Three Dumb Studies for your consideration

OR: sugar daddy salt bae

It’s cool to run big, complicated science experiments, but it’s also a pain in the butt. So here’s a challenge I set for myself: what’s the lowest-effort study I could run that would still teach me something? Specifically, these studies should:

Take less than 3 hours

Cost less than $20

Show me something I didn’t already know

Be a “hoot”

I call these Dumb Studies, because they’re dumb. Here are three of them.

(You can find all the data and code here.)

EXPERIMENT 1: I AM BABY

I’m bad at tasting things. I once found a store-bought tiramisu at the back of the fridge and was like “Ooh, tiramisu!” Then I ate some and was like, “Huh this tiramisu is kinda tangy,” and when my wife tasted it, she immediately spat it out and said, “That’s rancid.” We looked at the box and discovered the tiramisu expired several weeks ago. I would say this has permanently harmed my reputation within my family.

That experience left me wondering: just how bad are my taste buds? Like, in a blind test, would I even be able to tell different flavors apart? I know that sight influences taste, of course—there are all sorts of studies dunking on wine enthusiasts: they can’t match the description of a wine to the actual wine, they like cheaper wine better when they don’t know the price, and if you put some red food coloring in white wine, people think it’s red wine.1 But what if I’m even worse than that? What if, when I close my eyes, I literally can’t tell what’s in my mouth?

~~~MATERIALS~~~

My friend Ethan bought four kinds of baby food. They were all purees, so I couldn’t use texture as a clue, and I didn’t look at any of the containers beforehand.

~~~PROCEDURE~~~

I put on a blindfold and tasted a spoonful of each kind of baby food and tried to guess what it was.

~~~RESULTS~~~

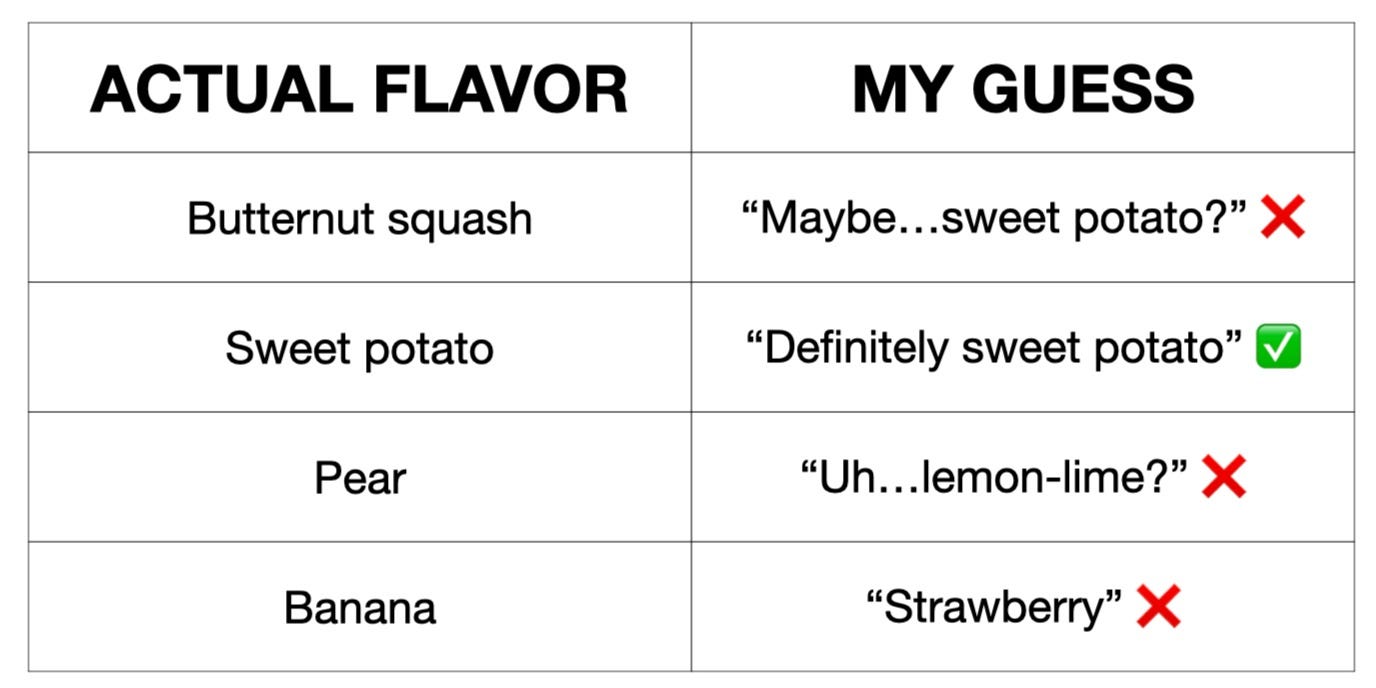

Here’s how I did:

~~~DISCUSSION~~~

I would rate my performance as “humiliating”. Butternut squash and sweet potato are pretty similar, so I’ll give myself that one, but what kind of idiot tastes “pear” and thinks “lemon-lime”? I knew in the moment that there was probably no such thing as “lemon-lime” baby food (did Gerber’s acquire Sprite??), but that’s literally what it tasted like, so that’s what I said. Mixing up banana and strawberry was way below even my very low expectations for myself. When I took the blindfold off, people looked genuinely concerned.2

Here’s something interesting that happened: once my friends revealed the identity of each flavor, I immediately “tasted” it. It was like looking at one of those visual illusions that looks like a bunch of blobs and then someone tells you “it’s a parrot!” and suddenly the parrot jumps out at you and you can’t not see the parrot anymore. Except in this case, the parrot was banana-flavored.

EXPERIMENT 2: MISS PAIN PIGGY LOVES TO PUT HER HAND IN A BUCKET OF ICE

My friends and I were hosting a party and we thought it would be funny to ask people to stick their hands in various buckets, just to see how long they would do it. We didn’t exactly have a theory behind this. We just thought something weird might happen.3

~~~MATERIALS~~~

We got two buckets, filled one with ice water, and filled the other bucket with nothing.

~~~PROCEDURE~~~

We flipped a coin to determine which bucket each partygoer (N = 23) would encounter first. (The buckets were in separate rooms, so they didn’t know which one was coming next.) Upon entering each room, we told the participant, “Please put your hand in the bucket for as long as you want.” Then we timed how long they kept their hands in each bucket.

~~~RESULTS~~~

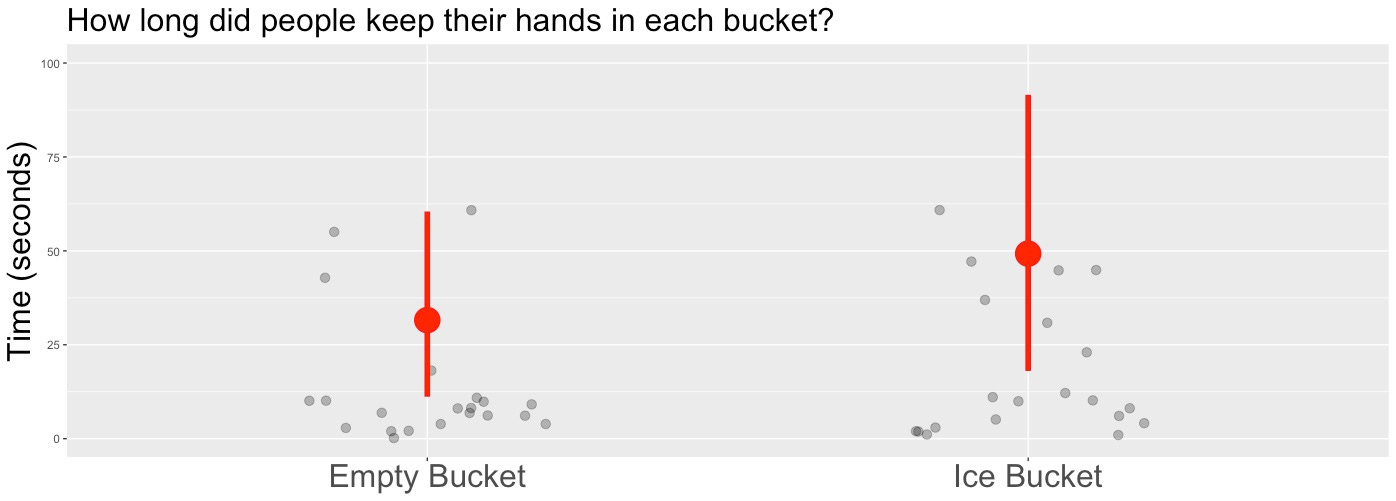

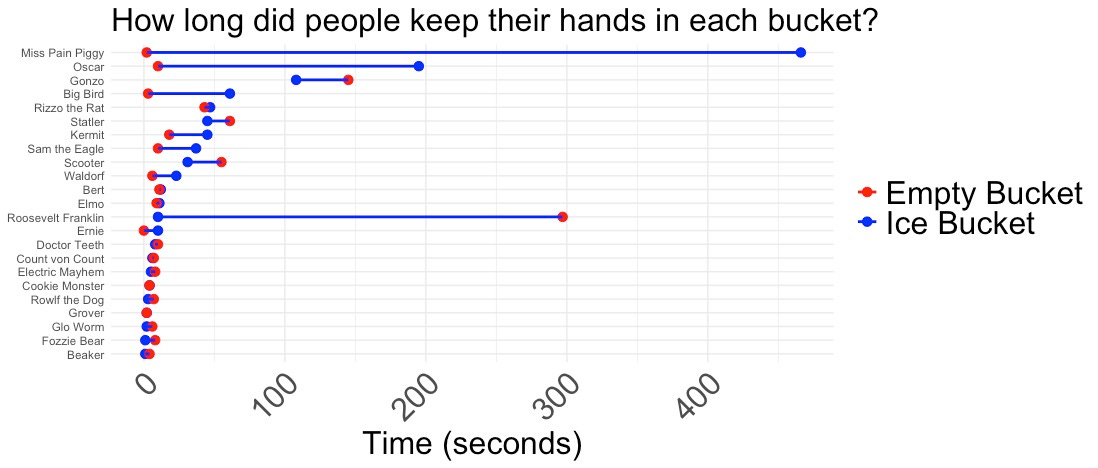

On average, people kept their hands in the ice bucket for 49.26 seconds, and they kept their hands in the empty bucket for 31.57 seconds. The difference between these two averages was not statistically significant.4

But averages aren’t very revealing here, because people differed a lot. Here’s another way of looking at the same data. Each participant has their own row and two dots: a red dot for how long they spent in the empty bucket, and blue dot for how long they spent in the ice bucket. For privacy, all participants’ names have been replaced with the names of Muppets.

~~~DISCUSSION~~~

We learned two things from this study.

People are weird

Putting your hand in a bucket of ice is supposed to be a universally negative experience. It’s known in the science biz as the “cold pressor task,” and they use it to study pain because it hurts so bad. But some people liked it! One guy thanked the experimenter for the opportunity to make his hand really cold, which he enjoyed very much. Another revealed this: you know those drink chillers at the grocery store where you can put a bottle of white wine or a six pack in a vat of icy water and it swirls around and it chills your drink really fast? He used to stick his hand in one of those for fun.

Feeling pointless might hurt worse than feeling pain.

Say what you will about sticking your hand in an ice bucket: it’s something to do. You feel like you’re testing your mettle, your skin changes colors, your fingers tingle and that’s kinda fun. When you put your hand in an empty bucket, nothing happens. You just stand there like an idiot with your hand in a bucket. People think physical pain is inherently negative, like it’s pure badness. But when you lock eyes with Miss Pain Piggy and she holds her hand in ice water for 466 seconds straight, you start to question a lot of assumptions.5

EXPERIMENT 3: SUGAR DADDY SALT BAE

Here’s something that’s always bugged me: people love sugar and salt, right? I mean, duh, of course they do. So why doesn’t anyone pour themselves a big bowl of salt and sugar and chow down? Is it just social norms and willpower preventing us from indulging our true desires? Or is it because pure sugar and salt don’t actually taste that good? Could it be that our relationship with these delicious rocks is, in fact, far more nuanced than simply wanting as much of them as possible?

This study was partly inspired by cybernetic psychology, which posits that the mind is full of control systems that try to keep various life-necessities at the right level. Sugar and salt are both necessary for life, and people certainly do seem to desire both of them. And yet, if you eat too much of them, you die. That sounds like a job for a control system—maybe there’s some kind of body-brain feedback loop trying to keep salt and sugar at the appropriate level, not too high and not too low. One way to investigate a control system is just to put stuff in front of someone and see what they do. That sounded pretty dumb, so that’s what I did.

~~~MATERIALS~~~

I got a measuring spoon marked “1/4 teaspoon” and some salt and sugar.

~~~PROCEDURE~~~

I ran this study at an Experimental History meetup in Cambridge, MA6. I brought people (N = 23)7 to a testing room and sat them at a desk. I first showed them the measuring spoon and asked them, “If I were to give you this amount of sugar, is that something you would like to eat?” If they said “Yes”, I poured 1/4 teaspoon of sugar into a tiny cup and gave it to them. Once they ate it, I asked them to rate the experience from 1 (not good at all) to 5 (very good), and I asked them if they’d like to do it again. If they said yes again, I gave them another 1/4 teaspoon of sugar and got their rating. I repeated this process until they refused the sugar. (Nobody took more than two shots.) Then I repeated the process with 1/4 teaspoon of salt.8 I should have randomized the order, but in all the excitement, I forgot.

~~~RESULTS~~~

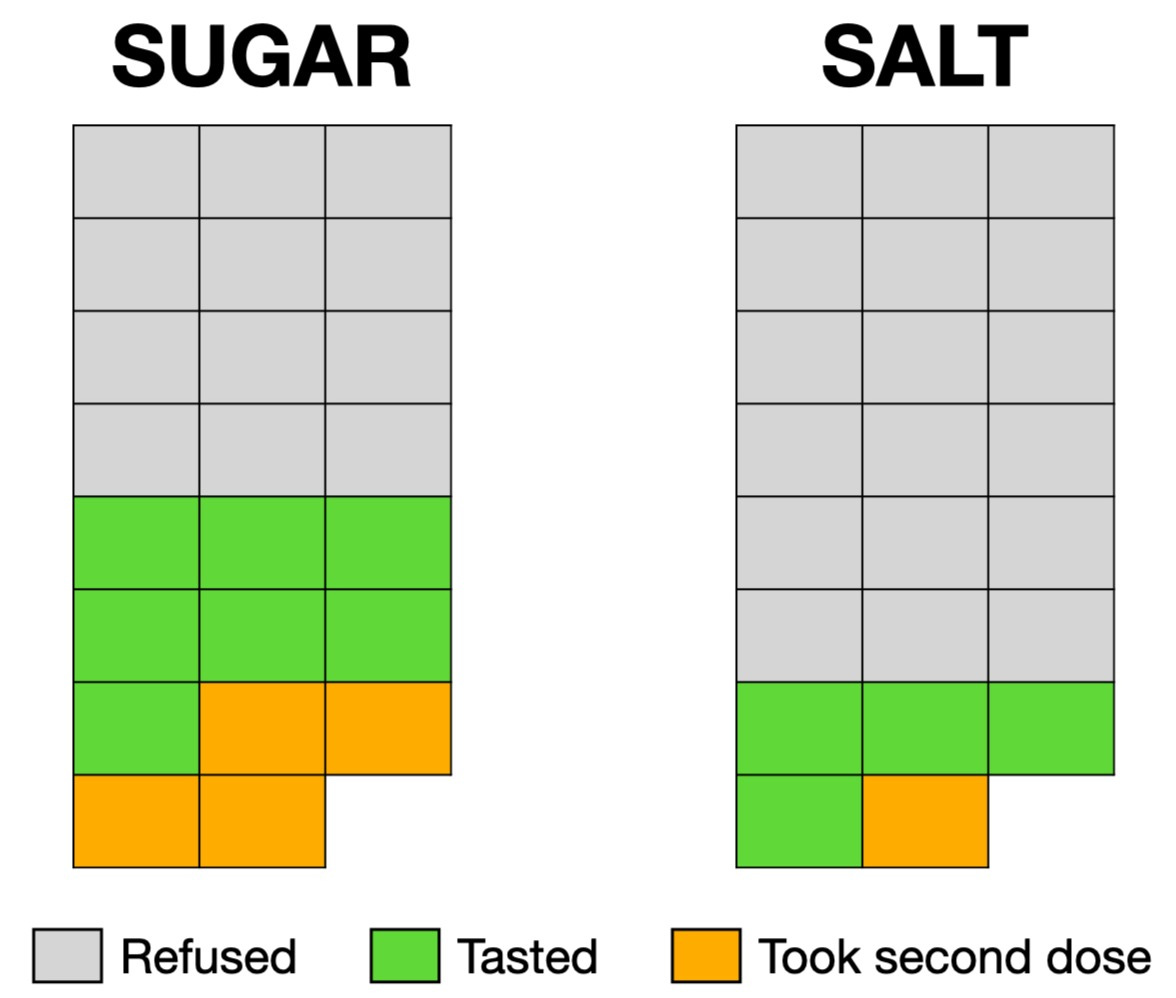

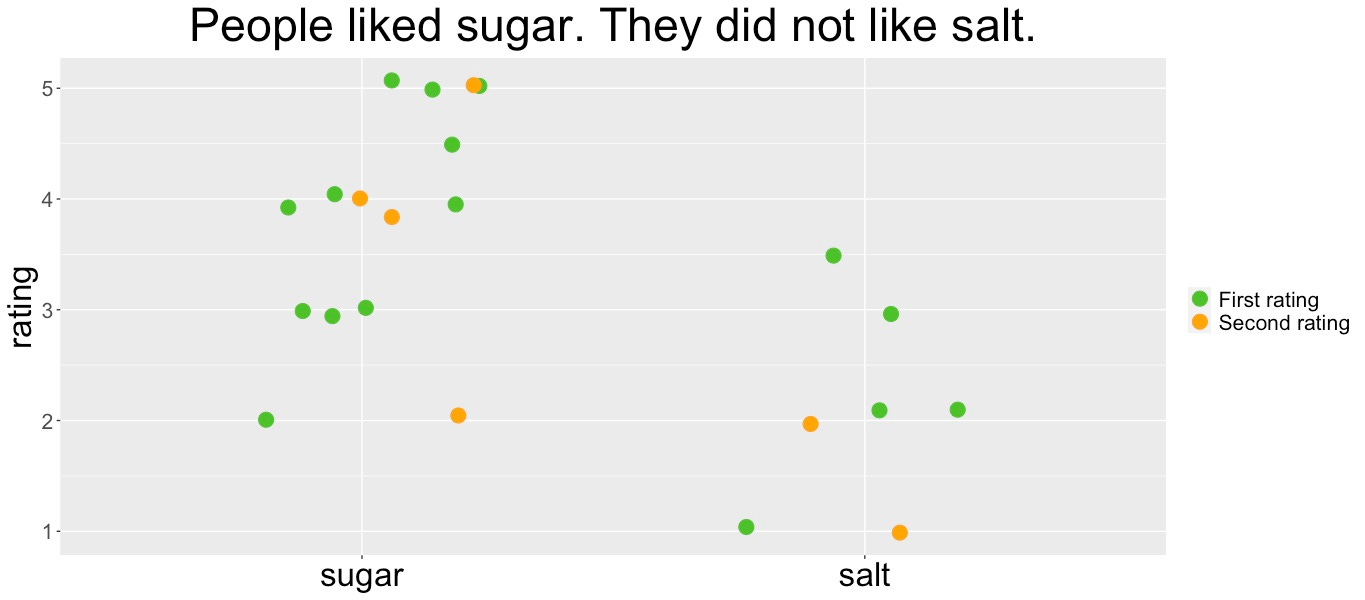

About half of the participants flat-out refused the sugar, and two-thirds refused the salt. Anecdotally, many of the people who refused the sugar said something like, “oh, I’d like to eat it, but I shouldn’t.” People did not feel that way about the salt. They were just like, “No thanks”.9

The people who did try the sugar generally liked it. The people who tried the salt did not. (The latter were, by the way, all men.) A few of the guys put on a brave face after downing their salt, but the rest said things like “blech!” and “oh!”. Four people took an extra shot of sugar, and they liked it fine. The two people who took an extra salt shot gave the experience a big thumbs-down.

~~~DISCUSSION~~~

Why don’t people eat big spoonfuls of sugar and salt? For sugar, the answer might be “we think it’s sinful”. But it also might be because raw sugar isn’t actually super delicious. I’m a bit surprised that the sugar ratings weren’t even higher—isn’t sugar supposed to be pure bliss?10 For salt, the answer might just be “it tastes bad on its own”.

It’s weird that people had such strong reactions to such small amounts. There’s about 1g of sugar in 1/4 teaspoon, and a single Reese’s peanut butter cup—a notoriously delicious treat—contains 11x that much. Meanwhile, 1/4 teaspoon of salt is about 1.4g, and I happily ate more than that in a single sitting yesterday via a pile of tater tots dunked in ketchup. For some reason, people seem to find these minerals far more appealing when they’re mixed with other stuff.

Why would that be? Maybe it has to do with how much you need to survive, and how much you can eat before you die.

The estimated lethal dose of salt is 4g per kilogram of body weight, and people really do die from ingesting too much of it. In one case, a Japanese woman had a fight with her husband, drank a liter of shoyu sauce containing an estimated 160g of sodium, and died the next day. In another case, a psychiatric hospital forced a 69-year-old man to drink water containing 216g of salt (they wanted him to throw up because he had ingested his roommate’s medication); he was declared brain dead 36 hours later.

Meanwhile, the estimated lethal dose of sugar is much higher: 30g per kilogram of body weight. An extremely trustworthy-seeming Buzzfeed article called “It’s Actually Pretty Hard to Eat So Much Sugar that You Die” estimates that the average adult would need to eat 680 Hershey’s Kisses, 408 Twix Minis, or 1,360 pieces of candy corn before they kicked the bucket.

It takes a lot longer to eat several pounds of candy than it does to chug a liter of shoyu, so it’s easier for the body to defend against a sugar overdose than a salt overdose (by making you feel nauseous, cramping, throwing up, etc.). The best way to avoid death by salt, then, is to avoid eating large doses of salt in the first place, and the best way to do that is to make it taste bad. Maybe that’s why the same amount of salt tastes nasty when served raw and tastes delicious when sprinkled over a basket of french fries or dissolved in a bowl of soup—you’re only getting a little bit at a time, so you won’t shoot past your target level.11

Anyway, these results suggest that we do not “love” sugar and salt. We love a certain amount of sugar and salt, consumed at a certain rate, and perhaps even in a certain ratio to other nutrients. The results also suggest that coming to an Experimental History meetup is a super fun and cool time.

THE BURDEN OF RESPECTABILITY

I’m showing you Dumb Studies as if they’re something new. But they’re not. At the beginning of science, all studies were Dumb.

Robert Boyle, the father of chemistry, did a thorough investigation of a piece of veal that was weirdly shiny (results inconclusive). Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, the father of microbiology, blew smoke at worms to see if it would kill them (it didn’t). Robert Hooke, the father of a bunch of stuff12, sprinkled some flour on a glass plate and then ran a bow along the side like he was playing the fiddle and was like “ooh look at the lines the vibration makes”. These studies looked stupid even then, and people duly ridiculed them for it.

Ever since then, the most groundbreaking scientists have always spent a big chunk of their time—perhaps most of their time—goofing around. Francis Galton, the guy who invented like 10% of modern science13, took a secret whistle to the zoo and whistled at all the animals (the lions hated it). Barbara McClintock learned how to control her perception of pain so she wouldn’t need anesthesia during dental procedures. Richard Feynman did about a million Dumb Studies, including a demonstration that urination isn’t driven by gravity because you can pee standing on your head. The neurologist V.S. Ramachandran was able to temporarily turn off amputees’ phantom limbs by squirting water in their ears and making them look at mirrors. They all had what I call experimenter’s urge: the desire to, quite literally, fuck around and find out.

After science became a profession, we started expecting our science to look very science-y, no Dumb Studies allowed. On top of that, the replication crisis left us all with a cop mentality that treats anything fun as suspicious. People want to blame the slowdown of scientific progress on the “burden of knowledge”14 or “ideas getting harder to find”—I disagree, and will fight such people, but I do agree that we're suffering under a modern burden: the burden of respectability.15

There’s a time and a place for the Serious Study. Sometimes you’re spending millions of dollars, for instance, and you can’t afford to be loosey-goosey with the procedure. But reality is very weird, and if you ever want to understand it, you have to bump into it over and over, in as many places and from as many angles as possible. You need the freedom to be Dumb. You must inspect the shining meat, you must pee standing on your head, and you must, I submit, eat this baby food.

I thought this was common knowledge, but apparently it’s not. In this New Yorker article about blind wine taste-testing, a professor of “viticulture and enology” confidently states that no one would ever mix up red wine and white wine right before the author does exactly that.

Come to think of it, why is “strawberry-banana” such a common flavor? Where did that come from?

An initial writeup of this experiment was previously published in the first, and so far only, issue of The Loop.

Specifically, t(22) = 0.69, p = .50. The more statistically-minded folks might be wondering: “Did you have enough power to detect an effect here? You only had 23 participants, after all.” Great question! With N = 23, we have about an 80% chance to detect an effect of d = .6 with a two-tailed paired t-test. That’s roughly what we consider a “medium” effect, based on something one statistician said once. To put that in context, the standardized effect of SSRIs on depression is .4, the effect of ibuprofen on arthritis pain is .42, and the effect of “women being more empathetic than men” is .9. The Bayes factor for this difference is .27, meaning moderately strong evidence for the null, according to something another statistician said once. So we can’t say there’s no difference between the empty bucket and the ice bucket, but if there is any difference, we can be pretty confident that it isn’t large.

Maybe this is also why, if you leave people alone in an empty room with a shock machine, they will voluntarily shock themselves.

This meetup was co-hosted with The Browser, a terrific newsletter that curates interesting internet stuff.

Not a typo; somehow every party I host ends up with 23 people at it. (Some people were there both times, but most weren’t.)

The party took place in the afternoon and had both salty and sweet snacks available, so each person was coming in with a different amount of sugar and salt already in their system.

This was one of the fun parts of running Dumb Studies: you let people do interesting things. In a Serious Study in psychology, for instance, we don’t usually let people say “no”. I mean, we do, obviously, for ethical reasons, but if they refuse some part of the study, then the study is over.

When you run a Dumb Study, you can treat all behavior as data. If someone doesn’t want to put their hand in the empty bucket or they don’t want to eat the salt, that’s not noise. That’s a result.

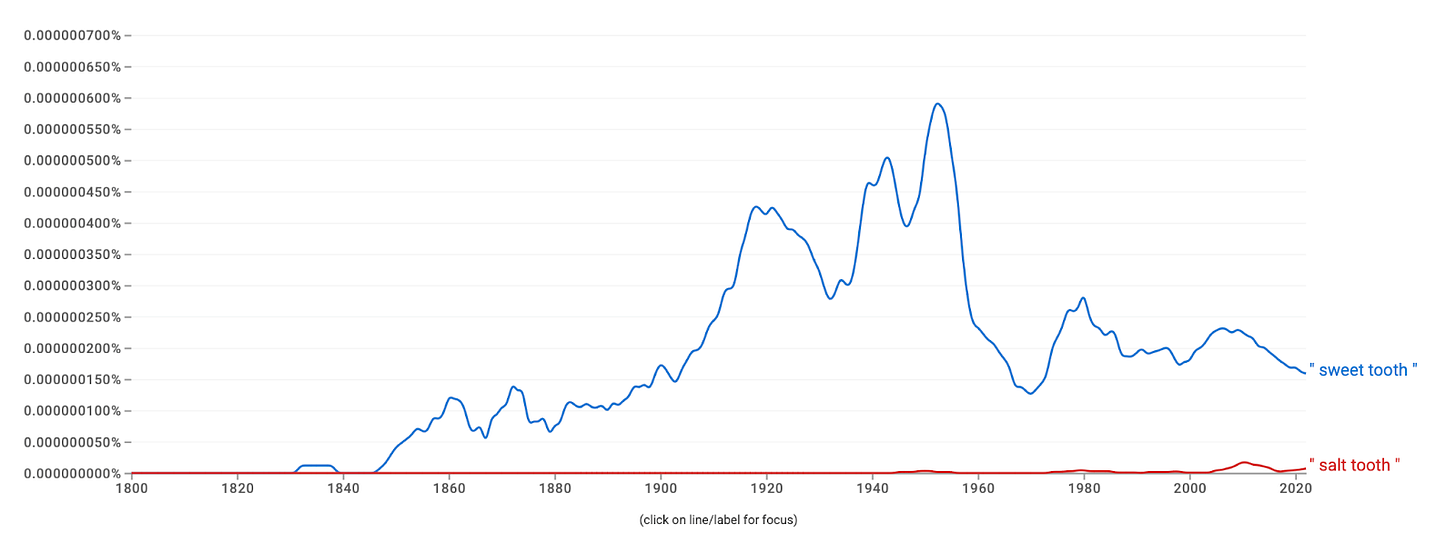

I don’t quite have enough data to tell, maybe there’s more variance in sugar preferences than there is in salt preferences. One participant remarked that he had eaten pure sugar earlier that day. And “salt tooth”, while apparently a thing, is far less common than “sweet tooth”, and it sounds like a D-list pirate name.

This would also predict that Gatorade tastes better after a run on a hot day; you’ve sweated out some of your sugar and salt stores, so your taste buds give you a thumbs-up for re-up.

For instance, Hooke’s law, Hooke’s joint, Hooke’s instrument, and Hooke’s wheel.

To be clear, both good stuff and bad stuff

Supposedly the “last man who knew everything” was English polymath Thomas Young, who died in 1829.

Weirdly enough, “being respectable” does not include “posting your data and code”, which most studies do not do.

This is so awesome! We need to bring back dumb studies especially with kids! In my own little life I was previously paid to be a "Scientist" and also I have people in my family who are antivaxers who decided I was not to be trusted because I was a scientist. (Or maybe it was because I studied plants and microbes?)

I wish, in our current political landscape, scientists weren't considered elitist and therefore capitalists and untrustworthy (although some of them are). I've spent a lot of time trying to tell people that "science" is a basic trait of being human. What happens when I try adding balsamic vinegar to the potatoes? (Blech) Which toys does the dog like best? (the plushy squeaky ones that are fun to destroy) As humans we are experimenting every day in little ways we don't even notice. I believe it's part of our creativity.

There's a good neuroscientific explanation for why people wouldn't want to eat straight salt. At low concentrations of salt, salty taste receptors are activated, but at high salt concentrations, bitter and sour taste receptors are also activated. (See https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11905 for some of the original research.) As far as I know, there's not a similar aversive effect for high concentrations of sugar.