Face it: you're a crazy person

OR: why your brain needs a boxcutter

I meet a lot of people who don’t like their jobs, and when I ask them what they’d rather do instead, about 75% say something like, “Oh, I dunno, I’d really love to run a little coffee shop.” If I’m feeling mischievous that day, I ask them one question: “Where would you get the coffee beans?”

If that’s a stumper, here are some followups:

Which kind of coffee mug is best?

How much does a La Marzocco espresso machine cost?

Would you bake your blueberry muffins in-house or would you buy them from a third party?

What software do you want to use for your point-of-sale system? What about for scheduling shifts?

What do you do when your assistant manager calls you at 6am and says they can’t come into work because they have diarrhea?

The point of the Coffee Beans Procedure is this: if you can’t answer those questions, if you don’t even find them interesting, then you should not open a coffee shop, because this is how you will spend your days as a cafe owner. You will not be sitting droopy-lidded in an easy chair, sipping a latte and greeting your regulars as you page through Anna Karenina. You will be running a small business that sells hot bean water.

The Coffee Beans Procedure is a way of doing what psychologists call unpacking. Our imaginations are inherently limited; they can’t include all details at once. (Otherwise you run into Borges’ map problem—if you want a map that contains all the details of the territory that it’s supposed to represent, then the map has to be the size of the territory itself.) Unpacking is a way of re-inflating all the little particulars that had to be flattened so your imagination could produce a quick preview of the future, like turning a napkin sketch into a blueprint.1

When people have a hard time figuring out what to do with their lives, it’s often because they haven’t unpacked. For example, in grad school I worked with lots of undergrads who thought they wanted to be professors. Then I’d send ‘em to my advisor Dan, and he would unpack them in 10 seconds flat. “I do this,” he would say, miming typing on a keyboard, “And I do this,” he would add, gesturing to the student and himself. “I write research papers and I talk to students. Would you like to do those things?”

Most of those students would go, “Oh, no I would not like to do those things.” The actual content of a professor’s life had never occurred to them. If you could pop the tops of their skulls and see what they thought being a professor was like, you’d probably find some low-res cartoon version of themselves walking around campus in a tweed jacket going, “I’m a professor, that’s me! Professor here!” and everyone waving back to them going, “Hi professor!”

Or, even more likely, they weren’t picturing anything at all. They were just thinking the same thing over and over again: “Do I want to be a professor? Hmm, I’m not sure. Do I want to be a professor? Hmm, I’m not sure.”

Why is it so hard to unpack, even a little bit? Well, you know how when you move to a new place and all of your unpacked boxes confront you every time you come home? And you know how, if you just leave them there for a few weeks, the boxes stop being boxes and start being furniture, just part of the layout of your apartment, almost impossible to perceive? That’s what it’s like in the mind. The assumptions, the nuances, the background research all get taped up and tucked away. That’s a good thing—if you didn’t keep most of your thoughts packed, trying to answer a question like “Do I want to be a professor?” would be like dumping everything you own into a giant pile and then trying to find your one lucky sock.

THE BEAST AND THE WOLFF

When you fully unpack any job, you’ll discover something astounding: only a crazy person should do it.

Do you want to be a surgeon? = Do you want to do the same procedure 15 times a week for the next 35 years?

Do you want to be an actor? = Do you want your career to depend on having the right cheekbones?

Do you want to be a wedding photographer? = Do you want to spend every Saturday night as the only sober person in a hotel ballroom?

If you think no one would answer “yes” to those questions, you’ve missed the point: almost no one would answer “yes” to those questions, and those proud few are the ones who should be surgeons, actors, and wedding photographers.

High-status professions are the hardest ones to unpack because the upsides are obvious and appealing, while the downsides are often deliberately hidden and tolerable only to a tiny minority. For instance, shortly after college, I thought I would post a few funny videos on YouTube and, you know, become instantly famous2. I gave up basically right away. I didn’t have the madness necessary to post something every week, let alone every day, nor did it ever occur to me that I might have to fill an entire house with slime, or drive a train into a giant pit, or buy prosthetic legs for 2,000 people. If you read the “leaked” production guide written by Mr. Beast, the world’s most successful YouTuber, you’ll quickly discover how nutso he is:

I’m willing to count to one hundred thousand, bury myself alive, or walk a marathon in the world’s largest pairs of shoes if I must. I just want to do what makes me happy and ultimately the viewers happy. This channel is my baby and I’ve given up my life for it. I’m so emotionally connected to it that it’s sad lol.

(Those aren’t hypothetical examples, by the way; Mr. Beast really did all those things.)

Apparently 57% of Gen Z would like to be social media stars, and that’s almost certainly because they haven’t unpacked what it would actually take to make it. How many of them have Mr. Beast-level insanity? How many are willing to become indentured servants to the algorithm, to organize their lives around feeding it whatever content it demands that day? One in a million?

Another example: lots of people would like to be novelists, but when you unpack what novelists actually do, you realize that basically no one should be a novelist. For instance, how did Tracy Wolff, author of the Crave “romantasy” series, become one of the most successful writers alive? Well, this New Yorker piece casually mentions that Wolff wrote “more than sixty” books between 2007 and 2018. That’s 5.5 novels per year, every year, for 11 years, before she hit it big. And she’s still going! She has so many books now that her website has a search bar. Or you can browse through categories like “Contemporary Romance (Rock Stars/Bad Boys)”, “Contemporary Erotic Billionaire Romance”, “Contemporary Romance (Harlequin Desire)”, and “Contemporary New Adult Romance (Snowboarders!)”.

Wolff and Beast might seem extreme, but they’re only extreme in terms of output, not in terms of time on task. This is the obvious-but-overlooked insight that you find when you unpack: people spend so much time doing their jobs. Hours! Every day! It’s 2pm on a Tuesday and you’re doing your job, and now it’s 3:47pm and you’re still doing it. There’s no amount of willpower that can carry you through a lifetime of Tuesday afternoons. Whatever you’re supposed to be doing in those hours, you’d better want to do it.

For some reason, this never seems to occur to people. I was the tallest kid in my class growing up, and older men would often clap me on the back and say, “You’re gonna be a great basketball player one day!” When I’d balk, they’d be like, “Don’t you want to be on a team? Don’t you want represent your school? Don’t you want to wear a varsity jacket and go to regionals?” But those are the wrong questions. The right questions, the unpacked questions, are: “Do you want to spend three hours practicing basketball every day? Do you want to dribble and shoot over and over again? On Thursday nights, do you want to ride the bus and sit on the bench while your more talented friends compete, secretly hoping that Brent sprains his ankle so you could have a chance to play?” And honestly, no! I don’t! I’d rather be at home playing Runescape.

When you come down from the 30,000-foot view that your imagination offers you by default, when you lay out all the minutiae of a possible future, when you think of your life not as an impressionistic blur, but as a series of discrete Tuesday afternoons full of individual moments that you will live in chronological order and without exception, only then do you realize that most futures make sense exclusively for a very specific kind of person. Dare I say, a crazy person.

Fortunately, I have good news: you are a crazy person.

YOU’RE NUTS

I don’t mean you’re crazy in the sense that you have a mental illness, although maybe you do. I mean crazy in the sense that you are far outside the norm in at least one way, and perhaps in many ways.

Some of you guys wake up at 5am to make almond croissants, some of you watch golf on TV, and some of you are willing to drive an 80,000-pound semi truck full of fidget spinners across the country. There are people out there who like the sound of rubbing sheets of Styrofoam together, people who watch 94-part YouTube series about the Byzantine Empire, people who can spend an entire long-haul flight just staring straight ahead. Do you not realize that, to me, and to almost everyone else, you are all completely nuts?

No, you probably don’t realize that, because none of us do. We tend to overestimate the prevalence of our preferences, a phenomenon that psychologists call the “false consensus effect”3. This is probably because it’s really really hard to take other people’s perspectives, so unless we run directly into disconfirming evidence, we assume that all of our mental settings are, in fact, the defaults. Our idiosyncrasies may never even occur to us. You can, for instance, spend your whole life seeing three moons in the sky, without realizing that everybody else sees only one:

the first time i looked up into the night sky after i got glasses, [I] realized that you can, in fact, see the moon clearly. i assumed people who depicted it in art were taking creative license bc they knew it should look like that for some reason, and that the human eye was incapable of seeing the moon without also seeing two other, blurrier moons, sort of overlapping it

In my experience, whenever you unpack somebody, you inevitably discover something extremely weird about them. Sometimes you don’t have to dig that far, like when your friend tells you that she likes “found” photographs—the abandoned snapshots that turn up at yard sales and charity shops—and then adds that she has collected 20,000 of them. But sometimes the craziness is buried deep, often because people don’t think it’s crazy at all, like when a friend I knew for years casually disclosed that she had dumped all of her previous boyfriends because they had been insufficiently “menacing”.

DR. PIMPLE POPPER WILL SEE YOU NOW

This is why people get so brain-constipated when they try to choose a career, and why they often pick the wrong one: they don’t understand the craziness that they have to offer, nor the craziness that will be demanded of them, and so they spend their lives jamming their square-peg selves into round-hole jobs. For example, when I was in academia, there was this bizarre contingent of administrators who found college students vaguely vexing and exasperating. When the sophomores would, say, make a snowman in the courtyard with bodacious boobs, these dour admins would shake their heads and be like, “College kids are a real pain in the ass, huh!” They didn’t seem to realize that their colleagues actually liked hanging out with 18-22 year-olds, and that the occasional busty snowman was actually what made the job interesting. I don’t think these curmudgeonly managers even thought such a preference was possible.

Another example: when I was a pimply-faced teenager, I went to this dermatologist who always seemed annoyed to see patients. Like, how dare we bother him by seeking the services that he provides? Meanwhile, Dr. Pimple Popper—a YouTube account that does exactly what it says on the tin—has nearly 9 million subscribers. Clearly, there are people out there who find acne fascinating, and dermatology is the one of the most competitive medical specialties, but apparently you can, through sheer force of will, lack of self-knowledge, and refusal to unpack the details, earn the right to do a job you hate for the rest of your life.

On the other hand, when people match their crazy to the right outlet, they become terrifyingly powerful. A friend from college recently reminded me of this guy I’ll call Danny, who was crazy in a way that was particularly useful for politics, namely, he was incapable of feeling humiliated. When Danny got to campus freshman year, he announced his candidacy for student body president by printing out like a thousand copies of his CV—including his SAT score!—and plastering them all over campus. He was, of course, widely mocked. And then the next year, he won. It turns out that people vote for the name that they recognize, and it doesn’t really matter why they recognize it. By the time Danny ran for reelection and won in a landslide, he was no longer the goofy freshman who taped a picture of his own face to every lamp post. At that point, he was the president.45

COPS FOR TEENS

Unpacking is easy and free, but almost no one ever does it because it feels weird and unnatural. It’s uncomfortable to confront your own illusion of explanatory depth, to admit that you really have no idea what’s going on, and to keep asking stupid questions until that changes.

Making matters worse, people are happy to talk about themselves and their jobs, but they do it at this unhelpful, abstract level where they say things like, “oh, I’m the liaison between development and sales”. So when you’re unpacking someone’s job, you really gotta push: what did you do this morning? What will you do after talking to me? Is that what you usually do? If you’re sitting at your computer all day, what’s on your computer? What programs are you using? Wow, that sounds really boring, do you like doing that, or do you endure it?

You’ll discover all sorts of unexpected things when unpacking, like how firefighters mostly don’t fight fires, or how Twitch streamers don’t just “play video games”; they play video games for 12 hours a day. But you’re not just unpacking the job; you’re also unpacking yourself. Do any aspects of this job resemble things you’ve done before, and did you like doing those things? Not “Did you like being known as a person who does those things?” or “Do you like having done those things?” but when you were actually doing them, did you want to stop, or did you want to continue? These questions sound so stupid that it’s no wonder no one asks them, and yet, somehow, the answers often surprise us.

That’s certainly true for me, anyway. I never unpacked any job I ever had before I had it. I would just show up on the first day and discover what I had gotten myself into, as if the content of a job was simply unknowable before I started doing it, a sort of “we have to pass the bill to find out what’s in it” kind of situation. That’s how I spent the summer of 2014 as a counselor at a camp for 17-year-olds, even though I could have easily known that job would require activities that I hated, like being around 17-year-olds. Could I have known specifically that my job would include such tasks as “escorting kids across campus because otherwise they’ll flee into the woods” or “trying to figure out whether anyone brought booze to the dance by surreptitiously sniffing kids’ breath?” No. But had I unpacked even a little bit, I would have picked a different way to spend my summer, like selling booze to kids outside the dance.

It’s no wonder that everyone struggles to figure what to do with their lives: we have not developed the cultural technology to deal with this problem because we never had to. We didn’t exactly evolve in an ancestral environment with a lot of career opportunities. And then, once we invented agriculture, almost everyone was a farmer the next 10,000 years. “What should I do with my life?” is really a post-1850 problem, which means, in the big scheme of things, we haven’t had any time to work on it.

The beginning of that work is, I believe, unpacking. As you slice open the boxes and dump out the components of your possible futures, I hope you find the job that’s crazy in the same way that you are crazy. And then I hope you go for it! Shoot for the stars! Even if you miss, you’ll still land on one of the three moons.

You can think of unpacking as the opposite of attribute substitution; see How to Be Wrong and Feel Bad.

In my defense, this was a decade ago, closer to the days when you could become world famous by doing a few different dances in a row.

There is also a “false uniqueness effect”, but it seems to show up more rarely, on traits where people are motivated to be better than others, or when people have biased information about themselves. So people who like Hawaiian pizza probably think their opinion is more common than it is (false consensus). But if you pride yourself on the quality of your homemade Hawaiian pizza, you probably also overestimate your pizza-making skills (false uniqueness).

I’m pretty sure every campus politician was like this. During one election cycle, the pro-Palestine and pro-Israel groups started competing petitions to remove/keep a brand of hummus in the dining hall that allegedly had ties to the IDF. One of the guys running for class rep signed both petitions. When someone called him out, his response was something like, “I’m just glad we’re having dialogue.” Anyway, he won the election.

A few years later, a sophomore ran for student body president on a parody campaign, promising waffle fries and “bike reform.” He won a plurality of votes in the general election, but lost in the runoff, though he did get a write-up in the New York Times. Now he’s a doctor.

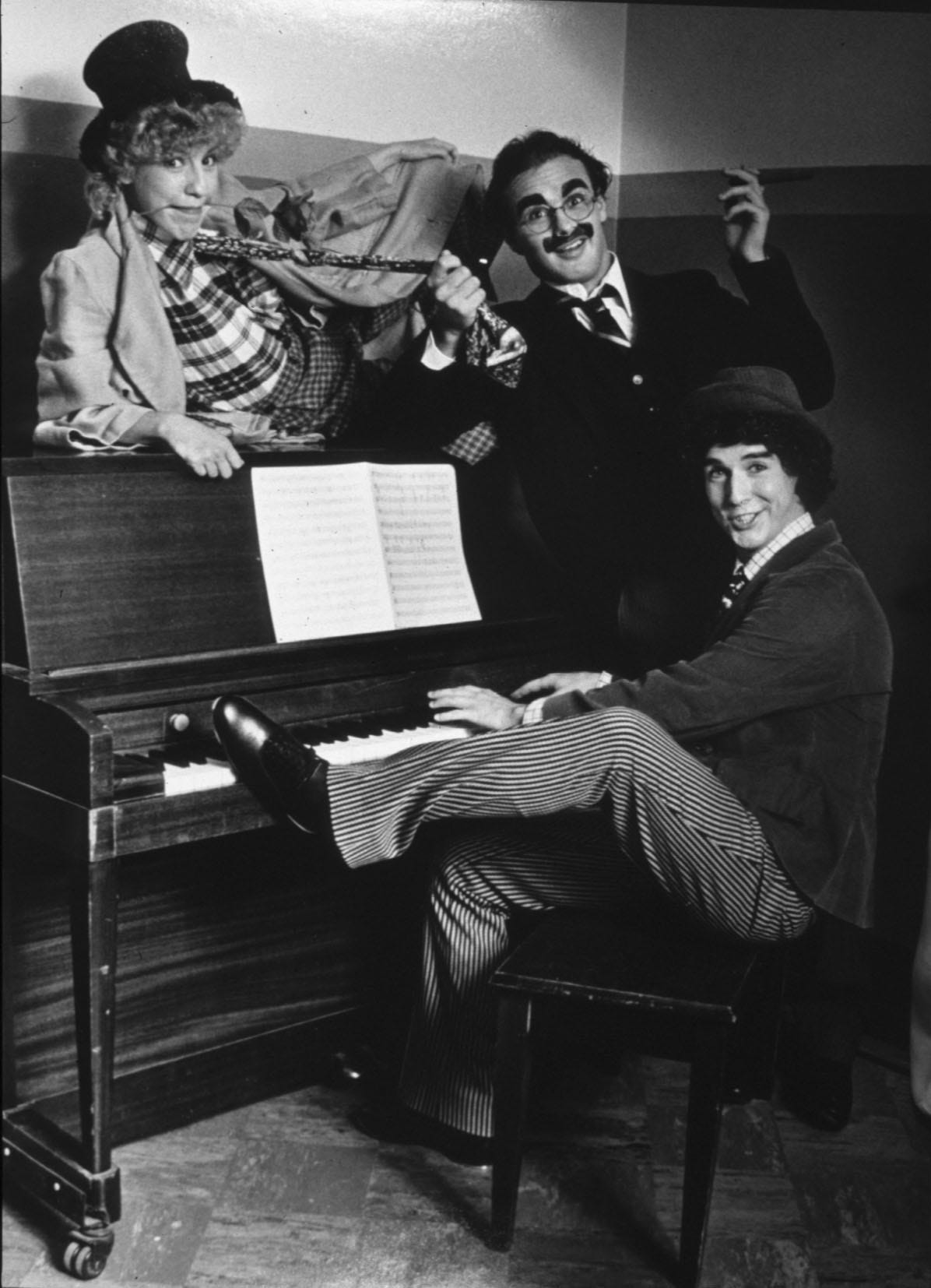

Top-tier insanity can sometimes make up for mid-tier talent. I’ve been in five-ish different improv communities, and in every single one there was someone who was pretty successful despite not being very good at improv. These folks were willing to mortgage the rest of their life to support their comedy habit—they’d half-ass their jobs, skip class, ignore their partners and kids, and in return they could show up for every audition, every gig, every side project. Their laser focus on their dumb art didn’t make them great, but it did make them available. Everybody knew them because they were always around, and so when one of your cast mates dropped out at the last second and you needed someone to fill in, you’d go, “We can always call Eric.” If you’ve ever seen someone on Saturday Night Live who isn’t very funny and wondered to yourself, “How did they get there?”, maybe that’s how.

I feel targeted by this post. I was a tall teen who didn’t actually want to play basketball, and now after a decade of unpacking the academia career path (turns out I’m paid to be a cop, not a teacher) I’m starting a coffee business—but at least I have answers to the opening questions.

Great post, but I will add one critique. Many people, me included, will eventually have to choose between what they enjoy and what they are good at. I enjoy making music and can spend hours playing guitar. After 40 years of practice, I am almost good enough to play in the worst imaginable bar cover band. However, I am a fairly good professor and academic administrator, but it’s been a daily grind. My aptitudes and interests have never been a great match.