Surely you can be serious

OR: "You can do whatever you want, as long as you work for a dictator first"

I once saw someone give a talk about a tiny intervention that caused a gigantic effect, something like, “We gave high school seniors a hearty slap on the back and then they scored 500 points higher on the SAT.”1

Everyone in the audience was like, “Hmm, interesting, I wonder if there were any gender effects, etc.”

I wanted to get up and yell: “EITHER THIS IS THE MOST POTENT PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTION EVER, OR THIS STUDY IS TOTAL BULLSHIT.”

If those results are real, we should start a nationwide backslapping campaign immediately. We should be backslapping astronauts before their rocket launches and Olympians before their floor routines. We should be running followup studies to see just how many SAT points we can get—does a second slap get you another 500? Or just another 250? Can you slap someone raw and turn them into a genius?

Or—much more likely—the results are not real, and we should either be a) helping this person understand where they screwed up in their methods and data analysis, or b) kicking them out for fraud.

Those are the options. Asking a bunch of softball questions (“Which result was your favorite?”) is not a reasonable response. That’s like watching someone pull a rabbit out of a hat actually for real, not a magic trick, and then asking them, “What’s the rabbit’s name?”

LOGAN ROY, PSYCHOLOGIST

There’s a devastating scene in Succession where the billionaire Logan Roy tells his adult children, all of whom are failures in different ways: “You are not serious people.”

“Serious”—what a perfect word. Not in the sense of grim or unfunny. More in the sense that visakan veerasamy means it: something like, “actually caring about stuff, and for the right reasons.”

That day, in the lecture hall, none of us were serious. We were all doing a little pantomime on the theme of science. The speaker pretended to show us some results and the we pretended to think about them. As long as we all hit our marks and said our lines, the content didn’t matter—one week you’re doing “Guys and Dolls” and the next week you’re doing “Oklahoma!”, but at the end of the day, it’s all just playacting.

This was the kind of thing that eventually drove me out of academia. I love playing pretend and I love doing science, but not at the same time.

YOU CAN DO WHATEVER YOU WANT, JUST WORK FOR A DICTATOR FIRST

I used to think of seriousness as something to aspire to, a nice-to-have once you figure everything else out. Something you save up for, like a house. “Oh, I’d love to be serious, but in this economy?”

My doubts started creeping in when I got a scholarship to study at Oxford after college, an experience that didn’t go well. One night, while we were standing around drinking wine, the guy in charge of the scholarship told all of us young, promising winners: “What you should really do is go spend a couple years at McKinsey building your skills, and then you can go do whatever you want.”

I had plotted and schemed and sweated to build the world’s best resume, hoping that someone would eventually give me permission to be serious, to start doing things that are good instead of things that look good. Instead, I got permission to go work for the company that does personal branding for dictators.

Before that, I believed what everybody else seems to believe: if you play the game well enough and long enough, eventually you get to stop playing and go do whatever you want. I played the game pretty well for a long time, and now it’s obvious to me that the reward for playing the game is more game. You just keep unlocking levels forever, and the levels don’t even get more interesting (“Ooh, this one is in space!”). It’s just the same thing over and over until you die. You don’t get out by winning; you get out by stopping.

So seriousness isn’t some kind of final reward, a golden watch you earn for a lifetime of operating in bad faith. It is, instead, one of those basic practices you gotta do to prevent your life from disintegrating, like getting out of bed and taking a shower and talking to people. That’s because seriousness is the great Orderer of Priorities, and the Priorities must be Ordered. Otherwise, they grow flabby and unkempt, and you’ll find yourself doing something stupid like working some job you mildly detest or scrolling on your phone, and the next time you look up, seventy years have passed, and now you’re just a skeleton, dead before you ever got around to living.

That’s why you gotta be serious about something. It’s like a protective amulet that prevents you from Goodharting yourself. Unserious people might seem free, unburdened by the dreadful commitment of caring about anything. But they are in fact hackable and distractible, susceptible to whatever game can trap them in a behavior loop. They’re like that guy in that 1990s anti-drug commercial, walking in circles, muttering, “I do coke...so I can work longer...so I can earn more...so I can do more coke.”2

(“I publish papers...so I can get a job...so I can get tenure...so I can publish more papers...”)

Parents apparently have this superpower where they can pick out just their kid’s voice in a room full of screaming children. Seriousness is like that: it allows you to hear the one important thing when the whole universe is screaming at you.

THE CANNONBALL SCHOOL OF SERIOUSNESS

There are three lies that stop people from being serious.

The first lie: seriousness is all or nothing. I often run into people who are like: “Well, I don’t feel like I’m being truly serious and I’m not living up to my values, but I also can’t burn every bridge and change everything about my life, so I guess I’ll just keep doing what I’m doing, forever.”

I used to feel the same way. When I started writing Experimental History, I felt this constant tug to toss everything away and go full-time right now, as if I wasn’t really serious unless I was blogging from sunup to sundown.

But this is like believing that the only way to get into a swimming pool is to do a cannonball off the diving board. Sure, that’s one way to do it, but you’re also allowed to sidle in, inch by inch, going “ooh!” and “oh boy that’s cold!” the whole time. You end up in the same place.

In fact, the inch-by-inch approach might even be better. The person who does the cannonball chooses to be brave once. The person who inches in has to be brave over and over, and that’s what seriousness requires. You don’t flip your Serious Switch one time and now you’re serious forever. Being serious is a tooth-brushing problem—you have to keep doing it every day until you die. Fortunately, the deeper you get into the pool, the more comfortable it gets, and the less comfortable it is to get out.

Plus, there’s always a good reason not to cannonball: it’s too much! Too fast! You can promise yourself you’ll cannonball later, when you’re braver or when the water’s warmer—which is to say, never. But dipping your pinky toe in the pool right now? There’s no reason not to. And then can stick your whole foot in tomorrow, and eventually you can work all the way up to your head.

That’s why, whenever I encounter someone who has endless explanations about why they have to compromise on their values, I know they’re not serious, because they have no answer for, “What’s the tiniest change you’re willing to make right now, today, and that you can make slightly larger tomorrow?”

“I CAN’T BE MOTHER THERESA, SO I MIGHT AS WELL BE MUSSOLINI”

The second lie is really just the first lie wearing a wig. It goes: you have to be serious about everything at once. And that’s impossible, of course, which means you can’t actually be serious about anything.

I encounter this idea all the time when I’m talking to academics about academia. I give ‘em my whole spiel about publishing, being honest, blah blah blah, and they go, “Well, we don’t live in a utopia. You have to make tradeoffs in life.” Yes, of course! But the whole point of tradeoffs is to trade something you value less for something you value more. The thing you care about the most—that’s the thing you don’t compromise on!

(This is, by the way, Negotiations 101.)

For me, I felt like publishing in scientific journals required me to be dishonest. So I stopped publishing in scientific journals. I was willing to make all the other tradeoffs that academia required: uncertain job prospects, low income for a long time, little control over where you end up living, years wasted applying for grants, etc. But I was not willing to compromise on honesty.

Some people don’t feel like journals require them to lie, and good for them, but some people seem to excuse their dishonesty by saying, “Well, it’s fine to lie sometimes because you only ever get, like, 72% of what you want in life, maximum.” No, when you’re serious about something, you get 100% of it, even if it means getting less of something else. If you love someone, for example, you don’t settle for marrying their cousin.

That’s why seriousness is foundational—it tells you what to keep and what to give up. Yes, the world is unfair, corrupt, “no ethical consumption under capitalism,” whatever, but that’s not carte blanche to do whatever you want. “I can’t be Mother Theresa, so I might as well be Mussolini.”

PAYCHECK VOODOO

Finally, the third lie: you’re only serious about something if you’re getting paid to do it.

I know paychecks can do powerful brain-voodoo that makes things seem real. If the memo line says “painter” then you’re a real painter!

But there’s plenty of people pulling down fat stacks who are not serious. Every professor who asked stupid questions of the backslapping study guy—they made good money to dress up and act like scientists, but they were not scientists.

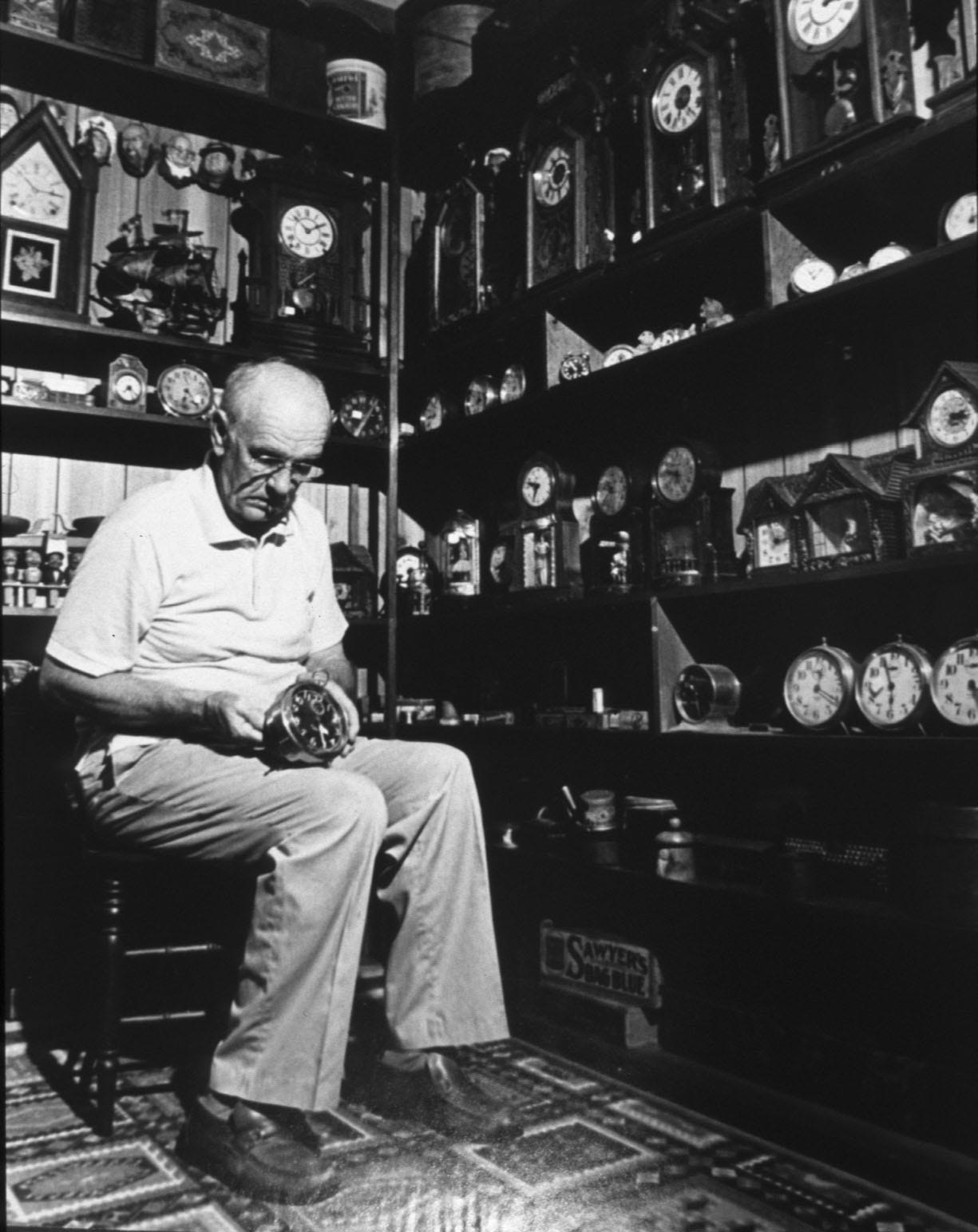

Meanwhile, some of the most serious people I know do their serious thing gratis and make their loot somewhere else. My dad, whose photographs sit at the top of every Experimental History post, quit his job at the newspaper and went to work as a postal carrier instead. Why? As he puts it: “I could afford better lenses delivering mail than I could taking pictures.”

So being serious means ignoring the paycheck’s incantations. But that doesn’t mean ignoring money altogether—you have to figure out how to support yourself and the people who depend on you. You can’t paint your masterpiece if you can’t afford paint. It just doesn’t matter whether the paint money comes from painting or from literally anything else.

SMACK THAT

I don’t know what being serious looks like for you. I barely know what it looks like for me. But no matter who you are, being serious means holding something sacred. And if you don’t feel like you’re doing that right now, it means taking a small but perceptible step toward doing that tomorrow, and then another step after that.

There is not some distant future where it will be easier to be serious, and no one is ever going to give you permission to start. You don’t have to be 100% serious right now, nor do you have to be 100% serious about everything—these are just excuses not to be serious about anything. But the goal is to be 100% serious about at least one thing, and soon.

If you need some help, well, that backslapping paper eventually got published in a prestigious journal, so perhaps the best thing to do is ask a friend to wind up and give you a good, hearty smack right between the shoulder blades.

I’m being vague on the details because I don’t want to dunk on this person in particular; there are hundreds of studies like this.

By the way, the remix slaps.

This was such a wonderful read for me because I’m currently working on my dissertation (on a topic that I care desperately about) and have given up the idea that I want to stay in academia, despite having built a pretty decent little CV for myself so far. I gave up my teaching position and am currently working part-time as a waiter in a low-cost-of-living city, which affords me the time to work on my writing and research. My five-year plan is to spend half my time working in the food and beverage industry and half my time working on my writing and research, and I have to say that approaching the latter two activities without the expectation of using them to acquire a professorship has enabled me to really take them seriously (i.e. to engage in them them without compromising the quality of the product for the sake of the hoards of unserious academics in my field), which is one of the most freeing and exciting feelings ever.

So, by some standards, I’m currently nothing more than a severely overeducated waiter, but waiting tables isn’t only a job that pays the bills (and a job that I am loving, by the way), it’s also enabling me to really take my writing and research seriously, which academia never really allowed me to do (especially because I’m in one of the most humanities-y fields of the humanities).

Anyway, my choices have been unconventional and probably not optimal from the point of view of acquiring wealth and caring for my future financial wellbeing (which has been a source of a bit of ambivalence), but these choices have nevertheless felt like the right choices to make, at least for now, and your post articulates why: because I’d rather take my writing and research seriously than compromise them for the sake of using them to acquire extrinsic rewards.

Anyway, thanks for offering this severely overeducated waiter the encouragement he needs to keep taking his values seriously.

First off - I really love this piece, especially this part:

"I played the game pretty well for a long time, and now it’s obvious to me that the reward for playing the game is more game. You just keep unlocking levels forever, and the levels don’t even get more interesting (“Ooh, this one is in space!”). It’s just the same thing over and over until you die. You don’t get out by winning; you get out by stopping."

Sad to hear (from yet another source) that this is what academia is. But it's in "corporate" life too - you see the "climbers" who think "I'll just put in the hours now, work myself to the bone, and someday I'll move up into a comfortable position." It's simply not true - long hours beget longer hours. As you said, there's no "out" unless you refuse to play at all.

I think one of the biggest pratfalls of American culture (in particular), is this sense that the only thing we should be serious about is our job. I work in middle management at a big company. I prefer my work to be predictable, and at a level I feel that I have a good grasp on. I've gotten good at what I do - but if I look at other positions, they all require a big jump up in commitment, especially more expectations to essentially be "on call" whenever one of my fellow work-o-holics just "needs" an answer at 11pm on a Tuesday. So, no thanks. I don't consider myself "serious" or "passionate" about my work. I give it 90%+ effort every day, but I leave work at work as best I can.

What am I serious about? I'm serious about being a good father and a good husband - two things that get written off as "quaint" at best, "regressive" at worst. But neither is a trivial thing, and both require real seriousness.

I'm also serious about my hobbies, particularly music (listening, playing, writing, etc.) - the things I do for my own satisfaction. I'm not making youtube videos or posting on social media every time I learn a new guitar riff - sharpening skill is for me, not other people. Other people will simply not care as much as you do about a skill or hobby - unless you manage to become famous for it. You do it for yourself, or you're doing it for the wrong reasons, IMO.