The Anarchist and the Hockey Stick

OR: "The Inquisition was right"

Even a years ago, if you had tried to talk to me about the “philosophy of science,” I would have skeddadled. Philosophy? As in, people just...saying stuff? No thanks dude, I’m good. I’m a Science Guy, I talk Data.

But then I realized something: I had no idea what I was doing. Like, nobody had ever told me what science was or how to do it. My advisor never sat me down and gave me the scientific Birds and the Bees talk (“When a hypothesis and an experiment love each other very much...”). I just showed up to my PhD and started running experiments. Wasn’t I supposed to be using the Scientific Method, or something? Come to think of it, what is the Scientific Method?

As far as I could tell, everybody else was as clueless as me. There are no classes called “Coming Up with Ideas 101” or “How to Pick a Project When There Are Literally Infinite Projects You Could Pick.” We all learned through osmosis—you read some papers, you watch some talks, and then you just kinda wing it.

We’re devoting whole lifetimes to this project—not to mention billions of taxpayer dollars—so shouldn’t we, you know, have some idea of what we’re doing? Fortunately, in the 20th century, three philosophers were like, “Damn, this science thing is getting pretty crazy, we should figure out what it is and what it’s all about.”1

Karl Popper said: science happens by proposing hypotheses and then falsifying them.

Thomas Kuhn said: science happens by people trying to solve puzzles in the prevailing paradigm and then shifting the paradigm entirely when things don’t add up.

And Paul Feyerabend said: *BIG WET FART NOISE*

Guess whose book I’m gonna tell you about?

THE INQUISITION WAS RIGHT

Here’s how Feyerabend put it in Against Method (1975, emphasis his):

The thesis is: the events, procedures and results that constitute the sciences have no common structure; there are no elements that occur in every scientific investigation but are missing elsewhere. [...] Successful research does not obey general standards; it relies now on one trick, now on another [...] This liberal practice, I repeat, is not just a fact of the history of science. It is both reasonable and absolutely necessary for the growth of knowledge.

Which is to say: there is no such thing as the scientific method. Feyerabend’s famous dictum is “anything goes,” which he explained is “the terrified exclamation of the rationalist who takes a closer look at history.”2 Whenever you try to lay down some rule like “science works like this,” Feyerabend pop ups and says “Aha! Here’s a time when someone did exactly the opposite of that, and it worked!”

Here’s an example. Say some guy named Galileo comes up to you and says something crazy like, “The Earth is constantly moving.” Well, Rule #1 of science is supposed to be “theories should fit the facts,” so you, a dutiful scientist, consult them:

When you’re on something that’s moving (like a horse or a cart), you notice it for all sorts of reasons. You feel the wind, you see the scenery changing, you might get a little sick, and so on. If the Earth was moving, we’d know it.

When you jump straight up, you land on exactly the point where you started. If the Earth was moving, that wouldn’t happen—it would change position while you’re in the air, and your landing spot would be different from your launching spot.

The Earth does actually move sometimes; it’s called an earthquake. And when that happens, buildings topple over, you get mudslides and avalanches, etc. So the Earth can’t be moving all the time, or else those things would be happening all the time, too.

Those facts seem pretty irrefutable, so you conclude the Earth does not move. Unfortunately, it does move, and you’re not going to figure that out by being a scientific goody-two-shoes. Instead, you’ll have to entertain the possibility that this Galileo guy might be right. In Feyerabend’s words:

Turning the argument around, we first assert the motion of the earth and then inquire what changes will remove the contradiction. Such an inquiry may take considerable time, and there is a good sense in which it is not finished even today. The contradiction may stay with us for decades or even centuries. Still, it must be upheld until we have finished our examination or else the examination, the attempt to discover the antediluvian components of our knowledge, cannot even start. This, we have seen, is one of the reasons one can give for retaining, and, perhaps, even for inventing, theories which are inconsistent with the facts.

To Feyerabend, our minds are like deep lakes, our assumptions are like the fish you can’t see from the surface, and a wacko theory is like a stick of dynamite that you drop into the water so it blows up and all the dead assumptions float to the surface. If you take Galileo’s dumb-sounding theory seriously, you start wondering whether your facts are as irrefutable as they seem: Would you really be able to tell if the Earth and everything on it was moving? For instance, if you were below deck on a ship, would you be able to tell whether the ship was docked or sailing smoothly? Have you ever even checked?

Feyerabend goes so far as to claim that, in the whole Galileo debacle, the Catholic Church was the side “trusting the science.” The Inquisition didn’t just condemn Galileo for contradicting the Bible. They also said he was wrong on the facts. That part of their judgment “was made without reference to the faith, or to Church doctrine, but was based exclusively on the scientific situation of the time. It was shared by many outstanding scientists — and it was correct when based on the facts, the theories and the standards of the time.” As in: the Inquisition was right.

THE ANARCHIST

Feyerabend described himself as an “epistemological anarchist,” and other people have called him that too, but they meant it as an insult. This whole “anything goes” thing causes a lot of pearl-clutching and handwringing about misinformation and pseudoscience. There’s supposed to be some kind of Special Secret Science Sauce that makes “real” science good, and if it turns out that you can squirt any kind of condiment on there and it tastes fine, then why are we spending so much on the brand-name stuff?

I think the pearl-clutchers are onto something here, and I’ll come back to that in a second. But first, even if the strong version of Feyerabend’s thesis makes people faint, those same people probably agree with him when it comes to revolutionary science. A breakthrough, almost by definition, has to be at least a little ridiculous—otherwise, someone would have made it already. For example, when you look back at the three most important breakthroughs in biology in the last forty years, every one of them required at least one step, and sometimes many steps, that sounded stupid to a lot of people:

We have mRNA vaccines because one woman was so sure she she could make the technology work that she kept going for decades, even when all of her grants were denied, her university tried to kick her out, and her advisor tried to deport her.

We have CRISPR in part because some scientists at a dairy company were trying to make yogurt.

We have polymerase chain reaction because one guy wanted to “find out what kind of weird critters might be living in boiling water in Yellowstone” and another guy refused to listen to his friends when they told him he was wasting his time: “...not one of my friends or colleagues would get excited over the potential for such a process. [...] most everyone who could take a moment to talk about it with me, felt compelled to come up with some reason why it wouldn’t work.”3

(That’s why it’s always a con whenever people dig up silly-sounding studies to prove that the government is wasting money on science. They’ll be like “Can you believe they’re PAYING PEOPLE to SCOOP OUT PART OF A CAT’S BRAIN and then SEE IF IT CAN STILL WALK ON A TREADMILL???” And then it turns out the research is about how to help people walk again after they have a spinal cord injury. A lot of research is bad, but the goofiness of its one-sentence summary is not a good indication of its quality.4)

Not only do we have useful research that breaks the rules; we also have useless research that follows the rules. You can develop theories, run experiments, gather data, analyze your results, and reject your null hypotheses, all by the book, without a lick of fraud or fakery, and still not produce any useful knowledge. In psychology, we do this all the time.

PROGRESS DEPENDS ON FRAUD

Everybody seems to agree with these facts in the abstract, but we clearly don’t believe them in our hearts, because we’ve built a scientific system that denies them entirely. We hire people, accept papers, and dole out money based on the assumption that science progresses by a series of sensible steps that can all be approved by committee. That’s why everyone tries to pretend this is happening even when it isn’t.

For example, the National Institutes of Health don’t like funding anything risky, so a good way to get money from them is to show them some “promising” and “preliminary” results from a project that, secretly, you’ve already completed. When they give you a grant, you can publish the rest of the results and go “wow look it all turned out so well!” when actually you’ve been using the money to try other stuff, hopefully generating “promising” and “preliminary” results for the next grant application. Which is to say, a big part of our scientific progress depends on defrauding the government.

In fact, whenever we find ourselves stuck on some scientific problem for a long time, it’s often from an excess of being reasonable. For instance, we don’t have any good treatments for Alzheimer’s in large part because a “cabal” of researchers was so sure they knew which direction Alzheimer’s science should take that they scuttled anybody trying to follow other leads. Their favored hypothesis—that a buildup of amyloid proteins gums up the brain—enjoyed broad consensus at the time, and anybody who harbored doubts looked like a science-denier. Decades and billions of dollars later, the amyloid hypothesis is pretty much kaput, and we’re not much closer to a cure, or even an effective treatment. So when Grandma starts getting forgetful and there’s nothing you can do about it, you should blame the people who enforced the supposed rules of science, not the people who tried to break them.

Likewise, even if we believe that science requires occasional irrationality, we hide this fact from our children. Walk into an elementary classroom and you’ll probably see a poster like this:

Most of the things my teachers hung on the walls turned out to be whoppers: the food pyramid is not a reasonable dieting guide, Greenland is actually one-seventh the size of South America (despite how it looks on the map), and Maya Angelou never said that thing about people remembering how you made them feel. But this hokum about the “scientific method” is the tallest tale of them all.

Yes, scientists do all of these things sometimes, but laying out these steps as “the” method implies that science is a solved problem, that everybody knows what’s going on, that we all just show up and paint by numbers, and that you, too, can follow the recipe and discoveries will pop out the other end. (“Hey pal, I’m stuck—what comes after research again?”) This “method” is about as useful as my friend Steve’s one-step recipe for poundcake, which goes: “Step 1: add poundcake.”5

THAT NOTED NUISANCE, WORLD WAR II

I read Against Method because people kept recommending it to me, and now I see why. Ol’ Paul and I have a similar vibe: we both love italics and hate hierarchy. But I have two bones to pick with him.

First, Feyerabend has a bit of a Nazi problem—namely, that he was a Nazi. He mentions this in a bizarre footnote toward the end of the book:

Like many people of my generation I was involved in the Second World War. This event had little influence on my thinking. For me the war was a nuisance, not a moral problem.

When he was drafted, his main reaction was annoyance that he couldn’t continue studying astronomy, acting, and singing:

How inconvenient, I thought. Why the hell should I participate in the war games of a bunch of idiots? How do I get out of it? Various attempts misfired and I became a soldier.

He did a bit more than that. According to his entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Feyerabend earned the Iron Cross for gallantry in battle, and was promoted to lieutenant by the end of the war. He later quipped that he “relished the role of army officer no more than he later did that of university professor,” which is, uh, not the most reassuring thing one can say about either of those jobs. (“Don’t worry, students! I was indeed an officer in the Wermacht, but I hated it just as much as I hate teaching you.”)6

Look, I don’t think you should judge people’s ideas by judging their character.7 I expect everyone I read to have a thick file of foibles, and most of the folks who have something to teach me probably don’t share my values. But there are “foibles” and then there’s “carrying a gun for Hitler and then being extremely nonchalant about it.” That’s especially weird for a philosopher, since thinking critically about stuff is his job.

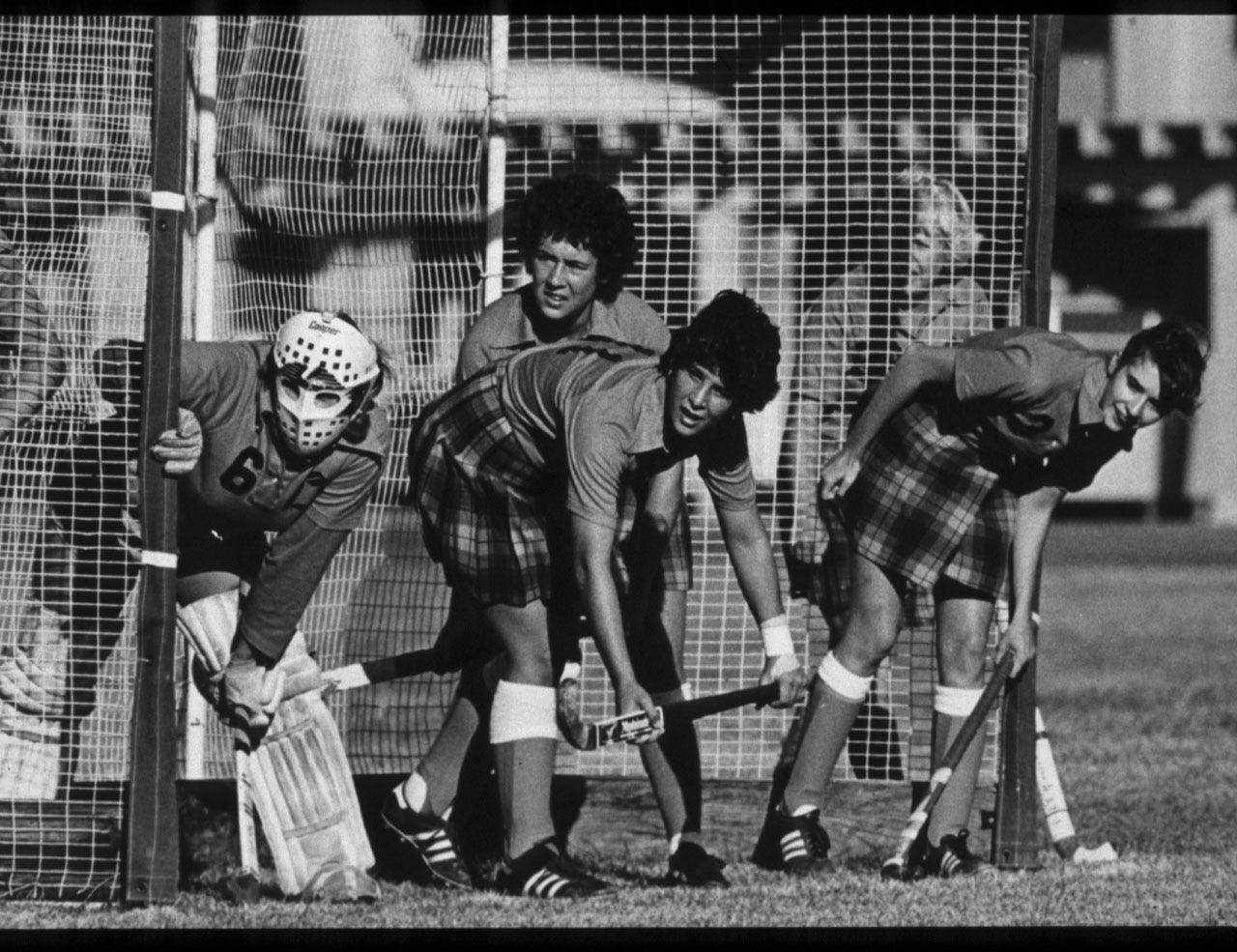

THE HOCKEY STICK

So me and Herr Feyerabend may not see eye-to-eye vis-a-vis WWII, but my biggest philosophical gripe with him is that he doesn’t seem to care about the Hockey Stick:

The Hockey Stick is the greatest mystery in human history. Something big happened in the past ~400 years, something that never happened before in the ~300,000 years of our species’ existence. People have all sorts of theories about what caused the Hockey Stick, but everyone agrees that science played a part. We started investigating the mysteries of the universe in a new way, and our discoveries piled up and spilled over into technology much faster than they ever had before.

So, fine, “anything goes,” but some things go better than others. That’s why I don’t buy Feyerabend’s claim that the scientific method doesn’t exist. I think it doesn’t exist yet. That is, we’ve somehow succeeded in the practice of science without understanding it in principle. Although we haven’t solved the Mystery of the Hockey Stick, there are too many bodies to deny the mystery exists (the bodies in this mystery are alive—that’s the whole point).

Even though Feyerabend denies that mystery, perhaps he can help us solve it. That first upward tick of the Hockey Stick, that almost imperceptible liftoff sometime after the year 1600—that was a burst of Feyerabendian irrationality. The first scientists did something pretty stupid for the time: they ditched the books that had taught people for thousands of years (some of them supposedly written by God) and decided to do things themselves. They claimed you could discover objective, useful truths if you built air-pumps and peered through prisms, and they were...mostly wrong. It took ~200 years for this promise to really start paying off, which is why we only reached the crook of the Hockey Stick sometime after 1800.

So for two centuries, the progenitors of modern science mainly made fools of themselves. Early on, a popular play called The Virtuoso ridiculed the Royal Society (the organization that housed most of the important early scientists) by depicting some of their actual experiments on stage—a buffoonish natural philosopher tries to “swim on dry land by imitating a frog” and transfuses sheep’s blood into a man, causing a tail to grow out of the man’s butt. A few decades later, the politician Sir William Temple claimed that no material benefits had come from the “airy Speculations of those, who have passed for the great Advancers of Knowledge and Learning.” And fifty years after that, the writer Samuel Johnson looked upon the works of science and judged them to be “meh”:

When the Philosophers of the last age were first congregated into the Royal Society, great expectations were raised of the sudden progress of useful arts [...] The society met and parted without any visible diminution of the miseries of life.

THE RACCOON WILL SEE YOU NOW

Every new scientific investigation must trace this same path. You must first estrange yourself from the old ways of thinking, and then you must fall in love with new ways of thinking, and you must do both of these things before they are reasonable. Whatever the real scientific method is, these must be the first two steps. Incumbent theories are always going to be stronger than their younger challengers—at first. Only the truly foolish will be able to discover the evidence that ultimately overturns the old and establishes the new.

But this isn’t a general purpose, broad spectrum foolishness. It’s a laser-targeted, precise kind of foolishness. Falling in love with a fledgling idea is fine, but eventually you have to produce better experiments and more convincing explanations than the establishment can muster, or else your theory is going to go where 99% of them go, which is nowhere. And this is where the rules do matter. We remember Galileo because his arguments, as weird as they were at the time, ultimately held up.8 We would not remember him if he tried to claim that the Earth turns on its axis because there’s a sort of cosmic Kareem Abdul-Jabbar spinning it on his fingertip like a basketball.9

People call it “Nobel Disease” when scientist-laureates do nutty things like talk to imaginary fluorescent raccoons, as if this nuttiness is a tax on the scientists’ talent. But that’s backwards: that nuttiness is part of their talent. The craziness it takes to talk to the raccoons is the same craziness it takes to try creating a polymerase chain reaction when everybody tells you it won’t work. It’s just an extremely specific and rare kind of craziness. You have to grasp reality firmly enough to understand it, but loosely enough to let it speak. Which is to say, our posters of the “Scientific Method” should look like this:

FAREWELL TO REASON

Back in 2011, a psychologist named Daryl Bem published a bunch of studies claiming to show that ESP is real. This helped jumpstart the replication crisis in psychology, and some folks wonder whether that was Bem’s intention all along—maybe his wack-a-doo experiments were a false flag operation meant to expose the weakness of our methods.

I don’t think that’s true of Bem, but it might well be true of Feyerabend. Against Method is a medium-is-the-message kind of book: it’s meant to induce the same kind of madness that Feyerabend claims is necessary for scientific progress. That’s why he praises voodoo and astrology, that’s why he spends a whole chapter doing a non-sequitur close-reading of Homer10, and that’s even why he mentions his blasé attitude toward his Nazi days—he wants to upset you. He’s trying to pull a Galileo, to make an argument that’s obviously at odds with the facts, trying to trick you into looking closer at those facts so that you’ll see they’re shakier than you thought. He wants you to clutch your pearls because he knows they’ll crumble to dust in your hands.

This is the guy who once exclaimed in an interview, “I have no position! [...] I have opinions that I defend rather vigorously, and then I find out how silly they are, and I give them up!”11 He’s a stick of dynamite—you toss him into your mind so you can see what floats to the surface. And once the waves subside and the quiet returns, perhaps then you will hear the voice of the fluorescent raccoon, and perhaps you will listen.

Obviously there were more, but people mainly talk about these three. Sometimes they mention a fourth guy named Imre Lakatos, but he comes up less often, probably because he died tragically early. (In fact, he was supposed to write a book rebutting Feyerabend, which was going to be called For Method.) If you’re a philosopher, it behooves you to live a long time so people have plenty of opportunities to yell at you, thereby increasing your power. That’s why, personally, I don’t plan to die.

Here, “rationalist” refers to Feyerabend’s nemeses: Popper and his ilk, who thought that science required playing by the rules. It does not refer to the online movement of people trying to think correctly.

If you wanna get really sad, read the entirety of Kary Mullis’ Nobel lecture, which traces the development of PCR alongside the disintegration of his relationship. Here’s how it ends:

In Berkeley it drizzles in the winter. Avocados ripen at odd times and the tree in Fred’s front yard was wet and sagging from a load of fruit. I was sagging as I walked out to my little silver Honda Civic, which never failed to start. Neither Fred, empty Becks bottles, nor the sweet smell of the dawn of the age of PCR could replace Jenny. I was lonesome.

I got this example from this recent piece by Stuart Buck.

A couple weeks ago, I was on a conference panel with someone who predicted that AI will replace human scientists within 5-10 years. I disagreed, and this is exactly why. LLMs work because we can train them on a couple quintillion well-formed sentences. We’ve got way less well-formed science, and we have a hard time telling the well-formed from the malformed.

Feyerabend isn’t alone here—20th-century philosophers of science have an alarmingly high body count. Lakatos (see footnote above) allegedly forced a 19-year-old Jewish girl to commit suicide during WWII because he was too afraid to help her hide from the Nazis. I don’t think Popper or Kuhn ever killed anybody, although Kuhn once threw an ashtray at the filmmaker Errol Morris, who then wrote a book about it.

I do think serving in the Nazi army should disqualify you from becoming, say, the pope, but I understand that some people disagree about this.

Except for his cockamamie theory of the tides. Nobody wins ‘em all!

I sometimes get emails from folks who want to sell me on a theory of everything, assuming that I’ll be a sympathetic audience since I’m always going on about crazy ideas in science. And sure, I’ll bend my ear for a dotty hypothesis. But if you want me not just to listen, but to believe, then you’ll have to bring data. To be fair, though, I’ll give anybody the same benefit of the doubt that the original scientists got—that is, I’ll withhold judgment for two centuries.

This will be interesting to like, four people, but I’ve gotta let those four people know: one of the final chapters of Against Method makes a stunningly similar argument to Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, which is that ancient humans weren’t conscious in the way modern humans are, but instead experienced consciousness as the voice of the gods. Here’s what Feyerabend says when discussing Homer:

Actions are initiated not by an “autonomous I” but by further actions, events, occurrences, including divine interference. And this is precisely how mental events are experienced. [...] Archaic man lacks “physical” unity, his “body” consists of a multitude of parts, limbs, surfaces, connections; and he lacks “mental” unity, his “mind” is composed of a variety of events, some of them not even “mental” in our sense, which either inhabit the body-puppet as additional constituents or are brought into it from outside.

This is super weird, because Against Method came out one year before Origin of Consciousness. Did Feyerabend and Jaynes know each other, or was this the zeitgeist speaking through both of them? I have no idea, and I haven’t seen anybody comment on the connection except for this one guy on Goodreads.

This interview is also notable for the fact that Feyerabend predicts the journalist’s divorce 17 years in advance.

Extremely disappointing in an otherwise fine article to see Feyerabend slandered as a Nazi or "carrying a gun for Hitler". In point of fact, he was not a Nazi (what part of Feyerabend's personality strikes you as compatible with as totalizing an ideology as Nazism?). Rather, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht (the regular German army, not a Nazi institution like the SS) along with practically every other German or Austrian man at the time. To describe his service in the war as "carrying a gun for Hitler" would be a bit like describing you as having "voluntarily paid taxes to the US government [which did this or that horrible thing]" or having "signed a statement saying it would be just fine with you if USG conscripted you into any hypothetical future war, just so you could receive federal student aid."

The worst that could be said about Feyerabend in that regard is that he failed to make himself into a Sophie Scholl, a Claus von Stauffenberg or a Dietrich Bonhoeffer. But the thing about exemplary moral courage is that it is rare, and accordingly tawdry to criticize others for their lack of it in circumstances that one has never, oneself, had to face.

The Eastern Front was one of the most horrible episodes in human history, and it left Feyerabend-- who never signed up for it and in fact tried unsuccessfully to get out of it--permanently disabled and in chronic pain for the rest of his life. I don't think I'm in any position to decide whether he later talked about it in a way that was nice enough to suit my taste.

I fear writing what I am about to say because it feels transgressive to acknowledge the value of a scientific wild hair up someone's ass as the source of inspiration for true "scientific" change. But I believe it to be true. I have spent almost 40 years learning, reviewing or implementing some form of "scientific" discovery -- and the process you describe is exactly right. The characterization of the NIH in particular is quite apt. Does it mean that we destroy the infrastructure that is an outgrowth of an illusion -- well, the hockey stick (and its twin that depicts historical changes in life expectancy) suggest something is working. So maybe not destroy the infrastructure but loosen some parameters so that we catch that wild hair a bit sooner? I appreciate the disquiet in embracing someone who was comfortable being a Nazi but perhaps this is an accident of history -- I have known many scientists famous or otherwise -- whose moral fabric has only a fragile connection to morality as we commonly view it. It is a common fallacy that science is a noble calling populated only by the self-sacrificing. Thank you for the clear and entertaining writing about what most people trained or practicing "science" know to be true.