Thank you for being annoying

OR: whack 'em if you got 'em

“Do what you love” is the most dangerous sentence in the English language.

We send kids into the world with that mantra in their heads, and then they return shellshocked and ashamed, because they couldn’t do it. Many of them end up believing that they are the one person on Earth who just doesn’t fit in, the sad sap whose preferences and talents—whatever they may be! If they even exist!—simply do not match the opportunities available, like a puzzle piece that got mixed into the wrong box.

Some of them feel that way forever, always a little unsettled and unsatisfied. A few of them turn into cynics, convinced that the idea of a “dream job” is, like the all-seeing Santa Claus, a fiction foisted upon children to keep them docile.

The problem is that nobody ever tells you what it feels like to love something. Everybody thinks love feels like perpetual bliss. It doesn’t. It mainly feels annoying.

THAT WHISKEY FEELING

I’m at the point in my life where I know plenty of people who have “made” it, people who have become the things they always hoped they would be: doctors, lawyers, academics, actors, entrepreneurs, etc., and the one emotion that best describes their daily experience is annoyed.

They’re annoyed! They got exactly what they wanted and, most of the time, it bugs them. When I call them up, they do not wax poetic about how achieving their childhood dreams has brought them deep and everlasting happiness. They tell me about their dumbass bosses, their crazy patients, the cases that are driving them nuts, the prototypes that they can’t get working.

Some of these people are honked off because they’ve chosen the wrong career. But most of them will tell you that they love their jobs, and they mean it. Which is weird because, if you watch them closely, they do not spend their workdays laughing and smiling and saying things like “yippee!” or “wahoo!”. They are, most of the time, mad about something. Same goes for me—I’m annoyed all day. And yet none of us can stop. When we say, “I love my job,” we really mean, “My job pisses me off, but in an enchanting way.”

What’s going on here?

I think annoyance, like cholesterol, has a good kind and a bad kind. The bad kind makes you want to flee: backed-up traffic, crying babies on planes, colleagues who say they can use Excel when really they mean they’ve heard of Excel. But the good kind of annoyance draws you in rather than driving you away. It’s that feeling you get when there’s something you can and must make right, the way some people feel when they see a picture frame that’s just a bit askew, except a lot more and all the time.

Whenever I fix the thing that’s annoying me, it does feel “fun”, I guess, but it’s not fun in the way that, say, going down a waterslide is fun. It’s a textured pleasure, the kind of enjoyment I assume that whiskey enthusiasts get from drinking extremely peaty, smoky scotch—on the one hand, it burns, but on the other hand, I kinda like how it burns.

Good annoyance is, I think, the only thing that keeps people coming back for more, indefinitely. There is nothing that a human with a normally-functioning brain can do for eight hours a day, every day, for their whole career, that feels “fun” the whole time, or even a large fraction of the time. We’re just too good at adapting to things. And thank God, because if we never got bored, we never would have survived. Our ancestors would have spent their days staring doe-eyed and slack-jawed at, like, a really pretty leaf or something, and they would have gotten eaten by leopards. Fun fades, but irritation is infinite.

The right job for you, then, is the one that puts you in charge of the things that annoy you. And this is where we steer people wrong. We imply that the right occupation for them is the one that lets them float through their days in a kind of dreamy pleasantness, when in fact they should be alternating between vexation and gratification. Or we let them choose proximity over responsibility, prioritizing what they’re working in rather than what they’re working on.

I had a lot of artsy friends in college who did this after graduation—they wanted to play Hamlet, but they instead ended up drafting marketing emails for a summer repertory production of Guys and Dolls. It’s no surprise that they hated this, because being in the presence of your annoyances without being in control of them is a recipe for insanity. That’s like working at the Museum of Slightly Crooked Pictures, where all the frames are wonky but you’re not allowed to straighten them.

TAPEWORM, YUM

Good annoyance is ultimately the recipe for greatness. It certainly seems that way, at least, because the people the top of their game always seem kinda ticked off. You’d think that folks who are famous for being good at something would experience intense pleasure all the time from doing that thing; otherwise, how can they stand to do it so much? Plus, everybody’s always telling them how wonderful they are, and that must feel great. And yet, when these people are candid about what’s going on in their heads, it turns out to be a little complicated in there. For instance, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Mario Vargas Llosa likened being a writer to having a tapeworm inside you:

The literary vocation is not a hobby, a sport, a pleasant leisure-time activity. […] Like [my friend] José Maria’s tapeworm, literature becomes a permanent preoccupation, something that takes up your entire existence, that overflows the hours you devote to writing and seeps into everything else you do, because the literary vocation feeds off the life of a writer just as the tapeworm feeds off the bodies it invades.

Here’s Andre Agassi on tennis:

I play tennis for a living, even though I hate tennis, hate it with a dark and secret passion, and always have. [...] I slide to my knees and in a whisper I say: Please let this be over.

Then: I’m not ready for it to be over.

Marie Curie on getting an education:

One never notices what has been done; one can only see what remains to be done.

Billy Mitchell, one of the best Pac-Man players in the world, on playing Pac-Man:

I enjoy the victory of it, but it’s pure pain [...] I don’t know anything about a zone, or getting into a flow. It’s constant intensity and concentration. Nothing’s flowing. You squeeze a joystick in your hand for hours and it starts to feel like it’s going to shatter your hand.

And Meryl Streep on acting:

Bleehhh...eehhh...uhh...god, I hate this sometimes.

Every beginner needs to have their nose rubbed in this idea. When you’re just starting out, it’s easy to think that expertise will cure your doubts and conquer your frustrations, that you’ll unlock a higher plane of pleasure once you can play in tune, sink a shot, or write a sentence that doesn’t suck.

Maybe I’ve just never gotten that good at anything, but this has never happened to me. I have never conquered my doubts and frustrations; I merely traded them in for newer models. I can do more with less effort, but nothing feels effortless. If anything, I’m more annoyed than when I started. That’s why I’m still here. I wonder: is this how it will always feel? That’s what I’m afraid of, and what I’m hoping for.

WHACK ‘EM IF YOU GOT ‘EM

How can something feel so good and so bad at the same time?

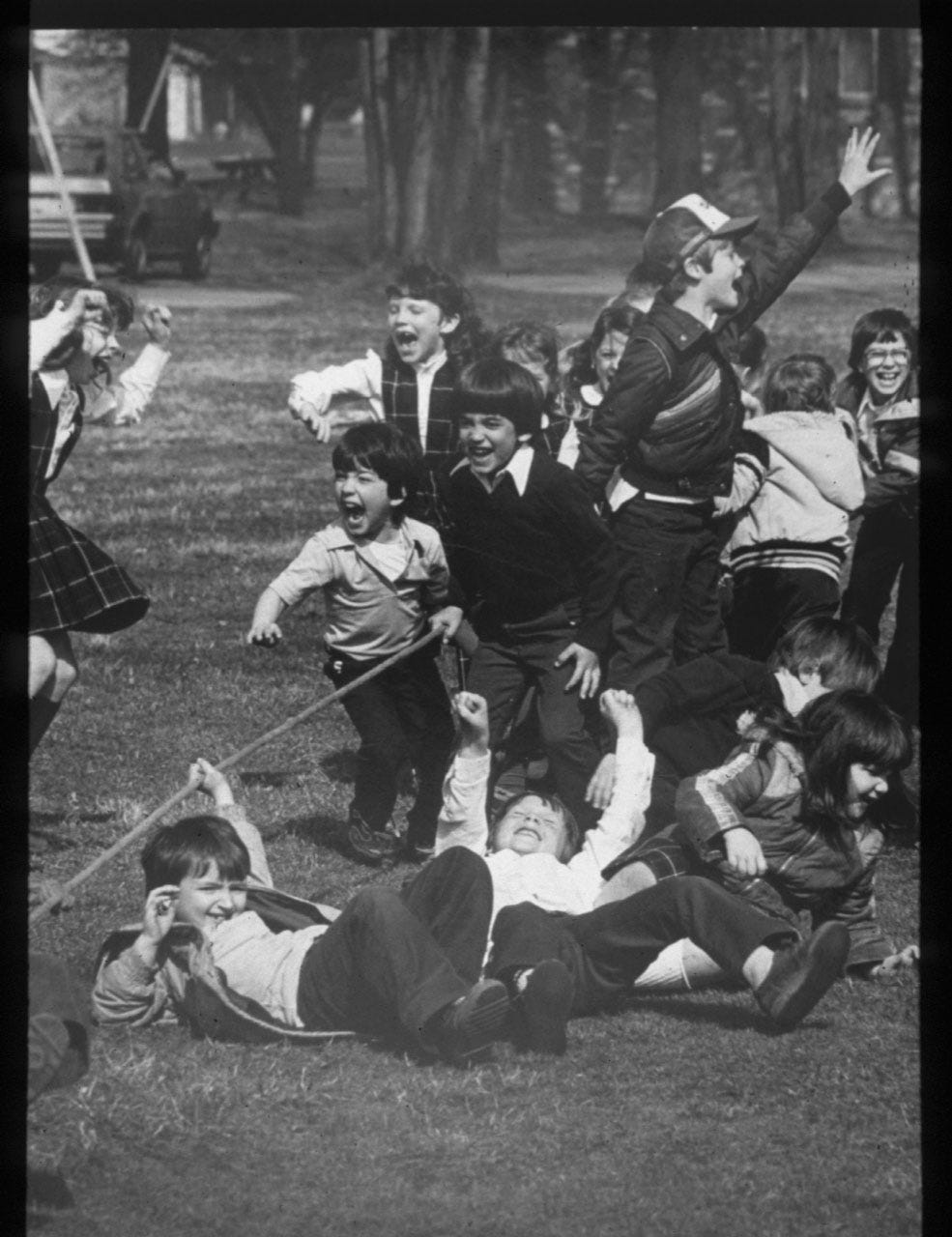

Here’s an explanation. According to the cybernetic theory of psychology, the mind is a stack of control systems all trying to keep things copacetic. In this model, happiness comes not from the absence of error in these systems, but from the correction of error. That is, happiness isn’t a full belly, it’s a belly that’s being filled. So if you wanna feel good, you gotta let things get at least a little out of whack so you can whack them back into place again. The whacking is, in fact, the fun part.

This is why rich folks do extreme sports, why childless retirees spend their days on make-work projects of pretend importance, and why lottery winners very rarely quit their jobs. Everyone has this dream of a frictionless existence; nobody seems to like it much when they get it. Infinity pools and bottomless margaritas are fine for a time, but eventually you start wishing the moles would pop back up again so you could hit ‘em with a mallet.

This out-of-whack/back-in-whack cycle is not a source of motivation. It is motivation. Annoyance is the only truly renewable resource known to man.

When people try and fail to increase their “productivity”, it’s because they miss this point. There is no system that can conjure up annoyance where there isn’t any. You cannot trick yourself into caring about something by putting it on your Google calendar. If you have a productivity problem, you’re either not annoyed enough, you’re annoyed by something you can’t actually control, or you’re annoyed in the bad way, the kind that makes you want to skip town rather than dig in.

It’s easy to get stuck on the wrong problems because we have such strong theories about the things we should care about. But we don’t really get to pick the things that bug us. Why are some people annoyed by crooked picture frames while other people get annoyed by securities fraud, or bland chicken parmesan, or inefficient assembly lines? I dunno man, people are crazy. There’s one guy who is so annoyed at people using the phrase “comprised of” when they actually mean “composed of” that he fixes it on tens of thousands of Wikipedia pages. No amount of to-do lists, bullet journals, pomodoros, kanbans, Moscow methods, Eisenhower decision matrices, or frog-eating can rival the power of one dude who is pissed off in a very specific way.

THE COLD PRICKLIES

Human motivation didn’t evolve so we could show up to work on time. This irritation-reduction system drives everything we do, regardless of whether we get a paycheck for it. That includes even the most selfless acts, the ones that we’re supposed to do despite our motivations.

Recently, some of my friends were swapping stories about surprisingly kind strangers, and I couldn’t help but notice that every Good Samaritan had acted out of annoyance. A construction worker spotted something amiss with my friend’s bike chain while she was waiting at a red light, and he came over and knocked it back into place, telling her, “I just can’t bear to see it like that.” Another friend was moving into an apartment, and their new neighbor spotted them struggling with a couch and came over to help, muttering “I can’t watch you guys do this on your own.” A third returned an envelope of cash they found because they, “Would hate to be the kind of person who kept it for themselves.”

I think this is actually the way most good-hearted people work: they’re motivated not by warm fuzzies, but by cold pricklies. They help because they can’t stand the sight of someone in need. The golden glow of altruism comes later, if at all, when they’re walking home and thinking about what a good person they are.

The causes that we stick with, then, aren’t the ones that do the most good, nor the ones that align with whatever we think are our most fundamental values. No, we stick with the causes that give us the same perverse pleasure that you get from popping a pimple.

We’d do a lot more for each other if we acknowledged this fact. Altruism doesn’t need to feel like pure self-flagellation or pure self-congratulation. A lot of the time, if you’re doing it right, it’ll feel irritating. Not all heroes wear capes—some of them wear an exasperated look of “are you seriously trying to lift that couch by yourselves”.

THE DAY VANESSA GOT DUMPED

What if love itself is just another instance of good annoyance?

I had this friend in high school, let’s call her Vanessa. I ran into her once a couple years after graduation, when she was living with her boyfriend and madly in love with him. I was skeptical of all things love at the time, so I asked her, “How can anyone ever truly love someone else? What about when your boyfriend has diarrhea? Do you still love him then?” Vanessa scoffed. When her boyfriend has diarrhea, she said, it doesn’t really have anything to do with her. Their relationship is about the nice stuff, not the nasty stuff.

A year later, Vanessa came home from work early and found her boyfriend in bed with another woman.1 It turned out, unfortunately, he did a lot of nasty things that didn’t have anything to do with her.

I think Vanessa and I were both wrong. Yes, it is your business when the person you love has diarrhea, but no, you don’t have to be happy about it. You can be in love and still be annoyed. In fact, love may require a certain amount of frustration because, as Ava of bookbear express puts it, “closeness is fundamentally annoying”:

Closeness is annoying because it’s about the surrender of control. You’re trying to fall asleep, and beside you your partner is snoring. You lightly push their jaw to the side so it’ll stop. Two minutes later, the snoring commences again. You lay there in the dark wondering how you got here. Oh, right: three years ago at a party you saw someone and thought they were very beautiful.2

A lot of people who are confused about love are actually waiting for permission to feel annoyed. They think love is supposed to make you crazy in the cartoon sense, where the mere presence of your beau will make your eyes turn into hearts and go AWOOGA. Love does drive you crazy like that, but it also drives you crazy in the sense of “my spouse only likes three songs and insists on playing them over and over again on our roadtrip”. If you’re looking for the person who will never annoy you, you’ll never stop looking. But if you find someone who annoys you juuust right, you’ll never stop loving them, nor will you ever get to hear a song in the car that is not “Go Your Own Way” by Fleetwood Mac.

BUGGIN’

I always thought that negative emotions were bad. (“Negative” is right there in the name.) Whenever I felt sad or upset or whatever, I’d be like, “oh no!! A bad feeling!! Something’s gone wrong!! I need to speak to a manager!!” Every foul mood felt like an emergency, like the forces of darkness had breached the keep and were killing my dudes and smashing all my nice things.

I know that half the world has beaten me to this realization, but there’s no such thing as an emotion that’s purely bad or purely good. Emotions aren’t solid tones, like a middle C ringing out at exactly 261 hertz—not the interesting ones, anyway. Nobody pops in their AirPods to listen to four straight minutes of G major chords. The music that holds our attention has overtones, dissonances, dynamics, and syncopation; it has bits you like less, bits you like more, and bits you didn’t think you liked but you actually do.

Same goes for any emotion that’s strong enough to hold our attention for a long time. All of my fixations have centered around my irritations. That squeeze and release, the indignation and the elation, the rage and the rapture—it feels good and it feels bad and mainly it feels necessary.

So maybe the question we should be asking young folks is not “what do you love?” but “what bugs the hell out of you?” What can’t you stand, and what can’t you quit? People say “do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life” and they’re right, because you’ll get bored and go home. If you find the job, the cause, and the partner that annoy you in exactly the right way, you’ll never know peace again. Nor will you want to. Please let it be over, I’m not ready for it to be over!

This was back in the early days of Facebook, before people had realized that the purpose of social media is to make yourself look good rather than bad.

Credit to Ava’s post for inspiring mine.

I think it is simpler than this. Rather than telling people to do what they love, we should tell them to serve what they love. When we serve what we love, we tackle the annoyances joyfully, because that is the nature of the service we seek to give. Indeed, when we serve what we love, we seek out the area of greatest annoyance because that is where the greatest opportunity for service exists.

"It's a textured pleasure" is one of the best ways I've ever heard this sensation described. Thanks for another wonderful read, Adam.