I swear the UFO is coming any minute

Links 'n' updates

This is the quarterly links ‘n’ updates post, a selection of things I’ve been reading and doing for the past few months.

First up, a series of unfortunate events in science:

(1) WHEN WHEN PROPHECY FAILS FAILS

When Prophecy Fails is supposed to be a classic case study of cognitive dissonance: a UFO cult predicts an apocalypse, and when the world doesn’t end, they double down and start proselytizing even harder: “I swear the UFO is coming any minute!”

A new paper finds a different story in the archives of the lead author, Leon Festinger. Up to half of the attendees at cult meetings may have been undercover researchers. One of them became a leader in the cult and encouraged other members to make statements that would look good in the book. After the failed prediction, rather than doubling down, some of the cultists walked back their statements or left altogether.

Between this, the impossible numbers in the original laboratory study of cognitive dissonance, and a recent failure to replicate a basic dissonance effect, things aren’t looking great for the phenomenon.1 But that only makes me believe in it harder!

(2) THE MAN WHO MISTOOK HIS WIFE FOR A HAT AND A LIE FOR THE TRUTH

Another classic sadly struck from the canon of behavioral/brain sciences: the neurologist Oliver Sacks appears to have greatly embellished or even invented his case studies. In a letter to his brother, Sacks described his blockbuster The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat as a book of “fairy tales [...] half-report, half-imagined, half-science, half-fable”.

This is exactly how the Stanford Prison Experiment and the Rosenhan experiment got debunked—someone started rooting around in the archives and found a bunch of damning notes. I’m confused: back in the day, why was everybody meticulously documenting their research malfeasance?

(3) A SMASH HIT

If you ever took PSY 101, you’ve probably heard of this study from 1974. You show people a video of a car crash, and then you ask them to estimate how fast the cars were going, and their answer depends on what verb you use. For example, if you ask “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” people give higher speed estimates than if you ask, “How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” (Emphasis mine). This study has been cited nearly 4,000 times, and its first author became a much sought-after expert witness who testifies about the faultiness of memory.

A blogger named Croissanthology re-ran the study with nearly 10x as many participants (446 vs. 45 in the original). The effect did not replicate. No replication is perfect, but no original study is either. And remember, this kind of effect is supposed to be so robust and generalizable that we can deploy it in court.

I think the underlying point of this research is still correct: memory is reconstructed, not simply recalled, so what we remember is not exactly what we saw. But our memories are not so fragile that a single word can overwrite them. Otherwise, if you ever got pulled over for speeding, you could just be like, “Officer, how fast was I going when my car crawled past you?”

(4) CHOICE UNDERLOAD

In one study from 1995, physicians who were shown multiple treatment options were more likely to recommend no treatment at all. The researchers thought this was a “choice overload” effect, like “ahhh there’s too many choices, so I’ll just choose nothing at all”. In contrast, a new study from 2025 found that when physicians were shown multiple treatment options, they were somewhat more likely to recommend a treatment.

I think “choice overload” is like many effects we discover in psychology: can it happen? Yes. Can the opposite also happen? Also yes. When does it go one way, and when does it go the other? Ahhh you’re showing me too many options I don’t know.

(5) THE TALE OF THE TWO-INCH DOG

Okay, enough dumping on other people’s research. It’s my turn in the hot seat.

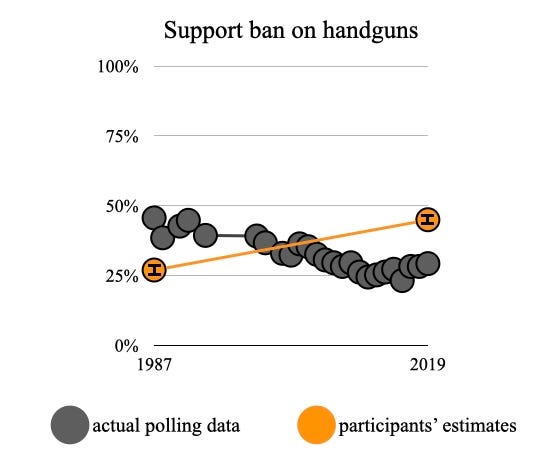

In 2022, my colleague Jason Dana and I published a paper showing that people don’t know how public opinion has changed. Like this:

A new paper by Irina Vartanova, Kimmo Eriksson, and Pontus Strimling reanalyzes our data and finds that actually, people are great at knowing how public opinion has changed.

What gives? We come to different conclusions because we ask different questions. Jason and I ask, “When people estimate change, how far off are they from the right answer?” Vartanova et al. ask, “Are people’s estimates correlated with the right answer?” These approaches seem like they should give you the same results, but they don’t, and I’ll show you why.

Imagine you ask people to estimate the size of a house, a dog, and a stapler. Vartanova’s correlation approach would say: “People know that a house is bigger than a dog, and that a dog is bigger than a stapler. Therefore, people are good at estimating the sizes of things.” Our approach would say: “People think a house is three miles long, a dog is two inches, and a stapler is 1.5 centimeters. Therefore, people are not good at estimating the sizes of things.”

I think our approach is the right one, for two reasons. First, ours is more useful. As the name implies, a correlation can only tell you about the relationships between things. So it can’t tell you whether people are good at estimating the size of a house. It can only tell you whether people think houses are bigger than dogs.

Second, I think our approach is much closer to the way people actually make these judgments in their lives. If I asked you to estimate the size of a house, you wouldn’t spontaneously be like, “Well, it’s bigger than a dog.” You’d just eyeball it. I think people do the same thing with public opinion—they eyeball it based on headlines they see, conversations they have, and vibes they remember. If I asked you, “How have attitudes toward gun control changed?” you wouldn’t be like, “Well, they’ve changed more than attitudes toward gender equality.”2

While these reanalyses don’t shift my opinion, I’m glad people are looking into shifts in opinions at all, and that they found our data interesting enough to dig into.

(6) Let’s cleanse the palate. Here’s Jiggle Kat:

(7) THROWN FOR A LOOP

THE LOOP is a online magazine produced by my friends Slime Mold Time Mold. The newest issue includes:

a study showing that people maybe like orange juice more when you add potassium to it

a pseudonymous piece by me

scientific skepticism of the effectiveness of the Squatty Potty, featuring this photo:

This issue of THE LOOP was assembled at Inkhaven, a blogging residency that is currently open for applications. I visited the first round of this program and was very impressed.

(8) LEARN FROM GWERN

Also at Inkhaven, I interviewed the pseudonymous blogger Gwern about his writing process. Gwern is kind of hard to explain. He’s famous on some parts of the internet for predicting the “scaling hypothesis”—the fact that progress in AI would come from dumping way more data into the models. But he also writes poetry, does self-experiments, and sustains himself on $12,000 a year. He reads 10 hours a day every day, and then occasionally writes for 30 minutes. Here’s what he said when I was like, “Very few people do experiments and post them on the internet. Why do you do it?”

I did it just because it seemed obviously correct and because… Yeah. I mean, it does seem obviously correct.

For more on what I learned by interviewing a bunch of bloggers, see I Know Your Secret.

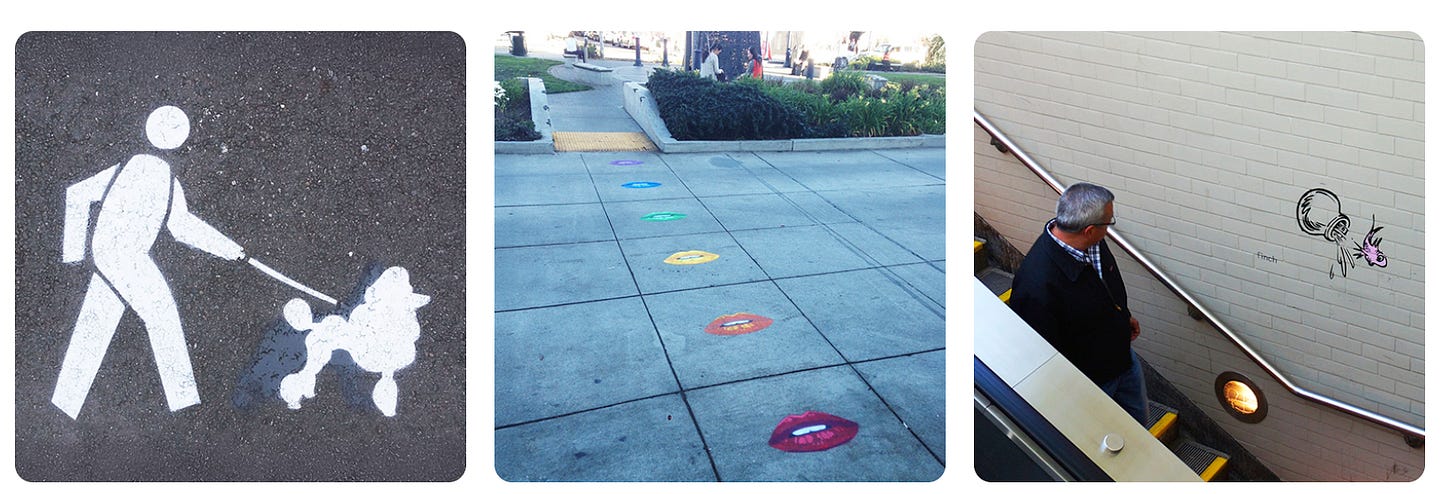

(9) ART NOUVEAU RICHE

I really like this article by the artist known as fnnch: How to Make a Living as an Artist. It’s super practical and clear-headed writing on a subject that is usually more stressed about than thought about. Here’s a challenge: which of these seven images became successful, allowing fnnch to do art full time?

I’ll give the answer at the bottom of the post.

(10) A WEB OF LIES

Anyone who grew up in the pre-internet days probably heard the myth that “you swallow eight spiders every year in your sleep”, and back then, we just had to believe whatever we heard.

Post-internet, anyone can quickly discover that this “fact” was actually a deliberate lie spread by a journalist named Lisa Birgit Holst. Holst included the “eight spiders” myth in a 1993 article in a magazine called PC Insider, using it as an example of exactly the kind of hogwash that spreads easily online.

That is, anyway, what most sources will tell you. But if you dig a little deeper, you’ll discover that the whole story about Lisa Birgit Holst is also made up. “Lisa Birgit Holst” is an anagram of “This is a big troll”; the founder of Snopes claims he came up with it in his younger and wilder days. The true origin of the spiders myth remains unknown.

(11) I’D LIKE TO SPEAK TO A MANAGER 19 TIMES A DAY

In 2015, Reagan National Airport in DC received 8,760 noise complaints; 6,852 of those complaints (78%) came from a single household, meaning the people living there called to complain an average of 19 times a day. This seems to be common both across airports and across complaint systems in general: the majority of gripes usually comes from a few prolific gripers. Some of these systems are legally mandated to investigate every complaint, so this means a handful of psychotic people with telephones—or now, LLMs—can waste millions of dollars. I keep calling to complain about this, but nobody ever does anything about it.

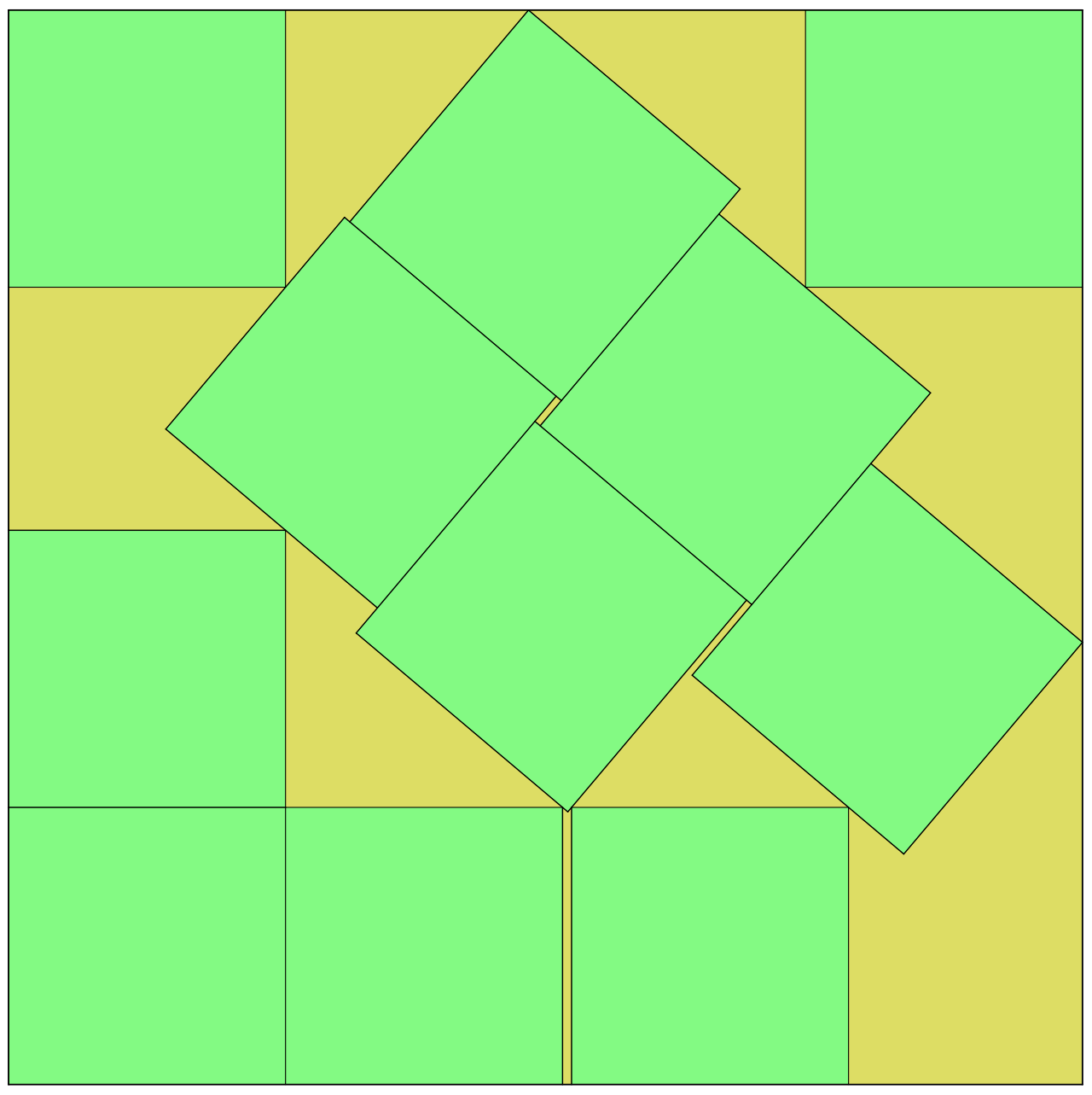

(12) BE THERE OR BE 11 SQUARES

Did you know that this is the most compact known way to pack 11 squares together into a larger square?

Really makes you think about the mindset of whoever made the universe, am I right?

(More here.)

(13) NOW WE’RE COOKING WITH NO GAS

Malmesbury digs up the “world’s saddest cookbook” and finds that it’s…pretty good?

He successfully makes steak and eggs, two things that are supposed to be impossible in the microwave. The only thing you can’t make? Multiple potatoes.

There’s a reason the book is called Microwave Cooking for One and not Microwave Cooking for a Large, Loving Family. […] It’s because microwave cooking becomes exponentially more complicated as you increase the number of guests. […] Baking potatoes in the microwave is an NP-hard problem.

NEWS FROM EXPERIMENTAL HISTORY HQ

I was tickled to see that an actual Christian theologian/data scientist found my post called There Are No Statistics in the Kingdom of God. He mostly agreed with the argument, but he does think statistics will continue to exist in heaven. We shall see!

I was back on Derek Thompson’s “Plain English” podcast talking about the decline of deviance.

I was also on the “What Is a Good Life?” podcast with Mark McCartney talking about the good life.

“Why Aren’t Smart People Happier” won a Sidney Award, recognizing “excellence in nonfiction essays”:

And finally, the answer to the question I posed earlier: the art that made fnnch famous was the honey bear. Go figure!

I know people will be like “there are hundreds of studies that confirm cognitive dissonance”. But if you look at that study that didn’t replicate, it had 10 participants per condition. That’s way too few to detect anything interesting—you need 46 men and 46 women just to demonstrate the fact that men weigh more than women, on average. Many of those other cognitive dissonance studies have similarly tiny samples, so their existence doesn’t put me at ease. Plus, the theorizing here is so squishy that many different patterns of results could arguably confirm or disconfirm the theory: here’s someone arguing that, in fact, the failure to replicate was actually a success.

A reporter tracked down Elliot Aronson, a student of Festinger and a dissonance researcher himself, and posed the following question to him:

I asked him how the theory could be falsified, since any choice a person made could be attributed to dissonance. “It’s hard to disprove anything,” he said.

Very true, on many levels.

There’s one more point where we disagree. Vartanova et al. point out that 70% of estimates are in the right direction—as in, if support for gun control went down, 70% of participants correctly guessed that it went down. The researchers look at that number and go, “That seems pretty good”. We look at the exact same number and go, “That seems pretty bad”. Obviously this is a judgment call, but getting the direction right is such a low bar that we think it’s remarkable so many people don’t clear it. Getting the direction of change wrong is a bit like saying that a dog is bigger than a house.

For those unaware of the classsic:

"average person eats 3 spiders a year" factoid actualy just statistical error. average person eats 0 spiders per year. Spiders Georg, who lives in cave & eats over 10,000 each day, is an outlier adn should not have been counted

Thanks again for bringing joy to the internet.