The end is nigh and here's why

OR: Good Cup Bad Cup

In fourteen hundred and ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue…because he thought the apocalypse was coming.

Like many of his contemporaries, Columbus believed that the Earth was supposed to last for 7,000 years total, with only ~150 years remaining. More importantly, God had left us a list of things he wanted us to get done before he returned, which included “convert everybody to Christianity,” and “rebuild the temple in Jerusalem.” Columbus saw himself as critical to achieving both goals: he would discover new sea routes to speed up the evangelization of the world, and his success in that mission would prove he was also the man to tackle the temple job.1

So the most pivotal voyages in history happened because one guy wanted to tick some things off the divine to-do list before Jesus returned to vaporize the sinners and valorize the saints. But that’s not the weird part.

What’s really weird is that, in the big scheme of things, Columbus’ ideas are totally normal. Apocalyptic expectations are so common across time and place that they seem like the cosmic background radiation of the mind. Many people, while going about their business, are thinking to themselves, “Well, this will all be over soon.”

That remains true today. Nearly half of Christians in America believe that Jesus will “definitely” or “probably” return by 2050.2 A similar proportion of Muslims living in the Middle East and North Africa believe they will live to see the end times. In 2022, 39% of Americans said we’re living in the end times right now.

If you ask a psychologist why so many people expect the world to end, they’ll probably invoke terror management theory—maybe believing that armageddon is a-comin’ somehow helps us cope with the inevitable fact of our own deaths. Rather than getting your ticket punched at some random time by a stroke, a tumor, or a drunk driver, wouldn’t you rather believe you’ll go out in a blaze of godly glory that could be predicted in advance?

That might make sense for someone like Columbus, who gave himself a leading role in the end of the world. But for the rest of us stuck in the chorus line, doesn’t the impending doom seems kinda...stressful? Even if the end times ultimately lead to the Kingdom of God, most prophecies are pretty clear that there will be lots of wailing and gnashing of teeth beforehand: earthquakes and famines, Antichrists everywhere, not to mention the deafening trumpet blasts from a sort of celestial, apocalyptic ska band. Plus, most of the folks who think the end is nigh will admit they don’t know exactly how nigh it is, so it’s not like they can take solace in planning their outfits for the big day.

I’ve got a different theory: people are predisposed to believe the end is coming not because it feels good, but because it seems reasonable.

GOOD CUP BAD CUP

In The Illusion of Moral Decline, my coauthor Dan and I showed how two biases could lead people to believe that humans are getting nastier over time, even when they’re not.

Humans pay more attention to bad things vs. good things in the world. And they’re more likely to transmit info about bad things—the news is about planes that crashed, not planes that landed, etc. We call this part biased attention.

In memory, the negativity of bad stuff fades faster than the positivity of good stuff. There’s a good reason for this: when bad things happen, we try to rationalize them, reframe, distance, explain them away, etc., all things that sap the badness. (Much of this might be automatic and unconscious.) But we don’t do that when good things happen, and so good things keep their shine longer than bad things keep their sting. We call this part biased memory.3

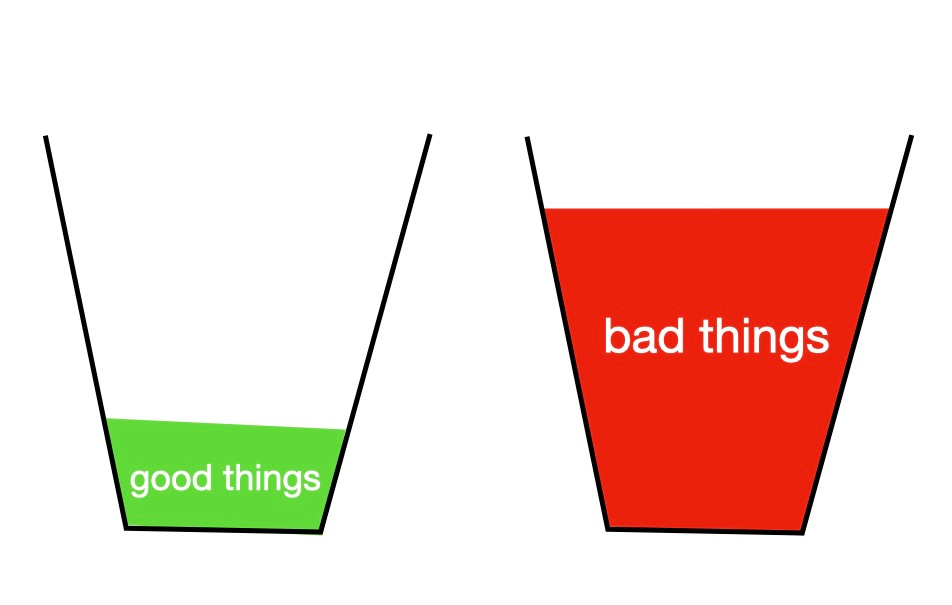

Here’s what it looks like when you combine those two tendencies. Imagine you’ve got two cups in your head: a Bad Cup that fills up when you see bad things, and a Good Cup that fills up when you see good things. Every day you look out on the world, and thanks to biased attention, the Bad Cup gets fuller than the Good Cup.

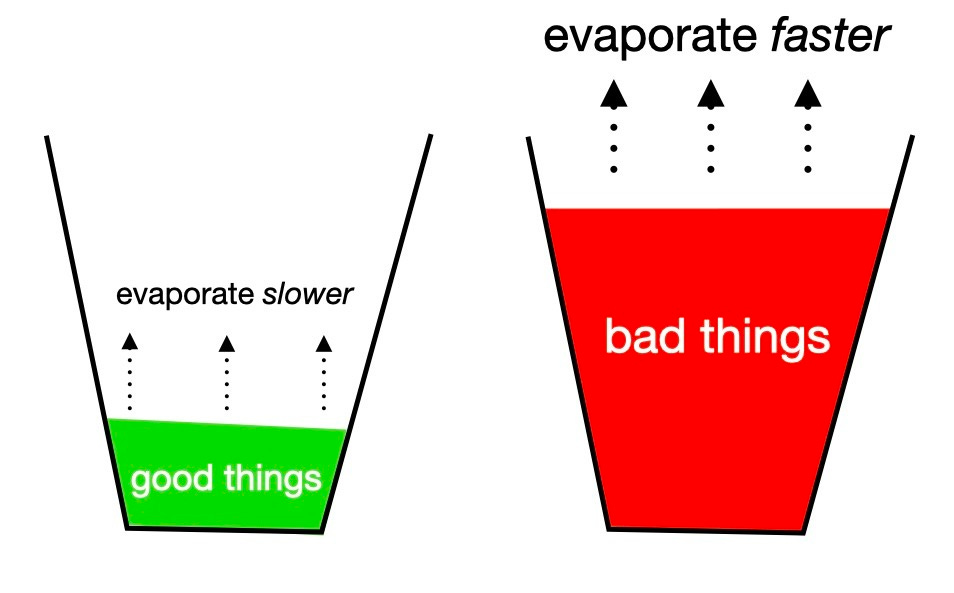

But thanks to biased memory, stuff in the Bad Cup evaporates faster than stuff in the Good Cup:

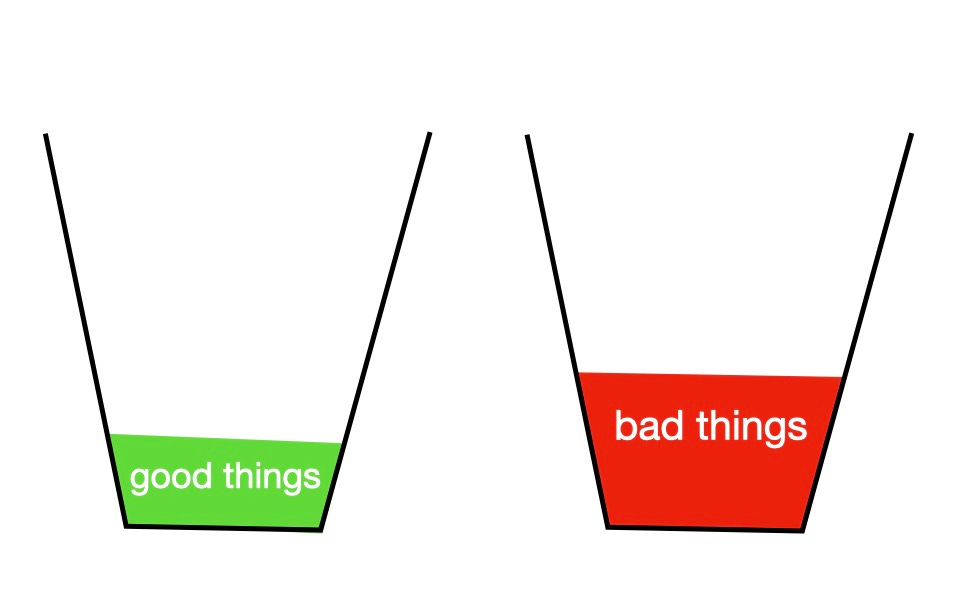

When you remember the past, then, the Good Cup has lost some good stuff, but the Bad Cup has lost even more bad stuff:

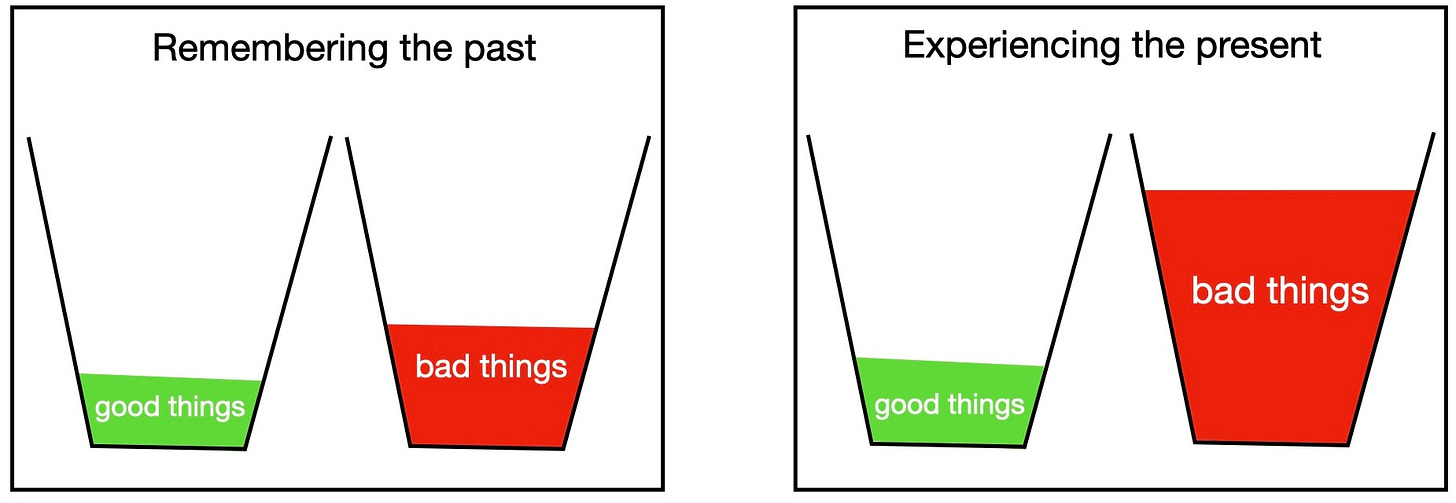

So when you compare the past to the present, it seems like there was a more positive ratio of Good Cup to Bad Cup back then:

That can explain why things always seem bad and why things always seem like they’re getting worse. Which is exactly what we see in the data: every year, people say that humans just aren’t as kind as they used to be, and every year they rate human kindness exactly the same as they did last year.

(Of course, depending on the rates of evaporation and how far back you go, you could eventually get to a point where the Good Cup is actually fuller than the Bad Cup.4)

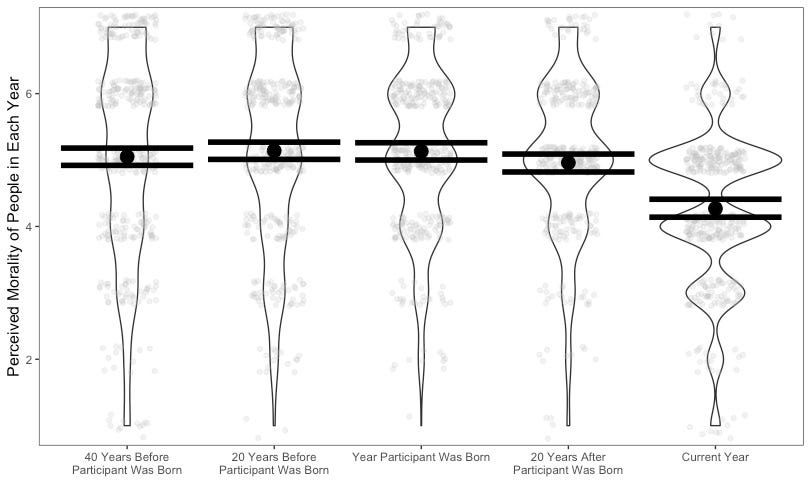

If we’re right that the perception of decline is all about what people experience vs. what they remember, then people should perceive less decline or no decline at all in the years before they were born—after all, they don’t have memories from back then. And indeed, people tell us that the decline in human goodness only began after they arrived on Earth5:

These results can help explain why people find apocalypticism so appealing: to them, it fits the data. If you think that the troubles only started after you exited the birth canal, then “the end is nigh” seems like a reasonable extrapolation of the trend you’ve been observing for your whole life.

We only studied the supposed decline of kindness, but people seem to think that most thing are cratering. For example, in 2017, 59% of Americans said that the lowest point in the nation’s history they could remember is “right now.” People of all ages gave basically the same answer, meaning they thought the disasters of 2017 were worse than World War II, Vietnam, 9/11, Afghanistan, Iraq, etc. Little did they know that the worst was yet to come: in 2024, 67% of Americans said the lowest point in history is, in fact, this very moment. When you feel like you’re constantly hitting new lows, the end of the world isn’t some kind of cold comfort—it’s just the next point on the regression line.

HELP EVERYBODY’S HAIR IS FALLING OUT

If I’m right, people’s colorful theories of the End Times come second. What comes first is the conviction that the world’s problems are brand-spanking-new. And that conviction is stunningly consistent across time.

“Happiness is all gone,” says the Prophecy of Neferty, an Egyptian papyrus from roughly 4000 years ago. “Kindness has vanished and rudeness has descended upon everyone,” agrees Dialogue of a Man with His Spirit, written at around the same time. “It is not like last year […] There is no person free from wrong, and everyone alike is doing it,” says the appropriately-named Complaints of Khakheperraseneb from several hundred years later. And some unknown amount of time after that, the Admonitions of Ipuwer reports that actually things just started going to hell. “All is ruin! Indeed, laughter is perished and no longer made.” Worst of all: “Everyone’s hair has fallen out.”

I could keep going (and I do, in this footnote6), but the point is that when you take a stroll through history, you don’t encounter many people saying things like “the forces of evil and the flaws of human nature have always been among us.” Instead, you meet a lot of people people saying things like “the forces of evil and the flaws of human nature have JUST APPEARED what do we do now??”

That’s still true today. We seem to assume that all the problems in the world arrived only recently, and we do this by default and without realizing it. Notice how people reflexively refer to institutions as “broken” or “rotten,” as if those institutions was once functional and fresh. Regardless of whether crime is going up or going down, people say it’s going up. It’s standard procedure to declare an epidemic of something—loneliness7, misinformation, fighting at schools—without demonstrating that there’s more of it than there used to be. We talk about “late capitalism” as if it just passed its expiration date, when in fact that term is 100 years old.8

“Unlike every previous American generation, we face impossible choices,” wrote David Herbert Donald in a New York Times op-ed. “The age of abundance has ended [...] Consequently, the ‘lessons’ taught by the American past are today not merely irrelevant but dangerous.” Hilariously, Donald published that piece in 1977 when he was...a tenured professor of history at Harvard.

Much more recently, a post went viral on Substack describing how the author came to believe in “the hazy idea of collapse,” which she describes as the “nagging sense that has hung over modern life since 2020, or 2016, or 2008, or 2001 — pick your start date — that things are not working anymore.” Another piece says the quiet part out loud: “We are living through a period of societal collapse. This isn’t a factual statement, but an emotional one.”9

“Hazy” and “emotional” perfectly describe the idea that everything started falling apart sometime in our recent past. We begin with a suspicion of decline and then reason backward from there, cherrypicking data as we go. We all lived through the replication crisis, and so we all know what happens when people have infinite researcher degrees of freedom: they discover that their preexisting biases were right all along.10

GOD’S CRAPPY ESCAPE ROOM

It’s easier to see what this looks like when we’ve got some distance, so here’s an example from long ago. The New England preacher William Miller and his followers were very sure that Jesus was going to return in 1843. This wasn’t some fly-by-night doomsaying; Miller double-checked his calculations for 12 years before he went public, and plenty of educated people saw his reasoning and said, “By jove, you’re right!” They even printed posters showing their work:

If you actually check any of the Bible references behind those numbers, though, they look hella sketchy. God says he will “afflict you for your sins seven times over,” (Lev 26:24) so that means you should...multiply some other number by seven? There’s a passage in the Book of Daniel where a goat’s horn grows really big and takes away “the daily sacrifice from the Lord”; the Millerites assumed this referred the kidnapping of Pope Pius VII in 1798. No offense to our Heavenly Father, but this is the kind of random-ass nonsensical number puzzle I would expect to see in a third-tier escape room.

And yet people found it convincing! The Millerite newspapers were always publishing stories like “Rev. Dimblestick came to our meeting intending to debunk our theories, and instead we out-debated him and he joined our cause.” That’s gotta be because “the world will end in 1843” ultimately sounded pretty plausible. If you encountered the Millerites in the late 1830s or early 1840s, you’d likely agree with them that the world had gone bananas. There’s a rebellion in Rhode Island, riots in Paris, war in Afghanistan, and earthquakes in the Holy Land. Someone just tried to kill a sitting president for the first time ever, and the most recent president dropped dead after only a month in office. The economy is in a panic, states are threatening to secede, thousands of people are dying of cholera, and for goodness’ sake, they’re setting nuns on fire. How could this go on much longer?

So of course Miller’s Biblical research led him to believe that Judgment Day was coming soon. If his number-crunching had spat out the year 2024 instead, he probably would have tweaked his assumptions, because the result would have sounded so ridiculous. No way the world is gonna survive that long!

(The Miller debacle is one of the wildest episodes in American history, and it’s largely been forgotten. For more of the story, see my post from last week: The Day the World Didn’t End.)

That’s why this “hazy” idea of decline is so dangerous—it lowers the standard of evidence for believing miserable things, and raises the standard of evidence for everything else. If you fertilize that pernicious suspicion with a bit of confirmation bias, it can eventually grow into the full-fledged denial that anything has meaningfully changed for the better, that it ever can, and that it ever will.

There’s a lot of people walking around with that conviction calcified in their minds, and if you prod them with any evidence to the contrary—say, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty has shrunk by almost two-thirds in the last 20 years—they’ll doubt the data or explain it away. “Well, maybe those people are a little richer now, but that just means there will be more people burning fossil fuels, and ultimately more casualties of climate change.”

And maybe they’re right! Nobody knows the future, especially not me. But when we’re willing to shrug at a billion people rising out of poverty, if you’ve decided that every bad thing is bad and every good thing is secretly also bad, well, good news! If you read the Bible very closely, it’s clear that God is gonna start raining down hellfire any minute now.

BRING THE CANDLES

I love humans because, God bless us, if you find one of us believing something, you can find someone else who believes the exact opposite of that thing, and with equal fierceness.

So while most folks think we’re heading to hell in a handbasket, there’s a vocal minority who think we’re heading to heaven on an escalator. (Usually, these people are trying to sell you the escalator.) They’re always ready to pop up and tell you things like, “People were worried about coffee and they were wrong, therefore it’s wrong to worry about anything.”

I have less ire to fire at these folks because there are fewer of them, and because doomsaying dominates the discourse—people who tell you to worry seem wise, while people who tell you to relax seem naive. But “Everything is working, turn it all up!” is just as foolish as “Nothing’s working, roll it all back!” because both sides look at the hardest question in the universe and say, “Oh yeah, this one’s easy.”11

Our Problem #1, our Final Boss, our Prime Directive is to multiply the good things and minimize the bad things. Every job, every policy, every idea is grappling with some corollary of that quandary. Right now, our collective efforts produce some mix of making things better and mucking things up. But which ones? How much? Since when? And by what mechanism?

Answering those questions is a huge pain, and I know that because my two lengthiest research projects (1, 2) have tried to answer a tiny subset of them, and both times it led to a yearslong misadventure of untangling extremely annoying issues. How can you pick your sources without biasing your results? Can you trust that the data means what it says? If there’s a kink in the trendline, is that because something happened, or is it because they changed how they were measuring things?

That’s why I pop a cranial artery whenever people assume they already have the answers. It’s like being in a room where something stinks, and everyone is like “Man what stinks” and we’re looking around trying to find the source of the stench then someone enters the room and announces “Have you guys noticed it STINKS in here?” as if we were happily stewing in the stink, waiting for some noble and well-nosed soul to wake us from our slumber.

So when you open your eyes for the first time and see all the depravity and inanity, all the malice and avarice, all the abominations and calamities, and you go “Have you guys notic—” yes! We’ve noticed! If you have a vague feeling that your Bad Cup didn’t used to be so full, and then you conclude we’re slip-sliding toward catastrophe, you haven’t discovered anything. You’ve just taken your biases for a walk.

This story might be half-apocryphal, but apparently on May 19th, 1780, the sky went dark over Connecticut. We don’t know what blotted out the sun—probably some forest fires burning nearby—but the deeply Christian Connecticuters figured it was a sign the End Times had come. At the State House in Hartford, several senators suggested that everybody should return home and prepare to meet their Maker. Amidst the commotion, Senator Abraham Davenport of Stamford stood up and said:

I am against adjournment. The day of judgment is either approaching, or it is not. If it is not, there is no cause for an adjournment; if it is, I choose to be found doing my duty. I wish therefore that candles may be brought.

Candles were brought, and the work continued.

We know this because Columbus was compiling a Book of Prophecies during his travels, which was basically a scrapbook of apocalyptic prophecies plus an unfinished letter to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. In the letter, he says:

I spent six years here at your royal court, disputing the case with so many people of great authority, learned in all the arts. And finally they concluded that it all was in vain, and they lost interest. In spite of that it [the voyage to the Indies] later came to pass as Jesus Christ our Saviour had predicted and as he had previously announced through the mouths of His holy prophets. Therefore, it is to be believed that the same will hold true for this other matter [the voyage to the Holy Sepulchre].

In a more recent survey with more response options, 14% of US Christians said Jesus “definitely” or “probably” will return in their lifetimes, 37% weren’t sure, 25% said that Jesus “definitely” or “probably” will NOT return in their lifetimes, and 22% said he’s not coming back at all, or that they don’t believe in him. I take this to mean that most Christians aren’t sure whether Jesus will return before they die, but if you make them choose (as the other survey did), they lean “yes”.

This is true on average, but it’s not true for every single person or every single memory. Sometimes bad experiences can get even worse over time, and sometimes good things can seem bad in retrospect. But the opposite happens far more often, which is why life is bearable for most people.

If you start with a full Good Cup and and empty-ish Bad Cup, the differential evaporation will lead you to believe that the ratio of good to bad was even better in the past. We think this is exactly what happens when people consider their loved ones instead of the entire world: you mainly perceive good things from your friends and family members, so your Good Cup is usually fuller today than your Bad Cup. Over time, differential evaporation will make that ratio even more positive, leading people to conclude that their loved ones have improved. And indeed, that’s exactly what we found.

By the way, this finding was replicated earlier this year.

Here’s the Talmud, from ~200AD:

If the early generations are characterized as sons of angels, we are the sons of men. And if the early generations are characterized as the sons of men, we are akin to donkeys. And I do not mean that we are akin to either the donkey of Rabbi Ḥanina ben Dosa or the donkey of Rabbi Pinḥas ben Yair, who were both extraordinarily intelligent donkeys; rather, we are akin to other typical donkeys.

Christians agree:

[Martin] Luther once remarked that a whole book could be filled with the signs that happened in his day and that pointed to the approaching end of the world. He thought that the “worst sign” was that human beings had never been so earthly minded “as right now.” Hardly anyone cared about eternal salvation.

In 1627, the English clergyman George Hakewill was so tired of people complaining about the world getting worse over time—an opinion “so generally received, not only among the Vulgar, but of the Learned”—that he wrote a whole book attempting to refute it. He failed, of course. Here’s Nietzche in 1874:

Never was the world more worldly, never poorer in goodness and love. Men of learning are no longer beacons or sanctuaries in the midst of this turmoil of worldliness; they themselves are daily becoming more restless, thoughtless, loveless. Everything bows before the coming barbarism, art and science included.

I got this example from a recent piece in Asterisk Magazine called “The Myth of the Loneliness Epidemic”

Werner Sombart, the guy who coined the term, was thrilled toward the end of his life because he thought capitalism was finally being replaced by a better system called “Nazism.”

If you can’t get enough collapse-related content, there’s an apparently successful Substack called Last Week in Collapse that offers you a “weekly summary of the ongoing collapse of civilization”

If I can play the quote game one last time, these posts sound eerily similar to a New York Times Magazine piece from 1978:

Europeans have a sense of being at the beginning of a downhill slide. [...] There is a pervading sense of crisis, although it has no clear face, as it did in the days of postwar reconstruction. People are disillusioned and preoccupied. The notion of progress, once so stirring, rings hollow now. Nobody can say exactly what he fears, but neither is anyone sanguine about the future. [...] there is a sense that governments no longer have the wisdom or power to cope

This was exactly what it was like to study people’s perception of moral decline. I was basically asking people, “Hey, I’ve spent the past three years working on this question, but could you answer it in .4 seconds?” And their answer was “Sure can.”

You wrote: 'That’s why this “hazy” idea of decline is so dangerous.'

But if, as you show, this idea has been pervasive throughout history, how dangerous can it really be?

Or do you think we might actually be in decline *now* because the hazy idea of decline is more pervasive and more consequential than it was in the past? I.e., have you been caught up in the same tendency for which your article should be a remedy, only at more of a meta level?

No matter how you answer, it was an enjoyable and insightful read, as usual.

Brilliant! That candles be brought indeed!