Is psychology going to Cincinnati?

OR: The mystery of the televised salad

There’s a thought that’s haunted me for years: we’re doing all this research in psychology, but are we learning anything? We run these studies and publish these papers and…then what? The stack of papers just gets taller?

This worries me because I want to contribute to the grand project of understanding the mind, but I’m not sure how to do that. What’s the point of tossing another paper on the pile when it’s not clear that the last 100 papers added anything? Running studies can be a pain in the butt, so I’d like to do work that matters, not just work that gets a gold star goes up on the fridge (“Good job, lil buddy! You did so much psychology today!”).

That’s why I’ve returned to these questions again and again and again. But I’ve never come up with satisfying answers, and now I finally understand why.

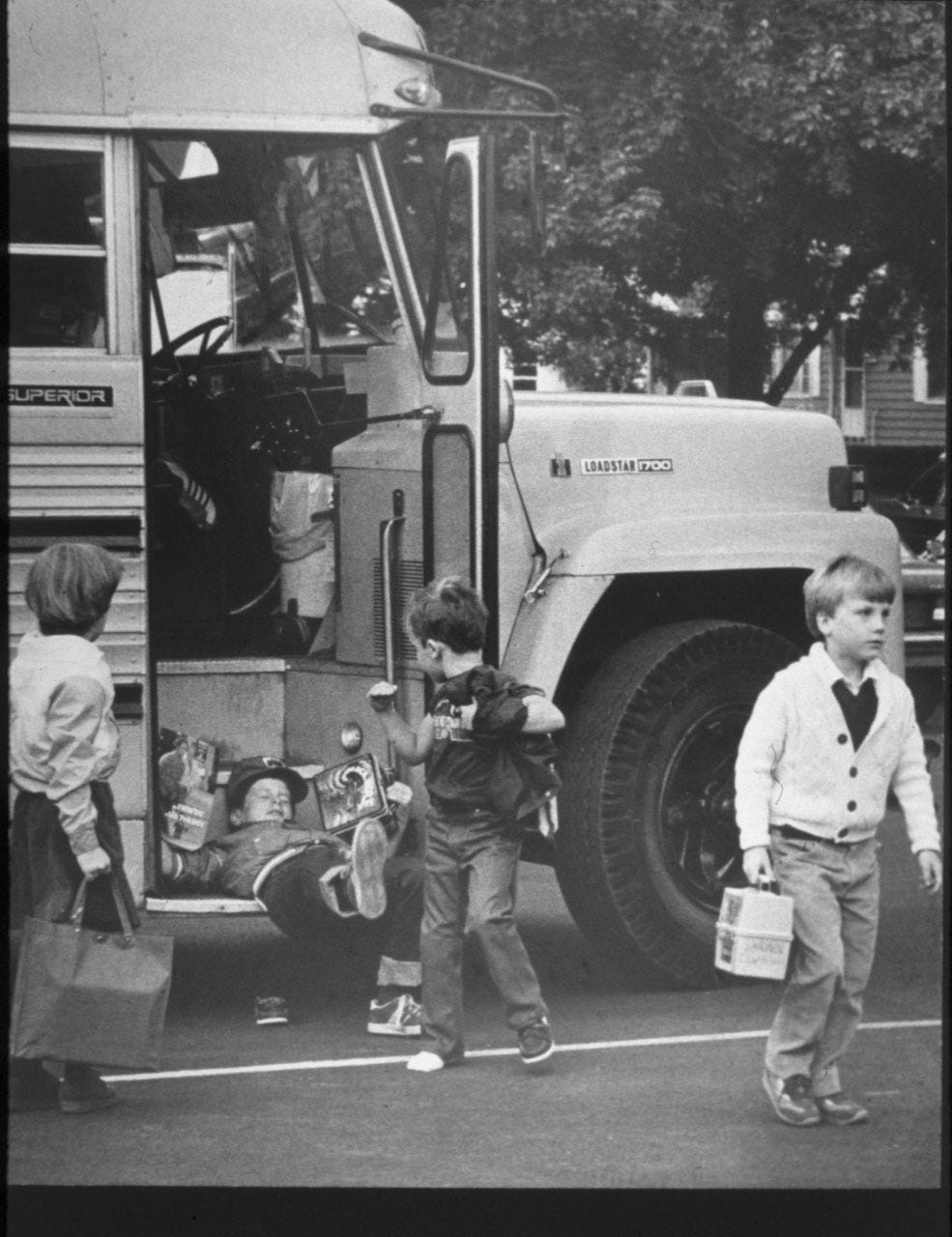

I’ve got this picture in my head: we’re all on a bus that’s supposedly going to Cincinnati. But there are no road signs and we don’t have a GPS, so we have no idea if we’re going in the right direction. We can’t measure our progress by how much gas we’re burning, or whether we’ve upgraded from a manual transmission to an automatic, or whether the government bought us a new bus. And you can’t just look out the window and go, “I dunno, kinda feels like we’re headed toward Arkansas,” which, I realize now, is what I’ve been doing so far.

Instead, you first gotta ask: how could we know we’re getting closer to Cincinnati?

In my estimation, there are five ways to measure psychology’s progress, and we are succeeding in exactly one of them.

1. WE’VE DONE A GREAT JOB OVERTURNING OUR INTUITIONS, THUMBS UP ALL AROUND

In order to survive, every human needs to have some model of the world: how their body functions, how animals behave, how matter moves, etc. Psychologists call these “folk” theories—folk physics, folk biology, folk economics, and so on—the kind of explanations you might come up with if you just kinda bumble around, explanations that are good enough to keep you alive, but often go wrong. One way that science can make progress, then, is by finding the places where our folk theories miss the mark.

Psychology has done this really well. In fact, I’m gonna go out on a limb here: I think pretty much all progress in psychology can be summed up as “overturning intuitions.”

You see this right away when you look at lists of our field’s classic works (after deleting all the stuff that doesn’t replicate). They’re all stories about how you think people would or should do one thing, but then they do another thing instead: the Milgram shock studies1, the pantheon of cognitive biases, those extremely cute studies where children think they can violate the laws of physics, etc.

Everything I’ve ever listed as an “underrated idea in psychology” (vol I, vol II) also falls into this category. Ditto for the things on this list of major recent discoveries assembled by the psychologist Paul Bloom.

I think this work is wonderful. It’s why I became a psychologist in the first place. I got my mind blown over and over again—you’re telling me that when something bad happens to me, I’ll probably recover faster than I expect? That I don’t actually understand how a bicycle works? That I have a bunch of vivid but false memories in my head, like the Monopoly Man wearing a monocle? Of course I wanted to get in on that!

Everything I’ve done since then has fit the same mythbusting mold: the illusion of moral decline, widespread misperceptions of long-term attitude change, do conversations end when people want them to, the liking gap—all of those studies involved fact-checking people’s folk psychology.

We’re in good company here, because this is how other fields got their start. Galileo spent a lot of time trying to overturn folk physics: “I know it seems like the Earth is standing still, but it’s actually moving.” And early biologists like Francesco Redi spent a lot of time trying to overturn folk biology: “I know it seems like bugs come from rotting meat, but bugs actually come from other bugs.” (“Also, you can’t turn basil into scorpions.”)

There’s still plenty to be done in this vein. Our folk psychology is a thick tangle of erroneous assumptions; surely there are a few weeds left. And we might find them faster if we were explicit about that goal. I spent so many hours alone in my office being like, “What am I actually doing?”, and I would have gotten more done if I had been like, “Oh, my job is to put folk psychology to the test.” That’s not a guarantee—there’s still an art to picking the right intuitions and the appropriate tests, but it’s easier to do art when you don’t have to first invent the idea of a paintbrush.

2. UNFORTUNATELY, WE’RE STILL LOSING TO BULLSHITTERS

Here’s one way to measure our progress: take some people who are armed with the psychological literature and pit them against other people who are armed only with their own intuitions. The more we learn, the more this should be like a fight between gun-toters on one side and knife-wielders on the other. For instance, a bridge built using actual physics should hold up better than a bridge built using folk physics.

We don’t run a lot of these John Henry-style showdowns, but when we do, psychology does not win a resounding victory. Here are three examples.

1. Our anti-hate interventions are about as good as a Heineken commercial

The Strengthening Democracy Challenge tested all sorts of ideas for reducing animosity between Democrats and Republicans. Many of them didn’t work. One of the top performers, though, was this Heineken ad from 2017, which was made not by psychologists for the purposes of helping people get along, but by marketers for the purposes of selling beer.

2. Licensed therapists aren’t obviously better than a random nice person

In clinical and counseling psychology, there’s an ongoing debate about whether their training actually does anything. One uncomfortable finding: trainees can do just as well as fully licensed therapists.

In fact, in the late 1970s, two researchers assigned2 a small group of college men to receive treatment either from trained therapists or from professors in a variety of disciplines who were selected based on their “untutored ability to form understanding, warm, and empathetic relationships.” At the end of the study, it looked like the professional therapists and the affable professors were equally effective. This study is too small and low-quality to count for much, but it’s concerning that it wasn’t a slam-dunk in favor of the pros.

3. Personality psychologists perform about as well as shamans

The Big Five theory claims that all aspects of human personality boil down to five factors: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. There’s some disagreement about whether it’s better to describe personality using six or two factors or whatever, but most people will tell you that the Big Five is solid, a great achievement, a good theory backed up by decades of empirical studies.

So how well does the Big Five perform against, say, some personality tests that people pulled out of their asses?

A group called ClearerThinking tested exactly that by comparing the Big Five to the Meyers-Briggs Personality Indicator3 and the Enneagram, two personality assessments that were created outside of academic psychology. (The Enneagram was apparently invented by a series of spiritual teachers, and until Isabel Briggs Myers popularized her eponymous personality test, she was most famous for writing racist detective stories.) The ClearerThinking folks checked how well each test predicted things about participants’ lives, like whether they’re married, own a home, have been convicted of a crime, meditate daily, and have a lot of friends.

Here are the results (taller bars = better predictions):

The Big Five comes out ahead, but part of its lead comes from statistics rather than psychology. The Big Five uses continuous scores (i.e., “you’re a 12 on the agreeableness scale”) rather than converting everything to four letters like the Meyers-Briggs does (i.e., “you’re an ENTJ”), or to a single number like the Enneagram does (i.e., “you’re a nine”). Collapsing scores like that makes them easier for humans to interpret—which is exactly why they do it—but it throws away data, so in a statistical showdown you’re shooting yourself in the foot.4

If you use the continuous Meyers-Briggs and Enneagram scores, the Big Five’s lead narrows or disappears altogether (higher numbers = better prediction):

When I saw this result, I broke out in a sweat. Whatever it is we psychologists do, we’ve done a lot of it to the Big Five. After millions of dollars and thousands of studies, we are not obviously better at predicting life outcomes than people who… didn’t do any of that.

3. WE HAVE A HARD TIME USING OUR KNOWLEDGE TO DO STUFF

The magic of basic science is supposed to go like this: if you let the nerds chase their little science fantasies, they will eventually—but unpredictably—produce something useful, even if they never intend to. That’s a good sign the nerds are onto something, and not just spending the grant money on beer and Warhammer figurines. In psychology, progress of this kind might look something like, “we’re getting better at treating mental illnesses.”

We do not appear to have progress of this kind. According to this meta-analysis, we’re no better at treating youth mental illness today than we were 50 years ago. This one says we haven’t gotten any better at treating adult depression. In fact, there was some worry that cognitive-behavioral therapy was becoming less potent over time; that might be a statistical artifact, but the best-case scenario is that it hasn’t gotten any better.

Another way of thinking about it: of the 298 mental disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, zero have been cured. That’s because we don’t really know what mental illness is, which you can tell by the fact that every diagnosis has an “unspecified” version, where the therapist goes “I dunno, you’re kinda messed up in this general direction.”

On the experimental side, our biggest success story is supposed to be “nudges,” or small environmental changes that help people make better decisions. At least 12 countries have started some kind of “Nudge Unit” to harness “behavioral insights” for the good of their citizens, and one of the nudge fathers won a Nobel Prize, so this seems pretty solid.

When you watch the nudgers in action, though, it doesn’t look like we’ve learned that much. In 2022, a big group of psychologists published a “megastudy” where they tried 53 different interventions to increase gym attendance. These are the best behavioral scientists in the biz, working with a big budget, and trying to get people to do something they already do and want to do even more.

The results: less than half of the interventions worked. When experts in behavioral science and public health tried to predict the outcomes, they did no better than chance.

(In another megastudy—this one on vaccine messaging—non-experts were actually better than experts at predicting which interventions would work.)

So yes, we can change people’s environments to help them make better decisions, but we still don’t really know how to do this. Even our best ideas sometimes backfire. For instance, the original book on nudging pointed out that people are more likely to become organ donors when you make them opt out, rather than opt in. And yet, countries that have since switched to an opt-out system have seen the number of organ donors sometimes increase, sometimes decrease, and sometimes do nothing at all.5 Our state-of-the-art is still “think of 53 different things and then try all of them.” This isn’t super reassuring—if I hired a plumber to install a toilet in my house and he was like, “Sure thing, I’ll just install 53 different toilets and then check which ones flush,” I’d be like, “perhaps I’ll get another plumber.”6

4. WE HAVEN’T BEEN ABLE TO TURN OUR KNOWLEDGE INTO TECHNOLOGY

The nice thing about a modern internal combustion engine is that you don’t have to know anything about combustion to use one. It wasn’t always that way: the first engines were so finicky and complicated that only engineers could run them. When we understand something well enough that we can cram it into a box and hand it over to a non-expert, that’s progress.

I don’t think psychology has anything like this. The closest thing I can think of are apps and programs that are built around ideas from psychology, like Anki (a memorization app), Save More Tomorrow (a retirement savings program), or any of the CBT apps on the market today. But beyond those literal three things, I’m drawing a blank. I know lots of things will claim to be built on solid psychological findings, but that doesn’t mean they actually are, or that they actually work, or that those findings are actually solid.

5. OUR OLD QUESTIONS HAVEN’T BECOME SILLY YET

If I go to the doctor and I’m like, “Doc, I’m coughing and sneezing all the time, which one of my humors is outta whack?” all I’m going to get is a blank stare. You could say my question is wrong, but it’s more accurate to say it’s nonsensical. This just isn’t the way we think about things anymore—we have a totally different worldview that doesn’t include humors at all. That’s a sign we’ve undergone a paradigm shift, and it’s potentially a sign of progress.

Psychology hasn’t done this. For instance, it’s true that lots of psychologists will look at you weird if you ask a question like, “Does this phenomenon have more to do with the id or the superego?” But many other psychologists would be happy to answer a question like that. 29% of practicing therapists—a plurality—are trained in the psychodynamic tradition, where such ideas are still mainstream. You can get trained in “contemporary Freudian” psychoanalysis at Columbia, Emory, and NYU. A psychologist who dispenses cognitive-behavioral therapy and a psychologist who interprets your dreams could have the same degree from the same university. They could even be the same person.

WON’T YOU BE MY BASIL VALENTINE

I’ve made versions of this argument to lots of people, and the most common response I get goes something like this: well, this is as good as it gets! Unlike the physical world, where you can explain lots of things with a few simple laws, humans are very complicated—random, even. There are too many variables! That’s why psychology will never be a “real” science.

The more history I learn, the funnier this argument seems.

I recently read The Secrets of Alchemy by Lawrence Principe, which I loved, especially because he tries to replicate ancient alchemical recipes in his own lab. And sometimes he succeeds! For instance, he attempts to make the “sulfur of antimony” by following the instructions in The Triumphal Chariot of Antimony (Der Triumph-Wagen Antimonii), written by an alchemist named Basil Valentine7 sometime around the year 1600. At first, all Principe gets is a “dirty gray lump”. Then he realizes the recipe calls for “Hungarian antimony,” so instead of using pure lab-grade antimony, he literally orders some raw Eastern European ore, and suddenly the reaction works! It turns out the Hungarian dirt is special because it contains a bit of silicon dioxide, something Basil Valentine couldn’t have known.

No wonder alchemists thought they were dealing with mysterious forces beyond the realm of human understanding. To them, that’s exactly what they were doing! If you don’t realize that your ore is lacking silicon dioxide—because you don’t even have the concept of silicon dioxide—then a reaction that worked one time might not work a second time, you’ll have no idea why that happened, and you’ll go nuts looking for explanations. Maybe Venus was in the wrong position? Maybe I didn’t approach my work with a pure enough heart? Or maybe my antimony was poisoned by a demon!

An alchemist working in the year 1600 would have been justified in thinking that the physical world was too hopelessly complex to ever be understood—random, even. One day you get the sulfur of antimony, the next day you get a dirty gray lump, nobody knows why, and nobody will ever know why. And yet everything they did turned out to be governed by laws—laws that were discovered by humans, laws that are now taught in high school chemistry. Things seem random until you understand ‘em.8

So yes, it’s possible that psychology is nothing like any science we’ve ever done before, that we’ve finally met our match, that progress will always be modest, and we should be happy with what we got. But that prophecy is self-fulfilling: if you think this is all we can do, then this is all we will do.9

When I look at the progress psychology has and hasn’t made, I don’t come to the conclusion that we’re dumb; I come to the conclusion that we’re young. We’re early in our history. This is, I think, the fundamental disagreement I have with so many of my colleagues, who seem to think we’re in our middle age, if not beyond it. That would explain why they’re so interested in fact-checking our legacy and making sure that everything we do fits nicely into everything we’ve done before—these are things you do when your field is advanced in years.

But if you think we haven’t even hit puberty yet, you entertain far stranger thoughts, like “How might we finally grow up?”

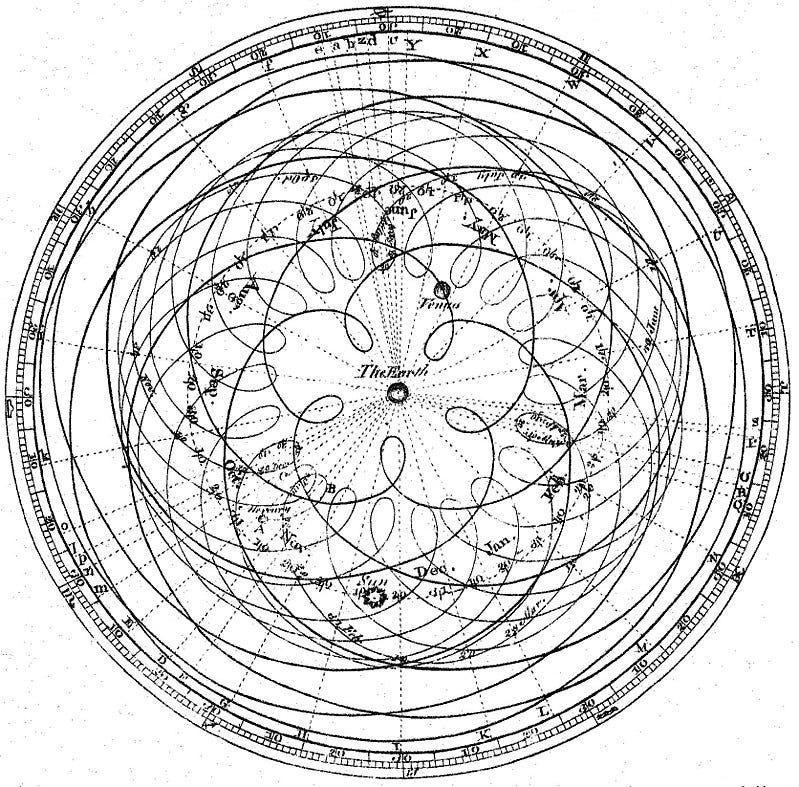

LUPÉ FIASCO? MORE LIKE LOOPY FIASCO

Scientific revolutions arise from crises—that moment when we’ve piled up too much stuff that doesn’t make sense and the dam finally breaks, washing away our old theories and giving us space to build new ones The classic example is epicycles, the little loop-de-loops that old-timey astronomers had to add to the orbits of heavenly bodies so that the math on geocentrism kept working out:

Eventually there were too many loops, and the whole system collapsed.

Nothing like this will ever happen in psychology. Our theories are never fact-checked by the movements of the sun and the planets, and our beliefs are too vague and expansive to be troubled by the appearance of a new finding. Our appetite for epicycles is therefore infinite—or, really, we have no orbits to attach them to, so it’s epicycles all the way down. We’re like a pressure cooker with the valve jammed open; all the steam escapes out the top, so no pressure ever builds up.

If we want a crisis and a revolution, then, we’ll have to engineer one ourselves.

THE MYSTERY OF THE TELEVISED SALAD

I see two ways forward, which I’ll only sketch out for now, because we’re already at the butt-end of a long post.

One: we can keep debunking folk psychology. Our intuitions about other people run deep and strange—the book of folk psychology is likely several times longer than the books of folk physics, folk biology, etc., so there are plenty of pages left to edit. I think that’s a cool thing to do, and I’ll probably keep doing some of it myself. So far, however, our considerable progress on this front doesn’t seem to have caused lots of progress on the other fronts, and I’m not optimistic that will change in the future. That’s why I don’t think we should only do this.

Two: we can shake things up. And I mean really shake things up. The philosopher Michael Strevens says that doing science requires an “alien mindset” where you entertain ridiculous thoughts like “perhaps Aristotle needs some updating” or “maybe we should toss balls of varying weights off a tower and see which one hits the ground first.” Those thoughts don’t seem alien anymore, of course, because they worked out. But going full alien-brain today means you will have to entertain thoughts that incur reputational risk, like “maybe you don’t have to pay attention to the literature” and “maybe we should ask people how their toothbrush could be different“.

Once you get into the alien mindset, the best thing to think about is mysteries. What are the self-evident phenomena: things that definitely happen, but that we cannot explain? Here are a few:

The average American watches 2.7 hours of television per day. We write this off as “leisure,” as if that’s an explanation. Why is it fun to watch someone make a salad on TV? Why do some people find it fun to stare at a person spinning a wheel and buying vowels, while other people find it fun to stare at vampires kissing? Why can an episode of “Paw Patrol” stop rampaging toddlers in their tracks?

People come up with new things all the time—new business ideas, new novels, new salads to make on TV. How do they do this? We’ve got mathematicians saying that the solution to a problem just appeared to them while they were getting on a bus, we’ve got writers saying they feel like they’re “taking dictation from God”, we’ve got Paul McCartney saying “Yesterday” came to him a dream. What the hell is going on here?10

Why do so many drugs have paradoxical reactions? For example: some people feel better when they take antidepressants, but some people feel way worse. Some of this mystery will have to be unraveled from the bottom up by the folks who study the brain, but some of it will have to be unraveled from the top down by the folks who study the mind.

I gotta say, making that list was hard! Thinking of mysteries is kind of like trying to imagine a color you haven’t seen before. I’d love to see more lists of self-evident phenomena we can’t explain; not “how do we reduce scores on the Modern Racism Scale by 10%” but “people do this weird thing…WHY.”

These, I think, are the only two paths that lead anywhere. If we try to falsify folk psychology, or if we start back at square one, we stand a chance at making progress. Otherwise, we’ll just keep making our stack of papers taller and taller, to no avail.

Okay, enough! Godspeed to us all, and may we all meet one day in Cincinnati, where our reward shall be great:

Whenever I mention Milgram I have to say that, despite attempts to debunk his work, I think it remains bunked. So many old studies have turned out to be fraudulent or at least misrepresented—the Stanford Prison Experiment, Robbers Cave, the Rosenhan pseudopatient study—that I think people are now too quick to assume that everything famous and old must be fantastical.

I would say randomly assigned, but the authors are evasive about just how random the assignment was: “Assignment was intended to be random, but certain compromises were dictated by clinical realities, such as availability of therapists.” Another reason why I find this study provocative, but not necessarily trustworthy.

Technically they had to use a test “inspired by” the Meyers-Briggs because the actual test is proprietary and paywalled.

I learned of this study from this recent post on nudging by the economist Maia Mindel.

Plus, as the economist/evolutionary biologist Jason Collins points out, you shouldn’t even expect interventions that “work” to generalize very far—if something worked at a gym, would it also work at a yoga studio? Would it work on elderly people? Would it work for getting people to return their library books? The only way we could answer those questions is by running megastudy after megastudy.

Probably a pseudonym, and a dope one. No word on whether Basil Valentine ever tried to turn himself into scorpions.

In fact, when psychologists discover that someone has failed to replicate their finding, they sound a lot like exasperated alchemists from the 1600s: “No, you idiots! The experiment didn’t work for you because you don’t have the right touch!”

For more on the parallels between modern-day psychology and old-timey alchemy, see Ethan Ludwin-Peery’s Alchemy is ok.

I realize there are hundreds—if not thousands—of papers on “creativity,” but just because much has been done, that doesn't mean much is known. (If you handed Paul McCartney the entire literature on creativity, would he write more “Yesterday”s?) The best thing to do is forget all of it, estrange yourself from the word “creativity” entirely, and start with the extremely bizarre fact that humans write songs and novels and solve math problems, and we don't know how this happens.

Love your work, Adam, but have to take issue with 2 things here - one big & one small (I’m not an academic psychologist; I’m an academic in another field, so I’m not defending my turf).

1. Solving psychiatric illness: Real, important, replicable progress is being made every year. Tens, maybe hundreds, of thousands of people just in the US can live independent and meaningful lives because they take psychiatric medication for serious psychiatric illnesses. This includes major and treatment-resistant depression, treated with TMS or neurostimulators. I recognize that you are writing about psychology and not psychiatry, but: (a) you said that nothing in the DMS has been “cured”; yet people with serious DMS diagnoses *can* be fully treated; and (b) making the argument that psychology is no better now than it was 50 years ago leads to treatment nihilism, which can seriously harm people who then miss out on effective treatments.

2. “Big 5.” It may be that the big five are no more predictive than hocus pocus, but you can’t tell that by looking at whether somebody buys a house in their lifetime. It’s the wrong endpoint. I could predict, on an average basis, who will or won’t buy a house in their lifetime and it doesn’t have anything to do with psychology. I would ask: 1. Are they White? 2. Have they received an inheritance or other chunk of change from a family member? Being white and receiving intergenerational wealth (two variables that are also correlated) are the strongest predictors of home ownership. We should not expect psychology to predict unlike types of social facts.

Thanks again for the great article. Please keep up the great work!

I was interested to see you list Anki as a success at “cramming it into a box,” because I’ve spent about ten years developing, supporting, and writing about spaced-repetition systems in some capacity (including Anki), and I’ve often written about how using memory tools well is actually very complicated, noting that if only we could find a prescriptive set of simple rules you could follow (like you could encode into software) that would consistently work, it could finally take off!

Anki does do a good job at packaging up the insight of spaced repetition itself. Unfortunately, that is only a tiny part of the problem of learning/remembering things, and solving this restricted problem leaves most of the real problem unsolved. Just a few common and important problems it doesn't solve:

* Lack of motivation / habit – people forget to study, don't want to study, don't study for a few days and then come back and have a huge pile of cards and give up, etc. (This is moderately tractable – I think RemNote, the startup I’m currently involved in, does much better than Anki does here – but habits are just hard, and there’s only so much you can do to help people remember things if they don’t review them!)

* Learning something that's useful / you care about knowing – it's super common for people to use Anki to memorize, say, all the symbols on the periodic table, and then if you ask them why they wanted to know that, they have no idea.

* Writing cards that are unclear – oftentimes when you write a card (or write one for someone else to import), you think you know what it’s asking, but when you actually see it out of context 3 months later it is inscrutable, or makes you think you were supposed to give some other answer instead. In the best case, this is frustrating and messes up the spacing algorithm because you can’t accurately evaluate how well you remembered the content once you fix it. More commonly, people who don’t have a lot of experience don’t even notice why they didn’t know the answer, and keep forgetting the card over and over again without ever doing anything to fix it.

* Learning the thing the way you need to remember it – it’s really easy to memorize a card based on, say, some unusual wording on the front of it, and find yourself unable to recall the information when given a real-life cue. Or you might just ask the question in a way that doesn’t match how you’ll be asked to recall it, and find you just can’t quite make the connection when you are. (Memory is much more sensitive to tiny shifts in context than most people realize.)

* Keeping cards relevant / understanding why you’re struggling – it’s common for cards to become stale because you no longer care about the information on them, or you don’t understand what they were supposed to mean, so you struggle to remember them, and you just keep repeating them over and over again until you get frustrated.

Maybe the core issue is that the apparently simple problem of "remembering question/answer pairs" is deeply tangled up with all sorts of other complicated human stuff that prevents you from actually effectively using the tool unless you also solve those other problems (or at least partially address them). I appreciate the claim that the “people are just complex” argument is unimaginative, but I suspect this may be where psychology really does diverge from, say, physics. Sure you're ignoring all kinds of factors when you, say, model the trajectory of a ball you throw. But with just a couple of equations, you still get answers that are accurate enough to do amazing things to a pretty decent degree of accuracy – you can really forget about a lot of the adjacent questions (e.g., relativity, or often even air resistance). Whereas if you just hand someone Anki, it’s still better than them not having it, but the vast majority of people get resoundingly mediocre results, because of all these adjacent issues, and there's not an obvious way to cram solutions to those issues into the box, because they deeply depend on parts of your internal mental state that can't be reliably introspected. This is frustrating, so most people give up, even though the spaced-repetition tool itself is extremely powerful.

Now I guess you could argue something similar about the ICE. Like of course having a great ICE doesn’t mean people will become good drivers, that's a separate problem to solve, and that shouldn’t diminish the beauty of putting combustion in a box. But there’s some way in which dismissing it like this feels unsatisfying to me – with the ICE that seems so obvious as to be absurd, while with spaced repetition it really feels to me like the fundamental problem is basically unsolved, and we’ve only handled some tiny restricted subproblem. Is it just that we think about psychology differently? Or that the path to making cars safer is clearer than the path to understanding what cards will change someone's mental state into being a person they prefer to be? I’m not sure.

(I have a bunch of blog posts about addressing some of these issues with memory tools – by developing personal skills, not by improving the tools – for anyone curious. You can start at https://controlaltbackspace.org/precise/.)