Good ideas don't need bayonets

OR: Keep stomping necks until utopia arrives

Ever since I published The rise and fall of peer review and got a bunch of comments, I’ve talked to a lot of folks about how to fix science. So far, I’ve realized two things:

Almost everybody is hankering for a better way. (Woohoo!)

Some people are hankering for a fascist dystopia instead. (Uh oh!)

Strangely often, I’ll be talking to someone about all the problems with academic science and everything will be normal and then all of a sudden they’ll reveal a bunch of tyrannical fantasies. Force reviewers to sign their reviews and hold them accountable if the paper’s results don’t hold up! Centralize all journals onto a single website and make everybody submit their papers there! Mount an academia-wide inquisition to identify the data-fakers, the p-hackers, and the over-claimers, and march them off to Science Jail!1

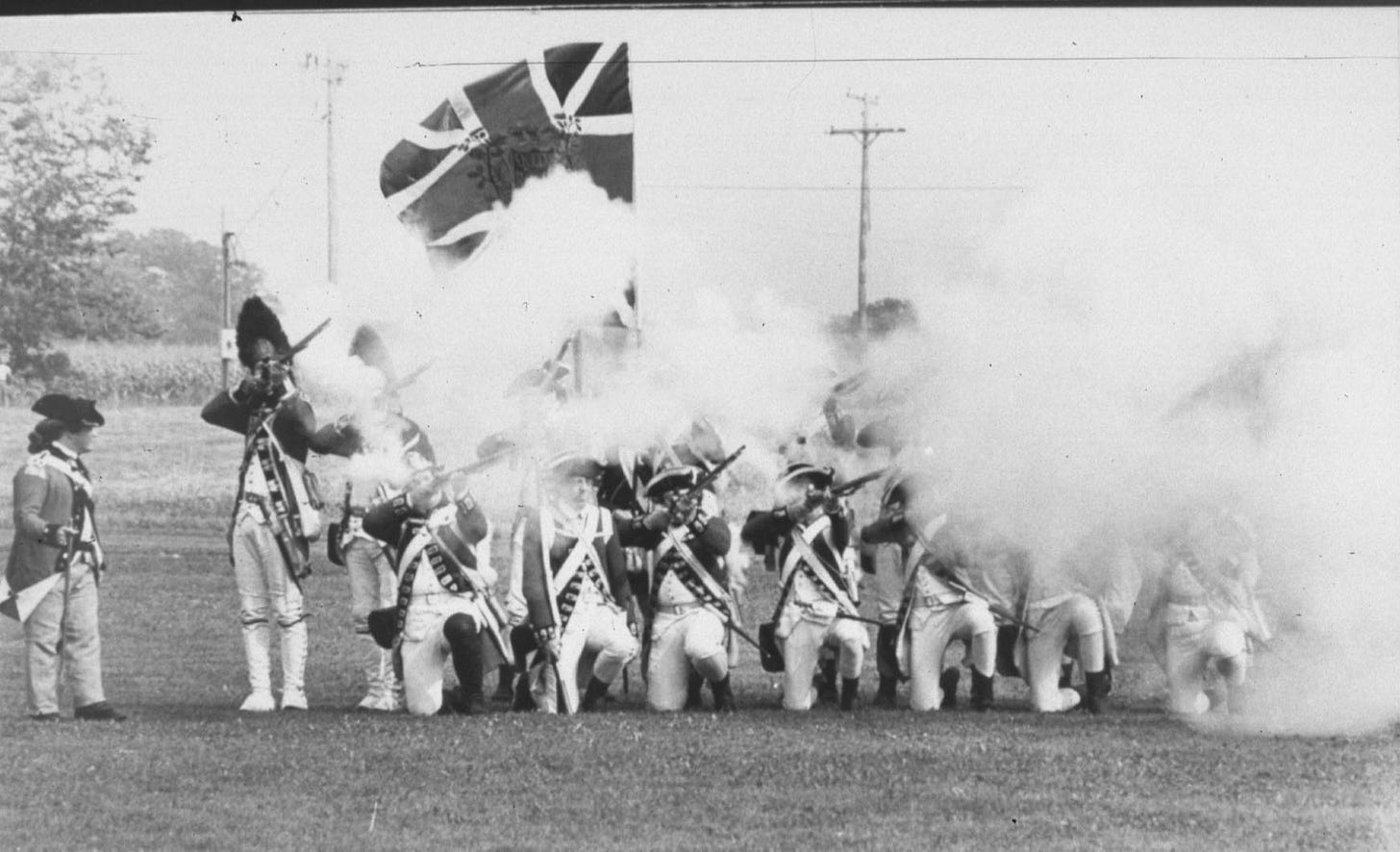

I’m always a little shaken by these conversations. I agree with some of the goals—I would like less fraud and more replication, too. What creeps me out is that people seem to imagine all of these improvements happening at gunpoint. Turns out a lot of academics are itching to ditch their tweed jackets for jackboots and battle rattle.

They’re not alone. I love people, but a lot of them—maybe most?—yearn for their side to acquire absolute power. They seem to believe in the authoritarian school of social change: the only way to create a better world is for a strong central actor to force it on everybody else. They don’t think of this as tyranny, of course. They think of it as doing the right thing. And if a thing is right, well, duh, you should make people do it!

The most hideous ideologies are often the ones we believe without even realizing it. They feel like breathing air and eating food, so natural and necessary that the alternative never occurs to us. I think the authoritarian school of social change is one of those. (Hence why its acronym is ASS-C.)

If the idea of well-intentioned fascism doesn’t already give you the heebie-jeebies, I’m not sure how to convince you that it should. But perhaps I can convince you that it doesn’t work.

CHANCELLOR OF SCIENCE, HEAR MY PLEA

Sometimes when people are enumerating their autocratic wishlists for science, I wanna ask, “Who are you talking to?”

There is no Chancellor of Science who gets to reform research by fiat, nor any Science Gestapo to carry out her wishes. So when you’re like, “We should make sure that science is good!”, there is no one to receive your request.

Science works the way it does because of millions of people making millions of decisions all distributed throughout a big, convoluted network controlled by nobody in particular. Some of these actors are government agencies that are theoretically accountable to the public, but many of them aren’t: private universities, philanthropic foundations, scientific journals, and, of course, the individuals who actually do the science. There is no apparatus that can make all of these actors behave differently, so proposing some kind of system-wide change is a bit like proposing revisions to the Laws of Motion—your suggestion has been duly noted, but it will not be put into effect.

This is how most of the world’s problems work. There is no manager to speak to, no master switch that can turn the bad thing off, no Committee on Problems who could decide to discontinue this particular snafu. You cannot vote to abolish traffic or petition to end hunger—or, you can, but it won’t do anything other than give you the warm glow of appearing to solve a problem without actually solving it.2

Some people believe that nefarious actors are trying to establish a globe-governing New World Order. That is, of course, a crazy belief. It’s even crazier, however, to believe that the New World Order already exists, and that it has a suggestion box.

THE THREE LIES OF POWER

For an aspiring authoritarian, though, it’s no problem that the means of enforcement aren’t there already. We should simply create them. And this is where I wring my hands into raw little nubs, because this point of view relies on a few wildly hopeful and incorrect assumptions about how power works.

The first assumption is that the good guys will always have more power than the bad guys. History hasn’t exactly borne this out. Constructing a network of reeducation camps might seem like a good idea when you get to pick the curriculum, but elections and revolutions are unpredictable things, and next year you might be the one sent to the countryside to be de-programmed. When I see someone salivating over the idea of a Science Gestapo, I have to marvel at their faith that authorities only ever prosecute guilty people.

The second assumption is that, when the good guys acquire unlimited power, they’ll know what to do with it. Unfortunately, reasonable efforts to improve things often fail. We are still barely beginning to understand human behavior, which is why I’m always skeptical about plans to construct giant Human Behavior Control Machines. Policies and technologies often have unintended consequences, not just in the sense of “oops we did the opposite of what we intended” but also in the sense of “oops we didn’t even think that was a possible outcome.” The people inventing the internet in the 1970s and 80s probably didn’t predict that, forty years later, we’d be debating whether it causes teenage girls to kill themselves.

And the third assumption is that good ideas are powerless and need to be spread by force, like an infant emperor who relies on wise vizier to secure the realm with soldiers and swords. This assumption is probably aided by the widespread idea that people are stupid: “The only way to get these idiots to accept the truth is to bash a hole in their skulls and insert it manually.”

But this assumption gets the order of operations wrong. Power is not awarded to truth; power comes from truth. Believing true things ultimately makes you better at persuading people and manipulating reality, and believing untrue things does the opposite. The best ideas don’t need bayonets.

Here’s an example. For decades, the Soviet Union’s official position was that modern genetics is capitalist-imperialist pseudoscience, and that the secret to increasing crop yields is “something something graft plants together, thus unlocking their worker spirit.” Thousands of dissenting biologists were jailed or purged. Meanwhile, the crops failed and people starved.

It turns out that even global superpowers can’t change reality by fiat. Marxist genetics lost to actual genetics because Marxist genetics was wrong, not because a bunch of Western geneticists stormed the Kremlin and made Khrushchev sign an executive order. Ideas can succeed in the short run by being politically convenient, but they succeed in the long run by being true.3

SYSTEM OF A FROWN

When I do my little spiel about the problems in science, the most common question I get is, “Well, then, how should the system work?”

This is a totally reasonable question to ask, but it’s also the wrong one, because it assumes that there should be a system. If we start there, we’re baking in our status quo bias, and we’ll almost certainly end up with a “system” that shares 98% of its DNA with the one we have right now.

(There is also, I find, an occasional twinge of authoritarianism in this question, as if to ask, “Well, if you don’t like how we’re stomping on people’s necks right now, whose necks should we be stomping on?”4)

The better way to pose this question is to tack a few extra letters onto the front: how should the ecosystem work? As soon as you start thinking in ecosystems, you stop imagining that everyone has to live under one New World Order. You start wondering what mix of organisms might keep the ecosystem healthy, and how they might coexist with one another.5

Most importantly, when you think in ecosystems, you start thinking about where you might fit in. The greatest cost of authoritarian thinking—besides the whole stomping on necks thing—is that it only ever leads us to ask, “What should the all-powerful leader do?” instead of “What should I do?”

That’s what I’m always aching for in every conversation about the future of science, or indeed, the future of anything. What are you going to do? Dream about utopia, complain that we don’t live in one, and then go back to doing the same things you’ve always done?

BUT WHAT IF POL POT HAD A PHD

In college, I knew this guy who was always talking about how the world should be ruled by a “panel of experts.” It went without saying, of course, that he would be on the panel—who better to serve than the person who had come up with the idea of the panel in the first place?

I get the appeal of a Committee of Enlightened Despots. The word “enlightened” is right there! Unfortunately, it’s followed by the word despot. The problem with despots is not that they haven’t read enough books, or even that they believe the wrong things. It’s that they’re despots. Tyranny is a bad form of government even when the tyrants have liberal arts degrees.

We yearn for an enlightened despot because the world is complicated and change is slow and incomplete and frustrating. But that’s exactly why we shouldn’t have one person in charge. What are the chances that all of the correct beliefs happen to coexist inside one person’s brain? Or even within a few people’s brains, however expert they may be? And what are the chances that the correct beliefs also just happen to be the ones you agree with?

When things are complicated and you don’t know what’s going on, your best bet is to make many bets. Which is to say: our best defense against stupidity is not authority, but diversity. I don’t mean corporate-compatible diversity like where a soap commercial has one person who is multiracial and one who has alopecia. I mean a bunch of weirdos trying to figure things out together, and nobody gets to stomp on anyone else’s neck, even when they really want to.

This is exactly what authoritarians cannot abide, and it’s why they’re doomed to fail. Freedom, tolerance, equality, democracy—they make things slow and annoying. But dammit, the crops grow.

People usually say these things behind closed doors, but here’s someone shouting it to the world.

Maybe we learn this authoritarian model of the world when we’re kids and then we never unlearn it. When you’re little, grown-ups can reshape your world at a whim. If you want a later bedtime, or permission to wear your Power Rangers pajamas to school, or dinosaur-shaped nuggets instead of nugget-shaped nuggets, petitioning an adult really is your best bet. Many of us remain in little adult-governed pseudo-realities until we’re 22 or even older, and so we get used to the idea that solving problems is merely a matter of pleasing the right big person—find the right gatekeeper, fill out the right paperwork, send the right email.

This is, of course, the idea behind lizard science and Science House.

Via Wikipedia:

Perhaps the only opponents of Lysenkoism [the “let’s graft plants together” plan] during Stalin’s lifetime to escape liquidation were from the small community of Soviet nuclear physicists: according to Tony Judt, “it is significant that Stalin left his nuclear physicists alone and never presumed to second guess their calculations. Stalin may well have been mad but he was not stupid.”

Can I get a little petty and Freudian for a second? A friend sent me a paper that cited my peer review post as follows:

Some have argued that peer review as it is currently practiced is a “failed experiment” and should be abolished (e.g., Heesen & Bright, 2021; Mastroianni, 2022).

I did say peer review is a failed experiment, but I never said it should be “abolished.” Who would do the abolishing? This is what I mean by an implicit authoritarian ideology—people assume that every suggestion is an appeal for an all-powerful actor to do something.

I think a lot of the jackboot fantasies come from what academics see as collective action problems. To take a well-worn example, most academics dislike the current system of for-profit journals, but individuals have strong incentives to publish in Cell/Science/Nature and so they do, and so publishing in those places remains a strong signal, and so the incentive persists. True collective action are surely one of these cases where "dictatorial" powers are more justified.

That said, there should surely be a strong presumption against taking such measures, and in practice, I agree with you that most (all?) of these ideas don't meet the bar. As much as I hate the for-profit journal system, I don't think it would be a good idea to make it illegal to publish in them or whatever. Better if everyone just agreed that publishing non-open-access papers was cringe.

I know the thinking behind "centralize all publishing to a single website". It's a good example of failing to grasp dynamism and the invisible wages of freedom. *Right now*, arXiv.org is the unofficial central repository of several hard sciences (certainly of mathematics) and offers a de-facto seal of approval that rivals that of many journals. But its nonbinding and informal nature are a crucial part of the reason why it has this authority! Try to make it formal and force every author to go through it, and all the demons that only mildly and occasionally affect it at this moment (censorship, favoritism and somewhat baroque requirements) will descend upon it with claws bared and teeth sharpened. Many of the scientists enthusiastically using it will then declare war on it. I think something similar happened with France's arXiv analogue (HAL).

Something similar happened when automated plagiarism detectors evolved from a useful tool to a formally required part in the process for students and scientists, with few if any opportunities for manual override.