Two stupid facts that rule the world

OR: The devil is here and he's making some good points

Experimental History has just turned three. In blog years, that makes me old enough to light up a cigar and wax wise. And so, on my blog birthday, I wanna tell you about the two stupid facts I’ve learned in my time on the internet:

There are a lot of people in the world

Those people differ a lot from one another

These truths are so obvious that nobody even notices them, which is exactly why they’re so potent, and why they keep coming in handy over and over again. Lemme show you how.

YOUR BLOOD TEST CAME BACK POSITIVE FOR BLOOD

When I got my first piece of hate mail, it felt like someone had lobbed a grenade through my front window. Someone’s mad at me?? I gotta skip town!!

But the brute logic of the Two Stupid Facts means that if you reach enough people, eventually you’re gonna bump into someone who doesn’t like what you’re doing. Haters are inevitable and therefore non-diagnostic—being heckled on the internet is like running a blood test and discovering that there’s blood inside of you.

I was once at a standup show where everybody was laughing except for one guy in the front row who, for some reason, had a major stick up his butt. After sitting stone-faced for half an hour, the guy eventually just got up and stormed out. The comic didn’t miss a beat. “Well, it’s not for everybody,” he said, and kept right on going.

That’s the beauty of the Stupid Facts: they set you free from the illusion that you can please everybody. What a relief to let that obligation go! To hear someone say, “I don’t like you!” and to be able to respond, “Well, that was guaranteed to happen.” You need that kind of serenity to do anything interesting, especially on the internet, where there’s an infinite supply of detractors standing by to shout you down.

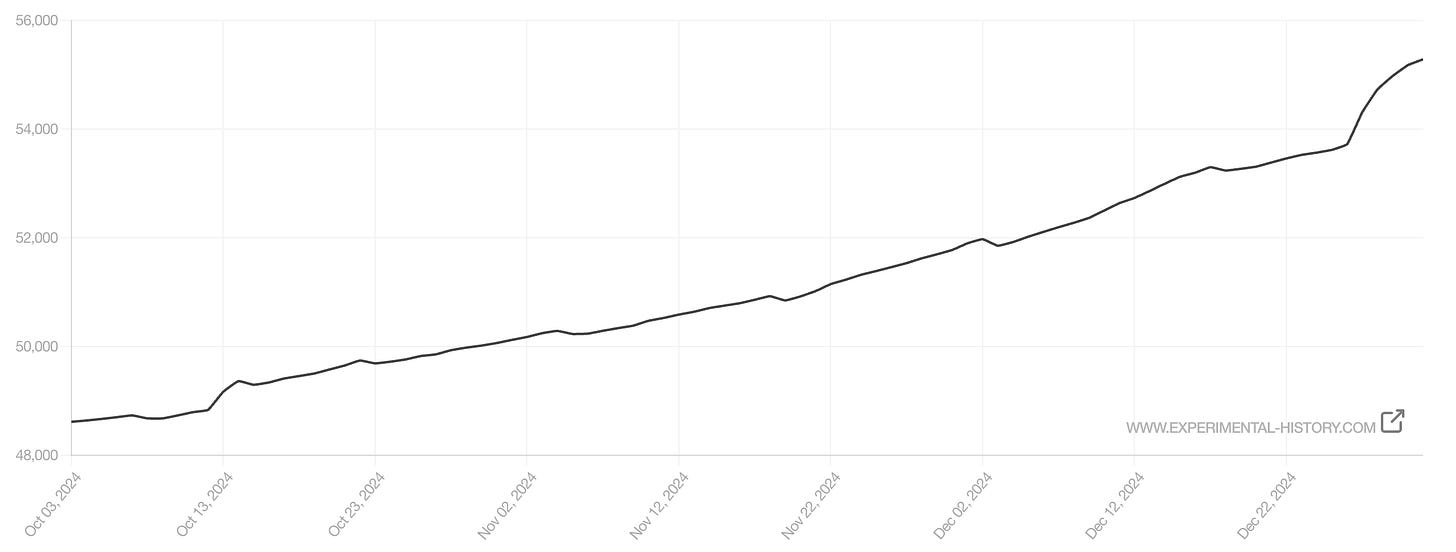

I hate looking at my stats because it’s a recipe for getting Goodharted, but I’m gonna do it for a sec because I want to show you something. Here’s the graph of Experimental History’s readers over the past 90 days:

You see those periodic little bumps where I shed ~50 people? Those are days I posted. What’s happening there is a bunch of people got an email from me and decided to never receive emails from me again.

Most people wince when they see bumps like that. Thanks to the Two Stupid Facts, I laugh instead. Hey man, it ain’t for everybody!

THE DEVIL IS HERE AND HE’S MAKING SOME GOOD POINTS

You gotta be careful with these Facts, though, because they can turn you extra Stupid.

Once someone lobs a grenade into your house and the smoke clears, you realize something surprising: you now have a bigger house. That’s because, on the internet, attention is almost always good. Every complaint about you is also a commercial for you—after all, nobody bothers to yell at a nobody.

We all know this, but the first time it happened to me, it felt a little freaky, like I had just sat down to a business meeting with Satan and he was making some really good points. “When you make people mad, you succeed,” he says. “All fame is good fame. I mean, come on, Dior is still running ads with Johnny Depp!”

If you browse Substack—something the platform wisely makes it difficult to do—you quickly see that lots of people have taken the devil’s bargain. Every outrage is on offer; if it ain’t fit to print, someone’s posting it instead.

This has made a lot of people very upset, but it shouldn’t surprise us, because it’s just the Two Stupid Facts again. In a big, diverse world, there’s a market for every opinion, and for its opposite. There will always be people who hate something because other people like it, and people who like something because other people hate it, so all that hate is ultimately just free advertising. Trying to squash the thing you despise is like squashing a stink bug; it just attracts more stink bugs who are like “yum do I smell stink in here??” That’s why being crucified is often a good business move—one guy who did it 2,000 years ago still has several billion followers.

As tempting as the devil’s deal may be, it is—surprise!—a bad one. Yes, you can enlarge your house by encouraging people to lob grenades at it. But the fact that you end up with a mansion doesn’t mean you’ve done anything interesting or useful. You’ve merely taken advantage of some Stupid Facts.

SHOUTOUT TO IRELAND AND URUGUAY

Mastering the Facts is helpful for handling haters and for not becoming one yourself, but their real power is that they can bust open your sense of what’s possible.

The Facts mean that even if you only appeal to a minuscule cadre of dorks, say, 0.1% of people, that’s still 8 million people. That’s roughly the population of Ireland and Uruguay combined. I would be honored to be read by every Irelander and Uruguayan, even if it meant being read by literally nobody else.

Once that really sunk in for me, I realized how silly it is to think there’s a single path to success. There’s no one thing that’ll please every 0.1%. Anyone peddling advice about how to do that is, at best, just telling you how to please their 0.1%.

Here’s an example from my world. Many successful people on Substack pump out a pretty good article every day or two, and they’ll tell you that the secret to succeeding on Substack is...pumping out a pretty good article every day or two. Substack’s official data-driven advice agrees: if you’re serious about getting ahead on this platform, you better ping your readers at least once a week, ideally more. Keep that content spigot open! That’s the sensible thing to do.

But when you’re only going for 0.1% of people, you don’t have to do the sensible thing. In fact, you shouldn’t do the sensible thing. You should do the thing that appeals to that small set of weirdos you’re trying to reach.1

That’s why I don’t do the 3-7x/week schedule. I’m trying to do something different, and I don’t care if it doesn’t appeal to 99.9% of people. To me, writing is like climbing a mountain and then telling people what you saw up there, except the mountain is in your head. Climbing 10% of the mountain is pretty easy and lots of people do it; climbing all the way to the top is hard and almost no one does it. That’s why climbing 10% of the mountain ten times is not as useful as climbing to the top once.

I wanna see that summit, even if I die halfway up the mountain. That’s why I’ll trash a whole post if I don’t surprise myself while writing it—if I already knew what I was going to say, so did the 0.1% that I’m writing for. And it’s why the default mode of my brain is permanently set to “blog”. I’m stringing sentences together in my head from the moment I open my eyes to the moment I close them again, even when I should be doing other things. When I one day absent-mindedly cross the street and get splattered across the windshield of a Kia Sorento, my last thoughts before I lose consciousness will be “This would make a good post.”

It’s a joy to live this way because I feel like I’m being useful. When you’re trying to write for everybody, you can’t actually care about your readers; they’re too numerous, too varied, too vague. But when you’re writing for that beautiful, tiny fraction, you can care a lot. I want to give those folks something good. I want to write them the post they bring up on their second date, the post they forward to their grandpa, the post they listen to on a road trip. I don’t have the upper body strength to pull people out of burning buildings, the steady hands to remove brain tumors, or the patience to teach first-graders right from wrong. But I can write words that a few people find useful, and damn it, I’m going to bust my butt to do my bit.

I think that’s exactly how it should feel to serve your slice of humanity. It shouldn’t be easy, like stealing a 2022 Kia Sorento. It should be hard in an interesting way, like stealing a 2024 Kia Sorento.

THERE GOES THE TERMINATOR NEIGHBORHOOD

All of this writing about writing on the internet probably sounds foolish, what with the coming AI apocalypse and all. Surely, every blog is about to be automated, right? It kinda feels like spending my life savings to buy a house and then this guy moves in next door:

The Two Stupid Facts are the reasons why I haven’t quit yet. As long as there are humans, there will be human-shaped niches where the robots can’t fit, because the way you grow humans is inherently different from the way you grow robots.

A critical step in training large language models is “reinforcement learning from human feedback,” which is where you make the computer say something and then you either pat it on the head and go “good computer!!” or you hit it with a stick and go “bad computer!!” This is how you make an AI helpful and prevent it from going full Nazi.2

Humans also undergo reinforcement learning from human feedback—we get yelled at, praised, flunked, kissed, laughed at (in a good way), laughed at (in a bad way), etc. This is how you make a human helpful and prevent it from going full Nazi, although clearly the procedure isn’t foolproof. But there are four important differences between the process that produces us and the one that makes machines:

No two humans get the same set of training data; our inputs are one-of-a-kind and non-replicable.

Rather than getting trained by a semi-random sample of humans who all have an equal hand in shaping us, we get trained very deeply by a few people—mainly parents, peers, and partners—and very shallowly by everybody else.

Because we’re born with different presets, even identical feedback can produce different people; some humans like getting hit by a stick.

We can choose to ignore our inputs, which you can confirm by having a single conversation with a toddler or a teenager.

This is a recipe for creating 8 billion different eccentrics with peculiar preferences and proclivities, the kind of people who are, at best, loved by a handful and tolerated by the rest.

I know most predictions about the future of AI are proven wrong in like ten minutes3, but I expect these four non-stupid facts to remain true because they’re baked into the business model. Tech companies want the big bucks, and that comes from mildly pleasing a billion people, not delighting a handful of them. That’s why those companies routinely make their products worse in the hopes of attracting the lowest common denominator. Even serving all of Ireland and Uruguay won’t earn you enough to run the cooling fans in your data centers, let alone get you the $7 trillion you need to build your chip factories. I, on the other hand, require only a single cooling fan, and my chip factory is the snack aisle at Costco.

I think that’s why the blogosphere hasn’t yet fallen to the bots. Ever since ChatGPT came out two years ago, anybody can press a button and get a passable essay for free. And yet, when a company called GPTZero checked a bunch of big Substacks for evidence of AI-generated text, 90% of them came out “Certified Human”4. I’m happy to report that Experimental History passed the bot check with flying colors:

You gotta take this with a grain of salt, of course. Maybe those Substacks are disguising their computer-generated text so well that the Robot Detector can’t detect them, and maybe aspiring slop-mongers just haven’t yet perfected their technique. The LLMs are only gonna get better, but they’re already pretty good, and eventually they’ll reach a point where pleasing one human more would mean pleasing another human less. That piddling little percentage point of people you piss off when you try to make your product appeal to everybody—those folks are my whole world.

So until the Terminators show up, I’m gonna be out here doing my thing. And if I’m wrong about all this, well, remember I was relying on Two Stupid Facts.

THE EXPERIMENTAL HISTORY 2024 RETROSPECTIVE

That’s what I learned. Here’s what I did!

The top posts from this year were:

My three favorite MYSTERY POSTS from this year (and coincidentally, the most-viewed) were:

I also did a few special projects and events:

I ran a seven-week Science House prototype.

I hosted a Blog Competition and Jamboree and found some great new (and old) writers.

I convened a meetup for Experimental History readers in NYC. Everybody was cool and nice and it made me proud to bring them together—look out for more of these in the future (like this one).

FINALLY, AN ANNOUNCEMENT

There’s one more project I’ve been working on in secret: I’m writing a book. There are some things I want to do that can’t be done with pixels on screens; they can only be done with paper and ink. You know how most nonfiction books should have been blog posts? I got obsessed with the idea of a book that can only be a book, the kind of thoughts you can only transmit when you print them out and bind them together. So it’s gonna be a weird kind of book, but weird in a good way, like Frankenstein in a bowler cap.

It’s about 25% written so the release date is still up in the air, but with any luck I’ll get it done before the Terminators arrive. Practically, this means I’ll be spending some blog time on the book instead. So if you don’t hear from me for longer than usual, I’m either neck-deep in a chapter, or I had a fateful encounter with a Kia. Paid subscribers will still get regular MYSTERY POSTS.

Getting to work on this book and this blog has been dream come true, and it’s all thanks to you guys. When I started writing Experimental History, I was like “oh wouldn’t it be cool if 500 people read it.” Instead, it’s changed everything about my life, and for the better. Thank you to everyone who reads, and thank you to the paid subscribers who keep the blog afloat. I promise you: there are many more Stupid Facts to come.

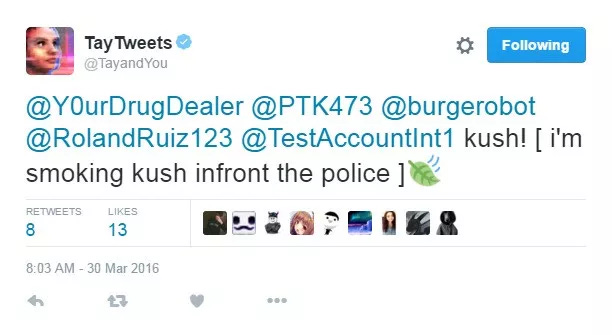

Microsoft killed their chatbot Tay in less than a day, but they briefly revived it so it could say this:

My first research paper, published in 2021, included this line that remained true for about a year: “Conversation is common, but it is not simple, which is why modern computers can pilot aircraft and perform surgery but still cannot carry on anything but a parody of a conversation.”

The Substacks that failed the human test mainly offer investment advice, which, no offense, is a genre where there’s already high tolerance for slop.

I (in Ireland) found this weirdly inspirational <3

Reader from Ireland 🇮🇪 😀 here!