How to be less awkward

a three-part treatment for a near-universal affliction

Here’s the most replicated finding to come out of my area of psychology in the past decade: most people believe they suffer from a chronic case of awkwardness.

Study after study finds that people expect their conversations to go poorly, when in fact those conversations usually go pretty well. People assign themselves the majority of the blame for any awkward silences that arise, and they believe that they like other people more than other people like them in return. I’ve replicated this effect myself: I once ran a study where participants talked in groups of three, and then they reported/guessed how much each person liked each other person in the conversation. Those participants believed, on average, that they were the least liked person in the trio.

In another study, participants were asked to rate their skills on 20 everyday activities, and they scored themselves as better than average on 19 of them. When it came to cooking, cleaning, shopping, eating, sleeping, reading, etc., participants were like, “Yeah, that’s kinda my thing.” The one exception? “Initiating and sustaining rewarding conversation at a cocktail party, dinner party, or similar social event”.

I find all this heartbreaking, because studies consistently show that the thing that makes humans the happiest is positive relationships with other humans. Awkwardness puts a persistent bit of distance between us and the good life, like being celiac in a world where every dish has a dash of gluten in it.

Even worse, nobody seems to have any solutions, nor any plans for inventing them. If you want to lose weight, buy a house, or take a trip to Tahiti, entire industries are waiting to serve you. If you have diagnosable social anxiety, your insurance might pay for you to take an antidepressant and talk to a therapist. But if you simply want to gain a bit of social grace, you’re pretty much outta luck. It’s as if we all think awkwardness is a kind of moral failing, a choice, or a congenital affliction that suggests you were naughty in a past life—at any rate, unworthy of treatment and undeserving of assistance.

We can do better. And we can start by realizing that, even though we use one word to describe it, awkwardness is not one thing. It’s got layers, like a big, ungainly onion. Three layers, to be exact. So to shrink the onion, you have to peel it from the skin to the pith, adapting your technique as you go, because removing each layer requires its own unique technique.

Before we make our initial incision, I should mention that I’m not the kind of psychologist who treats people. I’m the kind of psychologist who asks people stupid questions and then makes sweeping generalizations about them. You should take everything I say with a heaping teaspoon of salt, which will also come in handy after we’ve sliced the onion and it’s time to sauté it. That disclaimer disclaimed, let’s begin on the outside and work our way in, starting with—

1. THE OUTSIDE LAYER: SOCIAL CLUMSINESS

The outermost layer of the awkward onion is the most noticeable one: awkward people do the wrong thing at the wrong time. You try to make people laugh; you make them cringe instead. You try to compliment them; you creep them out. You open up; you scare them off. Let’s call this social clumsiness.

Being socially clumsy is like being in a role-playing game where your charisma stat is chronically too low and you can’t access the correct dialogue options. And if you understand that reference, I understand why you’re reading this post.

Here’s the bad news: I don’t think there’s a cure for clumsiness. Every human trait is normally distributed, so it’s inevitable that some chunk of humanity is going to have a hard time reading emotional cues and predicting the social outcomes of their actions. I’ve seen high-functioning, socially ham-handed people try to memorize interpersonal rules the same way chess grandmasters memorize openings, but it always comes off stilted and strange. You’ll be like, “Hey, how you doing” and they’re like “ROOK TO E4, KNIGHT TO C11, QUEEN TO G6” and you’re like “uhhh cool man me too”.

Here’s the good news, though: even if you can’t cure social clumsiness, there is a way to manage its symptoms. To show you how, let me tell you a story of a stupid thing I did, and what I should have done instead.

Once, in high school, I was in my bedroom when I saw a girl in my class drive up to the intersection outside my house. It was dark outside and I had the light on, and so when she looked up, she caught me in the mortifying act of, I guess, existing inside my home? This felt excruciatingly embarrassing, for some reason, and so I immediately dropped to the floor, as if I was in a platoon of GIs and someone had just shouted “SNIPER!” But breaking line of sight doesn’t cause someone to unsee you, and so from this girl’s point of view, she had just locked eyes with some dude from school through a window and his response had been to duck and cover. She told her friends about this, and they all made fun of me ruthlessly.

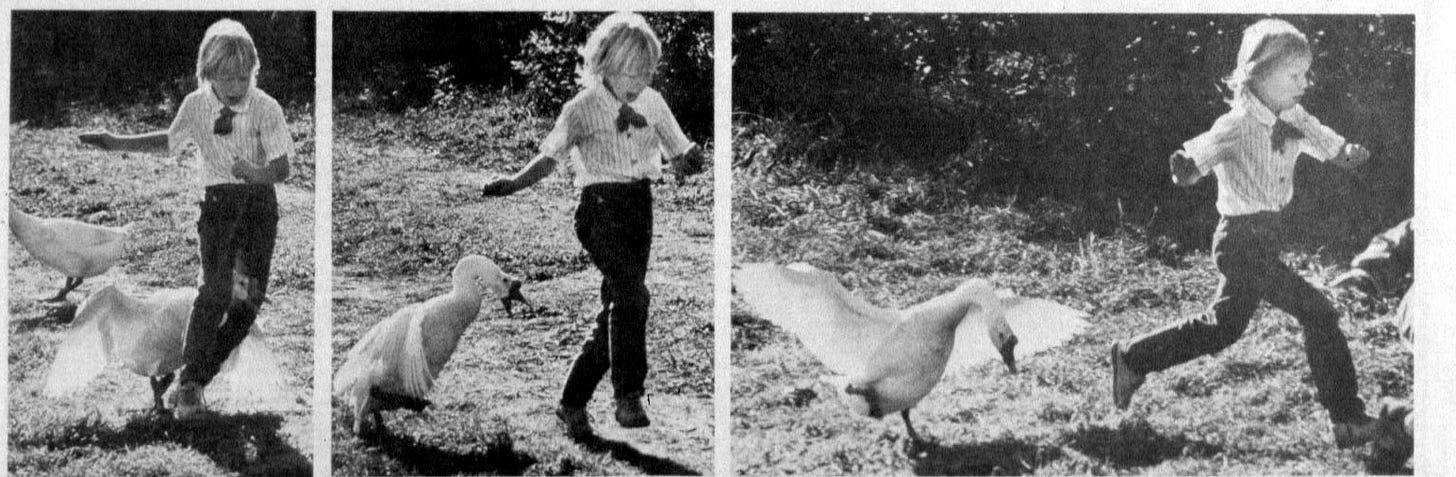

I learned an important lesson that day: when it comes to being awkward, the coverup is always worse than the crime. If you just did something embarrassing mere moments ago, it’s unlikely that you have suddenly become socially omnipotent and that all of your subsequent moves are guaranteed to be prudent and effective. It’s more likely that you’re panicking, and so your next action is going to be even stupider than your last.

And that, I think, is the key to mitigating your social clumsiness: give up on the coverups. When you miss a cue or make a faux pas, you just have to own it. Apologize if necessary, make amends, explain yourself, but do not attempt to undo your blunder with another round of blundering. If you knock over a stack of porcelain plates, don’t try to quickly sweep up the shards before anyone notices; you will merely knock over a shelf of water pitchers.

This turns out to be a surprisingly high-status move, because when you readily admit your mistakes, you imply that you don’t expect to be seriously harmed by them, and this makes you seem intimidating and cool. You know how when a toddler topples over, they’ll immediately look at you to gauge how upset they should be? Adults do that too. Whenever someone does something unexpected, we check their reaction—if they look embarrassed, then whatever they did must be embarrassing. When that person panics, they look like a putz. When they shrug and go, “Classic me!”, they come off as a lovable doof, or even, somehow, a chill, confident person.

In fact, the most successful socially clumsy people I know can manage their mistakes before they even happen. They simply own up to their difficulties and ask people to meet them halfway, saying things like:

Thanks for inviting me over to your house. It’s hard for me to tell when people want to stop hanging out with me, so please just tell me when you’d like me to leave. I won’t be mad. If it’s weird to you, I’m sorry about that. I promise it’s not weird to me.

It takes me a while to trust people who attempt this kind of social maneuver—they can’t be serious, can they? But once I’m convinced they’re earnest, knowing someone’s social deficits feels no different than knowing their dietary restrictions (“Arthur can’t eat artichokes; Maya doesn’t understand sarcasm”), and we get along swimmingly. Such a person is always going to seem a bit like a Martian, but that’s fine, because they are a bit of a Martian, and there’s nothing wrong with being from outer space as long as you’re upfront about it.

2. THE MIDDLE LAYER: EXCESSIVE SELF-AWARENESS

When we describe someone else as awkward, we’re referring to the things they do. But when we describe ourselves as awkward, we’re also referring to this whole awkward world inside our heads, this constant sensation that you’re not slotted in, that you’re being weird, somehow. It’s that nagging thought of “does my sweater look bad” that blossoms into “oh god, everyone is staring at my horrible sweater” and finally arrives at “I need to throw this sweater into a dumpster immediately, preferably with me wearing it”.

This is the second layer of the awkward onion, one that we can call excessive self-awareness. Whether you’re socially clumsy or not, you can certainly worry that you are, and you can try to prevent any gaffes from happening by paying extremely close attention to yourself at all times. This strategy always backfires because it causes a syndrome that athletes call “choking” or “the yips”—that stilted, clunky movement you get when you pay too much attention to something that’s supposed to be done without thinking. As the old poem goes:

A centipede was happy – quite!

Until a toad in fun

Said, “Pray, which leg moves after which?”

This raised her doubts to such a pitch,

She fell exhausted in the ditch

Not knowing how to run.

The solution to excessive self-awareness is to turn your attention outward instead of inward. You cannot out-shout your inner critic; you have to drown it out with another voice entirely. Luckily, there are other voices around you all the time, emanating from other humans. The more you pay attention to what they’re doing and saying, the less attention you have left to lavish on yourself.

You can call this mindfulness if that makes it more useful to you, but I don’t mean it as a sort of droopy-eyed, slack-jawed, I-am-one-with-the-universe state of enlightenment. What I mean is: look around you! Human beings are the most entertaining organisms on the planet. See their strange activities and their odd proclivities, their opinions and their words and their what-have-you. This one is riding a unicycle! That one is picking their nose and hoping no one notices! You’re telling me that you’d rather think about yourself all the time?

Getting out of your own head and into someone else’s can be surprisingly rewarding for all involved. It’s hard to maintain both an internal and an external dialogue simultaneously, and so when your self-focus is going full-blast, your conversations degenerate into a series of false starts (“So...how many cousins do you have?” “Seven.” “Ah, a prime number.”) Meanwhile, the other person stays buttoned up because, well, why would you disrobe for someone who isn’t even looking? Paying attention to a human, on the other hand, is like watering a plant: it makes them bloom. People love it when you listen and respond to them, just like babies love it when they turn a crank and Elmo pops out of a box—oh! The joy of having an effect on the world!

Of course, you might not like everyone that you attend to. When people start blooming in your presence, you’ll discover that some of them make you sneeze, and some of them smell like that kind of plant that gives off the stench of rotten eggs. But this is still progress, because in the Great Hierarchy of Subjective Experiences, annoyance is better than awkwardness—you can walk away from an annoyance, but awkwardness comes with you wherever you go.

It can be helpful to develop a distaste for your own excessive self-focus, and one way to do that is to relabel it as “narcissism”. We usually picture narcissists as people with an inflated sense of self worth, and of course many narcissists are like that. But I contend that there is a negative form of narcissism, one where you pay yourself an extravagant amount of attention that just happens to come in the form of scorn. Ultimately, self-love and self-hate are both forms of self-obsession.

So if you find yourself fixated on your own flaws, perhaps its worth asking: what makes you so worthy of your own attention, even if it’s mainly disapproving? Why should you be the protagonist of every social encounter? If you’re really as bad as you say, why not stop thinking about yourself so much and give someone else a turn?

3. THE INNER LAYER: PEOPLE-PHOBIA

Social clumsiness is the thing that we fear doing, and excessive self-focus is the strategy we use to prevent that fear from becoming real, but neither of them is the fear itself, the fear of being left out, called out, ridiculed, or rejected. “Social anxiety” is already taken, so let’s refer to this center of the awkward onion as people-phobia.

People-phobia is both different from and worse than all other phobias, because the thing that scares the bajeezus out of you is also the thing you love the most. Arachnophobes don’t have to work for, ride buses full of, or go on first dates with spiders. But people-phobes must find a way to survive in a world that’s chockablock with homo sapiens, and so they yo-yo between the torment of trying to approach other people and the agony of trying to avoid them.

At the heart of people-phobia are two big truths and one big lie. The two big truths: our social connections do matter a lot, and social ruptures do cause a lot of pain. Individual humans cannot survive long on their own, and so evolution endowed us with a healthy fear of getting voted off the island. That’s why it hurts so bad to get bullied, dumped, pantsed, and demoted, even though none of those things cause actual tissue damage.1

But here’s the big lie: people-phobes implicitly believe that hurt can never be healed, so it must be avoided at all costs. This fear is misguided because the mind can, in fact, mend itself. Just like we have a physical immune system that repairs injuries to the body, we also have a psychological immune system that repairs injuries to the ego. Black eyes, stubbed toes, and twisted ankles tend to heal themselves on their own, and so do slip-ups, mishaps, and faux pas.

That means you can cure people-phobia the same way you cure any fear—by facing it, feeling it, and forgetting it. That’s the logic behind exposure and response prevention: you sit in the presence of the scary thing without deploying your usual coping mechanisms (scrolling on your phone, fleeing, etc.) and you do this until you get tired of being scared. If you’re an arachnophobe, for instance, you peer at a spider from a safe distance, you wait until your heart rate returns to normal, you take one step closer, and you repeat until you’re so close to the spider that it agrees to officiate your wedding.2

Unfortunately, people-phobia is harder to treat than arachnophobia because people, unlike spiders, cannot be placed in a terrarium and kept safely on the other side of the room. There is no zero-risk social interaction—anyone, at any time, can decide that they don’t like you. That’s why your people-phobia does not go into spontaneous remission from continued contact with humanity: if you don’t confront your fear in a way that ultimately renders it dull, you’re simply stoking the phobia rather than extinguishing it.3

Exposure only works for people-phobia, then, if you’re able to do two things: notch some pleasant interactions and reflect on them afterward. The notching might sound harder than the reflecting, but the evidence suggests it’s actually the other way around. Most people have mostly good interactions most of the time. They just don’t notice.

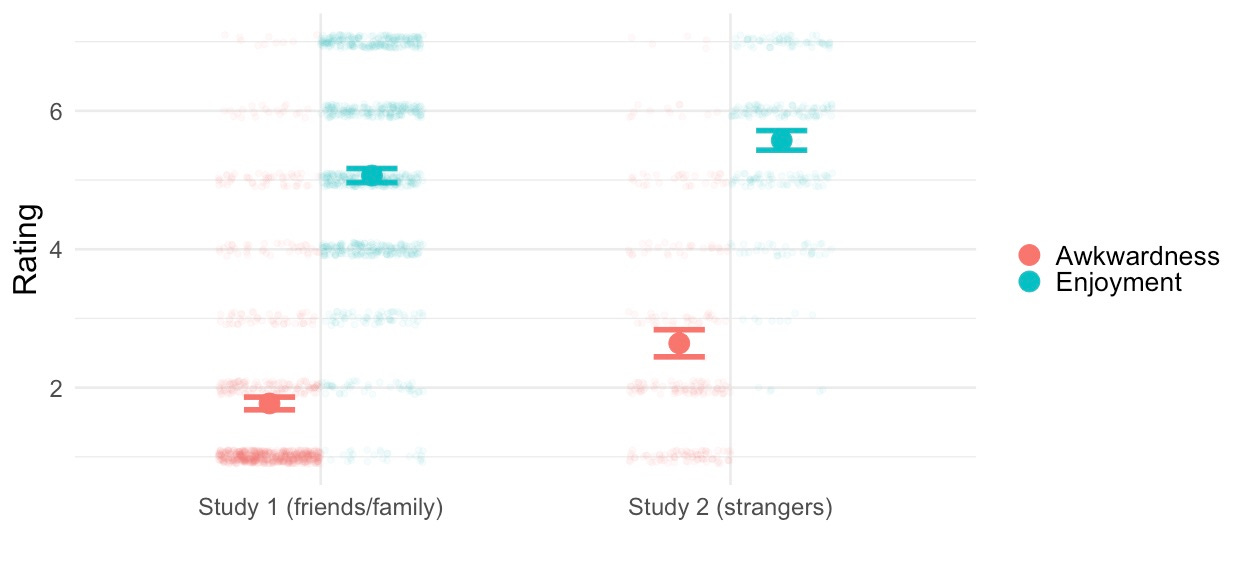

In any study I’ve ever read and in every study I’ve ever conducted myself, when you ask people to report on their conversation right after the fact, they go, “Oh, it was pretty good!”. In one study, I put strangers in an empty room and told them to talk about whatever they want for as long as they want, which sounds like the social equivalent of being told to go walk on hot coals or stick needles in your eyes. And yet, surprisingly, most of those participants reported having a perfectly enjoyable, not-very-awkward time. When I asked another group of participants to think back to their most recent conversation (which were overwhelmingly with friends and family, rather than strangers), I found the same pattern of results4:

But when you ask people to predict their next conversation, they suddenly change their tune. I had another group of participants guess how this whole “meet a stranger in the lab, have an open-ended conversation” thing would go, and they were not optimistic. Participants estimated that only 50% of conversations would make it past five minutes (actually, 87% did), and that only 15% of conversations would go all the way to the time limit of 45 minutes (actually, 31% did). So when people meet someone new, they go, “that was pretty good!”, but when they imagine meeting someone new, they go, “that will be pretty bad!”

A first-line remedy for people-phobia, then, is to rub your nose in the pleasantness of your everyday interactions. If you’re afraid that your goof-ups will doom you to a lifetime of solitude and then that just...doesn’t happen, perhaps it’s worth reflecting on that fact until your expectations update to match your experiences. Do that enough, and maybe your worries will start to appear not only false, but also tedious. However, if reflecting on the contents of your conversations makes you feel like that guy in Indiana Jones who gets his face melted off when he looks directly at the Ark of the Covenant, then I’m afraid you’re going to need bigger guns than can fit into a blog post.

GOODNIGHT AND GOOD DUCK

Obviously, I don’t think you can instantly de-awkward yourself by reading the right words in the right order. We’re trying to override automatic responses and perform laser removal on burned-in fears—this stuff takes time.

In the meantime, though, there’s something all of us can do right away: we can disarm. The greatest delusion of the awkward person is that they can never harm someone else; they can only be harmed. But every social hangup we have was hung there by someone else, probably by someone who didn’t realize they were hanging it, maybe by someone who didn’t even realize they were capable of such a thing. When Todd Posner told me in college that I have a big nose, did he realize he was giving me a lifelong complex? No, he probably went right back to thinking about his own embarrassingly girthy neck, which, combined with his penchant for wearing suits, caused people to refer to him behind his back as “Business Frog” (a fact I kept nobly to myself).

So even if you can’t rid yourself of your own awkward onion, you can at least refrain from fertilizing anyone else’s. This requires some virtuous sacrifice, because the most tempting way to cope with awkwardness is to pass it on—if you’re pointing and laughing at someone else, it’s hard for anyone to point and laugh at you. But every time you accept the opportunity to be cruel, you increase the ambient level of cruelty in the world, which makes all of us more likely to end up on the wrong end of a pointed finger.

All of that is to say: if you happen to stop at an intersection and you look up and see someone you know just standing there inside his house he immediately ducks out of sight, you can think to yourself, “There are many reasonable explanations for such behavior—perhaps he just saw a dime on the floor and bent down to get it!” and you can forget about the whole ordeal and, most importantly, keep your damn eyes on the road.

PS: This post pairs well with Good Conversations Have Lots of Doorknobs.

Psychologists who study social exclusion love to use this horrible experimental procedure called “Cyberball”, where you play a game of virtual catch with two other participants. Everything goes normally at first, but then the other participants inexplicably start throwing the ball only to each other, excluding you entirely. (In reality, there are no other participants; this is all pre-programmed.) When you do this to someone who’s in an fMRI scanner, you can see that getting ignored in Cyberball lights up the same part of the brain that processes physical pain. But you don’t need a big magnet to find this effect: just watching the little avatars ignore you while tossing the ball back and forth between them will immediately make you feel awful.

My PhD cohort included some clinical psychologists who interned at an OCD treatment center as part of their training. Some patients there had extreme fears about wanting to harm other people—they didn’t actually want to hurt anybody, but they were afraid that they did. So part of their treatment was being given the opportunity to cause harm, and to realize that they weren’t really going to do it. At the final stage of this treatment, patients are given a knife and told to hold it at their therapist’s throat, who says, “See? Nothing bad is happening.” Apparently this procedure is super effective and no one at the clinic had ever been harmed doing it, but please do not try this at home.

As this Reddit thread so poetically puts it, “you have to do exposure therapy right otherwise you’re not doing exposure therapy, you’re doing trauma.”

You might notice that while awkwardness ratings are higher when people talk to strangers vs. loved ones, enjoyment ratings are higher too. What gives? One possibility is that people are “on” when they meet someone new, and that’s a surprisingly enjoyable state to be in. That’s consistent with this study from 2010, which found that:

Participants actually had a better time talking to a stranger than they did talking to their romantic partner.

When they were told to “try to make a good impression” while talking to their romantic partner (“Don’t role-play, or pretend you are somewhere where you are not, but simply try to put your best face forward”), they had a better time than when they were given no such instructions.

Participants failed to predict both of these effects.

Like most psychology studies published around this time, the sample sizes and effects are not huge, so I wouldn’t be surprised if you re-ran this study and found no effect. But even if people enjoyed talking to strangers as much as they enjoy talking to their boyfriends and girlfriends, that would still be pretty surprising.

My brother struggled with social awkwardness when he was younger -- his solution, as you suggest, was to randomly lie down in public places, drop food in grocery stores, and otherwise embarrass himself in ways that proved to be totally inconsequential after the brief moment of shame. It worked; he's now extraordinarily charismatic. It's important to talk to the spiders!

As always, so many excellent points in this one. "But every time you accept the opportunity to be cruel, you increase the ambient level of cruelty in the world, which makes all of us more likely to end up on the wrong end of a pointed finger." might be my favorite part.