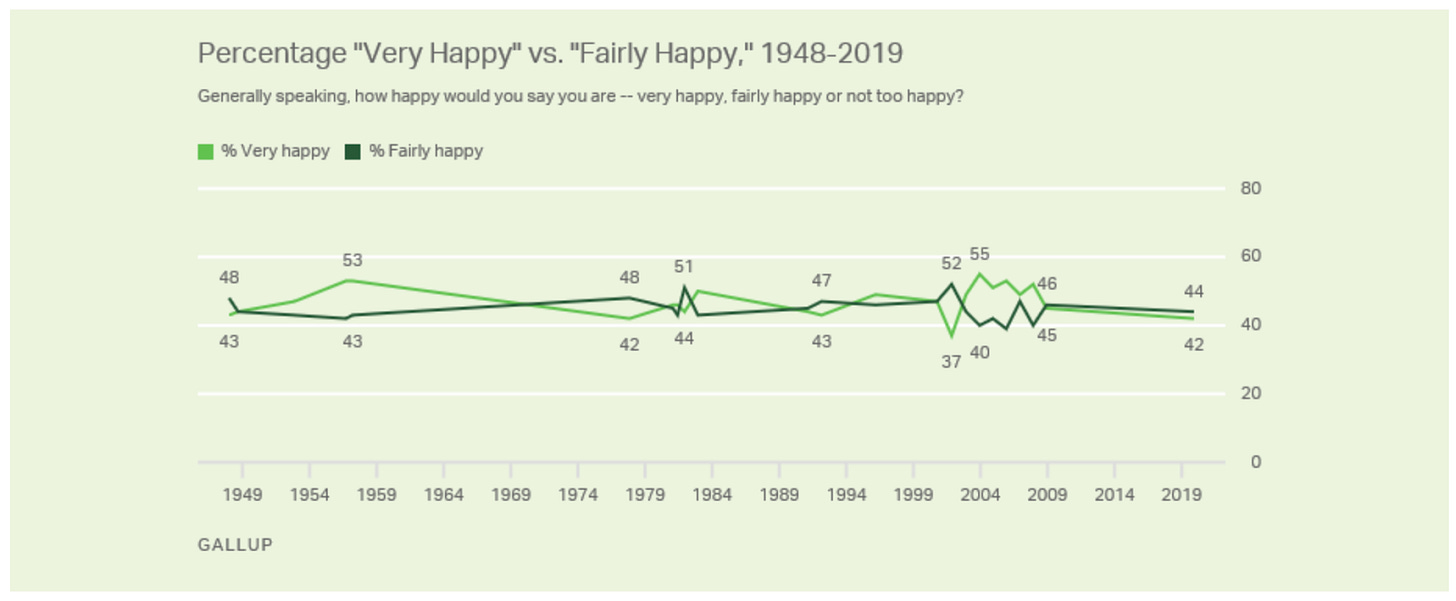

Just look at this:

In social science, that’s pretty much as flat as a line can get. All of the dramatic events of the past 70 years, both good and bad—the Korean War, the Civil Rights Movement, the moon landing, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, stagflation, Watergate, the fall of the Soviet Union, the Gulf War, 9/11, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, a dramatic increase and then decrease in violent crime, the internet, booms and busts of all kinds—none of them mattered, at least in terms of the number of smiles on American faces.

Here’s another way to think about it: in 1948, about 20-30% of American households didn’t have a refrigerator, a flush toilet, or even running water. Zero percent of households had a clothes dryer, air conditioning, or a microwave, because they hadn’t been invented yet. We went from pooping in outhouses to pooping in climate-controlled bathrooms while machines do our laundry and cook our food, and our response was a collective “whatever!”

But maybe we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. The graph above collapses across “Very happy” and “Fairly happy”. Maybe there’s lots of movement between the two?

Nope:

You get the same thing when you ask about “life satisfaction” rather than “happiness”:

And you get the same thing all over the world, with a few notable exceptions:

The data below doesn’t go back as far, but it shows that you still get the same flat lines even when you use a 0-10 scale, where it would be easier to see things moving around:

Most places are stable, a few places are getting slightly happier over time, and a few are slipping toward misery. The handful of countries that have recently gotten sadder are places like Egypt, Venezuela, and Syria, which have suffered from military coups, economic collapse, and civil war, respectively. When there are tanks in the streets, people very reasonably say, “I’m not thrilled about this!” Outside of those extremes, however, people’s happiness doesn’t seem to budge much.

Researchers get the same results when they follow the same people for a long time. They're happier on some days and sadder on other days, but they don’t get much happier or sadder in the long run. (The people in the study, that is, not the researchers—all researchers get sadder in the long run.) There are a few exceptions, though: marrying your best friend really does make you happier, at least for a while, as does divorcing your worst enemy.

(In fact, in that study, getting divorced led to a longer boost in happiness than getting married. This suggests the key to a happy life is getting married and divorced in 3-5 year cycles.)

Psychologists have certainly noticed this and come up with a few theories for it, like “setpoint theory” and “dynamic equilibrium,” but these are mainly descriptive: they state that it happens, not why it happens. That’s fine, you have to document a thing before you can explain it. But “people adapt to things, which they do through the process of adapting to things,” is not gonna cut it as an explanation.

We do have a reasonable explanation for half of this phenomenon. It’s obviously bad to feel sad all the time, so it makes sense that we have ways to cheer ourselves up. (Otherwise our evolutionary ancestors would have been too busy crying to do all the hunting, gathering, and baby-making that it took to produce us.) You can think of this as the psychological immune system or homeostatic mood—when things get too bad, we do stuff to make them better.

That’s great, but there’s still half a puzzle left here. It makes sense that we adjust to bad things, but why do we also adjust to good things? Why, whenever I get a new iPhone, do I feel like “Woohoo my new iPhone so cool so fast the future is now” and then 24 hours later I’m like “My life is normal, I have always had this phone and it makes me feel nothing”?

I think the answer is that the mind has both a furnace, which is well understood, and an air conditioner, which is not well understood at all.

THE FURNACE AND THE AIR CONDITIONER

I am becoming increasingly convinced that minds are best understood as a big web of control systems, which are feedback loops that compare the way things are to the way they should be and then try to reduce the distance between the two1. You can think of control systems as Goldilocks Machines: they’re meant to keep things just right.

Thermostats are the classic example of control systems. You set your target temperature to, say, 70°F. If it ever gets colder than that, the thermostat turns on the furnace. If it gets hotter than that, the thermostat turns on the air conditioning. As long as the system is working properly and the temperatures don’t get too extreme outside, your house will stay close to 70 degrees.

It would make sense for the mind to have lots of control systems, because there are lots of things we have to keep just right. For instance, you’ll die from starvation if you eat too little, but you’ll die from a burst stomach if you eat too much. Hunger and fullness are the furnace and air conditioner of the nutrition control system—you feel ravenous when you need to eat, and you feel bloated when you need to stop eating. It’s an ingenious system, and it can run almost entirely without conscious control. (Evolution: it works!)

Control systems like that probably govern all of the things humans have to do in moderation to stay alive: sleep, empty the bladder and colon, maintain relationships, seek opportunities, avoid dangers, and so on. All of these systems are trying to keep things in whack, and they have a variety of furnaces and air conditioners to deploy when things get too low or too high, like tiredness when you need more sleep, fear when you need more safety, and loneliness when you need more friends. Every day that you don’t pee your pants, you have a control system to thank.

The hallmark of a control system is stability despite disruption. If the temperature starts dropping outside, your furnace works harder, and your house stays at 70. Similarly, if I come home one day and find that someone has stolen all the food out of my fridge, first I’ll call the police, and then I’ll call Domino’s, because, as my nutrition control system will make abundantly clear, I gotta eat. The longer I go without filling my gut, the harder my hunger system will fight to make me fill it. (That’s why, in starvation experiments, people become obsessed with food.)

Happiness sure seems stable despite disruption. Could it be connected to some kind of control system?

Well, we already know the mind has a furnace for mood—that is, we have ways of making ourselves happier when we feel sad. Your girlfriend dumps you and you call your mom so she can tell you that you’re a beautiful boy and everything’s gonna be okay. You lose your job and you distract yourself by playing 12 straight hours of Starcraft. You get rejected by every architecture school and you suddenly realize you never wanted to be an architect anyway. All of this is sensible and good.

But if the mind only had a furnace, happiness wouldn’t be so stable over time. Like the house without air conditioning, we would be able to cheer ourselves up when we feel blue, but there wouldn't be anything to stop our happiness levels from shooting straight up into the stratosphere.

That doesn’t seem to happen, which means our minds must have more than a furnace. We must also have mental air conditioning—that is, ways of making ourselves sadder.

CONSIDER THE POSSIBILITY THAT YOU COULD DIE ALONE AND UNLOVED

As weird as mental air conditioning might sound, it does seem to exist. As the psychiatrist Scott Alexander points out, people with depression seem to do lots of things that keep them sad, like sitting in a dark room and listening to sad music2. He continues:

Depressed people seem to purposefully seek out the most depressing thoughts they can. They find that, unbidden, they are forced to think about the most humiliating thing they ever did, dwell on their worst failures, consider all the things that could go wrong in the future. They’ll be trying to cook dinner, and their brain will tell them “Consider the possibility that you could die alone and unloved.” Why is their brain so insistent that they spend time considering this possibility? Maybe it’s for the same reason that a feverish person’s brain makes them shiver: it’s trying to maintain an extreme state, and it needs to pull out all the stops.

Even normally-functioning people seem to turn on their mental air conditioning from time to time. For example, this study followed a big group of people over time, bugging them every once in a while to report how happy they felt and what they were doing. People tended to do happiness-inducing things when they were sad, but they also did sadness-inducing things when they were happy. Similarly, people sought out their closest friends and family when they were feeling low (which made them feel better), and they spent time alone or with less intimate acquaintances when they were feeling good (which made them feel worse). This looks a lot like flipping between the furnace and the air conditioning.

But why would mental air conditioning exist at all? I mean, what kind of sicko wants to be sadder? What are you trying to do, start a late-90s alt rock band? Why not smash the A/C, crank the furnace, and let the good times roll?

UBER FOR DOGS

Maybe because it’s bad to be too happy.

If you turn up the happiness dial too high for too long, you end up in what psychologists call mania, a state that feels good but is not good. Manic people often end up in the hospital because they do things like drive at 100mph and go flying off the freeway, or they start claiming to be the second coming of Christ, or they blow all their money on wacko business plans (“It’s Uber, but for dogs!”). Here’s an anecdote from a Reddit thread where people describe their first manic episode:

In one month I blew my entire savings (20k on a house), lost 25lbs, started taking on crazy projects at work, bought a whole new wardrobe, Went on like 100 dates. All came crashing down after somehow traveling to DC and wandering the streets at midnight and getting picked up by the police with no phone and no idea where i was.

Here’s another:

I thought I was a psychic, could write a book, bought crystals, did intense meditation. I basically thought I was gifted, to help others communicate with the other side.

Then, a spirit attached itself to me, from a war ground, and it was a mother awaiting her son. I tried to release her spirit lol, and a snake attacked my third eye. Said spirit now wanted to take My son with her to the other side

I started going down after that, I poured salt outside my home, went to see a psychic, ended up at the emergency tapping my head to get the spirits away from entering my chakras.

Plot twist: Im not religious or spiritual.

I spent money I didn’t have, I became hyper sexual, lack of sleep, lots of cannabis, didn’t eat.

And:

I got enough signatures to run for mayor.

Mania is scary because you can feel great while also ruining your life. When you suggest to a depressed person they should maybe get some help, they often respond, “Yeah, you’re right.” When you say that to a manic person, they respond, “No no no you don’t get it, it’s Uber for dogs.” But both extremes are bad—depressed people can’t get out of bed, but manic people can’t get into bed.

So one purpose of mental A/C could be to prevent your brain from—almost literally—overheating. But maybe it does even more than that.

Some control systems are designed to keep things within a small range around a consistent set point. If you hold your breath, for example, it only takes a few seconds to start feeling like “UM HELLO WE NEED TO BREATHE LIKE RIGHT NOW,” which is probably a signal from some kind of oxygen control system (or “too much CO2” system, or whatever it might be). That makes sense, because lack of oxygen is a fast way to die, so whatever control system is responsible for breathing has to run a tight ship.

Other control systems can have larger ranges, or even varying set points. Unless you are, say, a Zen monk, it’s not actually that useful to have exactly the same mood all the time. I, for one, want to be wild on a dance floor and somber at a funeral. If my psychological thermostat was always set to a precise, unchanging 70 degrees, I’d be super annoying. At the club I’d be like, “Whoa guys, let’s not too excited,” at a funeral I’d be like, “C’mon guys, turn that frown upside down!” Maybe having both a psychological furnace and a psychological air conditioner allows us to adopt the mood most necessary for the situation.

Put this way, the hedonic treadmill—the human tendency to adjust to good things, pretty much no matter how good—is not some tragic mind-bug. (Which is exactly how I’ve talked about it before, oops.) It’s actually a critical piece of psychological software. Without it, lottery winners would die of rapturous euphoria. Newlyweds would melt down just from looking at each other. Disneyland would be riddled with the corpses of people who never got bored enough to eat. If our pleasures only piled up and never dissipated, we wouldn’t be able to modulate our moods to suit our needs, and eventually we’d all end up on the hospital tapping our heads to keep the spirits out of our chakras.

COME ON IN AND WRECK THE PLACE

This is already speculative, and now we’re about to enter DEFCON 2-level speculation3, so just a reminder that I’m not the kind of psychologist who helps people with mental illnesses. I’m the kind of psychologist who thinks up metaphors and puts them on the internet.

But if this metaphor is on the right track, it suggests there are two ways to end up sad: either you have an underactive furnace, or you have an overactive air conditioner. (Some unlucky folks might have both.) We might call these people depressives and neurotics, respectively.

For the neurotic, sadness is a work of art, the result of much practice and dedication. They poke holes in every compliment and second-guess every success. They spoil good moments by worrying about how long those moments will last. They study troubling thoughts with the meticulousness of a Talmudic scholar. When a neurotic ends up in the dumps, it’s because they put themselves there, following every sign that says “DUMPS THIS WAY.” Their sadness is an inside job, the culmination of a sprawling conspiracy against themselves.

At the same time, a pure neurotic doesn’t have much trouble cheering themselves up after a setback. In fact, failure is sometimes a relief, because it gives them something useful to focus on.

For depressives, other the other hand, sadness is effortless. While the neurotic fights to make themselves sad, the depressive simply surrenders to the sadness, lowering the drawbridge and shouting, “Come on in and wreck the place!” Depressives politely refuse every good thought and decline every invitation to a better life. They prefer the company of their failures and tragedies, which they keep in barrels in the basement of their brains; they like to stroll among the casks and taste the contents, appreciating how each one ages into an exquisite poison.

At the same time, if you can hoist the depressive out of the dumps, they have an easier time appreciating pleasure than the neurotic does. They don’t have the same skill for undermining their own success and tainting their own good times—they just don't seek out successes and good times in the first place.

Everybody’s got at least a bit of both, of course, but it sure feels like some people fall more on one side of this spectrum than the other. When I had a skull full of poison, I was all neurotic—making myself sad was my #1 job, and I was employee of the month, every month. In normal times, I can cope with setbacks just fine; it’s success I can’t handle. I’ve known plenty of folks who were the opposite: a win can buoy them for months, but a loss can bury them for a year.

If I can raise the speculation level to DEFCON 1.5 for a second, maybe the reason why we’re not great at treating anxiety and depression is that we don’t have a good sense of the underlying systems that we’re trying to fix. Some sadness might be caused by a system working too hard, and other sadness might be caused by a different system not working hard enough, and both could be happening at the same time. It doesn’t seem likely that one treatment is going to work for each of those situations, but what do I know!

I’M BEGGING YOU, NO MORE GUMMY WORMS

I’ve always wondered, “Why don’t people eat sugar until they die?” Not in the long-term sense of eating too much sugar your whole life and maybe dying earlier. I mean in the very short-term sense of ripping open a bag of the sweet stuff and gulping it down until your stomach pops or your heart stops.

After all, don’t humans love sugar? Aren’t we practically addicted to it? Didn’t we evolve in an environment where access to sugar was extremely limited? Now that we can get unlimited sugar for like $2, why don’t we spend way more time doing that?

I think the answer is that we don’t actually “like” sugar—we like a certain amount of sugar. Have you ever wolfed down a whole bag of gummy worms? An hour later, even the sight of another gummy worm makes you sick. That’s the sugar control system going “NO MORE PLEASE.”

This same logic might apply across the whole mind. It seems obvious—almost axiomatic!—to say that humans “like” to feel good. But maybe we like to feel a certain amount of good. That’s the logic behind control systems (or as biologists might call them, “homeostatic mechanisms”): you need the right amounts of everything, and too much of a good thing is a bad thing.

While I was doing research for this post, I ran across this line in a paper: “individuals are basically oriented to the maximization of positive affect and the minimization of negative affect (e.g., Atkinson, 1957; Epstein, 1980; Freud, 1952; E. T. Higgins, 1997; Schaller & Cialdini, 1990; Taylor, 1991; Zillmann, 1988)”.

Until recently, I would have thought that claim was so obvious that it didn’t even need a citation, let alone six of them. But now it doesn’t seem true at all!

If people just want to feel good all the time, then why do they watch movies about the Holocaust? Why do they go to haunted houses? Why do they pay to get tied up and yelled at and whipped? Why do they ruminate over their past failures and worry about their failures to come? Why is there a popular song called “Gloomy Sunday (The Hungarian Suicide Song)” that has been covered dozens of times? These experiences cause “negative affect,” and yet people seek them out. That’s really weird! Maybe it’s because people are driven to feel bad sometimes, and that’s something a normally functioning mind would do, just not too much.

But now I’m just getting worked up. I better go cool myself down, lest I start collecting signatures to run for mayor.

These ideas were sparked by conversation with SMTM, shortly after we sniffed plates together.

That doesn’t mean people with depression are to blame for making themselves sad, but it does explain why they have such a hard time feeling better.

I looked up the DEFCON levels because I forgot whether higher levels are more DEFCON-y (DEFCON 1 is the worst, turns out), and learned that each level has a cool name to go with it. So DEFCON 2 is “FAST PACE,” which is right below “ROUND HOUSE” and just above “COCKED PISTOL.”

The stable happiness over time is fascinating at the societal level. Maybe moving out of a pure psychological analysis, but what does this say about societal notions of "progress"? If we were just as happy before we had toilets, in what sense can we say the world is getting any better due to technology? Maybe we can say that things that objectively reduce disease and dying are good (because they allow each person to get more time being happy) but is technology that just makes life more convenient or entertaining basically worthless under this model?

While fascinating, I see a major problem with all happiness studies.

Back when I did research and treated patients in the field of pain management, we only had one reliable tool to measure pain - a Likert scale from 1 to 10.

How often, in the beginning, did I hear from patients, after telling them "10" is the worst pain ever, "Oh, Doc, mine is at least 11."

It took me a few weeks to find a way to get past this: "Ok, how about on a scale of 1 to 100?" "Oh, well then, maybe 70?"

I always managed to resist the urge to say, "Right, you mean "7" on a 10 point scale?"

It's even worse with meditation research. As much as we like to think, in our age of technological hubris, we can "measure" the results of meditation with brain waves or other tech aids, actually, the only way to know IF a person is meditating much less how well they're doing, is to ask.

I don't know, if you haven't talked with hundreds of people and started to get a sense of how abysmally poor people are at reporting events in their minds, you may not be as skeptical as I am. My sense is of the millions tested for meditation, probably less than 1% are actually "meditating" most of the time (maintaining a continuous, non judgmental, open awareness, without identifying with the passage thoughts, feelings and sensations)

But like pain, what in the world do people think being "happy" means (assuming they could make distinctions related to eros vs agape or some other kind of categorical system).

Oh, sampling millions of people makes a difference? I don't quite see how, since if your methodology is not valid on a small scale, I don't quite see how a larger scale makes any difference.

having said all that, I suspect your main premise holds, that barring civil war and other traumas, general resigned, bored contentment (ie the researchers' apparent idea of "happiness") probably doesn't change much.